Читать книгу Lessons on Rousseau - Louis Althusser - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеEDITOR’S INTRODUCTION

TO TALK ABOUT A PHILOSOPHER who explains another philosopher is a paradoxical enterprise. Should one explain an explanation?

There should thus be no mistake about the objective of this introduction. Those who know Rousseau’s texts well enough can read Althusser’s course directly, and the same holds for those familiar with Althusser’s thought.

The present introductory notes are meant for readers who are curious and attentive, but are not specialists, know the one philosopher and the other only by way of a few quotations or by hearsay, and might be discouraged by the rather abstract nature of the course or wearied by its repetitive features, forgetting that what is involved is a course intended for students taking notes, not a lecture intended for a public interested in acquiring information quickly. We have therefore extracted a few basic themes from the course, a few noteworthy original ideas, in order to provide a guide to a reading of it with the help of a few signposts, a few words, expressions and arguments that we have thrown into relief.

We have also attempted to reassess these remarks on Rousseau – which seemed remote, at the time, from Althusser’s preoccupations with Marxism – by setting them in relation to his posthumous texts. Talking about Rousseau, Althusser was also talking to himself – as a reading, forty years later, of the pages on the ‘materialism of the encounter’ shows.

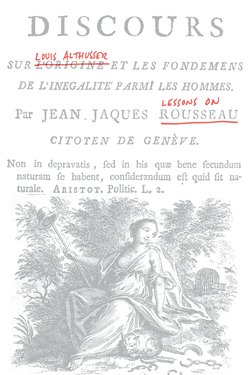

In these three lectures delivered in 1972, Althusser sets out to explicate a well-known text, Rousseau’s Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality among Men,1 a text elucidated many times before him. He proposes to analyse the ‘less current’ aspects of the text, for, he says, the history of philosophy ‘has left these aspects aside’ in ‘drawing up its accounts’ or ‘settling its accounts’.

Rousseau’s text

Rousseau’s Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, as its title indicates, examines inequality, that is, political and social life, by setting out from the origin, that is, the period preceding the advent of society, in order to follow society’s emergence and development with reference to this origin. This was a well-worn subject in the eighteenth century, in what was known as ‘natural law philosophy’ or, again, the ‘philosophy of the Enlightenment’. Philosophers go back to the origin, before society, in the ‘state of nature’, and, on the basis of a discussion of this first state, they explain why society came into existence: since this state is not viable, since men kill each other in it (that is the ‘state of war’), they have to leave it by agreeing to abolish the freedom to do what one likes and by making laws and choosing leaders to enforce them (that is the ‘social contract’). Hobbes and Locke after him produced two different scenarios from this common stock, but this theoretical configuration (state of nature/state of war/social contract) forms the absolute horizon of Enlightenment thought: every philosopher, including Rousseau, thinks within this model. Many different scholarly works (notably those by Robert Derathé2 and Jean Starobinski3) have shown Rousseau’s differences and borrowings from his predecessors; some scholars, surprised to see so many similarities between Rousseau and the others, had come to the conclusion that Rousseau is not at all original from a theoretical standpoint, and that his originality stems from the political uses he makes of theories in general circulation.4 In his course, Althusser proposes to bring out the radical originality of Rousseau, who thought in the philosophy of the Enlightenment and against this philosophy, on the basis of a completely unprecedented philosophical dispositive. We shall see that Althusser does not study the usual ‘Rousseauesque’ questions (natural law, original goodness, the critique of different forms of despotism, and so on), but directs his attention to ‘less concrete aspects’ of Rousseau’s thought.

Before approaching Althusser’s lesson, let us take a look at the way Rousseau’s Discourse on the Origin of Inequality presents itself. This text – often called the ‘second Discourse’ because it was preceded by the ‘Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts’ – has two parts. The first runs from the origin to the eve of society; the second treats the establishment of society beginning with the emergence of property. (‘The true founder of civil society was the first man who … thought of saying, “This is mine.”’5) In his course, Althusser basically discusses Part I, the pages in which Rousseau describes the origin before society (‘the state of pure nature’). Here, Rousseau criticizes his predecessors for bungling this question: these philosophers ascribed to men in this supposedly natural state traits that are social, not natural (language, reason, property, the sense of honour, and so on), presupposing interhuman relations that were already social (aggressiveness, mutual assistance). In short, they put society in nature: ‘they talk of savage man and they paint civilized man’.6 One must, then, avoid this mistake and ‘dig down to the roots’7 in order to describe a genuinely natural state, with men who are simply a sort of animal; they live scattered, without relations, without language or reason, and so on: men who roam all alone through the forest and sleep three-quarters of the time. Rousseau’s text presents itself as a narrative, a sort of fictional vision that describes original man (Rousseau’s famous ‘good savage’, who is so frequently evoked): a man living in solitude, peaceful, robust and naive, savouring a childish happiness; a sort of Eden that was to become the object of a celebrated gibe of Voltaire’s, who felt the sudden urge ‘to go on all fours’ after reading the book. The Discourse on the Origin of Inequality quotes only a few authors and seems to want to avoid philosophical speculation.8 Its descriptive style and simple diction have given rise to the idea of a visionary, utopian, romantic Rousseau, and it is classified more often as ‘literature’ than as ‘philosophy’ in school and college curricula.

The second part of the Discourse explains that this state of ‘infancy’ could well have gone on forever, but that natural catastrophes, accidents, modified this first life, which became impossible (because of climatic change, the increasing scarcity of foodstuffs, and so on). Men were forced to gather in groups (families, villages, huts) and they forged connections with each other (to hunt big game, for example). This new life engendered new feelings: self-esteem (how others see me), imagination, reason. This second epoch, which Rousseau calls the ‘youth of the world’, is a first step beyond nature, a step, but just a step, and it would have been possible to remain there too for ever; things were not so bad that they had to be changed.9 A ‘fatal accident’,10 however, opened the third period: thanks to some chance occurrence (perhaps the eruption of a volcano), men discovered metallurgy, and the domestication of fire enabled them to clear land and invent agriculture; this led to a sort of system of economic exchange (a division of labour between metallurgists and farmers), a system that lasted as long as there was still land to be cleared.

The next section of the Discourse is about the origin of property, starting with the moment when all the available land had been cleared: some people (the ‘rich’) owned land, while others (the ‘poor’) owned nothing. At this point, a state of war began, for the poor sought to seize land for themselves, until the rich proposed a contract that put an end to the war and allowed them to keep their wealth: this is how inequality among men originated. There follows a description of political life, its corruption and slide towards tyranny. Althusser does not, however, analyse these pages in his course, confining himself to a few remarks about the return of the origin (state of nature) at the end of the process (the descent into tyranny).

As we have already said, Rousseau’s text resembles a narrative, almost a novel, of human history;11 an imaginary panorama inspired by travel narratives (the remote savages of the islands) and rounded off by Buffon’s observations (Rousseau refers to Buffon in numerous notes): ‘I see an animal less strong than some … I see him eating his fill under an oak tree, quenching his thirst at the first stream … What is true of animals in general is, according to the reports of explorers, true of most savage peoples as well.’12

Althusser’s course

Althusser’s course is not about the ‘basic concepts’ of Rousseauism, that is to say, natural law, human nature, food (fruit or meat), health, goodness, self-esteem, property, and so on.13 Althusser takes up a problem in the margins of these concepts: that of the unfolding of history, that of the transition from one period to the next, from a present moment to its future. He treats the Discourse on the Origin of Inequality not as a narrative, but as a conceptual progression, a series of novel philosophical problems in search of solutions never before proposed. He presents the text as a series of links in a chain, commanded by what Rousseau posits at the outset: the true origin, ‘the root’, ‘pure nature’. He goes on to show how each textual detail is a theoretical response to problems generated by this theory itself; what seemed to us to be mere stage decorations, mises en scène, or dramatis personae reveal themselves to be, as Althusser reads them, veritable philosophical concepts. There we have Althusser’s ‘signature’, his distinctive trademark: he ‘flushes out’ concepts the way a hunter flushes out game and fashions new concepts in order to insert the theories that he establishes in them.

His three lectures break down as follows: the first is about the origin of society, the second examines the genesis of society, while the third returns to the state of origin and explains its coherence in detail.

What is striking about this approach to the text is that, far from presenting Rousseau’s positions – his ‘ideas’, as one says – Althusser trains our attention on the problem commanding them, drawing out the distance between the problem and its solution as far as is possible and displaying all the threads which separate them, tautened to the snapping point. Rousseau, to repeat, criticizes his predecessors on the grounds that their ‘origin’ is already social and that they have not attained the true origin. With this as his starting point, Althusser examines Rousseau’s text to show that his critique of other philosophers is posed in terms such that we can no longer see how he can avoid the mistake for which he criticizes others: for he criticizes them for making a mistake while simultaneously showing that this mistake was inevitable! Thus Rousseau calls the use of reason into question, for reason is not natural but social and is therefore incapable of grasping the state of nature. Yet philosophy has no tool other than reason with which to think anything at all, and if reason is invalidated, it is hard to see how it could conceive of something that excludes it for essential reasons. No one can draw a straight line with a skewed ruler, not even the person who denounces the warp in the tool. Philosophy is caught, Althusser says, ‘in the circle of denaturation’, from which it is impossible to get out of with our faculties (reason, imagination, and so on), which are themselves, as products of this denaturation, caught in this ‘circle’. How is one to free reason from this circle that produces it, in order to think outside the circle, in order to think true nature? Althusser, accordingly, presents Rousseau as caught in the trap which he set for his predecessors, but which was sprung on him: by invalidating reason itself, not just an error in reasoning, he renders himself powerless. Rousseau ‘leaves this circle by way of the inside’, Althusser explains, ‘by going back into [himself]’ and listening to ‘the voice of [his] heart’.14 Althusser wrests the Rousseauesque ‘heart’ from Romantic or intuitionist interpretations of it in order to confer epistemological status on it: it is, within denatured nature itself, the voice of nature that will be able to guide reason. The heart is not one element among others in Rousseau’s thought; it is the operative key to an impossible operation, the production of knowledge about true nature. There is more: by making reason dependent on the heart, by thus endowing it with secondary status, Rousseau ‘marks himself off from’, or ‘takes his distance’ from, the Enlightenment philosophy which posits reason as the fundamental, supreme principle. The ‘heart’ is thus not a thing – not even a deeply personal thing – but a theoretical operation, the consequence of which is a grasp of the true origin, the state of pure nature. ‘Pure’, in the expression ‘state of pure nature’, indicates – Althusser dwells on this – the difference from ‘the state of nature’ of which all the natural law philosophers speak. The ‘heart’ is a concept that operates on the object peculiar to it, and this object is ‘pure’ nature.15 Althusser’s first lecture thus situates Rousseau in his historical period and establishes the epistemological status of his concepts.

His second lecture is about the genesis of humanity, the genesis that leads to society as we know it. Here, too, Althusser sets about exacerbating problems. Once we have isolated the state of pure nature by leaving the ‘circle of denaturation’ (in which his prececessors were caught), it remains to see how, and by what means, it will be possible to turn back towards this denaturation (which has taken place; this is a fact, inasmuch as the state of pure nature no longer exists). Althusser, rather than quickly taking up the solution proffered by Rousseau (which we mentioned above: natural catastrophes, the discovery of metallurgy), subjects the state of pure nature to veritable philosophical torture in order to make it confess, by all available means, that it is incapable, radically incapable, of producing society. It is as if Rousseau, after leaving the circle of denaturation by way of the heart, found himself caught in a second ‘circle’, that of the true origin, with no way of getting out of it. After seeking to formulate a true origin that expels every disguised trace of society, Rousseau walls himself up in a ‘theoretical isolation’ from which there is no exit: between this true origin and society he puts a ‘distance’, an ‘abyss’, a ‘void created by this separation’.

That is the price to pay for this origin that is a ‘radical absence [néant] of society’. A radical absence, not just an absence, for nothing indicates its absence, in the sense in which someone who is absent is waited for, has his name on a list: there is a place for him to take, which is empty while we wait for him, yet a place we can designate nonetheless. Althusser presents the state of pure nature as a present without a future, in a radical sense: the future is not a necessity inscribed in the present (what Althusser calls a ‘deduction’ – or ‘analysis’ – ‘of essence’). We must, however, also understand that the future is just as plainly not a possibility of the present (a virtuality dependent on various elements contained in the present, which might, under certain circumstances, combine and fuse). Neither a necessity nor a possibility, the future is the impossible of the present. Historical time is thus divided, torn [écarté, écartelé] between a suspended present and ‘its’ future, from which it is absolutely separated (by an ‘abyss’).

On the basis of this hopelessly blocked situation, Althusser opposes the solutions of natural law philosophy (Hobbes, Locke) to Rousseau’s. In Hobbes and Locke, society is deduced from the state of nature, since it is already present in it and its genesis is ‘linear and continuous’; this is a ‘deduction of essence’. For Rousseau, this genesis is the very opposite of a deduction; it can only come about thanks to chance occurrences and accidents that impinge on it from outside (catastrophes). It is a genesis made up of ‘gaps’, ‘breaks’, and ‘hiatuses’. Ultimately, the state of nature finds itself ‘dismembered’ in three ‘discontinuous moments’. The closed circle of the true origin (circle 1) is succeeded by other circles that are just as hermetically sealed: the youth of the world (circle 2) and nascent agriculture (circle 3).

This presentation of Rousseau’s theory as riven by discontinuities [en déchirure] leads Althusser to define two points. The first is that Rousseau’s philosophy proceeds by way not of right, but of ‘history’, the ‘event’: there is no appeal to right emanating from a fearful humanity (as there is in Hobbes, where men prefer to be subject to laws rather than risk death). Accidental, unpredictable fact changes everything and establishes a new order. The second point bears on the theory of this history: this Rousseauesque history is a combination of the accidental and the necessary. The accidents are contingent, but arrive ‘at the right moment’: there is ‘coincidence between chance and the moment of chance’,16 and this establishes a rational, non-teleological history, because the necessity of the future has to wait for contingency. Althusser then comes back to these three ‘circles’ of the state of nature: pure nature (circle 1), youth of the world (circle 2), and metallurgy + agriculture (circle 3). If circles 2 and 3 are the result of a process, circle 1, in contrast, ‘results from nothing’ and ‘is not the beginning’, for ‘the beginning begins [ça commence] after the origin’. Thus it comes from nothing and goes nowhere, as if suspended in the ‘void’.

The rest of the second lecture examines this first state, paving the way for the following lecture, which will go into its contents in detail. Althusser puts this state under the general sign of negation: it is a ‘radical absence of society’, a ‘radical absence of natural law’, and it requires Rousseau to find a ‘representation of negation’. Althusser explains that the ‘realization’ of this ‘void’ is provided by ‘the forest’, which is ‘a void’ ‘without time’, while human qualities in this state are themselves ‘purely negative’ (such as pity), or ‘virtual’, ‘latent’ (such as reason and perfectibility). This true origin is an ‘origin of nothing’ [origine de rien]; it is not the true double of the false origin, as in Plato, for whom error (the shadows at the back of the cave) is a deformed replica of reality (the light and the ideas outside).

The future is, at every moment in this history, not just absent from the present, but annihilated by a sort of antibody. The present abounds in anti-future; it is full of an antibody that voids the future, should it, perchance, present itself. The forest is this antibody, for it stuffs savage man full of everything he could feel a need for before he feels a need for it; it is a black hole that devours all causality in advance, with the result that there is no future in preparation or even in gestation. Thus ‘perfectibility’ does not strike root in the state of nature in order to bear fruit later, in society; ‘perfectibility’ is present, but for nothing, awash in an excessive fullness that drains it of all reality. We can learn only after the fact that it was present.17 One measures the difference in tone between Rousseau’s narrative, which is focused on savage man, his life, his acts, and his encounters, and Althusser’s reading, which invests it with concepts and lines of force, a reading that is quite remote from the apparent ‘novel’.

The remainder of the genesis, phases 2 and 3, is thus external to this ‘origin of nothing’, and the ‘law of development’ is specific to each phase, operating within each ‘particular’ circle. Each circle invents its own logic, fabricating its internal laws and problems for itself; they are not the same as those of the preceding or following circles (for example, the origin of language is a problem that arises in the state of pure nature, but not in the youth of the world, while there is no place in the latter for the economic questions of labour, wealth, and so on, which will be at the centre of the next circle). Thus, according to Althusser, no general laws of history exist for Rousseau, but only regional laws that belong to each particular moment of history and yield to other laws in subsequent periods. We are at a very far remove from a Rousseau supposed to have anticipated Marxism with its universal economic laws (productive forces, relations of production, and so on).18

At the end of these three states of nature, the social contract makes its appearance. It is a ‘leap in the void’, suspended over an ‘abyss’, and a ‘new beginning of the origin’, a ‘negation of the negation’ (‘denaturation of the denaturation’). For the social contract denatures man, but the man in question is the man of state 2 and state 3. These states, however, are themselves denaturations of state 1. Thus we do indeed have a denaturation of the denaturation.

The third lecture is more concrete: Althusser serves us notice that he intends to carry out a reading of the text itself, in order to analyse in detail that which makes it possible to think the state of pure nature. This state concerns, first of all, man’s relation to nature, and, second, men’s relations to each other. The former (man–nature) is an ‘immediate’ relation; ‘man is at home’ in nature because nature meets all his needs at all times and in all places. The latter (man–man) is ‘nugatory’, ‘nil’ [néant]; men live in dispersion, without contact, never seeing each other twice and forgetting each other as soon as they see each other. These relations make the state of pure nature possible, but are they themselves possible? That has to be demonstrated.

This demonstration implies a particular theoretical operation, for, says Althusser, to understand this Rousseauesque dispositive, we have to bring out certain concepts which are not ‘thought’ by Rousseau, although they are ‘practised’ by him; which are present in Rousseau, but in a state of ‘theoretical divagation’. We must therefore go to work to pin them down and make them plainly visible, for Rousseau ‘does not see them’, he ‘directs his gaze elsewhere’, they ‘escape his attention’. This holds for the concept of the ‘accident’, which is stated but not analysed as such; it holds, above all, for the ‘concept of the forest’, which is central: without it, the origin is unthinkable. Althusser replaces Rousseau’s gaze, ‘directed elsewhere’, with another that makes it possible to see that the forest invented by Rousseau basically fulfils all the conditions required for the immediate fusion of man with nature (trees with low branches laden with fruit; shade; refuge), and also to see how the same forest separates men from each other (assistance is pointless, for the forest provides everything; war is impossible, for the forest offers protection and abundant nourishment). Setting out from this conceptual mise en scène, Althusser puts the elements of the theory back in place, bringing out its points of opposition to other theories (Hobbes, Pufendorf, Diderot, but also Aristotle). In this sense, his third lecture will seem more familiar to readers who know Rousseau; they will find a Rousseau they know in it, albeit displaced, highlighted, and redistributed.

Concepts at work

We must now go back over this description of Althusser’s course in order to emphasize a certain aspects of it. First of all, the reader who reads through the Discourse on the Origin of Inequality before reading Althusser cannot help but notice one thing: certain terms that Althusser uses are unmistakably Rousseau’s, and here Althusser works on the standard text (for example, state of pure nature, pity, youth of the world, forest, needs, and so on); whereas other terms – terms that recur insistently throughout his exposition – are completely absent from the Discourse on the Origin of Inequality and even from other texts by Rousseau (for example, circle, nothingness, distance, void, negation of the negation, and so on). This remark about an obvious feature of Althusser’s text leads us to oppose two levels of reflection: explained (Rousseau’s text with its terms, the meaning of which has to be elucidated) and explaining (Althusser’s discourse, with its invented terms that serve as tools with which to work on the first level). This might make it seem that we have to do here with the rather common situation of an ‘explication of the text’ that makes use of general categories to underscore the logic of an argument, along with its effects or its intentions. This way of looking at things is, however, incomplete, for in reality there are not two levels (Rousseau’s terms/Althusser’s terms), but three. Why three? Because the first level, that of ‘Rousseau’s terms’, is itself situated on two levels, leading us to distinguish three levels.

1. There are, first, the terms (in reality, concepts) that operate in a way that the text takes responsibility for; they are at the centre of Rousseau’s reflection and play an explicit theoretical role: nature, force, need, pity, perfectibility, and the like. All these concepts provide the core of the specialized studies of Rousseau.

2. There are, however, other terms (which are perhaps concepts, according to Althusser) that remain in the background to form a sort of accompaniment, prop, or punctual explanation: pure nature, the forest, accidents, and so on. Althusser says that Rousseau ‘practises’ these terms without ‘seeing’ them, because he ‘directs his gaze elsewhere’. When we read his course, we notice that the leading role has been conferred on these backgrounded terms; they are the ones that traverse Rousseau’s text in order to indicate its coherence and unity. The example of the forest is noteworthy. In Rousseau’s text, it seems to be nothing more than a stage-setting needed for the actors’ performance; it is there simply to provide decor for the life of savage man. In Althusser’s course, in contrast, the forest becomes the leading actor; it unfolds through the text’s every detail, sustaining and producing it to the point that natural man, pure nature, and so on become nothing more than the shadows of the theoretical trees and fruit of the forest that grounds the entire edifice.19

3. It seems to us that this promotion of stage-setting-concepts or character-concepts results from the intervention of the last level (circle, void, nothingness, and so on) in Rousseau’s text. It is as if this third level, rather than working on the text, slides beneath it in order to make its critical joints crack or to produce conceptual hernias: Althusser forges and uses these sub-concepts in order to display the fault-lines in the textual crust, to destroy its seeming continuity in order to set it on other foundations, on the ground of new concepts, on a new text of Rousseau’s. In fact, it is the same text, but the roles have been inverted: the stage-setting has come to occupy the foreground.

The second level of reading is what we have called the conceptual ‘promotion’ of certain figures, the ones Rousseau ‘practised’ without seeing them because his gaze was ‘directed elsewhere’. It seems to us that, at this level, Althusser has inaugurated a vast working programme for Rousseau studies, for he has shown the conceptual power of common objects (trees) or mises en scène (the non-fight under the fruit tree). Well before Gilles Deleuze put forward the notion of a ‘conceptual persona’,20 Althusser had already worked it out, allowing us to ‘see’ that the epistolary exchanges in The New Heloise are a mise en scène of the concept of virtue, that the various mises en scène in Emile are so many references to certain laws of development of human history, that feminine sexuality is bound up with the theory of history, that Jean-Jacques Rousseau himself establishes his ‘biographies’ as the last experimental mise en scène of human nature and its denaturation. Althusser has assimilated the fictional and the picturesque in Rousseau to the stark order of systematic conceptuality. Many modern readers of Rousseau owe him a great deal.21

Let us begin with the third level, which corresponds to the body of Althusser’s first lecture, the part following the introductory comparison of Machiavelli and Rousseau. What we are calling the ‘third level’ involves those concepts that are nowhere to be found in Rousseau’s text and that Althusser constantly insinuates beneath it in order to reveal its fractures and moments of crisis. The first of these concepts is the circle, which is applied in various ways: Rousseau criticizes philosophers for conflating the state of nature and the state of society by inscribing social characteristics at the heart of nature, but adds that this mistake is grounded in reason, which is itself incapable of thinking anything other than society, since reason is not natural, but social. Althusser calls this argument ‘the circle of denaturation’ or ‘alienation’. This figure of the circle goes well beyond the logical figure of the ‘vicious circle’, that is, of tautology or repetition of the same thing (A = A, social reason = society as represented by reason [la société raisonnée]).

Here, ‘circle’ indicates the absence of an outside or, to put it differently, the absence of a cause that would make it possible to leave the circle; it is an anti-Hegelian circle with no inner motor, a circle that can only go round and round for lack of an internal cause. If Althusser talks about a circle of denaturation containing a reason that is powerless to leave it, it is not in order to give a new name to the methodological tautology that Rousseau denounces, but to show the impossibility of leaving this circle – for Rousseau is trapped in his own critique and has no means of escaping it. The circle is neither a logical nor a topological figure, but a causal or, rather, anti-causal figure: Althusser uses the word ‘circle’ to designate a theoretical configuration that does not contain the causes of its own development. Every occurrence of the ‘circle’ later in his course is geared to this crisis of causality and leads to the same question: How to escape it, given that Rousseau has locked the exits without providing the keys? Thus, after the circle of denaturation which impedes the discovery of the state of nature, this state of nature, once it is mentioned by Rousseau, is described as a circle in its turn; the same holds for the state of the youth of the world and, finally, for that of metallurgy and agriculture. These three circles produce nothing but their recommencement, that is to say, nothing; each time, Althusser leaves his auditors waiting for a solution, a wait without an object, since this object, the cause they are waiting for, is not in the circle. Upon this wait, this ‘suspense’ that is a wait for no one knows what, Althusser constructs a scene of the void, of absence, of deviation, of demarcation, of distance, and even of the abyss (a term of Rousseau’s that Althusser uses in a different sense).

Comparison of the courses of 1956 and 1966 with the present course (1972)

The figure of the circle that encloses a radical absence [néant] of causality seems to make its appearance rather late in Althusser’s readings of Rousseau. In 1956, his course on Rousseau affirms, on the contrary, that he ‘conceives of history as a process, as the effect or manifestation of an immanent necessity … It is not, however … a continuous, linear development, but a nodal, dialectical process.’22 And again: ‘Rousseau is perhaps the first philosopher to have systematically conceived of the development of history … as a development that is dialectically bound up with material conditions … (consider the forest, the end of the forest, the rich and the poor …).’23

We certainly do find a circle in the 1956 course, but it is the circle of tautology.24 It appears clearly that Althusser, like most of Rousseau’s Marxist readers, is looking for an internal (‘immanent’) historical causality in the Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, a history that progresses by sudden leaps and bounds (‘dialectical nodal process’) and is grounded on a material base (‘the forest’, and so on). The portrayal of a historical time on the verge of the abyss, empty of determinations, is not yet on the agenda.

Ten years later, in the 1966 course, the circle, the void, and nothingness all make their appearance. They do not, however, have the same systematic character; they are still associated with tautological forms and dialectical genesis. Certain formulas that the 1972 course puts at the centre of its reflection are to be found in the 1966 course, as are ‘circles’ separated by ‘accidents’.25 One difference should be noted: in 1966, the internal relation between closure (circle) and the annihilation of history (the void) is not explicitly thought through; that is why, in 1966, the forest does not play the decisive role (causal antibody) that it will play six years later, in the course we are here concerned with.

Let us turn back to the 1972 course. It can be seen that the sub-concept of the circle and the sub-concepts of the void, nothingness [néant], and so on form a system: there is a causal void because the circle is a radical absence [néant] of internal causality (‘radical absence of society’). The ‘circle’ makes it possible to eliminate recourse to the ‘dialectic’. The term ‘dialectic’ is, moreover, absent from this course, except in a quotation from Engels, who finds ‘in Rousseau … a whole series of the same dialectical turns of speech as Marx used’.26

Althusser, then, isolates the ‘circles’ that turn round and round for lack of an internal cause, and it is clear that this figure is constantly associated with the ideas of negation, the void, nothing, and so on. There is nothing in the circle that could get us out of it. Althusser’s thought is fixed on a particular type of causality, the one we can neither predict nor expect nor guess, for it is an ‘accident’ – a term of Rousseau’s that he elevates to the rank of a master concept. It is likewise in order to produce the void – to show clearly that, in the circle, there exists no cause, however slight, that might make it possible to leave it – that Althusser is led to establish the forest as a concept: for the forest is perceived as the a priori suppression of anything that might open up the circle, so that there is not only nothing in the circle, but also a painstaking construction of this nothing. The forest is a ‘concept’ because it is the incessant, painstaking fabrication of this nothing; it puts, everywhere, a void between every thing and what follows that thing; it blocks every embryonic form of causality in advance.

By creating the void around the circles and in them, Althusser makes room for a theory of history at antipodes from the ‘dialectical’ tradition that depicts historical time as an unfolding of the contents, the ‘internal contradictions’, that produce their sublation. There is no contradiction in the Althusserian circles; history becomes inseparable from the idea of the event, that is, an unpredictable accident that occurs at the right moment. It would be a mistake to suppose that the passage about the ‘negation of the negation’ (‘denaturation of the denaturation’) suggests a kind of dialectic, à la Engels. For, in this passage, Althusser defines the social contract as a negation of the negation on the grounds that man’s entry into political society necessarily denatures him (Rousseau repeats this in several texts). As we noted, however, this denaturation pertains to a previous state (youth of the world, agriculture) that is itself a denaturation with respect to true (pure) nature. It is, for this reason, a denaturation of denaturation. In this formula, however, the negation of the negation, far from being the motor that goes from the present to the future (from pure nature to society), is, rather, a return of the present towards the past for the purpose of recovering that past après coup. Althusser calls this a ‘reprise’ [reprise]. Society takes back [reprend] from nature what nature never gave it. Thus there is a return of (towards) pure nature, but not at all in accordance with a dialectical spiral advancing all by itself. Quite the contrary: Althusser takes note of a return or reprise of something that was without effect, without dynamics, without progress – it is simply noted. One sees what Rousseau owes to Althusser: a reading that transforms his figures (images, characters, stage-settings, situations, and the like) into veritable concepts and a theory of history that is materialist but not dialectical.

What Althusser owes to Rousseau

In considering Althusser’s three courses on Rousseau (1956, 1966, 1972), we have seen that he gradually takes his distance from what might be called the traditional Marxist reading of Rousseau. Obviously there exist Marxist readings that are highly divergent in their interpretations, but they generally revolve around the same preoccupations. Rousseau is a ‘petty bourgeois’ thinker (a reading directly inspired by Marx), a dialectician (Engels), a socialist who anticipated Marx, and so on. Generally speaking, Marxists look for a dialectical ‘method’ in Rousseau, an economic determinism, a body of political thought centred on the state or on equality, an anthropology that opposes man and the citizen: they look for Marx in Rousseau either to find him there or to remark his absence.27 While Althusser’s 1956 text fits into this theoretical landscape rather well, his 1966 text detaches itself from it, and his 1972 text has nothing more to do with it.

In 1972, there is no longer any question of the dialectic and, as we have emphasized, the ‘negation of the negation’ is the very opposite of what Engels designates by that term, since, rather than being a future-orientated process, it is merely the retrospectively observed ‘reprise’ of an inactive past. The economic problems have disappeared, and the whole course concentrates on hermetic circles emptied of causality, the happen-stance of unpredictable accidents, and the retrospective theory of history, which breaks with the monism of laws that constituted the foundation of the historical and dialectical materialism in general circulation; it is not a question of either class struggle or productive forces (elements that are, however, easy to exhibit in Rousseau’s text when one sets out from simple identifications: the rich/the poor, forced labour, and so on). Thus Rousseau appears to be at a rather far remove from Marxism, and Professor Althusser seems oddly distant from the communist philosopher who gained his international reputation on the strength of an analysis of the writings of Marx, Lenin, and Mao.

A reading of Althusser’s posthumous texts and his correspondence shows that this is not the reality of the matter, and that, in 1972, Althusser was thinking about the question of materialist philosophy in accordance with a twofold idea.

On the one hand, he was fabricating ‘his own Marx’28 by repeating the classical terms of Marxism in order to confer new content on them. He poured new wine into old bottles, keeping the words but investing them with a meaning that allowed him to develop a new theory of historical causality.29 He rejected materialism’s ontological preoccupations (matter precedes thought, and so on) in order to found materialism on a theory of knowledge and, later, on a theory of the primacy of practice. All this is rather well known.

On the other hand, he already had this ‘Rousseauesque’ depiction of nothingness, the unpredictable encounter, circumstance, retroactive [après-coup] causality, and the like in mind, as is attested by his correspondence when, in 1971, a year before delivering this course, he wrote to his friend Franca: ‘Encounter: this word is very important for me, and has a profound resonance: I’m holding it in reserve for philosophical interventions about the dialectic that I will make some day.’30 We can also discern a few formulations of this line of thought in his lecture on Lenin: ‘The intervention of each philosophy, which displaces or modifies existing philosophical categories … is precisely the philosophical nothing … since a dividing-line is actually nothing; it is not even a line, but the emptiness of a distance taken.’31 Above all, his posthumous autobiography sheds light on this development. He evokes the ‘materialism of the encounter’ in these terms in it: ‘I typed (between November 1982 and February 1983) a two-hundred-page philosophical manuscript which I have kept … Actually, I expressed for the first time in writing a certain number of ideas I had carefully stored away in my mind for over twenty years, ideas I told no one else about as they seemed so important to me (!).’32 These important ideas are those of the materialism of the encounter, the ‘underground current’ whose resurgence he wished to reveal. He attributes it to Epicurus and Democritus, but it is Rousseau who reactivates it,33 and Althusser partially reincorporates his 1972 course into this hastily written text.

There can be no question of presenting this new philosophy here.34 We shall restrict ourselves to displaying its themes, which echo the course on Rousseau that concerns us here. A few quotations will indicate the tone of it, while bringing out the radical difference between this materialism and the (mechanistic or dialectical) materialist tradition which, as is well known, is a thought of necessity, determinism, and the laws of Being.

My intention, here, is to insist on the existence of a materialist tradition that has not been recognized by the history of philosophy. That of Democritus, Epicurus, Machiavelli, Hobbes, Rousseau (the Rousseau of the second Discourse), Marx and Heidegger, together with the categories that they defended: the void, the limit, the margin, the absence of a centre, the displacement of the centre to the margin (and vice versa), and of freedom. A materialism of the encounter, of contingency – in sum, of the aleatory.35

This philosophy is, in sum, a philosophy of the void … a philosophy which creates the philosophical void in order to endow itself with existence … philosophy’s ‘object’ par excellence is nothing, nothingness, or the void.36

This void is clearly the one that Althusser reveals in his interpretation of the theory of history in Rousseau; it is the radical absence of the future at the heart of the present, the absence of any general law that might make it possible to trace the contours of a possibility. The real is thus nothing other than the consequence of ‘accomplished facts’, of ‘encounters’, of ‘contingency’; necessity (which is so important in the schema of traditional materialism) is simply thought’s return to the absolutely unpredictable accomplished fact, which it takes up again in order to establish its necessity. The historical real invents its laws, while thought boards ‘a moving train’ and adapts to its rhythms in order to understand those laws after the fact.37

The posthumous text (‘The Underground Current’) declares its debt to Rousseau at length:38 ‘The most profound thing in Rousseau is doubtless … this vision of any possible theory of history, which thinks the contingency of necessity as an effect of the necessity of contingency, an unsettling pair of concepts … explicitly postulated in Rousseau.’39

In these pages, written in haste, we find Althusser’s 1972 Rousseau again, with, however, certain differences. In the course on Rousseau, it is the notion of the ‘circle’ which assigns the ‘void’ and ‘nothingness’ their theoretical status, for this void is the void of causality, bound up with an immobile, self-enclosed stage with no outside; the void is a confinement. In the text on the materialism of the encounter, the circle breaks open, freeing the void and nothingness, which pour out into the whole of the thinkable real, constituting not a particular figuration (state of nature, and so on), but philosophy as such. Rousseau’s theory is now shorn of its ‘circles’, which had provided it with its frame. The example of the forest is revelatory. In the 1972 course, the forest shields the circle of pure nature and puts a brake on all human evolution; in the text on the materialism of the encounter, however, it becomes a general paradigm of the void, an Epicurean void with no encounters between the atoms and no encounters between people. It had been an excessive fullness of food and an excessive fullness of shelter that ruled out the social, a natural excessive fullness that was a ‘radical absence of society’, inconceivable without the hypothesis of a pure, self-enclosed nature. In the following quotation from ‘The Underground Current’, in contrast, we see the ‘radical absence [néant] of society’ escape from the circle of pure nature, to be transformed into the ‘essence of all society’. In the course, however, this essence had not proceeded from ‘nothingness’ [néant], since this nothingness was not an ‘origin of nothing’: but, rather, from an utterly heterogeneous accident which, far from proceeding from this nothingness, put an end to it. Here is the posthumous passage on this question: ‘The forest is the equivalent of the Epicurean void in which the parallel rain of the atoms falls … In this way, Rousseau seeks to represent … a radical absence of society … the radical absence of society constitutes the essence of all society.’40

In the materialism of the encounter, there is no longer any room for the circle, and Althusser seems to abandon this figure, which constitutes the topological basis for his course.41 We find it again, by chance, in his autobiographical narrative, when he discusses his experience of captivity in Germany: just as Rousseau leaves the circle of denaturation by way of the inside (the heart), the prisoner-of-war had thought up a plan to escape by hiding in the very heart of the camp.42

More seriously, in ‘Is it Simple to Be a Marxist in Philosophy?’, Althusser criticizes the notion of the circle, which he considers to be too Hegelian to suit materialism: ‘a circle is closed, and the corresponding notion of totality presupposes that one can grasp all the phenomena, exhaustively, and then reassemble them within the simple unity of its centre’.43

In contrast, the theme of the multiple laws of history specific to each period is forcefully taken up again, with its theoretical complement (already present in the course) of retroaction [l’aprèscoup]: ‘No determination … can be assigned [otherwise] than by working backwards from the result to its becoming, in its retroaction … we must think necessity as the becoming-necessary of the encounter of contingencies … every historical period has its laws.’44

Thus each of the sub-concepts that allow Althusser to reveal the neglected fabric (Rousseau directs his gaze elsewhere) of Rousseau’s theory derive from these ideas that he had in mind but confided to no one. They allow him to construct ‘his Rousseau’,45 just as he constructed a Marx all his own. Rousseau is an experimental field from which he makes nothingness, the encounter, retroaction, and so on surge up: so many non-Rousseauesque categories that nevertheless fit Rousseau to perfection: ‘It is to the author of the second Discourse … that we owe another reprise of the “materialism of the encounter”.’46

The word is, unmistakably, reprise, which plainly means that it is a question of a retroactive encounter, not a continuity. Rousseau took up the materialism of the encounter in the sense in which the materialism of the encounter took up Rousseau, thereby opening up a field of reading that is still largely unexplored.

Yves Vargas, May 2012