Читать книгу The Collected Poems of Lorenzo Thomas - Lorenzo Thomas - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Aldon Lynn Nielsen

“If everybody had an ocean …”

—Brian Wilson

“And the orders came down

As your prophets demanded. Strange FM stations

And astrological phone calls hastened to soothe you.”

—Lorenzo Thomas

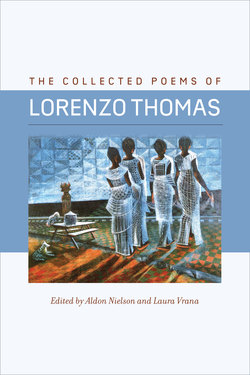

Admittedly an odd place to begin: mid-1960s, California’s white children with their endless summer surfing safari; perhaps not the anticipated opening onto the work of an artist who came of age as a publishing poet at the height of the Black Arts Movement, one of those “Umbra Alums” Harryette Mullen commemorates in her writing. Still, if, as Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys imagined, everybody had an ocean across the U.S.A., then Manhattan and Manhattan Beach might each take a different view of the interior, and that view might well resemble the collaged bacchanal of cleansing and consumption offered up by Cess Thomas in the cover art to Lorenzo Thomas’s 1981 collection The Bathers, which included earlier works,. Or, turning the page, it could look much like the baptism of Birmingham, that Alabama city that liked to call itself “A good place to raise a boy,” the “magic city” that mounted a dogged attack upon its own citizenry in an effort to drown out, as Thomas writes, those “infinite legions of us. Those who toil.” Still again, if everybody had an ocean we might gather together on the shore depicted on the cover of 1972’s Fit Music and wonder what rough beast, its hour come round again, trumpets its resurrection from the foam.

Which should remind us that there were already other beach boys:

They were all on the beach, and there were many others besides them—white men, brown men, black men, Finns, Poles, Italians, Slavs, Maltese, Indians, Negroids, African Negroes—deportées from America for violation of the United States immigration laws …

This surely is a census of the infinite legions of us, of those who toil, yet it is just as surely not the scene depicted in all those Beach Party movies of the ’60s, in which Frankie and Annette’s close personal friends, Stevie Wonder and the Supremes, would drop by to knock out a tune or two of fit music for the gathered bleached tribes, but who were never to intrude further into the plot lines and lives of America’s white children. Rather, these were the beach boys of Claude McKay’s Banjo, circa 1929 on the dock of the bay, in Marseilles. If everybody had an ocean, and if that ocean were not quite as segregated as the cinematic sea offered up by Hollywood, then Annette Funicello and Lincoln Agrippa Daily, known among the beach boys as Banjo, might Twist together in the daily rushes.

Brian Wilson once explained to an interviewer from Time magazine: “We’re not colored; we’re white. And we sing white.” The real story was, as it always is in America’s racial cosmology, considerably more complicated than the Beach Boys allowed. Lorenzo Thomas would have recognized that on first hearing. “Surfin’ U.S.A.” had as co-author none other than Chuck Berry, whose melody, blues progression, patented guitar licks, and even idealistic, adolescent longing are at the core of what Brian Wilson made from the materials of Berry’s composition “Sweet Little Sixteen.” Berry and the Beach Boys, too, shared a common shore of enunciation. The hard “R” sounds and wide-open vowels of Brian Wilson’s plain statement resemble nothing so much as the dialect of the plains, the natural affect of Missourians like Melvin B. Tolson and Chuck Berry. (It’s a sound that marks the Beach Boys apart from the Okie-inflected pronunciation of so many of their neighbors, not to mention the Armenian strains of contemporaries of theirs such as Cher.) This, unlike the musical appropriations, was not a matter of conscious mimicry, the sort of thing that explains why so many fifteen-year-old white boys in Iowa now sound as though they grew up in the Bronx. But it does raise a rather obvious question: When white people say that someone sounds “black,” what do they really mean? Brian Wilson says he sings white, and if that means that he sounds a lot like Chuck Berry, then we need to wonder just what is fit music for an America always at war with its own racial present?

Such questions are unavoidable when reading Lorenzo Thomas. How do we account for a poem titled “Negritude” that begins with beach boys:

They swim they play the surf for pridefulness

Their slim boards vanity you see them spread over the pages of

Life …

We would have to begin by recollecting that the founding poets of Negritude found themselves far from home, writing from the banks of the Seine in notebooks of a return. We would also have to acknowledge the ambiguous connotations oceans hold for black American poets. Lucille Clifton remarked to me how long it took her to be able to celebrate the Atlantic, where the traces of Middle Passage still gleam fathoms deep beneath the tempest. She said that she is able to contemplate the Pacific in another way. But there another order of oddity prevails. In Thomas’s “Fit Music” we read: “The sun people bleach their hair in the sun // If I mention Isis they ready to fight.” The Pacific fronts on Vietnam, which brings Lorenzo Thomas to the central questions posed by “Fit Music.” If Ezra Pound’s Confucius fits into a poem that Thomas subtitles “California Songs, 1970,” we can explain it in part by the Pacific Rim of association. The shores of the Pacific, whose very name disarmingly connotes peace, are shared by Kung, Buddha, and the Beach Boys. James Brown’s “Is It Yes Or Is It No,” the song seemingly unique among Brown’s prodigious output in never having been reissued on a CD compilation, might seem nominally less Pacific in orientation. Still, it too finds its way into the mix alongside Pound and Wilson, as all three were not only part of the soundtrack of Thomas’s California dreaming, they were also, as Thomas’s note to the poem slyly states, poets to be acknowledged for “their timeliness and aptness of thought.” (In those days, it has to be said, James Brown was always right on time.) The New York Times advertises itself as the reliable source for all the news that fits. Pound prescribed a poetry as news that stays new. Thomas’s poem, like any breathtakingly novel remix, takes as its point of departure all music that is fitting. “Is It Yes Or Is It No” fits in any number of ways. The open-ended question of Brown’s title suggests the seriality of Amiri Baraka and the then New Jazz, the compositional techniques that could be taken in hand to great effect by such disparate artists as Ornette Coleman, Charles Olson, and Baraka.

When the poet of “Fit Music” felt the draft, it was decision time, Canada or conscription? “It was time to be going,” we read in the “Proem,” to “Vancouver,” site as it happens of a most famous ’60s symposium of the New American Poetries, “or South Viet Nam.” “Is It Yes Or Is It No” was released side by side with Brown’s string-drenched “It’s A Man’s Man’s Man’s World,” a song whose instantly recognizable chord patterns formed the basis for Alicia Keys’s signature hit “Falling.” Though these Brown songs were considerably more gender-troubled than “I’m Black and I’m Proud,” they still serve to frame “Fit Music.” What’s a man to do? Confucius, Thomas recollects with the aid of Pound’s troubled translations, “went on plucking the k’in and / Singing the Odes.” Yet Pound was a “certified madman,” confined at Saint Elizabeth’s Hospital by the same state the poet now contemplates from a farther shore.

“Here in beautiful California,” he notes, “the surf remembers another form / of revolution.” Begin by taking this as literal truth, surf being a gravitational memory of the moon as the globe makes its revolutions. The poet is marking time, recalling songs and “Sending back reports from the beach.” It is a curious space to inhabit, westward in anticipation of transhipment to a war in the East. Admonished, as it were, to get ready to get your ass “in gear.”

“Little Honda,” though still available, occupies a position in the Brian Wilson oeuvre as anomalous as the fate of James Brown’s “Is It Yes Or Is It No.” It did appear on a Beach Boys album and was released as a single, but most people’s memory of the song is of the radio-hit version performed by The Hondells, who also appeared playing the song, of course, in one of those seemingly countless beach party flicks. It is rather as if “Sweet Little Sixteen” were known primarily through the Beach Boys’ shadow version. But the fact that there was a hit record titled “Little Honda” at all speaks to the slippery political and historical terrain of Thomas’s poem. Only two decades following the Second World War, millions of American teens clasped Japanese-manufactured transistor radios to their ears and tapped their feet to a theme extolling the virtues of a Japanese vehicle. What tenor was being read out of this as troops enplaned again for war in Asia. The opening stanza of the eighth canto of “Fit Music” begins, in Poundian fashion, by incorporating the chorus of “Little Honda:”

First gear it’s alright

Second gear. Lean right

Third gear, hang on tight

Faster

But the poet’s report from the beach ends on a more ominous note. Where the Walter Cronkite of the time signed off on his daily reports by intoning, “That’s the way it is” (this authoritative voice itself the very reason many on the Right to this day hold Cronkite personally responsible for pronouncing the war in Vietnam a losing proposition), Thomas declares, “That is what’s happening in the time warp.” This is a time warp he shares with all who, like the Canadian “dangling man” of Saul Bellows’s novel, await war. Back in the day, no matter our draft number, we greeted one another with a most sincere request for a status report. Asking “What’s happening?” of one another had a particular edge at a time when one’s fate could so easily change from moment to moment. Brian Wilson’s “First gear, it’s alright” was one Zen-like response. More to the point was Stevie Wonder’s “Baby, everything is alright, uptight, clean out of sight.” Here, in the time warp of our own habitation, as we again wait to find out if we will be at war, our answer is the much attenuated “aiiiggghhhhtt.” Wilson’s gear-shifting response had existential concision to recommend it; rather like the old joke I first heard from Gil Scott-Heron about the man who jumped off the Empire State Building. As he fell past the open windows of each subsequent floor, the workers inside could hear him saying, “So far, so good.” As the ’60s became the ’70s, the question was how that sense of alrightness was to be asserted against the conjoint madness of war and racism. Thomas offers us his “Proem” to “Fit Music” as a gloss, “Deja vu more or less,” and what could be more familiar to us now, as the raptures of rampant globalism give way to the same old saber rattling, than the Proem’s beachside second-person address:

You spent childhood rehearsing the Korean War

You fucked up in college and picked the wrong major

And in 66 everyone faked concern for Asia

It was all more fitting than you thought;

The staging.

It was Chuck Berry who warned us to look out for the safety belt that wouldn’t budge. When the orders reached us in that long, dark staging area of the soul, what was left but to seek fit music? “Without character,” Kung cautions in Pound’s thirteenth canto, “You will be unable to play on that instrument.” Pound or Brown, Beach Boys or Berry, all go to comprise the poet’s character as he confronts the calamity not of his own making, as “An ignorance and circumstance // somehow involve [him] / in their fathers’ greed.”

There is an envoy, a return to California at the end. Thomas’s “Envoy” recalls us to its double reading, and the poet, like the reader, has much to answer for:

How did you like being the envoy of a monstrous epic

Or saga of Western corruption

When the white guys blacked their mugs

Before the ambush, what did you do kid?

What sort of ambush is it when the Beach Boys borrow blackness as a means to be white? What does it mean when bleached boys blacken their faces to attack in the night? Why are they so ready to fight at the mere mention of Isis? What might it mean that this envoy wraps itself around a strand of musical DNA contributed by James Brown?

As it says in the song making me

Suffer was it fun

Making me suffer

Now I want to know

In Thomas’s lineation, it is the song that makes him, as well as the song that makes him suffer. (I remember a great song by John Lee Hooker, one of those existential Blues that underscores our basic sense of our condition, titled, “It Serve You Right to Suffer.”) One thing the poem intends is a counter narrative.

In the aftermath of withdrawal, a time often marked by a sense of regret and exhaustion, a myth took hold in the American media, a story of returning Vietnam vets being spat upon in the airports of our nation, as though these were filled at the time with impolite, well-traveled Leftists. The fact that not one credible historian has been able to confirm a single instance of this behavior has done little to dislodge the mythology, whose political power is still deployed in contemporary debates over war and patriotism, though, to judge from the malicious treatment of Vietnam vet Max Cleland in his re-election campaign, those who have availed themselves of this mythology are seldom really interested in benefitting any actual veterans. What Thomas’s envoy tells us is of an infinitely more disturbing order:

I wanted somebody to stop me at the airport

And ask me all about Vietnam

But nobody asked me

This surely is part of what it means to stand as an envoy of a monstrous epic, to feel oneself an unattended afterthought, to stand on the stage after the song itself is through and ask, “Was it fun / Making me suffer?”

What welcome does greet this envoy is the golden arch of a San Francisco McDonald’s:

A beckoning out the cold, windy night

A rainbow promising nothing

And a warning that that nothing

Is serious business

Square business, indeed. It was just a few years earlier that James Baldwin had reminded readers, “God gave Noah the rainbow sign / No more water, the fire next time.” Capital, not God, raised the golden arches to heaven, spanning the babel of international consumption. The descending poet knew “That nothing was bringing me back / Back to de Plantation.” Home on the plantation people don’t ask about Vietnam; they ask, “Did you by lucky chance / Buy a camera a stereo deck.” These were the icons of conquest our vets were expected to bring back with them. The golden arches, in their ubiquity, signal something else about being an envoy. The Beach Boys, in the chorus to “Surfin’ U.S.A.,” mine a mystical paradox: “Inside, Outside U.S.A.” The war in Vietnam was about, among other things, what was termed in those days “spheres of influence.” A poet who knew enough to come in out of the Cold War would know the difficulty of discerning just where the American sphere begins and ends. Inside, Outside U.S.A.—not your grandfather’s double consciousness, as Thomas would observe.