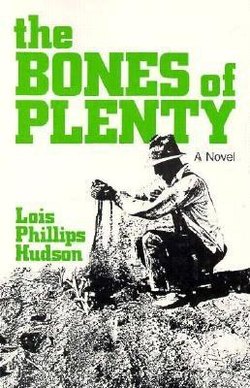

Читать книгу The Bones of Plenty - Lois Phillips Hudson - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Preface

ОглавлениеIn his introduction to Facing West: The Metaphysics of Indian-Hating and Empire-Building (1980), Richard Drinnon remarks, “The record of history is nearly barren of authentically novel responses to novel circumstances.” If I can be forgiven for beginning this preface to a new edition of The Bones of Plenty with a pun, I will say that the tragic fact he states so succinctly does, indeed, constitute a major impetus for the writing of many novels, including this one. No matter how many absurd repetitions of human folly and political cynicism I have been obliged to observe, I still cannot bring myself to shrug my shoulders and say, “The more things change, the more they are the same.” George Steiner recently wrote, “It is one of the responsibilities of the novel to chronicle small desolations. These are sold short in that harsh artifice of selective recall we set down as history.”

This novel tells a story that had to be told, and I was the only one who could tell it. (These, I believe, are the only two reasons a serious writer writes.) This book tells of the “small desolations” which the history of the Great Depression records only as statistics. President Roosevelt’s New Deal was far from being an “authentically novel response” to the crisis in which millions of men, women, and children suffered desolations that profoundly scarred their lives, if, indeed those lives were not utterly ruined. Perhaps a truly novel response fifty years ago might have prevented the current repetition of so many of the events I describe in this book. Again we have desperate pleas for moratoriums on farm loans and mortgages, we have farmers organizing to stop sheriffs’ auctions, and we have thousands of farmers going bankrupt, despite all the government subsidies which, in a very un-novel way, usually seem to help most the rich and powerful. As I write, an eighteen-year-old Minnesota farmer’s son has just been convicted of shooting and killing two bank officials who were seeking to sell the family farm, which they had already repossessed. Bruce Rubenstein, writing about the case in the Twin Cities’ City Pages (May 2, 1984), describes for us how things have not changed—except to get worse:

If ever an isolated event [a small desolation] served to illuminate a much larger situation, then this was it. In 1977 suicides in rural Minnesota hit an all time high—227—and they’ve stayed high since.… In 1982 a record number of farms, over 5000, were put up for sale in Minnesota.… Twenty-five percent of U.S. farms market over 80 percent of all agricultural products sold. The last 65 years have seen the relentless replacement of the family farm by the huge, technologized farm.… In 1920 there were five million farms in the United States. Today, with roughly the same acreage under cultivation, there are less than two million farms.… The local lender,… the unwitting tool of Wall Street,… has always made a handy target for the farmers’ frustrations.… The situation of the small dairy farmer like James Jenkins provides striking evidence that American agriculture is a rigged game.

A critic has said of Maupassant that he wrote out of anger at the difference between the way things are and the way they ought to be. I hope no reader will be able to read this book without feeling some of that anger, and without feeling led to ponder the tendency, apparently so deep in most of us, to try to fix a problem by doing more of what got us into the difficulty in the first place, as Drinnon painfully observes. The ultimate illustration of this tendency—our attempt to solve our nuclear weapons dilemma by building more and more nuclear weapons—must not blind us to the many other examples of that unimaginative conservatism to which the writers of novels so frequently try to draw our attention.

Today we see one frightening example in these very fields which, fifty years ago, seemed about to blow away in clouds falling into the Atlantic, clouds so heavy with precious topsoil that New York City needed street lights at noon. We are now caught in a vicious circle in the production of our daily bread (and all our other food) which begins in these fields and embraces not only their problems but many others as well, in such areas as transportation and marketing. The genesis of this circle is, in large part, an economic system that seems no closer to addressing the necessities of saving our planet and equitably distributing its fruits than that system was fifty years ago. As the economic system dictates that farms must become larger and larger, worked by larger and more costly machinery, we begin to see the breakdown of the soil itself. In many of our richest areas, the soil has become ever more compacted under so much weight, so that the machines we used to work the land fifteen or twenty years ago can no longer plow deeply enough. A novel response is surely needed at this juncture, but so far ours seems to consist of making even huger models of the same machines.

Then we compound the problem by allowing much of our most fertile land to be covered by the endless junk of a consumption-mad society. Shopping malls, warehouses, parking lots, and physical fitness centers cover the wonderfully productive bottom lands of the valley near Seattle to which my family moved when I was ten. I grew up there, staying quite physically fit, along with a goodly number of other farming folks, weeding and thinning carrots, cabbage, lettuce, and radishes, and picking raspberries, strawberries, blackberries, cherries, beans, and peas. Our valley, and the other valleys around us, which now are nearly all filled with the same concrete redundancies, once supplied Seattle with luscious, nutritious, fresh produce which now comes from California in ever heavier, more numerous, more dangerous trucks polluting the air with the smog from wastefully burned non-renewable fossil fuels. Unless we depart drastically from our present trends, most experts warn us, more than half the cost of the food the average city consumer buys will soon go for transportation alone. The smaller farmer who cannot afford, as the vast farming corporations can, to engage in the transportation business as well as the food-growing business, finds herself/himself in an increasingly hopeless competitive position. Meanwhile, the multifaceted “vertical” corporation cares little whether its major profits come from producing food or simply carting it over highways obligingly subsidized by all of us captives of the supermarket, who can either buy the plastic tomatoes bred to withstand these long hauls or go without. I submit that the time is ripe for a novel examining all the human problems involved in getting an edible tomato from the field to the table of an urban apartment dweller. And I cannot believe that such a subject is not “large” enough for a “major” book. All that is necessary is the imagination of the right author and an intelligent reception by what the late Vardis Fisher called “the Eastern literary establishment.”

Twenty-two years ago this book was launched into a social and literary climate of apathy and nihilism. In 1960 Mary McCarthy delivered a lecture in a number of European cities asking, “Is it still possible to write novels?” She replied to herself, “The answer, it seems to me, is certainly not yes and perhaps, tentatively, no.” Two years later, with this novel scarcely off the press, I was being asked to participate in panel after panel which discussed the dismal question “Is the novel dead?” Part of the problem was that for three decades the critics had been praising—and sometimes writing—the books that seemed increasingly irrelevant to many readers of novels. Harvard professor Warner Berthoff summed up the situation in a Yale Review essay (Winter, 1979) entitled “A Literature without Qualities: American Writing Since 1945.” He wondered who could find that literature significant, “apart from a bureaucratized elite holding on for dear life to illusions of cultural primacy and the prerogatives and satisfactions of commodity-market ‘excellence’.” In his 1950 Nobel Prize acceptance speech William Faulkner had described the problem somewhat more poetically: “The young man or woman writing today … writes not of love but of lust, of defeats in which nobody loses anything of value, of victories without hope and, worst of all, without pity or compassion. His griefs grieve on no universal bones, leaving no scars. He writes not of the heart but of the glands.”

We had departed drastically from the views generally held by western culture since Aristotle first enunciated them—namely, that writers have an obligation to examine genuinely significant aspects of the human condition, and society has an obligation to listen to those writers for the sake of its own health. But in the last few years such questioning as Berthoff’s has signalled a greening of the literary world. In 1977 came John Gardner’s On Moral Fiction. In July 1983 Winona State University in Minnesota sponsored a writer’s conference which set itself to study, for two weeks, “The Writer’s Moral Responsibility.” Today we don’t seem nearly so far away as we were twenty years ago from that day in 1863 when President Lincoln looked down at the tiny woman standing before him and said to Harriet Beecher Stowe, “So you’re the little lady who made this big war!”

I am not alone in feeling that stories about such fundamentals as the food we eat and the way it is produced may once again command serious attention. William Kittredge and Steven M. Krauzer, introducing a special issue of TriQuarterly dedicated to “Writers of the New West” (Spring, 1980), conclude their essay:

Well, the other day some wiseass asked us to name a great writer who dealt with agriculture. How about Tolstoy? Sure, this fellow said, but that was a long time ago and in another country. This made us so impatient we had to shoot him down.

Perhaps we have good reasons to hope that many readers are waiting for books that explore the way we feel about the earth. Today, many of the people who cultivate and harvest our wheat never even look at the fields they work. Instead, they steer their gigantic tractors and combines by viewing those fields on closed-circuit television screens mounted in their cabs. Do they, can they feel the same way Rose and Will and Rachel and George and Lucy felt? Can we, with impunity, turn our eyes away from the earth and stare instead day after day into a cathode ray tube?

This seems a good time for The Bones of Plenty to come forth in a new edition, and I am grateful to Jean A. Brookins, head of the Minnesota Historical Society Press, and to Ann Regan, editor of the Borealis series, for this second launching. Faulkner ended his Nobel speech with these words: “The poet’s voice need not merely be the record of man, it can be one of the props, the pillars to help him endure and prevail.” I am glad this book once more has a chance to contribute its record, its props and pillars to our current struggle to endure.

Lois Phillips Hudson