Читать книгу Faces of Evil - Lois Gibson - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter One:

Angel Doe

I braced myself early one morning when a rookie homicide detective, Darcus Shorten, came to my office and asked if I could do a reconstruction of a little girl who had been found half-submerged in a watery ditch, her body wrapped in a blue fleece blanket decorated with happy little polar bears and reindeer.

Darcus, a young, vibrant African-American woman, had been teamed up on this case with Clarence Douglas, a seasoned veteran homicide investigator. Sergeant Douglas was the best partner a young detective could have. Kind and caring, with an intelligent, calm manner, he hadn’t let the cynicism of the job creep in over the years the way some police officers do. I knew he would never quit until this child could find her name and be laid to peaceful rest.

Still, I ached for Darcus, whose initiation into working on crime cases would be so gruesome. Some investigators go their entire careers without ever having to gaze upon the horrors she and Sgt. Douglas came upon in the ditch that day. It was a trial by fire, but I knew she was strong. She could and would handle it.

“Some kids found her,” Darcus told me. “And the patrol officers who responded to the scene figured she was about four years old, because she was so small. She only weighs forty-seven pounds and is less than four feet tall.”

“But?” I prompted, though I knew what Darcus was going to say.

“Clarence thinks she may be older than that, but that she was starved.”

“To death?” I asked.

“No.” She shook her head and I could see the weariness this job can give reflected in her young eyes. “Medical Examiner says she was hit in the head with something that probably caused her death,” she continued and after a short pause, added, “but you can tell from the bruises and cigarette burns and other old injuries all over her body that she suffered for a long time before she died.” Darcus struggled hard to blink back the tears.

“I’m sorry you have to face such a tough case so early in your career,” I said soberly. She nodded and left without saying another word.

I didn’t tear right into the envelope containing the hellish photographs. For a while, I busied myself with other tasks. They needed to be done, but mostly, I was working up my courage.

Ask any cop or emergency worker and they will all tell you that when it comes to child victims, it’s tough. Most of us have children of our own and it’s impossible to gaze at a murdered child without thinking of your own precious ones at home.

But we steel ourselves to do what has to be done.

After a few moments to collect myself, I reached for the envelope, pulled out the photos and looked at them.

I gasped. I’d never seen anything more horrible.

The child had lain, partially submerged in fetid water, her little face upturned to the elements, in the Houston heat and humidity, for more than two days. Animals and the ravages of exposure had peeled away the skin from her face. Her eyeballs were missing, as well as eyebrows. Most of her nose had been eaten off. Her lips were pulled back in a grotesque death-grin. Several of her front teeth were missing and her tongue protruded, swollen, from what remained of her lips.

From the black, curly hair on her head, the parts of her neck and head that had not been submerged in the water and what remained of the skin on her body, I could see that she was African American. From additional photographs taken at the autopsy, I could also see the starvation, the bruising, the burns... the torture.

It was so overwhelming that for a long moment, I feared that I would not be able to go on.

But I had to. She needed me. She was depending on me.

Numbly, I pinned the ghastly photos onto the right-hand side of my drawing board, which rests on my aluminum Stanrite 500 easel.

The human brain, I have learned, has a powerful ability to block out things it’s not prepared to handle. In some cases, this can be a blessed coping ability, but I knew I didn’t have that luxury. I have to be able not just to see the grisly scene set before me, but to look past it, so that I can create something beautiful out of something horrific.

I have to do it. They’re counting on me, those lost little souls.

And so are the detectives.

Through the years, I’ve developed certain techniques to enable me to handle the stresses and strains of my job. If I have to do a post-mortem drawing of an unidentified victim, especially one found exposed to the elements and particularly a child victim, then I turn on a television set and place the screen to my left as I face the paper with the gruesome photographs arranged to the right of it.

I try to find a compelling news program of some kind—not a tacky soap opera-esque talk show or one of those screaming cockfights between extreme points of view—but a reasoned, thought-provoking and informative debate on some issue or other that can hold my attention for at least a few minutes.

This serves as a distraction, a protection from the jarring emotional jolts that come with staring for a long time at faces brutalized beyond recognition.

I keep a small television set in my office. Normally in the mornings, even at home, I don’t watch television. I prefer to eat my simple breakfast of fruit and juice in peaceful silence while I gear myself up for the day’s stresses. (Just driving in Houston is stressful enough.) On that particular morning, I hadn’t even listened to the radio in the car. I’d plugged in a Diana Krall CD and listened to her sweet, mellow tones instead.

Now that I had pinned the photographs to my drawing board, I reached for the TV set as if I were treading water in heavy seas and it was a lifeline tossed to me from a boat. Positioning it to the left of my drawing board, I glanced at my desk calendar and watch to remind myself the day of the week and thereby remember what program might be on television at this time.

The date was Tuesday, September 11, 2001.

Everyone remembers where they were on 9-11 when they first heard the news, when they first saw the awful, terrible images over and over, the planes crashing into the Twin Towers in screaming fireballs, people running, bodies falling from the sky.

I was transfixed in horror, not believing what I was seeing. I wished I could look at the images without seeing them or otherwise somehow will them to go away, to stop, to turn back the clock, to make it not happen.

People were dying in front of my very eyes and there was nothing, nothing, nothing I could do about it. Like many other Americans and people the world over, I prayed. At least, as best I could, not even knowing how to pray about the things I was seeing or what to say, how to form words out of the unspeakable.

I stared at the massive horror unfolding on the TV screen until I couldn’t bear it any more. Then I forced myself to turn and face the smaller horror staring back at me from my drawing board.

This time, I wept.

As time passed, I sobbed awhile, prayed awhile, watched TV awhile, tried to concentrate on how I would do the sketch, watched some more TV, cried some more...

Then from a place so deep within me that it had no name, a still, small voice seemed to say, You can’t help them. You can pray for them, but you can’t help them. But you CAN help her. You can bring her back home. You can give her a name. You can help her restless little soul find peace.

It was a strange sort of comfort—for lack of a better word—that I just can’t explain. The unbearable images coming at me from the television screen somehow enabled me to bear the ghastly image pinned to my drawing board.

On that terrible day in September, I realized that I had to take the negative energy that was unleashed in me as I watched the violent attack on our citizens and use it as a force of good. I could take all the power and majesty of my own grief, fear, rage and horror and USE it. I could funnel it into the task before me.

And so I did.

Cried awhile, prayed awhile, tried to draw awhile.

While black plumes of smoke from the north and south towers of the World Trade Center billowed skyward and news anchors scrambled to their desks, I tore myself away from the sight and studied the photos of the little girl whose tiny life had been so violently snuffed out.

What I had to do was basically a skull reconstruction, because most of the flesh on her face had already rotted off due to water damage.

Steeling myself, I began.

I started, as always, from the top. This keeps me from smearing the pastel chalks with my hand as I lean on the paper. Usually, I do my sketches in warm black and white, but I knew that for purposes of identification, it would be better to use full color on my rendering of the little girl. With a black-and-white sketch, I can usually complete the job in an hour or so, but since this was a full-color reconstruction, with little to go on, it would most likely take me half a day.

That is, under normal circumstances. But 9-11 was anything but “normal.”

The top of the child’s head was relatively intact and I could see from the photographs that she had short, black hair, so I drew that. I knew I could go back later if I wanted and give it more of a style. The forehead was visible, so I was able to match the color of her skin as I worked my way down to her eyebrows.

Before I got very far, the phone rang. It was Dr. Baker, the medical examiner who had done the autopsy on the child.

In a kind, gentle voice, he said, “I know you don’t have much to work with there with those photos.”

“That’s true,” I agreed.

“Would you like me to get you something, er, better?” he asked. In a sad but determined voice he went on, “I could give you a prepared specimen.”

A prepared specimen is a nice way of saying that, in order to make my job easier, the good doctor was prepared to remove the child’s head and put it through a process known as maceration. This involves immersing the skull into a solution of 60% hydrogen peroxide. (What is used for household purposes is a 3% solution of hydrogen peroxide.)

This high content solution dissolves the soft tissue away, leaving the skull clean and intact. For an artist, this is an ideal way to depict the contours of that particular person’s face.

“It’s so kind of you to offer,” I said. “And you’re right; it would make my job easier. But I think I’d rather do this as quickly as possible, for one thing and for another, well, she’s such a tiny little girl. I’d really rather not this time.”

It was a form of respect for the body that he understood. I thanked him though, because I knew his offer was made with the sincerest form of kindness. He was trying to spare me having to go through what I was going through now: staring at what used to be a face, trying to draw it as it was in life.

I turned back to my task and glanced up at the television just in time to hear the horrifying news that a plane had crashed into the Pentagon. For a while, I watched the TV compulsively, hoping for some fragment of news that would somehow make sense of everything. The president released a statement that we were under attack by terrorists.

What could I do? I cried, I watched a while longer...and then, glancing back and forth from the horror on television to the horror on my drawing board, blotting my eyes with a tissue, I picked up my chalk and went back to work.

Eyebrows lie on top of the bones of the skull in a specific way and since I could see her superciliary arch (the brow ridge), I was able to place the little girl’s eyebrows just right. They would be fine, pre-pubescent hair and probably not very noticeable. Not much drawing, just some wispy child eyebrows.

The eyebrow follows the shape of the brow ridge. If people have a high, distinct arch to their eyebrows, it means that the bone is rather thick and takes a sharp curve as it travels downward. As I looked closely I saw this child had a small bone with a shallow curve.

Just as I was about to start drawing the eyes, Two World Trade Center, the North Tower, suddenly collapsed. It was… horrible? Terrifying? Mesmerizing? I searched in vain for words to describe what I was viewing.

There just weren’t words to explain what I saw as I stared, transfixed, helpless, and watched people die. The grief, which I realized all who watched felt, was speechless, unspeakable. Heedless of the chalk I was holding, I clapped my hand over my mouth, cried, “No, no, no,” and sobbed.

For a long time, I could not work. My eyes were too blurred with tears; I couldn’t even see what I was doing.

I was still sitting, the chalk in my limp hand, when the South Tower collapsed.

Bawling, blowing my nose, praying, trying to compose myself, a few minutes later I heard the report about yet another plane that had crashed in rural Pennsylvania, southeast of Pittsburgh.

“The world has gone mad,” I whispered.

For a long time, I was hypnotized by the images on television, but eventually, when reporters began repeating themselves and it was clear that nobody really knew anything new, I took a deep shuddering breath and turned my attention back to the little lost child whose image I was trying to capture.

The eyes of a person have specific places that attach to the inner corners of the eye socket. Since the flesh had decomposed and disappeared and the eyeballs were gone, I could clearly see the “landmarks” that told me how wide-spaced her eyes would be. The fold above the lid would be smooth and dark, since there would be almost no fat in the pad behind and the eyelids would be visible. (Lack of body fat lets that nictitating membrane curve over the eyeball.) So I drew tiny eyelids.

Meanwhile, it seemed as if our whole country was under attack and nobody knew where these evil monsters would strike next. I even glanced out my office window, picking out taller buildings, trying to assess if my own was at risk.

Then I scoffed at my own nervousness and went back to work, back to crying, back to praying, back to watching the TV, spellbound, like everyone else.

In police work, there is a peculiar phenomenon that occurs whenever there is a child murder, especially one so gruesome and emotionally wrenching as this one. When the detectives who “catch” the case “make the scene,” meaning, they go to the crime scene before the body is removed and begin their investigation, other police personnel slowly begin to show up at the scene.

They may be office workers, supervisors and so on. What they are doing is offering mute moral support, quiet, steadfast presence. In many ways, it’s like a silent memorial to honor this most innocent of victims.

But I wasn’t at a crime scene. I was alone in my office, coping with the horrors both without and within.

The phone rang again. This time I recognized the voice of homicide Lieutenant Steve Arrington and I knew instinctively that he wasn’t trying to intrude or check up on me or bother me.

He was hurting as badly as I was at what we were seeing happen to our country and to the tiny girl.

“Are you all right?” he asked. “Can you still work despite the horror of what’s going on in our country?”

I assured him that despite my own shock I was working.

“Lois, can you make her smile, like when she was alive?” he asked, a bit embarrassed at making such a request at this moment.

He knew and I knew that I could. The phone call wasn’t really about that and we both knew it, but I was so grateful for his support. “Sure I can,” I said softly.

“Make her pretty,” he said quietly, “like I know she was in life.”

“I will,” I said.

“I know you will,” he said. “I know you can. Help us find her, help us nail whoever did this to her and pray for our country.”

I promised that I would and we hung up. I felt as if I had been hugged. It gave me strength.

Once again, I went back to work.

In order to tell how to draw the “iris to eye opening” ratio right, I glanced at photographs I had in my office of my two children, Brent and Tiffany. They were teenagers now, but I had some pictures from when they were small children that I used as references. The iris, I found, would occupy more of the eye opening than it would in an adult, but less than in an infant. I worked out a good balance and gave the little girl nice eyelashes.

Her ravaged little face was beginning to come to life. It gave me hope. While the somber television news anchors tried to sort out what was going on in our country, I listened and kept working.

The nose, I decided, would be smooth. The bridge that I could see from the crime scene photographs was smooth and lay low to the facial plane. The outer edges of the bottom part of the nose would start about one-half to two millimeters outside of the nasal hole, which was visible through the last film of flesh that hadn’t dissolved in the water. I gave her average-sized nostril holes.

The cheeks were easy. I covered those bones with the appropriate muscles and the smooth, brown, little girl skin.

It was time to draw her smile. Her alveolar ridge—the bony arch from which the teeth protrude—was wide as I faced her, so I drew it that way. The bottom teeth were arched so wide that I felt certain she would show them along with the top teeth when she smiled, so I drew the bottom teeth just above the full bottom lip as they would appear during a happy grin.

Of course, one thing an artist has to do at this point is depict the tongue peeking through as the light hits it, along with a glistening shine, because a live person’s mouth is always wet.

The little girl was missing one tooth and the other was tilted. I needed to know a strong estimation of this child’s true age. Height and weight would not tell the true story.

So I put in a call to the forensic dentist, Dr. DeLattre, who had examined the body.

Dr. DeLattre said, “Her front teeth were all adult teeth but the back teeth were deciduous or baby teeth.”

That told me two things. One, this child was six or seven years old, not four, as Darcus had said the officers who found the dead child thought, due to her tiny, shrunken size. And two, she had not lost that front tooth naturally. It had been punched out and during the same incident, the tooth next to it had been jammed up back into the socket in a crooked way.

This was a sickening development that caught me by surprise. I’d assumed...well, it just hadn’t occurred to me that this precious child had been punched in the mouth.

I asked, “How long before she died do you think that tooth was knocked out?” Dentists can tell by how much the bone has grown shut after tooth loss.

Her voice sad, she said, “About six weeks to two months.”

Poor, sweet baby.

I decided to use the lost tooth as a sort of “gap-toothed grin” when I sketched her smile. I made her as pretty as Arrington had asked and I thought she once had been as I reflected on how much she’d been through.

After completing her smile and drawing the chin, I sat for a moment and stared at the blue plaid shirt she was wearing. It was only visible at a distance from the shot where she lay on the red plastic body bag on which she’d been placed by personnel from the medical examiner’s office. I tried to reproduce it as closely as possible, because it was another clue to her identity.

Finally, I put some shadows on her neck under her chin and fluffed up her hair a bit, as if it had just been washed.

My sunny, windowed office is located on the seventh floor of the Travis building. Ironically, this houses the Robbery division of the Houston Police Department. Robbery detectives seldom see the kinds of violence I have to deal with all the time. Their work is usually not as emotionally wrenching as it can be for homicide detectives or those who work in Juvenile Sex Crimes. Sometimes the detectives are surprised at the dreadful things I often have to deal with and even on this frightening day in which there were so many horrible sights, as I worked, some of the detectives drifted by and commiserated on the shock and horror affecting our country and the shock and horror of the photographs pinned to my board.

One of the detectives said something I’ll never forget. “They’ve checked all the area schools, looking for a child who has been missing from class and is unaccounted for or who would otherwise fit her description,” he said. (In Houston, school starts in August, so a child absent for several days this far into the semester would be noticed.) “She’s not been reported missing by a single school.”

I looked up at him, as he leaned against the doorjamb of my office.

“You know what that means,” he added.

Yes, I did know.

“It means that she has been deliberately kept out of school by somebody,” he said. “She’s been locked up someplace, hidden away.”

Over the drawing board, our glances met.

“She’s a closet child,” he said.

They called her Angel Doe.

Police investigators searched databases for similar cases nationwide. In Kansas a little black girl near the same age had been found beheaded and discarded about four months before Angel Doe turned up in Houston.

Though investigators didn’t find any connection, I found one difference truly heartbreaking. Kansas City police had been inundated with more than 800 leads when they first started investigating their own case. There had been a tremendous public outcry and a candlelight vigil.

But when poor Angel Doe was discovered in Houston, the entire country was reeling from the horrendous national tragedy of September 11. News outlets were dominated by that story and consequently, an unidentified little black girl found in a ditch full of water and old tires in southeast Houston drew little attention.

Not for lack of trying—Sgt. Douglas and Officer Shorten did everything in their power to keep the story alive and copies of my sketch displayed (what Officer Shorten called “foot-work,” just walking through the neighborhood, posting copies of my sketch with pertinent information), but in those early weeks, they had little response.

An Internet search turned up several possible leads; another one in Kansas, one in North Carolina and one in Houston, but none panned out.

Houston’s Child Protective Services caseworkers combed their files and the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children entered Angel Doe into their database... all to no avail.

Jerry Nance, a caseworker for the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, was quoted in the Houston Chronicle, “Facial identification is the only thing that will solve this case,” adding, “A child that young doesn’t have fingerprints, a driver’s license or DNA on file.”

The detectives felt terrible about all this and I felt as badly as they did. By this time, we all had an emotional investment in this case. The way Sgt. Douglas put it was, “This case is deeply imbedded.” He meant, in our souls.

“Not knowing who she is has really been trying to me personally,” Officer Shorten said. It bothered her deeply that the police could not put a name to this child. She even pinned a copy of my composite drawing on the bulletin board behind her desk.

Sergeant Douglas wanted, more than anything, to identify Angel Doe and give her a decent burial before Christmas, but as time passed with no new leads on the case, it was looking unlikely.

In Kansas, concerned citizens paid for a funeral and buried their little nameless child. They had been searching for her identity for seven months and they wanted at least to give the tiny child a proper burial.

Slowly, the country began to recover from the initial shock and horror generated by the events of 9-11. Rescue efforts evolved into body recovery. Our national grief was nowhere near healed yet. But as New York firefighters, police and steel workers—and, down in Washington, D.C., soldiers and firefighters—combed through smoking wreckage for the remains of the lost, the rest of us slowly returned to the vestiges of our normal lives, even as we knew that things would never be quite the same again.

A somber Christmas came and went.

Houston never has much of a winter and the days began warming up. In early March, local and regional events once again began to creep into city newspaper and evening news headlines. In that period, Sgt. Douglas and Officer Shorten renewed their efforts to publicize Angel Doe’s case.

A police spokesperson released a statement to newspapers: “The worst part is that no one has come up to say this child is missing. No parents or friends or relatives,” he said. “It’s as if she never existed.”

That week, police, assisted by Crimestoppers Child Watch of North America volunteers and other civic leaders, printed up numerous flyers with my sketch on it and posted them throughout the neighborhood where Angel Doe’s body had been found. They released a photograph of the blue blanket that had been used to wrap her body. They held news conferences and redistributed my sketch to news outlets, patiently answering repeat questions, doing all they could to get the word out.

I felt as frustrated as they did.

“How will this case get solved?” I asked Clarence.

“A grandmother will have to call it in,” he said. “It will have to be a grandmother who solves this case.”

He was right.

It was the child’s grandmother, Alice Curtis, who finally recognized my sketch. Alice says that she does not watch television other than religious programming and (we can only assume) does not read the newspaper. This is how she explains the fact that, although my composite sketch of her granddaughter LaShondra was televised and printed in the paper, off and on, for six months, she did not see the sketch.

When detectives held the press conference in early March of 2002 and, once again, displayed my composite drawing of “Angel Doe,” Alice says that day she was “flipping channels” when she came across the news conference. She says she “knew right away” that it was her granddaughter.

She called the police. “That’s my child,” she told Sgt. Douglas. He says she insisted on meeting with him that very night; he could not convince her to wait until morning. After several extensive interviews with Alice and two of her other grown daughters, Sgt. Douglas believed they had finally identified Angel Doe.

Although prosecutors would refer to her as “nobody’s child,” this was not really the case with LaShondra.

To my way of thinking, a “nobody’s child” is one who is never loved and is shunted around from foster home to foster home until he or she either winds up in juvenile lock-up, becomes a streetwise runaway or turns up dead at the hands of a drug dealer or pimp or suffers some other tragic fate. It’s deeply depressing to me when I think how many, many children fit that description in this, the richest country in the world.

Although LaShondra’s brief little life started out tough, she was not unwanted. She was born to a crack-addicted mother who already had four other children. Though the infant was treated for drug addiction at birth and put into foster care as a newborn, her grandmother, Alice Curtis, wanted to raise the child. Once Child Protective Services decided that LaShondra would have a good home with her grandmother, Alice took custody of the baby. LaShondra’s birth mother, Connie Knight, did not object.

LaShondra was a jolly, bright baby who was the light of Alice and her husband Roger’s lives.

“She was the kind of child, you could not help but love her,” Alice told a newspaper reporter later. But when LaShondra was just a year old, Alice had a sudden stroke that rendered her incapable of taking care of an infant.

Still, LaShondra had family who cared. Living in another state was one of Alice’s sons and his wife. They did not have any children of their own and gladly took the baby into their home.

When Clarence and I spoke of these things later, he always had to blink back tears. “She never wanted for anything there,” he kept saying. Her new parents adored her and LaShondra began calling them Mommy and Daddy. The child, who was known to be bubbly and sweet, thrived.

But back in Texas, three years after LaShondra’s birth, Connie claimed to be drug-free and she began to pressure her mother to let her have her daughter back. She started calling her brother and sister-in-law frequently, demanding that they allow her to take LaShondra. She even called local police where the couple lived, claiming that they had stolen her baby. Finally, when it was time for LaShondra to start school, her grandmother offered to take her back and the couple reluctantly agreed.

But it wasn’t Alice who came to pick up the child. It was Connie.

Since Alice Curtis had custody of LaShondra and since she did not object, there was nothing the heartbroken couple could do, legally, to keep the little girl. Alice Curtis never notified Child Protective Services of her decision to allow Connie to take LaShondra back. If she had, CPS caseworkers would have visited the home, made reports as to the condition of the child and evaluated her new home. But they never knew.

Time and time again, I have seen cases where unworthy, uncaring parents demand the return of their children and I don’t believe it has anything to do with love. Some people regard their children as possessions and often don’t rest until that “thing” has been returned to them. Whatever Connie Knight’s motives for yanking LaShondra away from the home she loved and dragging her back to Texas, one thing is certain: from that moment on, LaShondra’s life became a living, bloody hell.

Soon, she disappeared from sight.

Alice Curtis claims she phoned her daughter frequently, asking to speak to LaShondra, and visited the house. Apparently, she was easily manipulated by the former drug addict, who convinced her elderly mother, time and again, that LaShondra was out of the house, staying off and on with a distant relative of her stepfather’s.

When Alice became naggingly persistent, Connie allowed her to speak with LaShondra—briefly—on the phone. “I never got any signals anything was abnormal,” Alice said later.

What the old woman didn’t realize at the time was that she wasn’t speaking to LaShondra at all. Connie had put up one of her other daughters to pretend to be LaShondra whenever her grandmother called.

“I never got alarmed, because I saw the other children and they were fine,” Alice said.

Yes...the other children. What about the other children?

In the June 30, 2002 Houston Chronicle, Dr. Curtis Mooney, president of DePelchin Children’s Center, which provides counseling for children and families in the Houston area, including those suffering abuse, stated that it is not unusual for a parent or parents to pick one child out of a family to use as the family’s “scapegoat,” which means that child will suffer more serious consequences for misbehaving—even being locked up.

“That child becomes the one everything is blamed on...Such a victim can be targeted because he or she is seen as a ‘problem child,’ or perhaps has a more aggressive personality than the other children,” said Mooney.

Whenever Alice called Connie and asked why LaShondra wasn’t there, Connie would always tell her mother that the little girl was uncontrollable and that other relatives had better luck with her, saying, “She has mental problems.”

It’s hard not to judge Alice Curtis. Most of us who have children feel, when months and months have gone by without a sign of a grandchild who was supposed to be living only a couple of blocks away, that we would be hugely concerned, we would do something—especially if we knew that this same child’s mother had had drug addiction problems in the past.

But Alice, whose health was not good, was caring for her own dying mother during those days. Distracted, unwell and manipulated by her daughter, she let herself believe that LaShondra was being taken care of somewhere by someone who loved her.

As I said, the human brain is capable of blocking out things it’s not prepared to handle.

Even so, a mother’s instincts can be a powerful thing. Alice claims that, around the first week of September, 2001, she became almost frantic to find LaShondra. When she insisted on seeing the little girl, Connie told her that she’d put LaShondra into a psychiatric facility. Alice demanded to visit LaShondra and Connie agreed.

But on the day they were supposed to visit the facility, Alice pounded on Connie’s door and found the house completely empty.

The family—Connie Knight, her common-law husband, Raymond Jefferson, Jr. and her children—had fled in the night. No one in the family had heard from them. No one knew where they were. At that point, Alice’s own mother passed away and she didn’t have time to worry about a daughter who tended to pick up and leave whenever things got too hot for her.

Using Jefferson’s employment records, Sgt. Douglas traced the family to Louisiana, where they had been living since LaShondra’s death.

All three of the surviving children, ages four, thirteen and sixteen, who lived in the home with Connie and Raymond, denied ever even having seen LaShondra. When Sgt. Douglas showed a photograph of LaShondra in happier days to the thirteen-year-old, she started to shake—violently—from head to foot, but maintained that she had not seen LaShondra. The children each swore, adamantly, that they did not even have a sister.

Raymond swore he didn’t even know the girl and for several hours, Connie maintained LaShondra was still in Georgia with relatives.

So Sgt. Douglas showed them Jefferson’s employment records, in which he’d claimed LaShondra as a dependent, and witness statements from Houston neighbors that there had been “another child” who was not allowed outdoors. He showed them photographs of the blue fleece blanket and he showed them photographs of the closet from their house in Houston, the one with human feces smeared on the walls and floor.

Finally, Connie cracked. At first, she confessed that she had been responsible for LaShondra’s death and she was arrested. The children became hysterical and refused to speak, not to police, not to social workers, not to counselors, not to anyone. In his calm, reassuring way, Sgt. Douglas left word that, when they were ready to talk, he was ready to listen.

After several weeks, Sgt. Douglas’s patience was rewarded. He was contacted by family members who told him that the girls were finally ready to talk. They admitted that, although both parents had been horribly abusive to their sister, it had been Raymond who had killed her.

Confronted with her children’s truth-telling, Connie changed her story. Although he continued to deny even knowing LaShondra, ultimately, Raymond Jefferson, Jr. was charged with injury to a child, failure to stop her mother from abusing her and denying her proper medical attention. Connie was also charged with injury to a child. They were both jailed in Harris County.

Family members, filled with shame, rage, guilt and grief, buried the tiny girl, giving her, at long last, the funeral that Clarence Douglas and Darcus Shorten had so longed for. The detectives attended the service. On the funeral program, above a smiling and happy picture of a younger LaShondra, were printed the words from the Twenty-third Psalm: “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil...”

Weeping relatives said a few words about how LaShondra had to die because “God needed another flower in His garden.”

But little “Angel Doe” did not have to die; nobody should ever have to die the way she did.

The rest of the story, when Clarence and Darcus finally pieced it all together, was grim.

Because she’d been ripped from the only home she’d ever really known, where she was loved, and thrown into a house full of strangers thousands of miles away, LaShondra did not behave like the adoring daughter her mother and Raymond thought she should be.

So they threw the little girl in a closet.

And left her there.

She was not permitted to leave the closet to go to the bathroom, but when she soiled herself or used the closet floor, she was terribly, horribly punished. And she was starved by her morbidly obese mother.

The other children were told that LaShondra was “crazy” and to leave her alone, but at night or when her parents were out of the house, the thirteen-year-old daughter would sneak LaShondra out of the closet and feed her or creep past and throw parts of her own meals into the closet—LaShondra’s only food.

Sometimes the girl slipped her brother’s training potty into the closet to help out her sister. On cold nights, she let LaShondra slide in under the covers and sleep with her, but they had to hurry her into the closet very early the next morning, because if Connie found them out, she would beat LaShondra.

LaShondra was never enrolled in school. She was not allowed outdoors. She was repeatedly hit, kicked and burned with cigarettes by both her parents.

When LaShondra’s sister asked her mother why LaShondra had to stay in the closet, Connie only said, “Because she doesn’t know how to act,” or, “because that’s where I want her to stay.”

All the children were forced to keep the secret from their grandmother.

On the night of September 7, 2001, little LaShondra said or did something that Raymond didn’t like and he kicked her so hard that she fell back onto the heater, cracking her skull, and began “to shake all over,” said the sisters in trial testimony. Raymond went to the store and brought back some ice, but nothing helped. Finally, he and Connie told the children that they were taking LaShondra to the hospital.

When their sister did not return, Raymond ordered the children never to speak her name again or “I’ll take you to the same place I took her.”

During her testimony at the trial, the closest sister suddenly put her face in her hands, threw back her head and keened with grief so wrenching that District Judge Mary Lou Keel stopped the proceedings.

In a dull monotone, Connie testified that Raymond made her drive him and the blanket-wrapped child to a secluded spot. While she waited in the car, he took the little girl into his arms and walked some distance from the car. “Then,” Connie testified, “I heard a splash.”

Other than that, the only other things she would say on the stand were, “I don’t know,” or “I don’t remember.”

In an agonizing jury deadlock, the first trial of Raymond Jefferson was declared a mistrial. Eleven of the jurors wanted to convict him, but one was not entirely convinced that Connie had not killed the child herself, as she originally claimed.

But prosecutors Casey O’Brien and Sylvia Escobedo would not be deterred. Within a few weeks, they mounted a second trial.

After all we’d been through with our little Angel Doe, I couldn’t stand not being there myself this time. When a witness canceled a composite sketch appointment and rescheduled it for later, I grabbed my purse and headed for the courthouse.

At the trial’s final proceedings, as I sat in the spectator gallery, I could see Raymond Jefferson in profile and I studied him. He was a big man, six feet tall and weighing more than 200 pounds. He had fists like cement blocks. I kept thinking about what those brutal fists had done to that child’s face and it was all I could do not to throw up.

But his face? His face was bland.

The thing is, when you see a monster like him in court, you expect him to look, well, like a monster.

But they never do.

The prosecutors were rewarded for their determination and I was quietly pleased when this trial resulted in a conviction for Raymond Jefferson, Jr. It took that jury less than three hours to pronounce justice for little LaShondra.

On August 22, 2003, LaShondra’s stepfather was given the maximum sentence—life in prison. (As of this writing, his attorneys have filed an appeal with the Fourteenth Court of Appeals.) He will be eligible for parole in 2018, when he is sixty-five years old. Connie Gazette Knight pled guilty and was sentenced to fifty years in prison.

Later, I asked Clarence whether Connie herself might have been a victim of Raymond’s abuse, which could have contributed to her own abuse of her daughter.

Solemnly, he shook his head. “Connie Knight would never put up with any abuse from anybody,” he said firmly. “She’s plenty big enough to take care of herself,” and added, “No...The truth is, she’s just plain mean.”

A few months before Officer Shorten brought me the death photos of little LaShondra, I read a Newsweek cover story in the May 21, 2001 issue on the nature of evil. In it, psychologist Michael Flynn of York College in New York was quoted, “I spent eighteen years working with people who everyone would call evil—child molesters, murderers—and with a few exceptions, I was always struck by their ordinariness.”

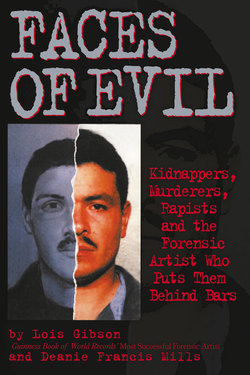

I know what he means. If you want to know what the face of evil looks like, well, it looks like your neighbor, or your boss, or your lover.

I know, because I’ve drawn more than three thousand evil faces and most of them did not “look” evil. When I see them in court, these murderers and rapists, they always have what I call a “shark-eyed look.”

Just blank. Like they’re there and yet not there.

At least, that’s when they’re in court or standing in front of a mug-shot camera. But when they’re in the process of raping and murdering, that bland expression can change dramatically.

I know, because I’ve seen it for myself. I’ve looked right into the eyes of a man who was trying to kill me and I know what the face of evil really looks like—right then—not later, all cleaned up for court.

I know what it means to feel like a helpless victim, to feel caged in the terror and powerlessness of one day, one moment that can change you forever, an endless, heart-stopping moment when you are fighting for your life, sense it draining out of you as you choke for breath... when the world goes dark and you’re all alone... facing evil.