Читать книгу Emergency Incident Management Systems - Mark Warnick S., Louis N. Molino Sr - Страница 16

1.1 The Revolutionary War

ОглавлениеIt does not take much of a stretch of the imagination to say that IMS methods may have come from early military campaigns that were undertaken in the United States. Some might say that the initial fledglings may have come from other countries. Since this book primarily focuses on the United States, we will discuss only instances in the United States which may, or potentially may not have led to these systems.

Part of the reason for focusing primarily on the United States is also based on expediency. An individual could spend a lifetime trying to make connections between the gazillions (or is it quintillions) of incidents that have occurred worldwide in the last few hundred years. Most of us do not have the time, resources, or even the inclination to take review it so in depth.

We only need to look at the history of the Revolutionary War to understand that some of the principles we see in modern‐day IMS method were used during this war. Initially, the Revolutionary War had no strategy. It was nothing more than a few haphazard militia's fighting against the British when they came into or occupied their geographical location. Initially, there was no centralized commander, no strategy, and no single person, or group of people, in charge. There was no one single person that was charged with coming up with a singular or overarching strategy. In fact, most of the resistance to the British were organized locally and was not part of a larger tactic or main plan. While many of the battles were bloody, they did not follow a strategic battle plan. The objective was quite often to drive the British from the area rather than looking at the bigger picture of defeating the British in all of the colonies.

The Continental Congress began to realize that an organized response was not in place, and some would say they began to wonder if they could win these battles and claim their independence. After much debate and discussion, the Continental Congress appointed George Washington as the General, and commander, of the Continental Army. This occurred on 10 May 1779 (Stockwell, n.d.). By historically reviewing information, we see that Washington began to organize a comprehensive plan, and when implemented, Washington had named it The Grand Strategy (Stockwell, n.d.).

Washington, in his infinite wisdom, unified his battles using the militia from the colony's as the main force, and he integrated the French into specific battles where he felt the militias needed bolstering or reinforcements. He ensured that he provided specific orders for each battle, but he had chosen capable individuals manage the battles. Those capable individuals had the ability and the authority of General Washington to make on‐the‐spot decisions, based on the circumstances at hand.

Some historians have said that Washington's tactics were primarily defensive tactics. They believe that General Washington used a multitude of tactics to exhaust the British, which was sprinkled with hit‐and‐run attacks and a propaganda campaign. The purpose of the propaganda campaign was to undermine the will of the British citizenry and their soldiers (Brooks, 2017). There were some offensive actions taken against the British, but they were often rare.

Those that are learning about IMS methods for the first time should realize the similarities of the propaganda campaign of General Washington, and the IMS methods of today. In Washington's propaganda campaign, the successes of those fighting for independence (such as the militias and specific individuals) were touted. Additionally, the failures of the British were exploited, and their successes were rarely mentioned. This strategic release of information led to more support for the overall effort of war and independence.

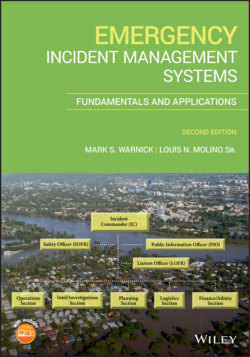

When IMS methods are used in modern‐day times, there is nearly always a component that covers public information. In most instances, this is a Public Information Officer (PIO) or the utilization of a Joint Information Center (JIC). Modern‐day Public Information Officers (PIO's) fashion the release of information, but they do not use propaganda. Similar to the propaganda that was released by the Continental Army, the PIO and/or JIC strategically release information to garner support for their cause: the support for the management of an incident. While this is not propaganda per say, it is a similar method to garner support and provide information about an incident. It is easy to see that at least in some respects, it mimics the work that General Washington employed to help win the war.

In looking at the potential of a historical military connection to modern‐day IMS methods, French General Jean‐Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau arrived to assist with the struggle to gain independence in July 1780. He and General Washington would work together to fight the British, but prior to Rochambeau's departure from France, King Louis XVI advised him that he should be subordinate to General Washington. Essentially, General Rochambeau played a supportive role for the Continental Army, and he would work under the command of the Incident Commander (IC), General George Washington. While Washington was in charge, he also held planning meetings with Rochambeau. Historically, we see that these meetings were held between General Rochambeau and General Washington prior to an offensive to ensure that everyone was on the same page and to ensure everyone knew their role in these attacks (Covart, 2014).

If we compare the actions of Washington in the Revolutionary War to that of the modern‐day IMS Method, we can see that there are multiple similarities. We can start with the appearance that a centralized command was initiated. That centralized command gave strategic instructions to subordinates on what should be done, but it also gave authority to a specific person (or persons) to command how that goal was met. This is a customary practice in all forms of IMS methods in use today. There is typically a centralized command on every incident, even if that centralized command is a group of individuals (Unified Command which will be explained in Chapter 7). This centralized command will always provide guidance and direction, but in most instances, the commander will provide the strategy and then give authority to a person who will make the field decisions.

From a historical perspective, we can see that General George Washington was assisted by an outside organization, and that organization was subordinate to the centralized command. We also see that General Washington held planning meetings, which utilized multiple individuals who helped in guiding the direction of the response, creating comprehensive strategies for the incident, or in this case, the war. A similar method is also undertaken in the IMS methods of today. In the planning phase, the centralized command utilizes the expertise of many (who are experts in specific areas) to come up with an overall comprehensive plan that is strategic. This type of planning helps to provide fewer surprises and creates contingency plans for if an incident does not go as expected.

Since the Revolutionary War, the United States Military has used similar methods to organize their strategies. It should be noted that this theory about the Revolutionary War contributing to modern‐day IMS is not widely acknowledged. Nonetheless, it has striking similarities, which might support that the Revolutionary War at least played some type of role in the IMS methods that we use today.