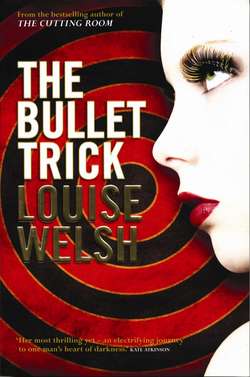

Читать книгу The Bullet Trick - Louise Welsh - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Berlin

ОглавлениеTHE MAN WHO ran the cabaret was a German called Ray. He was the opposite of Bill, a soft-bellied doughy-faced rectangle of a man. He had blond hair shot through with grey flecks that looked too artful to be natural. And a tense smile hedged beneath a shaggy moustache I was willing to accept as German fashion, but at home would have made me think he was a gay man on a retro kick.

I put out my hand and he took it hesitantly, giving it the briefest of shakes.

‘How was your journey?’

‘Fine.’

Ray nodded. ‘Good.’ He looked me up and down. ‘I’d hoped you’d be able to perform in our opening number with the rest of the ensemble but …’ He shook his head sadly and smiled like a man who had faced enough disappointments to know that he would face many more. ‘Never mind.’

‘Try me.’

He shook his head.

‘We will manage. So, I guess the first thing is to show you around the theatre.’ I followed him from the tiny ticket office and out into the auditorium. ‘This is our hall.’

Ray paused, waiting for my reaction at my first glimpse of his kingdom.

I’m used to the abandoned atmosphere empty theatres take on during the day. Deserted by audiences they lose their sheen. When the house lights go up the grandest chandeliers can look cobwebbed, the finest gold-framed mirrors age-spotted and marred. The red velvet seats where theatregoers dream themselves onto the stage night after night reveal frayed gold trim and balding nap. But I knew that, like the leading man who arrives grey-stubbled and sour-breathed, or the femme fatale who dares to bare her pockmarked face to afternoon rehearsals, come curtain-up great theatres are ready to wow them all the way to the gods.

Still, I had my doubts about the Schall und Rauch. When I’d called him back to accept the gig Rich had built the revue into something between the Royal Festival Hall and the Hot Club of France. I’d known he was exaggerating, but I hadn’t realised how much.

The auditorium smelt of mildew, tobacco and wet coats. Its dirty pine boards were still littered with the debris of last night’s performance. Small tables, spattered with red candle wax and equipped with bentwood chairs, were regimented across the hall in diagonal rows. The formation was an optimistic attempt to create an unimpeded view of the stage, but it made me think of a desperate army making its final stand.

The safety curtain was up, the unoccupied stage littered with random props, a large ball, a tangle of hula-hoops, and, somewhere near the back, a trampoline. The stage was deep, its rake steep, but it was the ceiling that revealed this had once been a truly impressive building. High above our heads plaster cherubs toyed with lutes and angelic trumpets amongst bowers of awakening plaster blooms. Remnants of white paint still illuminated some of the chubby orchestra, but most of them had sunk into the same mouldering grey that covered the rest of the ceiling. In its centre, half hidden by the lighting rig, was a chipped but still elaborate ceiling rose marred by a half plastered hole where I guessed a massive chandelier had once hung. Cracks fractured out from the damaged rose and into the outskirts of the ceiling. Not all of them were linked, but they gave the impression of being connected, like irrepressible tributaries sinking underground when the earth turns to stone, but always resurfacing.

‘Have a seat,’ Ray pulled out a chair and lowered himself into it, ‘see what it’s like to be one of the audience.’

I drew up a chair, turning at the hollow sound of footsteps on the wooden floor. A slim, dark-haired girl strode in and started to wipe the tables, putting debris of crumpled tissues, abandoned leaflets and empty fag packets into a tin bucket as she worked. I smiled but she looked past me to Ray, shooting him a sour look. Ray attempted a smile.

‘So, what do you think? Maybe not as big as you’re used to, but it has a certain charm?’

The girl saved me from answering, calling something in German across the hall. Ray answered quick in a tone that might have been friendly or harsh. She turned away from him, reciting a few words in a singsong voice, then tucked the cloth into the back of her jeans and walked towards the exit. Ray shook his head, ‘Women, the same across the world, impossible and irreplaceable.’ He smoothed the grey moustache slowly, like he was calming himself. ‘I know your agent negotiated a few days of freedom before you start…’ I could feel it coming, the not-quite-deal-breaker the management hits you with to soften you up for the rest of the betrayals. ‘But in this business we have to be flexible.’

He paused and I gave a noncommittal smile. On the stage behind him a well-built man in cut-off sweats started going through a warm-up, easing into some stretches, then lifting his leg high in a balletic pose. I nodded towards him and said, ‘I’m not sure I could manage that level of flexibility.’

Ray frowned then turned to look at the man.

‘Acrobats aren’t worth the trouble. You invest in them, break your back helping them, then they go and do the same, only they break their backs for real. Kolja is talented, but acrobats have short lives; he’ll be walking with a stick or teaching sports in a kindergarten before he’s thirty.’

‘Seems harsh.’

Ray shrugged his shoulders. I could imagine him sending a ten-year-old to drown a sack of kittens with the same shrug.

‘It’s a fact. These kids go to circus school. They know the odds, but still think they’ll live forever. That is natural too.’

On the stage Kolja stopped his stretch to watch us. I thought I saw amusement in his face, but he turned away too quickly for me to be sure. Perhaps Ray saw it too, because he leaned back and shouted something in German towards the athlete. The young man made no reply, but his mouth set into a stiff smile as he punted himself down from the stage.

‘There’s no time for you to go to your lodgings now. He’ll put your luggage in the dressing room.’

I got to my feet.

‘I’ll do it myself.’

Kolja walked past without glancing towards us, leaving me standing awkwardly by the table. I sat back down and lit a cigarette. Ray shrugged. He sounded tired.

‘He’s proud of his muscles, let him use them. Come on, let’s finish our business, then perhaps you’ll do some prepa rations.’

‘Perhaps.’

Ray smiled and led me through to his office.

‘So this is my sanctuary. Anytime you need to find me, you start looking here.’

Ray’s sanctuary was cramped. A workbench ran the length of the far wall, hidden beneath stacks of paper and some surprisingly new computer equipment. A small window above the bench looked into the ticket-booth where the girl who had been clearing the tables was now busying herself behind the desk. Beyond her I could see the empty foyer and an open door leading out into the courtyard. The wall behind me was covered in a mosaic of photographs, some expensively framed, others carelessly sellotaped to the wall. I looked at a smartly mounted photograph of a man in full evening rig placing his head inside a polar bear’s mouth. The man had removed his top hat for the act, and now flourished it in his right hand. His own grin was just visible through the jagged teeth of the bear.

Ray saw me looking and said, ‘My grandfather.’

‘It’s an amazing picture.’

‘More amazing than you can know. Outside the ring my grandfather was as soft as butter. People said he let his children run wild, but when it came to animals he was in charge. He ruled lions, tigers, polar bears even, for thirty years, with no injury to himself or to them.’

‘A brave man.’

‘Yes, he knew the risks.’ Ray turned his attention to his desk, sifting through a pile of papers looking for something. ‘The moment after that photograph was taken the bear attacked him, perhaps the flash provoked it. My grandmother was his assistant. She was standing by the cage, as she did every night, with a loaded pistol. She shot the bear, but it takes more than a single bullet to kill a creature like that.’ He glanced back at the photograph. ‘It’s something we should all remember. Even if you’re not placing your head in a bear’s mouth, show business is a risky occupation.’ He smiled. ‘It’s a sad photograph. Let me show you one that will make you smile, then you can meet our stage manager and go through your requirements.’ We rose and Ray walked me into the theatre’s small foyer. ‘Look.’

Pinned behind glass was a large poster featuring a publicity shot Rich had insisted on three years ago. It was a while since I’d looked closely at it and blown up poster size it was clear that the intervening years had been crueller than I remembered. The suit I was wearing no longer fitted, and either the photographer had employed an airbrush, or I’d grown a deal redder and a trifle more craggy since we’d met. The man in the picture looked younger, leaner, sharper than I ever recalled being. It was even possible that he had a little more hair than me. I stroked my hand across my head wondering if I was about to add baldness to my list of worries. Ray’s expression was hidden behind the grey moustache, but his voice sounded anxious.

‘What do you think?’

I looked at the red lettering scattering superlatives across the poster. My German might be non-existent but I could guess the meaning of Fantastisch! I turned to the posters hanging beside my boastful image and it suddenly became clear why Ray had decided I was unsuitable to join the ensemble. Schall und Rauch’s cast shone from the picture fresh and smiling, the outlines of their bodies impressive beneath the tight fabric of their costumes. The recognition that Ray was right stung, but another more pressing worry had suddenly presented itself. Painted in shiny blue letters below the image was the legend, Cabaret Erotisch!

*

The stage manager turned out to be the girl I had first seen wiping the tables. She slid wearily from the ticket booth, brushing back tendrils of not very clean hair that had escaped from the loose roll twisted at the back of her head. She looked as if she hadn’t slept in weeks, but the look suited her. Suddenly, despite the rundown theatre and the reminder that I lacked the basic equipment to qualify for an erotic entertainment, Berlin didn’t seem such a bleak prospect. Ray introduced her as Ulla; I held out my hand and she shook it gently. Her palms were cold and dry and slightly calloused. I tried to keep the wolf out of my face and asked, ‘Do you do everything round here?’

Ulla frowned.

‘I do my job.’

Her English was slightly more accented than Ray’s. I liked it better. She was easier on the eye too, even when she was frowning. I slipped the duster that still dangled from her jeans pocket into my own.

Ulla led me through a door marked Privat and towards the changing rooms. Her silence should have been a relief after the journey, but I wanted her to talk to me. I reached into my pocket and drew out the old duster now tied in the centre of a ream of rainbow-coloured silks, presenting them to her with a flourish and a half bow.

‘There was no time to buy flowers.’

Ulla accepted the string of scarves without smiling.

‘The clowns present me with flowers all the time.’

‘And now you think every bouquet is going to squirt water in your eye?’ She ignored me, gently detaching her cloth as she led the way through the backstage labyrinth. ‘I hope I’m not disrupting you too much.’

Ulla handed back my crumpled silks without looking at me. I followed her gaze and saw the object of her attention. The buff athlete detailed to deliver my case was striding our way, a large cardboard box tucked casually under his arm. He stopped when he reached us and Ulla raised her face to his in a swift but tender kiss. I stood awkwardly while he whispered something into her hair that made her laugh then shake her head, glancing quickly towards me. Kolja turned the corners of his mouth down, gave her waist a quick squeeze with his free hand, and then continued along the corridor. Ulla’s eyes followed him briefly and then turned back to me.

‘Kolja has moved in with the twins, so you can have his dressing-room.’

There seemed no point in protesting that I was used to sharing. After all, I seemed destined to disrupt Kolja. The room Ulla had assigned me was like a slim prison cell bereft of even a barred window. I sat in the only chair and looked at the photos of Kolja stuck to the mirror.

He was a good-looking lad. Here he was on stage balancing an upside-down fellow athlete on one hand. Here he was again, stripped to his bathing shorts posing with both hands resting on his waist, his pumped-up arms a perfect complement to his inflated trunk. Did Kolja need these mementoes as reassurance of his athletic prowess? Or did he just like looking at himself? I wondered why he hadn’t taken the photographs to the twins’ cell with him. There were a lot of them, but not too many for Kolja’s muscular arms. Perhaps he’d been in too much of a rush or maybe he didn’t think I’d be around long enough to warrant the move. Whatever the reason I hoped I hadn’t upset Kolja. He looked like he could destroy me with a flick of his wrist.

Outside I could hear exchanges of greetings as staff and performers started to arrive for that evening’s show. I imagined I could smell the winter damp settled on their coats. I pushed the noise away, tried to ignore the resentful stares of all the different Koljas and concentrated on preparing my act.

*

Ray’s moustache trembled a little when he saw me leaving the theatre half an hour before show time, but he knew better than to interrupt a performer before their act. Folk have strange rituals and who was to say mine wasn’t walking out before I walked on?

There was a stall in the courtyard selling soup that was all noodles and dumplings. I bought myself a bowl, added a beer to go with it and sat on a wooden bench in sight of the theatre entrance, watching the audience arrive.

Unless you’re a children’s entertainer, your audience doesn’t believe that what you’re doing is truly magic. They want showmanship. Anyone can feel the satisfaction of teaching their hands to twist the rope until it unravels the way they intend. It isn’t so hard to jump the right card from the deck, or snap a shiny silver coin into your fingertips. The skill lies in making these moves into a performance.

I was always in the smart-suited-cheeky-chappy conjuring brigade, bounding on stage and spinning a line as I spun through my act. I’d long ago consigned mime to a box marked ‘puppets and face painting’. I lacked the nimbleness for a dumb show. And all those exaggerations of the face and form, the Marcel Marceau smiles and grimaces, made me cringe. Sitting outside the theatre in Berlin I began to think how important words were to my act and began to hope that it was true all foreigners understood English these days.

The arriving audience looked young, bundled against the cold in dark coats livened by bright hats and scarves. I watched them drift in and wished I was one of their number, out for the evening with a pretty girl, looking forward to a show. I got up and returned my empty dish and half-drunk beer to the stall. It was time to get focused.

Inside I bought another beer, deposited myself on a seat near the back and watched an old woman in a black dress going between the tables trying to sell the contents of her tray of clockwork toys. She wasn’t having much luck. I signalled her over and blew twelve euros on a small tin duck. I turned his key and let him clack between the ashtray and my beer.

Then the lights dimmed, the audience grew quiet and high on a platform, way above the stage, a woman with the black hair and red lips of Morticia Adams grinned and stroked the ivories of her baby grand into something soothing that spoke of the sea. She reached out her right hand, never letting the music fail, and caressed a huge hollow drum as it descended past her to hang mysteriously over the stage.

The ensemble from the poster ran from the wings, the females in thigh-skimming dresses, the men in close-fitting shorts. Kolja jogged on last, his face shuttered and his muscles specially inflated for the occasion. The troupe waved to the audience, acknowledging their applause then stood still, like a starship crew ready to be teleported, as the glowing drum descended all the way down to the stage, trapping them within its bounds, silhouetting their forms against its pale walls. One by one each dark outline peeled off its clothes to reveal the black shape of their naked body, then they started to rotate slowly, forming a living magic lantern. Each disrobing received a polite round of applause that was rewarded with a pose as the artistes took turns to fold themselves into new shapes, slipping from athletic to romantic, from Charles Atlas to Rodin’s Kiss. There were no unfortunate bulges, no regrettable slips of decorum, and I guessed that the nudity was an illusion, each person contained in some tight-fitting body stocking. Kolja was the easiest to spot. His was the widest chest; the thickest thighs. It was he who held two seemingly naked girls on his shoulders, balancing their weight like a set of human scales. He too who got the loudest applause as he flexed his physique through a catalogue of muscleman positions. Overall it was a good effect, an innocent erotic, about as naughty as an Edwardian postcard.

The first of the performers to appear solo was a lithe lycra-clad girl with a blonde ponytail, who seemed to be in love with her hula-hoop. The audience sat still in anticipation as she twirled the hoop around her body, letting it rotate her waist, chest, neck then suddenly drop to her ankles in an act of obsequiousness that seemed sure to kill its gyrations, but was merely a prelude to a snaking dance up her body and onto her right arm. Her hand snatched a second hoop, rival to the first, which proceeded to do its own dance around her curves. It seemed this girl couldn’t get enough of the hoops. She lifted them one by one from a pile as high as herself until she had screwed her little body into a spiral of weaving plastic. The small audience went wild and my tiny tin duck clacked like there was no tomorrow.

I was hoping for Kolja, but the hula girl was followed by a trio of juggling clowns. They cavorted onto the stage dressed in bright baggy shorts and outsized shirts. The tin duck drew me a sad stare, I took a sip of my drink and nodded back at him. The crowd were clapping them on but the jolly jesters looked too wholesome to amuse me. I’ve always preferred Kinky the Kid-loving Clown, a hard-drinking funster who has his full makeup tattooed on.

Somewhere a violin started to play a waltz and onstage the trio began tossing their batons gracefully in time to the music. I could see where it was going. The tempo increased and so did the speed of their pitches until the music sounded like a fiddler devil’s crossroads challenge and the clowns were flinging their batons like missiles, ducking to put their partner in the frame, turning the cat’s cradle of their throws into a crisscrossing sequence it was impossible to anticipate. The speed increased, a baton or two was lost, after all a trick must never look too easy, then, just when the audience were getting used to their expertise, the entire volley was turned on the smallest of the three, who caught the batons with his hands, arms, legs and feet, looking askance at the final club before catching it deftly in his mouth. The audience cheered. The troupe acknowledged the applause with a series of synchronised back-flips, then the runt ran offstage and returned brandishing three buzz-saws and a manic smile. I got up and made my way back to the wings. I left the duck on the table. It would be nice to think that someone in the audience was rooting for me.

*

The clowns finished their not-so-funny business then flip-flopped offstage accompanied by music that was an improbable mixture of oompa and punk. The crowd clapped and stamped to the rhythm and the irrepressible funsters cartwheeled back on for an encore, throwing buzz-saws at each other with calamitous abandon before finally running unscathed into the wings.

The little one buzzed his saw at me as he sped past. I muttered, ‘Buzz off’. And he flashed me a wicked grin saying something in German that might have been Good luck or Fuck you.

Two stagehands dressed like ninjas jogged on to clear the clowns’ debris and deposit my equipment. The mysterioso music I’d given Ulla reached its fifth bar. I took a deep breath and strode out from stage right as the stagehands exited stage left. The clown’s applause still trembled in the air. I measured it, gauged the warmth of the crowd, pretty hot, and realised that for once I wasn’t the warm-up.

I lifted a flimsy transparent perspex table above my head, twirled it like a baton then waved my hand Mephistolike below it and snapped a set of oversized playing cards into view. Beyond the edge of the stage there was nothing but black punctuated by the candle flames glowing out of the darkness. God looked out into the firmament and saw nothing. Then he snapped his fingers and created the world. I gave the slightest of bows, and got on with it.

*

Have you ever seen a film of an ocean liner ready to embark on a long voyage? People were so loath to leave their loved ones that they stretched streamers from the decks to the quayside. The nearly-departed held one end, the soon-to-bestrangers on the shore, the other. As the ship moved off the streamers would grow tense, taut, then break.

That was the image I had of my audience’s attention, slender strips of colour connecting them to me. I wanted to keep them at the moment the ribbon was at its tautest, and never let it snap until my final bow.

The music died and I slid into my set, I was halfway through the first trick when I heard the whisper of conversation. The fragile strands connecting me to the audience snapped and it was as if I was a lonely soul on the top deck holding a bunch of limp streamers without even a breeze to give them a flutter.

There was a clink of glass on glass as drinks were refreshed. A jarring note of laughter where there should have been the silence of suspense. I did the only thing I could do, kept the smile on my face and stumbled on until the moment came for the house lights to be raised. Now I could see the faces of my audience, too many of them in profile. I stepped forward, feeling like a man on the scaffold, and asked for a volunteer.

Later, Sylvie would show me this was the wrong way to go about things. But that evening even the old lady who sold the tin toys stopped her rounds and waited for my humiliation. I paused three beats beyond comfort, unable to spot a dupe amongst the crowd, putting all my will into not begging. The stage lights seemed to flare again, the audience bled out of focus and even the candles seemed to lose their glow. A bead of perspiration slid down my spine. Then a young woman got to her feet and I knew everything was going to work out fine. And so it did, for a while.

The girl bounded onto the stage with so much confidence I suddenly thought the audience might assume her to be my accomplice. I shouldn’t have worried. Even on that first night, though I was the one with the tricks and the tailcoat, everyone wanted to see what Sylvie would do.

*

My volunteer was a slim girl in high-stacked boots and an old-fashioned shirtdress that showed off her figure. Her hair was sleek, cut close to her head, and her lips were painted a vampire red that glistened under the stage lights. She turned to face the audience. Her stare was confident, her mouth amused and I realised I should never have chosen her for my dupe. I swallowed, arranged my features in the semblance of a smile then went into my patter.

‘So, gorgeous, what’s your name?’

‘Sylvie.’

She had an American accent, all Coca-Cola, Coors and Marlboros, a bland corporate voice that could have come from almost anywhere.

‘And what brings you to Berlin?’

Sylvie shrugged and looked out into the darkness beyond the stage.

‘Life?’

The crowd laughed, and I smiled, though I didn’t see the joke.

‘So, would you like to help me with a trick?’

‘I guess so.’

Again her voice was deadpan and again a ripple of laughter worked its way through the audience. I might not be getting the jokes, but I was grateful. The clatter of glasses and conversation had ceased and all eyes were on us, the audience rooting for Sylvie, waiting for her to upstage me.

I turned her towards me, looked into her grey-green eyes and grinned.

‘OK then, let’s get on with the show.’

The shell game is an ancient trick also known as Chase the Lady, also known as Thimblerig. The man who first taught me prefaced his lesson with a warning.

‘This is a trick as old as Egypt – older, I don’t doubt. It has saved many a man from starvation and landed many another in debt or jail. The wise man is always on the showing side, never on the guessing.’

My old teacher was right, but it isn’t big news that it’s better to be the sharper than the sharper’s dupe, so my variation had an extra distraction to twist the ruse.

I fanned three brown envelopes in my left hand, and raised a picture of the crown jewels in my right, holding it high in the air so that the audience could see it. I’d thought that the royalist kick might go down well with the Germans, after all, they were related. I slid the photograph into one of the envelopes, making sure that Sylvie and the audience could see which one it was.

‘Sylvie, how would you like to win the British crown jewels?’

Her voice was dry.

‘The real thing or this photograph?’

I feigned an outraged look.

‘This rather fine photograph.’ Sylvie laughed and the audience joined her. I kept the note of injury in my voice. ‘What? You don’t find it exciting?’

She shook her head matching my mock offence – ‘No’ – and turned to leave the stage.

‘Hey, hold on.’ I touched her shoulder and Sylvie twisted back towards me on cue, as if we’d been rehearsing for weeks. ‘What about if I were to offer you…’ I leaned forward and snapped three 100 euro notes from somewhere behind her ear. It was the kind of cheap move a half-cut uncle could manage after a good Christmas dinner, but for the first time that night I got a round of applause.

It’s hard to convey the look that Sylvie gave me. A smile that acknowledged we were in this together and a glint of sympathy cut through with something else, an urge to please the audience that might amount to recklessness.

‘Yes,’ she said in her cool, who-gives-a-fuck stage voice. ‘Yes, that might make a difference.’

I slid the money into the envelope alongside the maligned picture and sealed it tight.

‘Now, Sylvie, examine these envelopes for me please.’ I passed all three to her. ‘Are they identical?’

She took her time, turning each one over in her hand, scrutinising their seals, drawing her fingers across their edges. At last she turned and nodded.

‘Yes, they’re the same.’

‘Now…’ I feinted a soft black velvet hood into my hands. ‘How do you feel about a little S&M?’

Sylvie made a shocked face and someone in the audience whooped.

Sylvie’s fingers were strong as she secured the hood over my head. She tied the cord in a bow at the nape of my neck, then smoothed her fingertips over my face, pressing them against my eyelids for a second. I felt the prickle of total darkness and breathed in the faint peppery mustiness that the velvet bag always held, pulling the fabric towards me as I inhaled, letting my masked features appear beneath the velvet.

‘I want you to take these envelopes and shuffle them in any way you wish.’ The audience laughed. I wondered what she was doing and asked, ‘All done?’

‘Yes.’

‘Now, I’m going to ask you which envelope the money is in. You can lie, you can tell me the truth, or, if you choose to be a very unkind girl, you can keep silent. The choice is yours.’ The audience were quiet, willing my destruction. ‘OK, Sylvie, I want you to present me with each of the envelopes in turn. But because I can’t see anything you’re going to have to provide me with a commentary, so name them please as you hold them up. Let’s call them… ’ I hesitated as if thinking hard. ‘Number one, number two and number three. OK, in your own time.’

Sylvie waited a beat, then in a loud, clear voice said, ‘Number one.’

I lifted my head, breathing in again, hoping my covered features looked blunt and dignified, like an Easter Island statue.

‘Is it in this one?’

I waited. Sylvie didn’t respond.

‘Ah, I thought you might be one of those girls who like to torture men.’

No one in the audience would have noticed, but Sylvie gave a short intake of breath. She recovered quickly and said in her calm, even voice.

‘Number two.’

‘Is it in this one?’

This time she answered me.

‘No.’

‘Aha, you’re not an easy girl to work out, Sylvie. I’ve got a suspicion that you might be rather good at lying.’

The stage was so quiet that I might have been standing there alone. I felt the warmth of my own breath inside the bag, then Sylvie said, ‘Number three.’

I waited. This time it was my silence that ruled the stage.

‘OK, if I’m wrong you go off with a week’s wages. Is it in this one?’

There was an instant’s hesitation and then Sylvie answered me.

‘No.’

It was the hesitation that told me. I took my chance, snatching the hood off then grabbing the final envelope, ripping it in two and drawing out the money and the photo. The audience applauded and I raised my voice above their clapping, ‘Thank you Sylvie, you’ve been a wonderful assistant. People from Scotland have a reputation for being mean, but it’s a cruel slur and to prove it I’m going to make sure that you don’t go off empty-handed.’

I presented her with the photograph of the crown jewels. Sylvie held it close to her head and bowed prettily to the audience. We exchanged a quick kiss, and then I watched her slim figure descend into the darkness and the applauding audience beyond.

I thought that would be the last I saw of her.