Читать книгу This One Looks Like a Boy - Lorimer Shenher - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

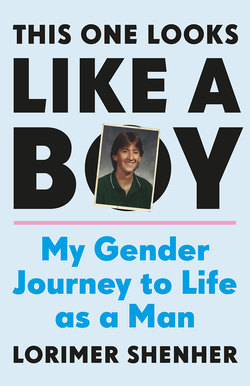

THIS ONE LOOKS LIKE A BOY

(1969–1974)

MY PATERNAL GRANDMOTHER—a stout, first-generation German Canadian woman, mother of seven, and the widow of Grandpa Shenher—would gesture at me and say to whoever was in earshot, “This one! Look at this one!” as if I were some strange two-headed fish she’d pulled off the line. “This one looks like a boy.” She always said it as if I were a museum piece, a questionable stone sculpture, unable to hear, and I would think to myself, See? Even she can see it! What the hell is wrong with this world? She has about thirty grandchildren; she knows a thing or two.

My parents, brother, sister, aunts, uncles, and cousins uniformly ignored my Grandma’s outbursts, as they would a loud fart in a church service. She was lucid and alert in those days, but no one validated her words or the truth I knew she spoke, skipping past them like a flat stone on a still lake, moving on to other topics. Everyone heard. No one stopped what they were doing or saying and I have no memory of anyone meeting my eyes when she said these things. We all just moved on, pressed the lid back down over the boiling pot. That she saw something in me—this thing I sensed about myself—both validated and infuriated me. Since that moment back in kindergarten, I had sought out ways to distract myself from my secret struggle—knowing I was a boy, but living as a girl. The constant stress was a chronic condition, my “cross to bear,” as my sixth-grade teacher Mrs. Brassard used to say about every challenge my peers and I encountered in class. As crosses went, this one was a doozy.

What made me like this? I often asked myself. While my gender journey likely began while I grew in the womb, my birth was otherwise unremarkable, according to my parents. Growing up, I had no idea that psychologists were debating how to classify and treat people like me. It would be years before the diagnosis “gender identity disorder” was added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and decades before the 2013 DSM-5 changed this diagnosis to “gender dysphoria,” defined as the “marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and assigned gender.” Both incongruence and distress must be present. People continue to debate whether a diagnosis of mental illness should be required in order to receive medically necessary health care, not to mention legal and human rights protections.

What I did know was that I’d emerged at birth looking like an average female infant. I’m sure everyone assumed I would grow up without giving my gender a second thought, let alone entertaining the mental gymnastics of nature versus nurture to try to explain how or why I was like this.

I’ll leave the debate over why people like me feel that our birth-assigned gender is incorrect to the geneticists, endocrinologists, psychiatrists, and developmental psychologists and say only this: there has not been one waking moment since that day in kindergarten that I haven’t felt an all-encompassing, deep, intrinsic sense that I am male. I also would have given anything, anything, for this not to have been so—until I finally gave in and transitioned.

WHEN I WAS six, Dad took a paid sabbatical to attend the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana, and pursue a master’s degree in Religious Studies. We rented our Calgary house out to a group of young teachers, packed up the car, and drove south across the United States to our temporary new home: a large old three-story house with an expansive yard filled with huge trees. Beyond the long backyard was a steep embankment, on top of which ran a train track. Early in the morning and late at night every single day, a train rumbled past our home, waking poor Mom each time. On the other side of the tracks, quite literally, was the area of town where less fortunate whites and a sizeable black population lived. We were strictly forbidden to go there and were never told why.

Home to the famed Notre Dame Fighting Irish football team, coached by the legendary Ara Parseghian, South Bend was a football-mad town and Dad—a sports fan who’d taken us to Calgary Stampeders games all through our youth—had a line on tickets. He took Jake and me, then aged seven and six, to several games that autumn, including the much-anticipated match against perennial rival Michigan State.

The game began with a successful touchdown drive by the Irish that sent the capacity crowd into paroxysms of glee. As Jake and I jumped up and down in celebration, I felt hands wrap my waist and lift me high into the air, across the tops of heads, over the crowd. Long before crowd-surfing or mosh pits became common, the fans of Notre Dame Stadium had a tradition of lifting people into the air and passing them handover-hand above the crowd. Just as I was losing sight of my family and beginning to feel afraid, I felt a hand firmly grasp my ankle, pulling me back. Without a word, Dad gripped my waist and placed me back down beside him in the stands, but I caught him nod and cross himself in the direction of Touchdown Jesus, the larger-than-life mural painted on the side of the campus’s main library building visible beyond one end of the field.

Every morning during the 1971–72 school year, I paused to take in the imposing facade of Thomas Jefferson Elementary in South Bend before walking up the steps and entering my second-grade classroom, unaware that my school was embroiled in a desegregation battle between the US Department of Justice and public schools in Indiana. That August, Indiana Public Schools had been found guilty in federal court of practicing racial segregation. My school was desegregated for the first time that school year, and many opposed it vehemently. I was only aware of its effect on my friendships with Cedric and Ramona, two black kids in my class, because no one seemed to want us to spend time together.

Our teacher, Mrs. Gruber, worked diligently to separate us, even when we tried to team up for group work in the classroom. She repeatedly concocted reasons for why this wasn’t acceptable—the three of us weren’t close enough in height, we needed to be all girls or all boys, we needed to make friends with other kids “like us,” we needed to be at the same reading level. It went on and on. None of the groups Mrs. Gruber formed mixed black kids with white kids. I sensed she didn’t like me; more than once she had referred to me as a “troublemaker.”

One morning after recess, Cedric, Ramona, and I ran into the classroom laughing, talking about the basketball game we’d just played. A few days earlier, Mrs. Gruber had placed our desks in side-by-side rows instead of traditional columns, and the novelty hadn’t worn off yet. I ran in front of the desks, then vaulted over mine to sit down instead of taking the few extra steps to circle around the row. She descended on me like a lion on a hyena, wooden yardstick in hand. She wrenched me by the collar to the front of the row, bent me over, and shoved my face into my desk. She screamed out to everyone, “Class! This is what will happen if you don’t obey instructions, if you don’t stay in your places!” She swung the yardstick like a baseball bat, hitting me on the backside with her full weight behind it. Whack! Whack! Whack! Whack! I lost track of the number of hits. I heard gasps from my classmates. I fought not to cry out or show her how much it hurt. I distracted myself by wondering how a woman so old and spindly could move so fast.

“That!” Whack! “Was!” Whack! “The!” Whack! “Most!” Whack! “Unladylike!” Whack! “Display!” Whack! “I!” Whack! “Have!” Whack! “Ever!” Whack! “Seen!” Whack! “In!” Whack! “All!” Whack! “My!” Whack! “Years!” Whack! “Of!” I braced for the next strike, but she paused. I waited for a Whack! “Teaching!” or Whack! “Beating Children!” The tension mounted.

“What are you doing?!” she finally screamed. I assumed she was talking to me and I dared not move or talk. The answer seemed obvious. I’m letting you beat the poop out of me, Mrs. Gruber. But then, a small voice spoke up. I recognized it as Ramona’s.

“Nothing, Mrs. Gruber.” I peeked up and saw Ramona standing at the door.

“Where do you think you’re going?! You get back in your seat! NOW!” As Mrs. Gruber banged the yardstick down hard on the desk beside me and I jumped, I saw Ramona disappear out the door. Splinters of wood flew around us, which only angered her more. She yanked me up by my collar and addressed me. “You! Get back in your seat! If you ever do anything like that again, you will see much worse than this! I don’t know how they do things in Canada, but your behavior is unacceptable!” I bit my lip and limped to my desk, tears leaking from the corners of my eyes. Jolts of electricity shot down my legs and up my back as I sat down on my bruised rear end and upper legs.

At home that night, I told my parents that Mrs. Gruber had hit me with a yardstick, but I didn’t mention how hard or how many times, or show my welts and bruises.

“What did you do?” Dad asked.

“I jumped over my desk.”

“Had she told you not to do that?”

“I guess so,” I said, uncertain.

“Well, then, I guess you had it coming, didn’t you?”

Dad hated the corporal punishment required by his job as a school principal, but in an era where hitting was condoned as necessary for proper discipline, he was expected to mete it out to students who disobeyed. His school board used a heavy rubber strap, about twice as wide as a typical ruler. At home, my siblings and I were spanked with a bare hand occasionally, and my parents trusted our teachers to dole out whatever punishment they deemed appropriate.

We never saw Ramona at school again after that day. We were all too terrified to ask why.

BACK IN CALGARY the following summer, our neighbors and friends eagerly waited for us as we pulled up in front of our house after our American adventure. Barbecues lit and beer cases in hand, they greeted us with a block party, welcoming us back home. We settled back into our relationships with friends; we were a year older, but little else had changed.

“You have to be Mary!” Corrine insisted to me. “Katherine’s Laura, I’m Ma, and Melanie’s always Nellie.” The other girls stood around her, nodding in reluctant agreement to her casting for our version of Little House on the Prairie. Corrine was bossy and always organized our basement play. Disagreeing with her never went well for anyone. I felt she miscast herself as Ma. She was definitely a busybody Nellie Oleson.

“I’m Almanzo or I’m not playing,” I demanded, arms folded, determined to play Laura’s husband.

“Fine.” Corrine threw up her hands. “We do need an Almanzo, but it’d be better with a real boy.”

Melanie spoke up. “Lori’s a good boy—she’s good at it,” she offered.

“Fine.” Corrine moved to the blackboard and handed “Laura” some chalk. “Let’s start with a lesson. Laura can be teaching us.”

“This is dumb,” I said. “Laura doesn’t teach us, she teaches younger kids.” I took off the brown vest and Dad’s oversized work boots. “I’m going outside.” I escaped up the stairs to find Jake—I felt more like I belonged when I played with him and our boy friends.

Since our return from South Bend, I’d begun to notice the group dynamics between the girls and the boys on our block. My neighbors Corrine and Melanie formed a tight group along with Katherine, each of them being no more than two years apart. Melanie was my age and we sometimes played together one-on-one, but if Corrine, Melanie, and I played together it seemed to spark conflict. I suspected Corrine was the cause, because when Jake and I got together with Corrine’s older brother Jason, who was Jake’s age, we spent hours together and no one ever fought, argued, or ran home crying.

I didn’t understand it. I wished the girls would play sports recreationally, outside of the organized girls’ leagues that existed for soccer, softball, and hockey. I didn’t think deeply on the reasons behind it in those days; it simply seemed like the girls wanted something else, and I didn’t know what it was or grasp that anyone could find play centered around sports lacking in any way.

Sports beckoned to me, and Jake was my willing partner. I was the Bernie Parent to his Bobby Clarke, the Jerry Rice to his Joe Montana, the pilot to his brakeman on our tobogganing adventures. We built our own skateboard decks, experimenting with different designs for a skiing-inspired course of skateboard slalom, an alternative to the half-pipe and freestyle events most skaters were doing. We took the bus across the city weekly with the boys from our street to ride the new skate park in an industrial warehouse run by a bunch of Dogtown wannabes.

As teens, we skied the notorious vertical drop of Mount Norquay’s North American run until our legs turned to rubber and our woolens hung on us, soaked in sweat. We took over Dad’s basement workshop each winter to tape our hockey sticks, sharpen our ski edges, drip PTEX into the gouges in their bases, and read Ski Magazine together as we glanced at the sky for any signs of snow. Ours was an easy partnership, free of the bickering and fights common among siblings. Jake was a gentle kid, much like our father; I was the feisty one, prone to more outward expressions of anger and frustration from which he would often talk me down. He never laid a hand on me aggressively or angrily.

The only physical confrontation I can remember between us as kids was when I punched him in the stomach, for reasons I can’t recall. What I do remember was the ease with which his thin belly absorbed my fist and the mixture of shock, disappointment, and sadness on his face. I recall wondering at how he conveyed all those emotions to me in that briefest of instants. The idea that I could cause another person pain or hurt seemed unfathomable to me, yet here was my best friend—my brother—and I had hurt him. Years later, when I was twenty-five and trying to convey my gender struggle to my parents and siblings, he would tell me, “You’re ruining our family.” Only then would I understand how he must have felt that day years before when I punched him for no good reason.

We lived across the street from Clem Gardner Elementary School but attended St. Leo’s, a Catholic school a few blocks away. Occasionally, we had days off that the Clem Gardner kids didn’t share. On one such sunny, winter afternoon, Jake and I—no older than eight and seven—took to the front yard for a little tobogganing. We raced up and down the twenty-five-foot slope leading down to the sidewalk. To call it a hill was way beyond generous, but we piloted our thirty-inch-round red Super Saucers—disc-shaped plastic sleds—down the slight grade like it was the Matterhorn. Mom was inside with Katherine, now four.

On one successful ride, Jake slid onto the sidewalk just as a boy about his age was walking past on his way home from school, forcing him off the sidewalk to avoid getting hit. Jake stood up beside his saucer.

“Sorry,” he said as he made his way back to our yard.

“Don’t be such an egghead, stupid!” the boy shouted, spitting on the snow near Jake’s boot. “Ya stupidhead!” Jake considered him briefly before passively continuing back to the top of the slope. I had watched the scene unfold from a few yards away, outrage growing in me like a tidal wave. Without any thought, I flipped my saucer upside down, drew my arm back in a Frisbee-tossing motion, and flung the disc with all my might. It dipped and weaved like a surface-to-air missile, the saucer’s edge catching the boy right on the side of the head above the ear, taking his wool hat with it. He dropped like a shot moose, silent for several tense moments. Jake and I looked at each other in horror, then back at the boy. Suddenly, he bounced back to his feet, staring wild-eyed at me in stunned silence before tipping his head back and opening his mouth to emit a loud, cartoonish wail. I half-expected to see WAAAAAAAAAAAH! trailing behind him in the air. He turned on his heel, hat still in the gutter, broke into a sprint, and ran away up the street, shouting, “MOMMMMMMMMMMM!” which we heard long after he’d vanished from our sight. Jake set his saucer down, climbed aboard, and slid down the slope. I did the same, neither of us mentioning what had happened.

WE HARDLY SAW Dad during the week, except very early in the morning and late at the end of the day, when he’d walk in the door, still nattily dressed in a dark suit and tie after a long day of school or school board meetings.

His weekend clothes in those years were work wear, suited to a construction site, not any office or golf course. The scent of campfire, fermented grapes, and freshly cut lumber emanated from my father’s ubiquitous green sweater; an olfactory roadmap of weekends and summers past. I don’t remember my mother ever washing it, but it never smelled of sweat or anything foul—just Dad, his projects, and maybe a hint of Old Spice. On Sunday afternoons, to help him morph back into his Clark Kent persona as a school principal, I polished his dress shoes—several black pairs and one brown—for which I was rewarded twenty-five cents a pair. The feeling of the small silver toggle between my index finger and thumb remains with me, juggling the circular metal cap bearing the kiwi logo to just the right position for snapping the can closed, preserving the moisture for the next week. Shoe polish and that sweater; the building blocks of my dad. Hard work intertwined with and fueled by a love of detail, whether it be building a home, teaching high school calculus, or making wine.

As a youngster, I followed him around on weekends and during summers to auctions, lumber yards, his out-of-town garden plot, paint stores—whatever grand project he undertook beckoned my preteen self along to simply bask in his seemingly boundless knowledge and patience. At lunch, I would marvel at his hand, where there would have appeared a fresh cut that had been absent at breakfast. His hands mesmerized me: large, strong, and callused, but with the delicate fingers of a surgeon. Sometimes I would ask him how he got injured. He’d glance at the wound, noticing it for the first time.

“Oh, look at that. I must’ve caught it on something,” he’d say, putting the cut to his mouth to clean the blood before returning to his sandwich. Whenever the wounds were mine, he’d have a look, find me a Band-Aid if necessary, then ruffle my hair or chuck me on the chin, telling me, “It’ll be all gone by the time you get married.” In early years, I’d laugh along with him at the absurdity of a kid my age ever getting hitched. As I grew older, he’d say the same thing when we’d roof together and I’d wince from the blisters on my shoulders, made by carrying loads of shingles up the ladder. His words about recovering before my wedding—intended to comfort me—would burden me with a sadness I couldn’t understand the source of, a sense that I wouldn’t be worthy of marrying, despite Dad speaking as though I was the most eligible girl in the world. In his eyes, why wouldn’t I be? In his eyes, all of my injuries could be fixed by a kiss and a Band-Aid.

He’d begun studying at the University of Saskatchewan after high school with the goal of becoming a doctor. It wasn’t until his funeral, many decades later, that I would learn that his father and mother disagreed about him continuing his studies; Grandpa Shenher wanted him to remain on the family farm, but my grandmother put her foot down and insisted Dad be permitted to pursue an education. Dad had three older brothers and Grandma Shenher argued they were more than capable—well, two of them were, and the eldest, a dedicated drinker and layabout, could be whipped into shape—and so it was that my dad became the only one in his family to obtain a university degree.

He’d hoped, after completing his undergraduate studies, to work for a few years as a teacher and save the money necessary to return to medical school, but he never did. While he did become a fine math teacher and school administrator, his talented hands never graced the medical profession, though he did put them to good use in woodworking and carpentry projects. I have no memory of him expressing regret about this or anything else in his life.

In Dad’s world, you did what you needed to do without complaint and without thinking of yourself. A man did what was necessary to make a living, to feed his family, to support his kids, to serve his God. The idea of Dad having a midlife crisis or leaving us to pursue a life unlived seemed as ludicrous as him becoming an exotic dancer. He was quietly dutiful, never resentful, always generous, and happiest among family, students, and friends.

I’d watch his hands grip a metal razor and twist the handle, until—like magic—the top would open like a flower blooming, exposing the flat, double-edged blade inside. Deftly, he’d reach in and remove the old blade, replacing it with a new one without ever cutting his fingers. His face was another story, however.

Before the days when shaving cream came in aerosol cans, he would add some hot water to a little bowl, then whisk his shaving brush around it until a thick lather formed. Dunking the brush in, he’d reach over and dab it liberally on both of my cheeks. I knew what to do next. With three fingers together, I’d rub it around my face and neck, upper lip, and chin, sneaking peeks at him beside me doing the same, making sure I was getting it right. He would always take the last bit on the end of his brush and dab it onto the tip of my nose.

I’d try my best to mimic the upside-down U shape his mouth would make as he shaved his upper lip under his nose. I would use a wooden Popsicle stick as my razor, so I never had to dampen little scraps of toilet paper and dab them onto nicks the way he would when he cut himself, which was frequently. Even so, I’d imitate that, too, wanting to mirror the entire ritual as closely as possible. I’d scrape down on my face and up on my neck, just as he did, then take a washcloth and wet it thoroughly with warm water, rubbing it all over my face to remove the excess cream. My favorite step came last: clapping a splash of Hai Karate aftershave together in my hands before slapping both cheeks gently with it and emitting a satisfied “Ah,” just as Dad did when he finished.

As I grew, I tried to copy everything he did—subtle mannerisms, how he held a hammer, the way he bit his lip when measuring a piece of wood—careful not to appear obvious. He possessed one habit I couldn’t bear: smoking. His smoking was the one thing we could complain about that would get a rise out of him, as though it represented the only harmless indulgence he allowed himself that wouldn’t interfere with being a good husband and father.

I can’t think of anything else he did that we complained about, except his bad jokes. But on summer vacations, bombing down the highway in our ’65 Valiant, his cigarette ashes blowing into the back seat from the driver’s window, I found the one trait of his I never wanted to emulate. As a kid with allergies likely caused by the “cancer sticks,” I hated it.

I imagined myself as a man who would not smoke.