Читать книгу The Collected Poems of Lorenzo Thomas - Lorenzo Thomas - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

Laura Vrana

In his indispensable study Extraordinary Measures: Afrocentric Modernism and Twentieth-Century American Poetry (2000), Lorenzo Thomas astutely observed: “The creative activity of African American writers, of course, also paralleled, influenced, and responded to social and artistic developments in the national ‘mainstream’ culture. This fact [is] largely ignored in ‘standard’ American literary history.” The accuracy of this sentiment is reinforced by the tragic—if predictable—neglect to which it was subsequently subjected by that “standard” literary history. Yet those interested in American poetry writ large and African American literature across genres must attend to Thomas’s view, as well as to his oeuvre of work both critical and creative, which has been undervalued for several linked reasons.

First has been the inaccessibility of much of Thomas’s poetry in widely available editions, due to the ephemeral means by which he often disseminated it; this collection gestures toward filling that lacuna, though this same ephemerality has regrettably made it impossible to be as comprehensive as might hopefully be attainable in the future. This impossibility points to the second problem preventing full recognition of Thomas’s integral role in American and African American literature: his inclination toward experimenting with myriad aesthetics in modes both serious and light-hearted. Like several others who have had the good fortune to become better known, notably Harryette Mullen, who cites him as a key influence, Thomas’s refusal to remain within the traditional boundaries erected around African American literary aesthetics often took the form of linguistic and surrealist innovation, inspired by visual artists, writers, and musicians ranging from Robert Johnson and Lightning Hopkins to Aimé Césaire and John Ashbery. Thirdly, Thomas’s defiance of geographical and institutional norms left him susceptible to exclusion from subsequent scholarly evaluations of the multiple communities with which he claimed affiliation throughout his career, such as the New York School—with which he was tied via the “Tulsa Group” through Ron Padgett’s White Dove Review and Ted Berrigan’s C Magazine—and the Umbra collective. His move to Texas in 1973 and his two-decade career at the University of Houston–Downtown positioned him at the vanguard of dramatic changes in institutional relationships with black writers.

Thomas served as a key connecting force himself, sharing little-known literary and musical artifacts and speaking across the country until his death in 2005. Even as a teen he had performed this role, editing a little magazine, Lost World, a 1961 copy of which contains one of his early verses, included here. In an interview with Hermine Pinson published in 1999 in Callaloo, he described this role:

If African-American culture is really going to be properly appreciated, I think what has to happen is that we have to have institutions that we can nurture into longevity even if we know that a half century from now they might be doing something quite different than you and I and today’s contributors can even imagine. That’s the purpose of having an institution. They will carry on some of our dreams and needs, right? And they should also be constructed in such a way that they will be responsive to a future that we might not even be able to foresee.

It is in this capacity as a preserver of black culture, and through his contributions to documenting a literary history that he was more integral to creating than has been acknowledged, that Thomas’s work lives on most directly. Yet his unique poetic style renders another unsung contribution, essential to ongoing scholarly efforts to expand the aesthetic and topical boundaries of the African American literary canon. With the publication of several collections and numerous more ephemeral works over five decades, alongside major essays and studies that helped to shape black literary study, Thomas’s works affected American poetry and African American literature from the Black Arts Movement through the contemporary era.

Born in 1944 in the Republic of Panama to politically conscious parents who viewed their world through the lens of pan-African global identity, Thomas would carry throughout his life an unshakably Afrocentric, transnational view of the black experience that never altered even as social contexts shifted. This birthplace meant that Spanish was Thomas’s first language and English his second, birthing a skepticism about the supposedly self-evident nature of linguistic structures, semantic rules, and grammatical logics that shaped his playfully experimental and pun-laden approach to poetry. Like Mullen, he occasionally intersperses multilingualisms in a casual manner that still registers as disruptive to some; yet earlier twentieth-century movements that inspired Thomas, including Negritude, displayed similar transnational and multilingual impulses. Thomas pointed out in a 1981 Callaloo interview with Charles Rowell that “If you read the African writers who write in Portuguese, you’ll find that they were inspired by Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes…. Hughes was inspirational in Portuguese-speaking Africa and in French-speaking Africa; he was a wonder in Central and South America, where many proclaimed him as the voice of the people, someone to emulate.”

Thomas’s poem “Robert Williams, Exiled in Cuba” opens by addressing two Cuban artists, poet Nicolás Guillén and visual artist Wilfredo Lam, with a diasporic intimacy that asserts a global and Afrocentric view of blackness. He asks Williams to “[l]ook in the streets / for a dark boy … / find him and say, ‘Lorenzo’s / in New York this winter and, you know, he’s black too.’ // Lorenzo, born in Panama, could look from / his playpen, see the Canal Zone, the stars & stripes. / Could see Uncle Sam’s guns aimed at the nazi [sic]. / Lorenzo, flying to the states in ’47, / Stopped over in Havana one hour, remembers little.” The memory detailed runs deeper than one individual’s, illustrating Thomas’s lifelong commitment to an intellectual and artistic exploration of the worldwide reach of American militaristic imperialism and, simultaneously, the empowering possibility of global black identification. The depth of this commitment transcended biographical circumstances and location, following Thomas and shaping his artistic and critical output throughout his career even though, as the poem narrates, he left Panama at a young age.

Raised in the Bronx and Queens after the international flight imagined in his poem, Thomas earned a B.A. in English Literature from Queens College and began graduate work toward an M.L.S. from the Pratt Institute. While at Queens College, he also joined what would become one of the earliest and most pivotal organizations of the Black Arts Movement: the Umbra Workshop, founded in 1962. During this period, Thomas was influenced by older Umbra artists including Ishmael Reed and Archie Shepp: the multi-genre works produced by such participants as musician-writer Shepp and writer and visual artist Askia M. Touré (then known as Roland Snellings) also affected Thomas’s work long-term, encouraging him to incorporate art (often by his brother Cecilio, a commercial artist and book designer) and innovative symbols into his texts, to become a powerful performer of his own work before all types of audiences, and to rely on music as a primary source of inspiration. Thomas was one of the youngest members of Umbra, and his essays and interviews prove an essential source for writing its history; nevertheless, he was too often omitted from early narratives of the workshop, since he became partly disassociated from it before its later controversies.

For in 1968, during the Vietnam War, like other black poets such as Yusef Komunyakaa, Thomas entered the military, serving four years of Navy duty that included education in the Vietnamese language. That was the same year Larry Neal and Amiri Baraka edited and published the influential Black Fire, key anthology of the Black Arts Movement, which included Thomas’s work. Thomas’s exposure to other languages and his military experience resonate throughout his mature verse. Unlike Baraka, Thomas was discharged honorably in 1972; he moved the next year to Houston, where he would make his home intermittently for the rest of his life.

This dislocation might seem an odd move at the height of the Black Arts Movement, which critics tend to view as centered in urban hubs on either coast. But highlighting Thomas’s story furthers recent efforts to illuminate the geographical diversity and divergences of the movement’s practitioners beyond those obvious poles, as he articulated in the 1981 interview with Rowell: “[t]he Black Arts Movement of the Sixties was never very far from the South.” Mullen has called Thomas “one of the messengers who brought the Black Arts movement below the Mason Dixon Line” (see the essay “All Silence Says Music Will Follow: Listening to Lorenzo Thomas,” in her book The Cracks Between What We Are and What We Are Supposed to Be). We might even view him as having been ahead of his time, for the move was precipitated by accepting a position as writer-in-residence at Texas Southern University; among the first black writers to work in public schools in this capacity, he then filled the same role at Florida A&M University and for the states of Arkansas and Oklahoma. While black writers inhabiting such positions has since become common, this trend was just beginning in the early 1970s, when Black Studies programs and departments were first being established.

Like better-known Black Arts Movement practitioners, Thomas remained devoted to working in his community alongside these university spaces. He helped to edit the arts journal Roots out of the Black Arts Center in Houston, where he also taught writing workshops, another demonstration of his role in cementing the cultural centrality of black artists and writing a history in progress. He became active with the Texas Commission of Arts and Humanities and served on the board of directors of the Coordinating Council of Literary Magazines. Further, he organized the Juneteenth Blues Festival in Houston and other cities, directed the Cultural Enrichment Center at the University of Houston–Downtown, and reviewed books for the Houston Chronicle for many years. He won a National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing Fellowship in 1983 and the Houston Festival Foundation Award in 1984. On a panel for a 2002 American Studies Association conference, Maria Damon argues that in Thomas’s work

Afrocentric poetry is historiography, and Afrocentric literary historiography is a form of social witnessing…. to write the extraordinary linear measures of poetry is to link one’s own survival to that of one’s community. To write history through poetry and a poetic historiography is to knit oneself even more closely to community. Healing the split between history and poetry, literary history, itself a poetics, can be a way of situating poetic practice in a social context—one’s own. By looking at Lorenzo Thomas’s literary historiography, we get a sense of how a poet’s rendition of history foregrounds the poetics of community formation and historical transformation.

The history surveyed in Thomas’s work ranges from ancient Egypt and Afrocentric cosmological mythologies to contemporary American incursions into Vietnam, extending the legacies of Ishmael Reed’s early poetry—which similarly integrated ancient myth and twentieth-century political critique—through the changing contexts of the Civil Rights movement, subsequent neoconservative retrenchments, and twenty-first-century iterations of racial terror.

Thomas’s continuing in-between aesthetic positionality—by which his work fit either into no aesthetic school or many, depending on whom you query—resulted in such seeming anomalies as his name being proposed as the sole potential black contributor to L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E magazine in early discussions among Ron Silliman and the editors. Like Baraka (then LeRoi Jones) in Donald Allen’s anthology The New American Poetry (1960) and later Erica Hunt in Silliman’s anthology In the American Tree (1986), Thomas ultimately became the only black writer to appear in that publication. At the same time, he was publishing poetry and criticism widely in such venues as African American Review, Ploughshares, and the African American Encyclopedia, focusing on black literature and music with a critical astuteness that culminated in a posthumous collection of essays, Don’t Deny My Name: Words and Music and the Black Intellectual Tradition. Such rigorous boundary-crossing in terms of publication venues and connections to other writers seems especially unusual when one considers Thomas’s indebtedness to an aesthetic of Afro-surrealism, frequently inspired by Cesaire and in tune with black musical innovation in all genres, including (as Mullen has written) “jazz, blues, R&B, rock, reggae, calypso, zydeco, disco, country western, western classical music, and even muzak.” But understanding this defiance of boundaries in (literary and musical) aesthetics and in publication is essential to reading Thomas’s work, as my co-editor’s Introduction details: his artistic statements (several of which are included at the end of this collection) decimate categories. As he articulated in a 2001 interview in The New Journal, his poems

are influenced as much by Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery as by Amiri Baraka and Calvin Hernton…. what I learned from Ashbery reinforced what I learned from Wallace Stevens and both Ashbery and Baraka reinforced what I found interesting about the colloquial language that I found in Langston Hughes and Carl Sandburg. And, of course, it is a fact that Hughes learned something from Sandburg, too. I guess that is how poetic influence connects you to a tradition. But in this sense I am not suggesting that tradition is a readymade thing.

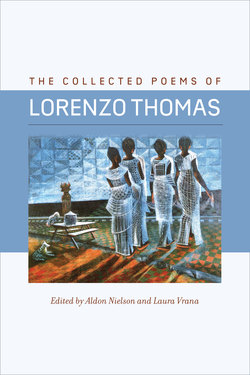

Indeed, Thomas was always engaged as much in making traditions as he was in suggesting their preexistence, though—as with his critical assertions—those intersecting influences in his work have often been ignored. The resulting neglect of the range of poetic texts Thomas produced, even including a 1997 bilingual German edition of his poems, began to be rectified near the end of his life. His final collection of poetry, Dancing on Main Street (2004), featured on its cover praise from Ashbery: “Lorenzo Thomas’s poems have a graceful New York School nonchalance that can swiftly become a hard and cutting edge when he writes of the African American experience, especially in his adopted home of Texas. ‘This useless clairvoyance / is embarrassing,’ he confides. Yet Thomas’s brand of clairvoyance is not only useful, but beautiful.” That implied divide between “New York School nonchalance” and the “African American experience” rarely plays out in the poetry, which interweaves so many supposedly disparate locations and experiences. Like Mullen, Thomas cleverly “puts the wit back into witness” (as Maria Damon said, quoted by Kalamu ya Salaam), satirically critiquing in often amusing verses Western imperialism, reliance on technology, and understandings of science as irreconcilable with spirituality.

Indeed, Thomas’s clairvoyant ability to foresee our moment of black poetics breaking down the boundaries that have attempted to delimit its subjects and forms should render him of special interest to anyone entranced by the recent flourishing of black poets’ work. He asserted in the 2001 New Journal interview that “a great deal of poetry” seems “to resemble the mental work that occupies us when we are in a condition somewhere between sleep and waking. It has a quality of almost obsessive attention to detail.” This evocation of a state halfway between sleeping and waking brings to mind both the surrealist and ancient forms of imagery of which Thomas was fond—and the ghastly realism with which he concisely, comically rips away the veil on American war crimes and the modes of thinking that prop up its methods of domination. In this, his work resembles Reed’s and Baraka’s. But in other ineffable ways, Thomas’s poetry resembles no one else’s work at all, the contributions of a singular voice whose unification of seemingly distinct interests helps us to rethink what we believe we know of American poetry and African American literature.