Читать книгу Faces of Evil - Lois Gibson - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

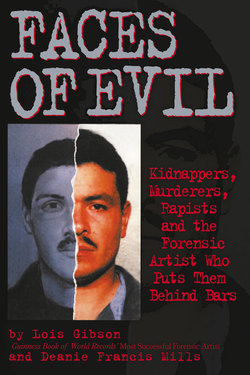

ОглавлениеPreface

People often ask me if I have nightmares.

They wonder how I can possibly sit through the constant parade of murderers, rapists, robbers, pedophiles and swindlers who march across my drawing board each day without being haunted by their faces in the depths of night.

Of course, I don’t just see evil faces. I also see the carnage their evil leaves behind, on the faces of their victims, in their eyes and on their bodies. Those of us who work in law enforcement often become what I call “secondary victims” of the violence we see each and every day of our lives.

And I see more than most.

As the only forensic artist for more than twenty-one years in one of the largest police forces in America—the Houston, Texas Police Department—I get the worst of cases—mutilations, murder, rape—an endless stream of misery that flows like tears through the various divisions of the department and pools at the door of my office.

Whereas a homicide detective may juggle three murder cases in a given week, I sometimes see that many in a day. I schedule them in with rapes, muggings, robberies and emergency cases that yank me out of bed in the middle of the night.

But when people ask me if I have nightmares, I say no. Not usually, anyway. The dead-eyed mug-shot stares of the killers and criminals whose faces I draw don’t stalk my dreams, because I know that, as the Apostle Paul put it, “faith is the evidence of things unseen.”

I’ve worked with the victims of those criminals and together we’ve taken something unseen—their tortured memories—and created evidence: a likeness of their attacker. I have faith, then, that law enforcement officers can take that likeness and use it to track down the bad guys. When they do, then I have empowered those victims and helped them to become something they never thought they would be: survivors.

Through my gifts and my labors, these survivors find, to their surprise, that they have been able to think what had been—up until then—the unthinkable and to take control of what had been uncontrollable. And when news comes that we’ve caught the bad guy, believe me, I sleep like the proverbial baby.

I haven’t just done my job; I’ve fulfilled my calling.

However, there is one aspect of my work that does haunt me sometimes, especially when the job involves a child.

Sometimes, I am called upon to help identify a murder victim.

And there’s only one way I can help with that task.

Many times, over the years, I’ve been asked to go down to the medical examiner’s office—which is just a euphemism for a morgue—and do a portrait of an unidentified murder victim. Over time, I’ve grown strong when asked to do this, because the way I see it, this is my way to help someone who can no longer speak or even cry out.

In many cases, I’ve learned that if the unidentified victim is an adult or a juvenile, then they were probably murdered by an enemy.

If that victim is a nameless child and none of the available databases turns up anyone missing who fits that general description, then most likely this child was killed by someone he or she loved, someone the child trusted to take care of him or her, someone who betrayed that trust. And when you see what has been done to the bodies during their brief, tormented little lives, then you know that death has often come as a relief.

They bring me photographs.

Big, strong detectives looking sad and depressed bring me color crime-scene photographs of tiny children they have found brutalized unto death and thrown out like so much trash on the side of the road, in a ditch or mud puddle or crammed in a dumpster. Sometimes the bodies have been exposed to the elements and it has become almost impossible to make out a face.

They bring me photographs. They ask if I can use the pictures as references, and transform them into a portrait of a child, smiling.

“If the victim’s smiling,” they say, “then maybe somebody, somewhere will recognize your portrait and help us figure out who this child is and who did this terrible thing to them.”

And so they bring me their grotesque crime-scene photographs and when it’s a child, well, I’ve never yet seen a detective who could hand them over without tears welling up.

You ask me if my job gives me nightmares.

The British poet, Dylan Thomas, wrote a poem after the horrors of the blitzkrieg bombing of London during World War II called “A Refusal to Mourn the Death, by Fire, of a Child in London.” In it, he eloquently told how overwrought outpourings of sentiment at such tragedies sometimes worked the opposite of what was intended, only cheapening the stark power of the event, which should stand alone.

Wordless, for there are no words.

He said, “After the first death, there is no other.”

I know what he means. Every time I hold in my hands a sacred photograph of the remains of another mangled little life and the sweet young voice cries out to me from dumpster or ditch or whatever else passes for a grave, then I know it is not the time for tears and mourning. Not yet.

“Never until...” writes Dylan Thomas, “...the still hour is come...Shall I pray the shadow of a sound...”

Never until the ghastly photograph in my hand has been transformed into a portrait of a smiling child on my drawing board and from there into someone’s heart, motivating them to go straight to their photo album, and from there to the police department... never until what’s left of a body becomes a once-breathing child who loved and was loved... never until then do I let myself mourn.

Never until then do I let myself weep.