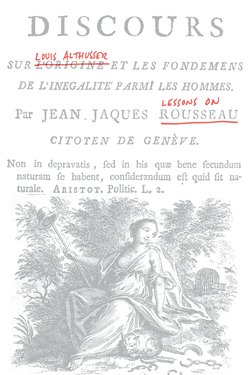

Читать книгу Lessons on Rousseau - Louis Althusser - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеLECTURE ONE

25 February 1972

LAST TIME, I ANNOUNCED THAT I was planning to give you a lecture, or a few lectures, on the conception of law [droit] and politics in Spinoza. In reading up a little on the question, however, I discovered that an excellent work on it has been out for several months now: Matheron’s doctoral thesis, Individu et communauté chez Spinoza.1 If I were to take on this question, I wouldn’t do much more than reproduce, basically, what Matheron has written. That’s why I thought it would be more helpful to talk to you about another subject, another author, and to submit a few, less common, reflections on Rousseau to you.

Changing programmes is, obviously, a high-handed procedure. Please accept my apologies, but I didn’t have much choice: I’m not as competent as all that. I can really only talk about subjects I know at least a little and, for many authors, that is not the case. It is the case, somewhat, for Rousseau. So, after talking to you about Machiavelli, I shall try to talk to you a little about Rousseau.

To talk about Rousseau after talking about Machiavelli is not just to change periods, since it means crossing two centuries of history and, in particular, two centuries of natural law philosophy, but it is also to change worlds. It is a matter not just of changing historical worlds, but of changing theoretical worlds too – of changing, quite precisely, the object of reflection and, still more, the form of reflection, the form of thought, the modality of thought. From that standpoint, in order to bring out these differences, however paradoxical the idea may seem, it is perhaps not without interest to compare Machiavelli’s world in thought to the natural law philosophers’ and Rousseau’s.

I think we can regard the following condition as determinant and as a distinguishing criterion: what is at issue, what is at stake and in question in Machiavelli as well as the natural law theorists is absolute monarchy as a form of realization of the nascent and the developed bourgeois nation – and thus as an objective referent common to their different histories. In Machiavelli, however, that same historical referent plays a role altogether incommensurable with its role in the natural law theorists. That is what makes their theoretical worlds different; for the absolute monarchy does not occupy the same place in them. The absolute monarchy does not have the same significance as object in them, and that is why their worlds are not the same. We could say that, like Pascal’s sea, which changes because of a rock,2 the political, theoretical, and philosophical worlds of Machiavelli and the natural law philosophers change because of a mode, because of the modality of existence of the object that absolute monarchy, absolute political power, comprises in their thought.

To mark this difference, we can say the following: Machiavelli’s world is one in which the absolute monarchy, the national state, exists not as a real, existent, instituted object, but as a political objective to be realized. For Machiavelli, in other words, national unity is not an accomplished fact, but a fact to be accomplished. We have already shown that Machiavelli’s thought in its entirety is geared to this task, the task of constituting a new state under a new prince in order to bring about national unity. We have also shown that, for defined political reasons, Machiavelli’s thought had to set itself the altogether unprecedented, radical theoretical task of thinking the conditions of possibility of the existence of that which does not yet exist: that is to say, the task of thinking radical beginning. For, since the initial political basis for national unity was nowhere in existence, it was necessary that it begin; it was necessary to create it. Thus it was necessary to think its absolute beginning; it was necessary to define the conditions of possibility of this absolute beginning. The consequence is that Machiavelli’s object, absolute monarchy, exists in the mode of the political objective, of a political objective. Machiavelli has to think this object under exceptional theoretical conditions that can be summed up as follows. On the one hand, he has to think the fact to be accomplished, he has to think in the fact to be accomplished, in the element of the fact to be accomplished, in the question of the fact to be accomplished. On the other hand – this comes down to the same thing – Machiavelli has to think the beginning as such, and he has to think in the beginning, in the element of the beginning, in the element of the question of the beginning, and so on. There you have the two decisive terms: the fact to be accomplished and the beginning.

Should we say that these two words are two concepts? I shall leave the question in abeyance and say that, even supposing that they are two concepts, these two words are in any case complementary; they define what might be called both the object and the form of Machiavelli’s thought, his specific form of thought. We may add that, in their conjunction, the fact to be accomplished and the beginning are played, in the musical sense of the word, if you like, as if they were the score of a silent philosophy, a philosophy that has not succeeded in expressing itself in philosophical form, the score of a philosophical beginning that has never taken place because no one has ever noted its existence. Thus it is no wonder that Machiavelli should have remained a stranger to all philosophy, to classical philosophy; it is no wonder that dominant and even dominated classical philosophy should have taken Machiavelli to be foreign to philosophy and left him out of account. For that matter, if we consider classical philosophy for a moment, has it ever, for its part, thought in the pair formed by the fact to be accomplished and the beginning? Has that philosophy ever attempted to think the fact to be accomplished and the beginning?

The situation of natural law philosophy is obviously completely different from the situation of Machiavelli’s not-yet-philosophy. Natural law philosophy is dominated by a completely different question. The reason is simple: in the world of these theorists, absolute monarchy or national unity was an accomplished fact – if not a wholly accomplished fact, then, at least, an irreversible fact on its way to being accomplished on perfectly well-known, perfectly well-defined political bases, the history of which shows that they were in the process of expanding sufficiently to accomplish their mission. And, from this simple fact, which still concerns the same referent, but in another mode, there results a first radical difference from Machiavelli.

These natural law theorists think in the accomplished fact; they think the accomplished fact. That, of course, does not prevent them from taking, in their theories, political positions on this accomplished fact of the absolute monarchy: for example, by declaring or demonstrating, like Hobbes, that they are absolutists (in other words, partisans of the monarchy, of the dictatorship of the absolute monarchy in the development of the first forms of bourgeois capitalism); or, like Locke, in a later phase, by declaring that they are liberals; or, like Rousseau, by declaring that they are democrats. At any event, the pros and cons with respect to the accomplished fact, as well as the ‘cons’ directed against certain forms of the ‘pro’ – all these positions observable in the history of natural law are adopted in the element of the accomplished fact. They have nothing to do with Machiavelli’s problematic of the fact to be accomplished.

All this has, consequently, nothing to do with Machiavelli’s question of questions, the question of the beginning. When natural law theory enters, Machiavelli exits; or, rather, we realize that he never made his entrance onto this scene. He was, always and for all time, somewhere else. Thus natural law philosophy thinks the accomplished fact and in the accomplished fact: its object and its form of thought will be determined, as I shall to try to show, in a way quite different from the way Machiavelli’s object is.

Natural philosophy’s object will be political power not as a task to be accomplished, not as a contingent relationship of being to nothingness, nor as event or beginning; rather, its object will be political power as existing, as existent [étant], and this object will be thought in the categories of the existent and the essence of the existent. Natural law philosophy accordingly discusses society, civil law and public law not in terms of chance occurrence and encounter, of event and advent, but in terms of existence and essence. It relates these essences (of natural law, civil law, and public law) to an originary essence, that of the natural law of the originary subject: man in the state of nature.

Whereas Machiavelli thinks in the fact to be accomplished and the beginning, natural law philosophy thinks in the accomplished fact and the origin. The origin, which I am opposing to the beginning here, is obviously altogether different from the beginning. The origin is not the event in which the beginning of a form of eternity supervenes on the ground [sur le fond] of a matter that is already present, always already present, but formless or formed differently. The origin belongs to a completely different mode [mode] of philosophical reference, a completely different world [monde] of philosophical reference. What is the origin? It is the manifestation of titles of legitimacy in the self-evidence of nature: the titles of legitimacy of the truth as well as the titles of legitimacy of every essence and, in particular, the titles of legitimacy of the essence of civil law and the essence of public law.

Why is this so in natural law philosophy? For a simple reason which, obviously, would call for a great deal of explanation, but which we can begin to state as follows: because the idea of the origin that identifies the origin with nature and makes nature self-evident for a subject of law – because this idea of the origin, in the form I have indicated, was then, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the form par excellence of philosophical thought. These terms must be taken in the strong sense: the form par excellence of philosophical thought, that is, the form of foundation, the form of justification, the form of legitimization of philosophical thought, of philosophical thought as founding, justifying, legitimatizing. If, in this period, natural law theorists thought in the origin, it is because the origin was the philosophical form of legitimization of the titles of every essence, and because these theorists had to proceed by way of this common form to justify their own divergent political positions with regard to their common object, absolute monarchy, which had, accordingly, become their common philosophical problem.

So it was that the problem of absolute monarchy became for all of them, pro or con, the philosophical problem of the origin of the state, setting out from the state of origin, the state of nature, and natural law: the problem, the transition from the state of nature to the nature of the state, which was resolved, as you know, by the social contract. I shall go no further for now; I would simply like to say that, in moving from Machiavelli to Rousseau, we change worlds. As we just saw, we change the object of reflection and, simultaneously, we change the form of philosophical thought.

—————

We know who Rousseau is. We know it officially, as it were. Why? Because he has been inscribed in the history of philosophy. And he has been inscribed in the history of philosophy by philosophy itself, which has thus inscribed him in its own history: for example, between Locke and Condillac on the one hand and Kant and Hegel on the other. Thus Rousseau occupies a well-defined place. This place has been accorded him on the basis of the observation of, and reflection on, a certain number of concepts which he put forward and which have been recognized as philosophy by the history of philosophy, by philosophy in its history: the concepts that Kant, for example, singled out in Rousseau.

I would like to try to show that, beyond this official recognition of Rousseau, this inscription of Rousseau in the history of philosophy, there exists an aspect of Rousseau, there exist words of Rousseau’s and arguments of Rousseau’s which, like Machiavelli’s – this is why the comparison does not seem to me to be entirely arbitrary – have practically remained a dead letter. To put it differently, there exist words in Rousseau, and perhaps concepts and arguments as well, which were not registered by philosophy in its history when philosophy drew up the accounts of its history or settled its accounts with its own history. The philosophy that has inscribed Rousseau in its history for one or another merit has drawn up its accounts, and its tallies are accurate – but with the figures it has registered. The drawback, or the boon, is that a few figures, a few words, a few concepts have been left out of account, have been neglected. I would like to try to sketch not an exhaustive inventory of these Rousseauesque words and concepts left out of account by the history of philosophy, but an inventory of just a handful of them.

To this end, I shall be focusing my lectures on the second Discourse, the Discourse on the Origin of Inequality among Men. To pose the problem, I shall set out from the following aporia or contradiction. With Rousseau, we are quite obviously (since I’ve already discussed Machiavelli on the one hand and natural law philosophy on the other) in the same problematic and the same basic concepts as those of the whole natural law school, that is, the same concepts we have found in Hobbes and Locke.3 There are doubtless differences between Rousseau, Hobbes, and Locke, but there were also differences between Locke and Hobbes, between Grotius and Pufendorf, between Burlamaqui and Locke; ultimately, the difference between Rousseau and his predecessors is no greater than the differences between his predecessors themselves. If we were able to speak of a thought common to his predecessors, we have to extend it to Rousseau as well: for the basis is plainly the same.

Let us put that more precisely. The form of thought which we see at work in Rousseau, and which commands everything, is the same form of thought as in his predecessors: it is the thought of the origin, the thought that has recourse to the origin. Rousseau very clearly says in several passages that we must go back to society’s origins to expose its foundations, that there can be no other way: this way is mandatory for everyone. He adds that this origin is man’s nature, man in the state of nature. He repeats, then, what his predecessors have said.

Here, for example, is a passage from the second Discourse: ‘this … study of original man, of his true needs and the fundamental principle of his duties, is also the only effective means for doing away with the host of difficulties that present themselves regarding the origin of moral inequality, the true foundations of the body politic, the reciprocal rights of its members, and countless other similar matters whose importance is equalled only by their obscurity.’4 Elsewhere, Rousseau writes: ‘about [the state of nature] we should … have accurate notions in order to judge our present state properly’.5

The procedure is thus perfectly clear. It is essential to go back to the state of nature, the state of origin, in order to discover man’s nature there: only on this condition can we come to know natural right [droit], natural law [loi], the foundation of societies, civil law, political institutions, and the inequality that reigns among men in our present state. Thus the general form of philosophical discourse remains the same. And, in the general form of recourse to the origin, we see the same major categories of thought come into play in Rousseau as in all his predecessors, namely: the state of nature, the state of war, natural right, natural law, the social contract, sovereignty, civil law. This is the obligatory arsenal of this thought of the origin in the field of law.

These categories are grouped together under three basic moments of reflection that punctuate the manifestation of the essence of law. You know these three moments: the state of nature (the first moment), the social contract (the second moment), and the civil state (the third moment). In Rousseau, as in his predecessors, this originary genesis that sets out from the state of nature does not function like a historical genesis. Rather, in Rousseau, as in his predecessors, it functions like an analysis of essence grounded in the self-evidence of its original credentials, nature.

You may recall that Hobbes proposed to consider society as ‘dissolved’, as he puts it, in order to discern its original elements. Rousseau, for his part, calls on a different image: that of foundations buried in dust and sand. ‘Human institutions’, he writes, ‘appear at first glance founded on shifting sands. It is only on closer examination, only after clearing away the dust and sand surrounding the edifice, that we perceive the unshakeable base on which it has been built and learn to respect its foundations.’6 If we compare this image of the foundations, ‘after clearing away the dust and sand’, with several other passages in the second Discourse, in particular the famous lines in which Rousseau says that the state of nature may never have existed, it seems quite certain that, in Rousseau, the originary genesis is not a real genesis, a historical genesis, but is simply, as in his predecessors, an analysis of essence that takes the form of a genesis which is not historical, but theoretical. Why? In order to justify the determinations of this essence in its origin as the foundation of right.

There we have what strikes every reader of Rousseau. On this common ground, which leagues Rousseau with Hobbes, Locke, and the others, Rousseau is supposed, at best, to have elaborated certain variations of his own which distinguish him from his predecessors, yet are no more, in sum, than variations of one and the same invariant.7 In opposition to this view, which can be defended, but which can also be criticized, I would simply like to suggest one idea, just one, and then I would like to attempt to analyse and demonstrate it.