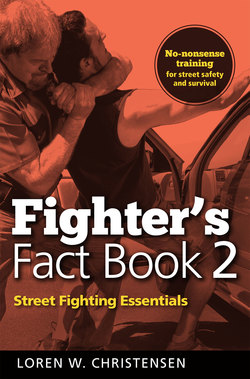

Читать книгу Fighter's Fact Book 2 - Loren W. Christensen - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4 TRAINING

10 Concepts to Adapt Your Training to the Street

By Rory A. Miller

It’s not enough to say that “the street” is different from the dojo. The street is different from the street. Real conflict happens in places, times, and with people. It happens for a reason, though the victim may never know what that is. The aggressor has motives, history and a plan. The professional violent criminal is one type of aggressor or threat. He has a system that he has developed through trial and error to safely and effectively neutralize you to get what he wants. There are many types of threats, and each type and each situation might require different skills.

You might be required to stop an elderly schizophrenic patient from trying to leave the nursing home. Since this is not the same kind of threat that a professional predator presents, it requires different techniques, tactics, and mindset.

A drunken relative who insists on driving is a different threat than a mob trying to flip and burn your car. A date-rape is a different threat than a bar fight. Next to surprise, the chaos and variability of real life is the hardest factor to train for.

When you bow into your dojo or shake hands at the start of a match, you know where you are, what the goals are, what to expect, and what it takes to win. In this sense, martial arts training is unitary. Whether you study arnis, judo or mixed martial arts (MMA), you’re studying to a single context.

It can get really messed up when what you’re training for (say, winning the next submission grappling tournament) doesn’t match what you think you’re training for (“I’m learnin’ to fight.”) Believing that you already have the answer to a problem not only limits your adaptability in seeking other answers but can prevent you from clearly seeing what the problem really is.

There will be tons of good advice and hard-won lessons in this book about the street: things to do, things to notice, and mistakes to avoid. The goal of this chapter is to look at your training and see it a little differently.

Concept 1: the tactical matrix and complexity

There are four ways a fight can happen:

1) You’re surprised: you’re the victim of an ambush.2) You were suspicious: you knew something was happening but you weren’t sure what.3) It was mutual combat: you knew there was going to be a fight and you were ready.4) You attack with complete surprise

There are three levels of force available that may be appropriate:

1) It’s not okay for you to cause damage.2) It’s okay for you to damage but not to kill.3) It’s justified for you to kill.

A matrix is a way of looking at how several elements can combine to change a situation. If you look objectively at your training, you can plug everything into the matrix and see where it’s appropriate and where it’s useless. Each technique, each tactic and each strategy fits somewhere in this simple box.

SURPRISED

ALERTED

MUTUAL

ATTACKING

NO INJURY

INJURY

LETHAL

Placing just these two variables, “level of surprise” in the horizontal column and “acceptable force” in the vertical column, creates a 3x4 matrix with 12 possible combinations.

SURPRISED

ALERTED

MUTUAL

ATTACKING

NO INJURY

INJURY

LETHAL

Fencing

I fenced in college. As it was taught, fencing (without the safety equipment) would only be appropriate in the Mutual/Lethal box. Can you modify this? Sure, I could always stab someone from the shadows with my epee, expanding to the lethal/attacking box, but that wasn’t how it was taught.

Strategy can also be placed on the matrix. For example, the essence of karate is to close the distance and do damage. We can argue about the lethality of the fist, but in general, striking is about damage. We can also argue whether or not strategy can be useful under surprise, but for sure if it’s not practiced under conditions of surprise, it won’t be.

Sosuishitsu-ryu jujutsu was designed for a last ditch effort to survive an assassination attempt, or when a combatant’s weapon was broken on a battlefield. It’s a brutal fighting system, one designed specifically around dealing with situations of surprise and disadvantage. But it generally sucks for mutual combat or attacking; that’s what swords and spears were for.

The defensive tactics (DT) I was taught at the police academy were based on taking a threat down and handcuffing him without injury. We were also trained in firearms, the Big Equalizer.

Comparative strategy matrix:

SURPRISED

ALERTED

MUTUAL

ATTACKING

NO INJURY

DT

DT

INJURY

Sosuishitsu

Karate

Karate

Karate

LETHAL

Sosuishitsu

Sosuishitsu Handgun

Handgun

Handgun

Notice that there are few or no strategies for surviving an ambush without causing injury. That is a simple fact that is hard for some people to stomach. Surviving an ambush is difficult. When you’re hampered with restrictions on how you’re allowed to survive it becomes even harder.

When you consider your training, look to see where it fits in the matrix. Can you execute a trap when you’re surprised? Can you justify using your reverse punch to get a senile grandparent to quit swinging his cane at the nurse?

Dojo training is much, much simpler than real violence. The matrix is a way to show that. In a simple list of 12 possible contexts for violence, it’s rare to find a style, strategy or technique that is appropriate for more than three. This is just a taste, because this matrix is far too simple. You could add an entire dimension with any variable you choose to consider.

Consider weapons. There are four ways weapons can come into a fight:

The defender has a weapon.The attacker has a weapon.Neither has a weapon.Both have weapons.

These four possibilities quadruple the size of the matrix. It would now contain 48 boxes in three dimensions.

Each uncontrolled element of the context of the fight expands the skills and knowledge needed and removes it farther from the unity of training.

Concept 2: Know what is going on and make a decision

Self-defense situations develop quickly. One key skill is the ability to decide what to do in an instant - then do it. If you’re ambushed, you will probably take damage before you’re even aware that you’re in a fight. Planning takes time and on the receiving end of an ambush, time is damage. All possible solutions involve moving: either running or fighting. You will make that decision in a fraction of a second with only partial information. Each second you spend gathering information to make a better decision is a second of injury to you. Damage makes it harder to implement your plan.

If you’re going to run, run. If you’re going to fight, fight. If you’re going to talk, talk. Keep your decision simple. If you decide to fight, then fight. Don’t think: “I must pass-parry the probable overhand right, side step to his dead zone and apply pressure to his chin and grab his shoulder, then pirouette …” Detailed plans fall apart under chaos. Simple plans don’t. Not as much.

Make a decision, make it fast, and act.

Concept 3: Discretionary time

How a person uses discretionary time is the defining difference between a professional and an amateur. To put it as simply as possible: if you have time to think, think. If you don’t have time to think, move.

The people who get stomped are the ones who felt something hit them from behind, and then they froze for a second to either figure out what was going on or to make a plan. Should this happen to you, the fact that you’re under attack is all the ‘what’ you need to know. Each second of planning or thinking is one more second of damage.

Conversely, if something is about to go bad but hasn’t yet you have time to think and plan, to evaluate options, available weapons and allies, and to look for escape routes. The more time you have and the better you use it, the more power you have, not only in any eventual fight, but in deciding if one is even going to happen.

Ways to get more time

The earlier your warning systems go off, the more time you have to make a good decision. Here are some simple ways to fine-tune your early-warning systems and buy some time.

Trust your intuition. If the hair stands up on the back of your neck, start looking for weapons, escape routes and threats before you try to figure out what is causing the reaction. If you don’t trust someone, think about how to get away or what you will do if they lunge at you before you try to rationalize your distrust.Make a habit of studying your surroundings. Always look for good escape routes, obstacles, and available weapons. Practice looking for subtle reflective surfaces and shadows until it becomes second nature.Learn all you can about how violence really happens and how criminals really work. Choose your sources wisely - there is a lot of bad information available.

In a mutual fight, you have great discretion to set the terms of the conflict. There is a predictable build up with easily recognizable steps. I call it the “Monkey Dance,” the human dominance display. The Dance can usually be averted by showing submissive body language (eyes down and an apology), or it can be circumvented by jumping steps, such as taking the threat down as he approaches, instead of waiting for the chest push.

More important is to realize that if you’re aware that something is building to a fight, you don’t have to agree to take it there.

Threat: “I’m gonna kick your ass.”

Me: “No.”

Threat: “What do you mean, ‘No?’ ?”

Me: “Just no.”

Threat: (hyperventilates a little) “What are you gonna do about it?”

Me: (sigh or yawn [I’ve done both]) “Look, it’s late and I’m tired. You already sound upset. Fighting would wake me up a little but I don’t see what you’d get out of it. What’s your goal here?”

Threat: “My goal? You’re a weird cat, Miller.”

Me: “I hear that a lot.”

The Monkey Dance

Animals do not fight within their own species the same way they attack prey or defend themselves from predators. Big horn sheep slam the hardest parts of their heads together in dominance games, but fight off coyotes mostly by kicking. Coyotes, on the other hand, snarl, posture and wrestle to get a grip on an exposed throat of another coyote, but they prefer to run a deer or sheep to exhaustion, slashing at its hamstrings and belly with their teeth.

Though it looks like a fight, the dominance game played within a species is nothing like predatory violence. The same is true for humans. Like any other animal, humans have a ritual combat they play with other humans to establish dominance.

The steps may differ by culture but in general the Monkey Dance follows:

1) Eye contact with a hard, challenging stare.2) Verbal challenge: “What you lookin’ at?!”3) The person closes the distance with a strut, his chest stuck out. Sometimes they actually bounce up and down like a rooster.4) A push or finger poke, usually to the chest. A finger poke on the nose will almost always result in an immediate swing.5) A hard overhand swinging punch.

It’s rare for someone to be seriously injured in the Monkey Dance. Injuries that do occur happen when one or both of the participants fall and hit their heads.

The Monkey Dance may start with a clear aggressor or a bully, but as soon as the other person responds, both are involved in the dance. When challenged in this manner, most people will respond following the same steps as the aggressor unless they are aware of it and disciplined not to do so.

Concept 4: Fight to the goal

In a martial arts tournament, you know exactly what constitutes a win: a throw for ippon (point), a knockout, or a tap out. What determines a win is decided before the battle and is predictable enough that you can train toward it.

It’s rarely that predictable in real life. The tactical matrix illustrates that fighting at different levels of force – restraint, damage, lethal - changes everything. A situation that requires you to restrain without hurting is completely different in presentation, options and goals than one that requires you to break a limb or to kill. It’s incumbent on you to recognize as early as possible which situation you’re in, and fight to that goal.

It would be easy if those were the only three possible goals. They aren’t. What you need to prevail (your goal) in each given situation may be wildly different.

You may need to fight your way past someone or several people to escape, which is different than standing and fighting. You may need to get your daughter or pregnant wife to safety. You may need to get the attention of near-by help. While curled into a ball being kicked from all sides, you need to stay calm and conscious long enough to poke 9-1-1 on your cell phone. During the ensuing battle, you might need to get one hand free to access a weapon. Whatever the goal in that instant, you must fight toward it and it must be the right one.

Example of an inappropriate goal

Several years ago, I debriefed a corrections officer after a use-of-force incident in which he had been attacked by a single inmate in a large open jail room with 64 other inmates watching. He was several minutes into the fight before he realized the inmate was trying to kill him: biting, striking and gouging the officer’s eyes. But the officer was only trying to go for a pin! He had been a competitive wrestler and his training had taken over. He had fought to an inappropriate goal and it could have cost him his sight or his life.

Concept 5: Use your environment

Most martial arts are practiced in an incredibly sterile environment: the floor is even and often padded, and sharp edges and corners have been removed. There’s no furniture to trip over, much less puke to slip in, or needles to roll over. The practitioners are stripped down to similar uniforms with sensible (or no) footwear.

The real world is full of curbs, doorknobs, furniture, and sharp-cornered concrete buildings.

It’s possible to drag someone off balance by their hoody, or blind them by pulling it over their eyes. You can immobilize a person lying on the ground by standing on their baggy pants. There are slopes and slippery places, and places where there isn’t enough room to turn around. There’s bad lighting, loud noises, shadows, and reflections everywhere. All the while traffic whizzes by.

The difference between a hazard and an opportunity is determined by who recognizes and exploits it first. A curb is a hazard if the threat makes you trip over it; it’s an opportunity if you push him over it. The list of potential opportunities is endless.

Reading about this isn’t enough. Thinking and visualizing isn’t enough. You need to practice your art in a variety of surroundings and deliberately use the environment in conjunction with your art. It takes a good amount of skill and a teacher who understands safety, but you need to practice recognizing when walls, corners, tables, electrical cords, random liquids, the threat’s clothes, and traffic can be used to your advantage. This can be dangerous. Even training in armor won’t help much should you throw someone into the corner of a table.

There is a big difference between this blood-smeared jail cell where officers had to fight a combative prisoner and that of the clean, sterile, and wide-open training area of a martial arts school.

Don’t let the sterility of the class environment blind you to available options. Use the mirrors and the weapons on the wall. Run for the door and yell for help in self-defense class.

Want to know one of the differences between rolling with your pals at the dojo and rolling with a tweaker (someone under the influence of methamphetamines) in an isolation cell? Hygiene. Your dojo pals don’t stink. Not like a tweaker.

Concept 6: Violence is a form of communication. So communicate

Cops often come into the job believing the Old West version of the gunfight and the quick draw. They pay lip service to the adage that “action beats reaction,” but they don’t really grasp it.

During “uncontrolled environment” training, officers participate with a full complement of safe weapons, including Simunitions (Sims are sub-caliber weapons, real guns that fire a marking pellet. The suckers sting, too. Ask to see the scars some time).

To demonstrate the action/reaction gap, I let two officers draw their weapons and point them at my chest with their fingers on the trigger. I have a Simunitions weapon in my hand dangling at my side. The officers are instructed to order me to drop the weapon, and should I make a threatening gesture, they are to fire. I consistently get off three shots before either officer can squeeze the trigger. If I sidestep with the action, they miss.

Then I have one of the students play the threat and I play the officer. The kid expects me to draw down and give commands. Instead, I scream, “Drop the weapon, do it now!” while leaping at him, grabbing his shoulder with my off hand, and spinning him to the ground. Not one trainee has fired a shot (except for the time I slipped like an idiot and fell). This demonstrates how action beats reaction, and the scream is key.

When you fight, scream and make it a sharp, loud, and simple command: “Stop!” “Get down!” “Drop it! Try to hurt his ears and shake the windows across the street.

Concept 7: This is not a game

There are no OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration, a government organization that ensures safe and healthy working conditions) regulations for an assault. When a boxer isn’t wearing competition gloves and he hits a skull, he breaks his hand. If you hit a threat in the mouth out in the street, you risk getting blood poisoning when broken teeth puncture your skin and his blood and saliva get into your body. Even if it’s only the other guy who does the bleeding, you sometimes wait for weeks for blood tests to know if you were exposed to hepatitis or HIV.

Those are the winning options. The loser may be paralyzed, blinded or permanently brain damaged. It’s easy for some people to say that they would risk their life for X, but the question is would they risk becoming a paraplegic and having to wake up to the same nightmare every day? Would they risk spending years in prison? Losing their house as part of a civil suit?

These are just some of the things at risk. It’s not as clean as is the romantic fantasy about dying heroically for a good cause. The stakes are too high for it to be a game.

Get them talking

This is a trick I picked up yanking combative bad guys out of cells, a situation in which the prisoner is ready to fight and you have to go through a door to put him down without hurting him. He knows from what direction you will be coming and that you will be moving directly through his prime striking range.

I use a fast lead hand and lead-leg drop-step to grab just above his lead elbow. Then I spin him. The trick is to make the move while he is talking so that he freezes.

This has been so reliable that now when I know I have to take someone out of a cell and I have a few seconds of discretionary time, I try to get the person talking. Then I move.

In training, there’s an emphasis on good technique and doing things right. “Start over,” sensei says. But there aren’t any do-overs outside the dojo. Sometimes you screw up, sometimes it’s sloppy. Tough. You work from where you find yourself because that’s all you have. You need to practice recovering from a position of disadvantage; accept mistakes as something that happens and work from the flawed position.

Fighting is too damn sloppy to be a game.

There are also habits in every style that are based on safety or entertainment that have become the “right” way to do the technique. Officers and soldiers put prisoners face down for control, wrestlers and judoka put them face up because it makes for a more entertaining and challenging match. The follow-through for a judo hip throw is taught as a control maneuver to get an easy pin or arm-lock, but it was a safety modification from the older follow-throughs that put the thrown person’s falling weight directly on the point of his shoulder or bent neck. The pronated fist of karate was a Japanese innovation to decrease the training injuries common to the original Okinawan art. Over time these safety and entertainment changes have become the “right way” and “good technique.” Study your training for things that have been added to make it safer or “more fun.”

Breaking the turtle

The turtle is a defensive position common to most grappling styles. The opponent is on hands and knees, facing the floor, back rounded to use the abdominal muscles to best advantage in resisting being lifted or straightened. In styles where uniforms are worn, the turtler’s hands are often inside the collar so he can protect himself from strangles. This position isn’t a fight-winner, but it’s a solid defensive position where an opponent can rest and think.

I’ve spent hours learning different ways to break the turtle. I’m partial to a trailing arm flip over strangle, but truth is it’s a useless move. Imagine you’re in a bar brawl and someone turtles up. So what? A guy curled up and face down is not a threat. If he reaches for a weapon he becomes a threat, but you do not engage by grappling him. You leave. Or you use a weapon of your own. Or you apply your boots to him.

The exceptions are law enforcement and corrections officers who have to handcuff a threat from the turtle position. But even then there is usually time to bring more people or tools into play.

Concept 8: Intent, means and opportunity

For a person to be seen as a valid and immediate threat, he must exhibit three elements: intent, means, and opportunity.

Intent means that he wants to hurt you.Means is his ability to hurt you: fists, knife, or gun.Opportunity allows him to reach you with the means.

To claim self-defense, the threat must present all three of these elements and you must be able to explain clearly how you knew all were present.

If you can take one of these away, he ceases to be a threat. If you can physically beat him up you deny him his means. If you can get away, he is denied his opportunity. If you can change the threat’s mind, you have altered his intent. Altering intent is a broad and potent skill. You can do it by projecting calm, bluffing, using humor, emitting an ear splitting scream, and a number of other ways.

The art of fighting without fighting

Besides attacking a threat physically, you can attack him mentally. You can attack the relationship and you can attack the context.

Attack mentally This is a direct attempt to influence his mind. For example, loud and unexpected noises can freeze the mind for a second. So can non-sequiturs, odd phrases that make the threat reevaluate the situation.

On one occasion we had a large, violently psychotic inmate screaming threats. When he took a breath, I said softly, “I know. But you tried really hard and you did well for a long time. No one can ever take that away from you. I’m proud of you.” He let me cuff him.

Attack the relationship To do this you must understand what dynamic you’re in. You and the bad guy are both playing a role, so if you change the one he has assigned to you, you change the relationship.

Threat: “What you starin’ at?”

Me: “Sorry, man. Worked a double yesterday and I zoned for a minute. How you doin’?”

Attack the context This requires a global awareness: you must know what is going on and what the threat thinks is going on. If he is attempting to put on a show for his friends, try to remove the friends. If a predator believes you’re alone and vulnerable, start talking to someone out of the threat’s line of vision or make a cell phone call. My personal favorite is this: when the threat sees me as a potential victim and I have a three-way conversation with Jesus and Elvis while rhythmically twitching, the threat tends to change his mind.

Concept 9: You won’t have your normal mind or body

Remember the first time you asked someone out on a date? Your mouth was dry, your palms were sweaty, your knees felt weak, and you were unbelievably clumsy. After hours or days of working yourself up to it you were still barely able to stammer out the words. Compare that high anxiety moment to having a casual chat with your friends.

Your fighting skills in real life will degrade about as much as your verbal skills did when asking that person out. This subject can get complex.

As the stress hormones hit your system, your perception can alter:

You might not be able to hear anythingYour eyesight might become incredibly acute but without peripheral vision, or just a blur.You might not be able to feel anything with your fingers.

Your mind will alter:

You might lock onto an idea and, though it’s not working, you’re unable to do anything else.Everything might appear to be in slow motion, but still you can’t move.You might feel calm and peaceful as horrible things happen to your body, or to a friend’s, and you don’t feel like doing anything about it.You might meekly obey when you know you shouldn’t. Many victims of horrible crimes comply simply when ordered to or when they are only threatened with violence. I had a 400-pound veteran jailhouse fighter meekly get on the ground when ordered just because of volume, intensity, and surprise of the command. I never had to touch him.

Important point: a training environment that emphasizes instant obedience to any authority figure or shouted command may make the students more vulnerable to this kind of assault.

Your body will alter:

Your finger dexterity might be gone (loss of fine-motor skills).You might not be able to move your arms and legs at the same time (loss of complex motor skills)Your limbs might feel heavy or numb.

After putting a 240-pound jail guard through a scenario that was an emotional wringer, he leaned over, and panted, “Sarge, I feel like I’m gonna cry and I want to puke. Is that normal?”

It was perfectly normal. Even though he did everything right and had performed excellently, his adrenaline had still gotten to him.

Are there ways to deal with this? Yes, but it’s not easy. Experience is the best system for adrenaline control but it can be hard to survive enough encounters to reap the full benefits. Here are two pieces of advice:

If you’re in a bad situation and you get a warm and happy feeling like you’re floating – you’re frozen. Recognize the state, and act. Move, punch, scream, or run, but consciously do something. Then do something else. That usually breaks you out of the freeze.Get used to things going badly. You only have to use unarmed defensive skills when everything else has gone wrong, so take every opportunity to practice recovering from bad positions.If tournaments scare you, compete.If someone in your class always beats you, spar with him every day.Keep going even when you’re exhausted.If you slip and fall, fight from there and insist that your training partners take advantage of the opportunity, just as a threat would.

Concept 10: A threat isn’t your training partner

You should see a pattern by now:

Martial arts are relatively safe, fun and healthy.Fighting is dangerous, unpleasant and potentially crippling.Martial arts are practiced in a clean environmentReal fighting happens in alleys, bars, and public restrooms.In martial arts, you know what you’re getting into.In a fight, you might not know if it’s a wrestling match or a knife fight until things get slippery.

Here’s a big one: you practice martial arts with your friends, people who enjoy spending time with you, who enjoy the art that you enjoy, and who are dedicated to becoming, and helping you become, a better person.

A threat may hate you or despise you with a level of venom that you can barely comprehend. Or the threat may feel no emotion whatsoever, viewing you as nothing more than a source of cash, gratification, or a convenient toy to vent some rage. He might be responding to voices in his head that only he can hear or playing out a scripted fantasy of torture, rape and murder that he has cherished since childhood.

You can’t break your partners in training. The ones you spar with tonight will be the ones you spar with next week. The fact that you’re training specifically to break human beings but at the same time you cannot break your training partners is the source of most flaws in martial arts.

This need to recycle training partners affects what is taught in a martial arts class, and it affects how it’s taught. If you have ever been told “We don’t do that here, it’s too dangerous” or “that’s not allowed in a tournament” take a good hard look at why. If you fight non-contact or you hit with contact but only to relatively safe targets, you have been practicing to miss. It becomes a habit and, under stress, you will miss just as you have trained to do.

Serious competitive martial artists have stated that just because they don’t practice a technique doesn’t mean they can’t do it. Wrestlers have said that just because they don’t practice eye gouging doesn’t mean they can’t do it. In theory, it’s a pretty good argument. What actually happens, however, is that these fighters don’t even think of using the illegal techniques because they fight the way they have trained. Then, when a threat uses a technique that the martial artist knows as an illegal one, he freezes for a second to reorient. I have actually seen officers getting their asses kicked while looking around for a referee. You fight the way you train and the more intense the training the deeper the habits are ingrained.

That it’s hard to train not to injure friends is one half of the problem. The other half is that because of the context of the conflict, threats don’t react like training partners.

Most criminals have never been taught to flow with a joint lock or respond in the specific way that you need to make your favorite combination work. Threats who are emotionally disturbed, drunk, drugged, or angry, might not feel pain and won’t react to it as your training partners do. Threats have a tendency to flail fast and hard in a continuous jerky action as opposed to those smooth, trained responses you practiced against.

Real threats try to get close to either blitz or sucker-punch; they don’t face off at the critical distance line. They don’t play the skill and timing game of feint and counter attack. They aren’t trying to win; they are trying to hurt you. Threats haven’t been taught that a broken nose is a fight-ender.

Look at your training and ask yourself:

Can I do this if my partner goes full speed?Can I do this under the pressure of a flurry of attacks?Will it work against a weapon?Can I still do it if I can’t see clearly?Does it take more space than I am likely to have?Do real criminals attack the way my partner does in this drill?Would it work on me if I were very angry?

In the book “Battle Ready” General Anthony Zinni noted that the lessons he had learned in the jungles of Vietnam didn’t help in the Highlands or the rice paddies. Think about that. If the skills of war fighting in a jungle don’t help in mountains, swamps or cities, be very careful in presuming that the skills of the ring will help in the chaos of a riot. It’s not just that the dojo isn’t like the street.

The street isn’t always like the street.

Sergeant Rory A. Miller is a corrections officer and tactical team leader for a 2,000 bed jail system. He has studied martial arts since 1981 and worked with inmates since 1991.

At this writing, Rory has participated in over 300 unarmed violent encounters against lone convicts and groups; inmates with and without weapons; inmates on PCP, methamphetamine, and other drugs; and inmates in full-excited delirium.

He teaches and designs such classes as Use of Force, Defensive Tactics and Confrontational Simulation for his agency and, privately, he teaches Sosuishitsu-ryu jujutsu, a Tokugawa era system of close combat. Sergeant Miller has taught seminars around the country.

Rory does his thinking aloud at www.chirontraining.blogspot.com

Many thanks to Luke Heckathorn for posing and to Kamila Z. Miller for her excellent photography.