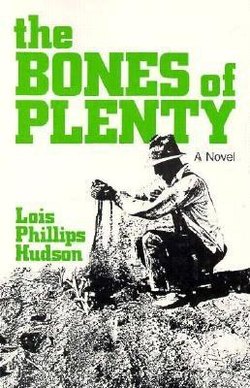

Читать книгу The Bones of Plenty - Lois Phillips Hudson - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Saturday, March 4

ОглавлениеThe drifts of the blizzard around the steps of the Eureka Bank were all undisturbed, so that it could as well have been tenantless for two years as two weeks. But not even having every other bank in the nation for company could make it look less lonely.

The President had closed them all. Harry Goodman’s Eureka Bank—assets $78,000, liabilities undetermined—was no more tightly closed than the biggest, oldest bank in New York. On that day the Eureka Bank was no more of a failure than any of the others with their good and bad mortgages and other kinds of good and bad paper.

The President’s inaugural address came over Herman’s radio in the forenoon, and the store was filled with men who had come to hear it. Some of the men had radios at home, but they came to Herman’s store anyway, so as to have company while they listened. Even George was there, standing far back against the shelves, not joining the men around the stove or the ones who leaned on the counter, hovering over the radio, so possessed by the voice in it that they forgot themselves and let their hopefulness and their anxiety show in their faces. George, standing apart from them all, ground his teeth and wondered how they could be so taken in. He didn’t like the phony accent and he didn’t like the highfalutin language and it was just too much when the President said, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” By God, what rich man was going to accuse him of being afraid and get away with it, anyhow? He hardly heard any of the rest of the speech, he was so angry at being called afraid.

When the speech was over and the first murmurs began, he said loudly, “I’d like to get that hothouse pansy out on a farm for just one hour. I’d like to watch him pitch bundles into a thrashing machine when it’s around a hundred and ten in the shade—or wrastle a bull calf that’s taken a notion he just don’t want to grow up to be a steer!”

Zack Hoefener began to laugh, holding his goiter with his hand, as though he must not lose track of the upsetting vibrations of his laughter and his heart beating there. Otto Wilkes laughed too, and so did Wally Esskew and Lester Zimmerman. Even the Koslovs began to laugh, though George doubted that any of them could understand what was funny about giving a man with that accent the chore of emasculating a calf.

Clarence Egger, whose arm had been gobbled up by a threshing machine, waited for them all to stop. “Don’t you sheep brains know that the guy can’t even walk? He had infantile paralysis, for Christ’s sake!”

George was not going to be made a fool of by Clarence Egger. “Well, he got a great big infantile silver spoon, too, didn’t he?”

“I’ll take walking any day,” Clarence said. He was the only man in the room who dared, because his right arm was gone, to stand up to George. At times when he was drunk enough, Zack would do it, but nobody else ever did.

Nevertheless, George felt that they were displeased with him for making them laugh at a crippled man. God-damn them—they were so dumb and ignorant—always confusing the issue. The issue was that a rich man was telling them all not to worry even if they had just lost their last red cent to a little Jew banker. A rich man who couldn’t possibly imagine what it was like to work sixteen hours a day for six months of the year and to sit in a dark house smothering in snow for the other six months, wondering where the money for coal was going to come from. That was the man who was telling them not to worry, and that man’s coddled, polished ignorance was the issue—not whether or not the man could walk.

George considered himself a well-spoken man, but he had no words to substitute for the obscenities he wanted to say to these silly bleating sheep. Clarence Egger calling him a sheep brain. He put his hands on his hips and lifted his shoulders as though he would sashay into a wrathful jig and he roared the chorus of a bitter song —

Oh, Lady, would you be kind enough to give me a bite to eat —

A piece of bread and butter and a ten-foot slice of meat?

A cake, a pie, a pudding, to tickle my appetite —

Let them see, if they could, that this was their song unless things were radically changed. He shoved his way past them as he sang, and stamped out the door. He went on singing as he took the blankets off the horses and climbed on to the seat in the wagon box —

Come all ye jolly jokers, and listen while I hum.

A story I’ll relate to you of the Great American Bum.

From North to East, from South to West,

Like a swarm of bees they come.

They wear a shirt that’s dirty

And full of fleas and crumbs.

I’ve met with all the toughest cops—as tough as they can be.

And I’ve been in every calaboose in this land of liberty.