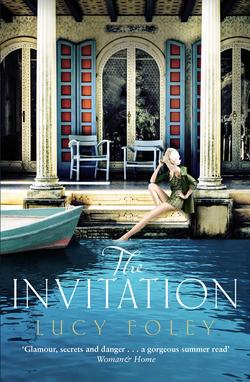

Читать книгу The Invitation: Escape with this epic, page-turning summer holiday read - Lucy Foley, Lucy Foley - Страница 12

4 Liguria, April 1953

ОглавлениеHis first impressions of Liguria are snatched through a smeared train window. These are visions at once exotic and banal: washing strewn from the windows of red-tiled, green-shuttered houses, road intersections revealing a chaos of vehicles. Palm trees, tawdry-looking railway hotels. The occasional teal promise of the sea. The sea. At the first glimpse of it he finds himself gripping the seat rest, hard. Sometimes it has this effect on him.

This whole mission still has about it an air of unreality. If he hadn’t had that slightly stilted meeting with the editor at Tempo – who seemed as bemused as he did as to why he had been chosen – he might have reason to believe it was all the Contessa’s little joke.

‘Keep it light,’ the man had said. ‘What do the stars eat and drink, what do they wear? What is Giulietta Castiglione reading, ah, what does Earl Morgan do to relax? Stories of cocktails in Portofino, of sun on private beaches. Of … of a sea the colour of the sapphires our leading lady wears to supper.’ Hal had tried not to smile. ‘Nothing too worthy. Our readers want escapism. Niente di troppo difficile. Capisci?’

‘Si,’ Hal had said. ‘I understand.’

La Spezia is no great beauty, though there is a muscular impressiveness to the place, the harbour flanked with merchant vessels and passenger ferries. Not so long ago there would have been warships marshalled here. To Hal they are almost conspicuous in their absence. The enemy’s own destroyers and submarines, sliding beneath the surface black and deadly.

He catches the passenger ferry, and realizes that it is the first time he has been afloat in years. Again, he reminds himself, it is all different. The tilt and shift of the boat much more pronounced; so close to the water that he can feel the salt spray on his cheek. He concentrates on the sights. Here, finally, is the fabled beauty: the land rising smokily beyond the coast, the clouds banked white behind. A castle, rose-gold in the afternoon sun.

He looks at his fellow travellers. Poverty still pinches some faces tight, clothes are a decade or more out of date. Marshall Aid, it seems, has not lessened the struggle by much for them. In the relative prosperity of the capital it is easy to forget – to feel, sometimes, like a poor relation.

At Lerici, a little way down the coast, all the passengers disembark. Hal hasn’t yet worked out this part of the journey, but according to the map the place should be only a few miles by water. Hal goes to the skipper, who lounges against the stern with a cigarette and scowls at him through the smoke.

‘Il Palazzo Mezzaluna?’

The man takes a lazy drag, squinting as though he hasn’t understood. Hal repeats himself. As comprehension dawns, his question is met with a short, derisive bark of a laugh, a shake of the head.

‘No,’ the man says. ‘It isn’t on my route. It is a private residence.’

‘Yes,’ Hal says. ‘But for a little extra?’

‘No, signor. I am finished for the day.’ But as Hal turns to leave him he shouts something, gesturing to several small crafts heaped with fishing gear. A group of sunburned men sit near them, sharing an impromptu picnic of bread and shellfish, shucking them with their knives and sucking the morsels from the shells.

Hal approaches them and asks his question. One of the men shrugs and stands, brushing breadcrumbs from himself. He leads the way over to his boat and moves a few items around – nets, a can of oil, a box of bait and a rod – to make room for Hal and his bag. Hal clambers in, aware of the ambivalent gaze of the men who remain, eating their oysters. What do they make of him, this Englishman in his tired suit, climbing in beside the fishing tackle?

The man starts his engine and they putter out of the harbour, pitching dangerously as they cross the wake of a larger boat. Then back out into the navy blue of the open sea, rounding the nub of the headland. The little boat speeds across the water, sending up a fine salt spray. After only fifteen minutes or so the man points to the shore.

‘È là!’

In the distance: a semicircular opening in the dark mass of trees, separated from the water by a silvery thread of sand. And nestling among the trees, dead centre, an enormous building. A grand hotel, one might presume, seeing it from afar. As they draw closer Hal is better able to make it out. A palace, in the Belle Époque style. The façade is a coral pink that anywhere else in the world would look ridiculous … and yet here, drenched in the evening sun, is something like magnificent. A white jetty stretches out like a piece of bleached driftwood into the blue depths. A figure waits, watching their approach.

Hal steps onto the jetty, heaving his bag after him. The waiting figure is a liveried member of staff who strides toward Hal, hand outstretched for his luggage. Against the spotless white of his uniform the leather case looks small and battered.

‘Good evening, sir.’

Hal goes back to the fisherman, pays him, quickly. The man seems a little bemused, as though he had never expected his shabby passenger to be welcome in such a place. With a shake of his head, as though to clear it, he fires his engine and is gone.

It is evening now, Hal realizes, the light like blue glass. Before them rises a shallow stone staircase flanked by a line of pine trees. Each is topped by a fluid dark abstract of foliage, like a child’s drawing of a cloud. Their resiny scent fills the warm air. The man leads the way, moving so briskly that Hal has to jog a little to keep up. They move past a series of gardens, each, Hal sees, is different from the last. ‘The Japanese garden,’ the man says, as they pass the first: and in the manmade pools Hal glimpses an iridescent carp, sliding fatly among trailing pondweed. There are ornamental bridges, gravel raked into intricate patterns about carefully shaped hillocks of moss. Then the Moroccan garden, filled with bright blooms that spill from urns painted a luminous blue. The Italian garden: a stately formal arrangement of dark shrubs and classical statues. As Hal and his guide pass, a flock of white doves take wing. It is itself like a film set, Hal thinks, hardly real.

Inside, the house is a cool space, reminiscent of an art gallery. A couple of line drawings that might be Picasso – his eye isn’t good enough at this distance to be certain. A cuboid nude that could be Henry Moore.

The room that he is shown to is white, high-ceilinged.

‘You can change here for the evening,’ the man tells him. ‘Drinks are at seven thirty.’ Hal looks down at his travelling suit. Change into what, exactly? The suit is crumpled, but it is by far the smartest thing he owns. He wore it because it is the smartest thing he owns. And so he sits down on the bed, looks about himself. The window has a view out towards the back of the house, where a great stone terrace leads down into further manicured gardens, showing now as a dark emerald green. A space hewn by the twin forces of wealth and will out of the natural gorse. At the far end is a line of tall cypresses. In the weakening light they are black sentinels, funereal in aspect. Suddenly he catches a shimmer of gold, which resolves itself into the hair of a woman. She wears what appears to be a long black dress, camouflaged against the trees behind her so that only her face and arms can be made out. An unnameable excitement runs through him. He goes to turn out the light in the room, so he can make the scene out better, but when he looks back she has disappeared.

At eight o’clock the open window discloses the unmistakable sounds of musical instruments being tuned: the squawk of violins, the throb of a double bass. Hal showers in the gilded bathroom, sloughing off the crust of salt, and glances quickly in the mirror. His clothes are more creased than ever. But his face betrays little of his tiredness. He knows that he is lucky, to look like this. His face is his passport.

When he returns downstairs the gardens have been transformed: lit now by a host of lanterns and filled with guests. Some of the guests are from a similar crowd to the party in Rome; they have that same lustre of wealth, of lives lived on the grand scale. But he sees, too, children dressed as if for the beach, dark-haired girls in simple sundresses, men in casual trousers and unbuttoned shirts. Along one wall of the house a line of elderly men sit and talk with great intensity: all wear battered caps in various sun-faded hues, sandals on hoary feet. The women who Hal presumes are their wives look on censoriously from a few metres away and they, too, wear an unofficial uniform: floral-patterned smocks and woollen cardigans. Hal’s suit no longer seems such a faux pas. But he is aware that he belongs to neither tribe: not that of the dinner jackets, or that of the summer slacks. He is an anomaly.

‘Hal.’

He turns, and finds the Contessa. She is wearing a tangerine linen dress than could almost be a monk’s tabard, with a large hood pulled up over her hair. It is one of the more eccentric outfits Hal has ever seen.

‘I’m so pleased,’ she says. ‘I worried that you would change your mind.’

Hal thinks that she can have no concept of a journalist’s living, if she imagined he might have been able to turn her offer down.

‘I wanted to know something,’ he says, because he has been wondering. ‘How are we travelling to Cannes?’

‘Ah,’ she says, ‘but you will find out tomorrow morning.’

‘All these people are coming too?’ He gestures toward the crowd.

She laughs. ‘Oh, no. No. I have invited them all for the evening.’ She counts off the different groups on her fingers. ‘There are friends, the film crowd, your colleagues from the press’ – she gestures towards a passing photographer – ‘and some of the people from the village near here. They come often – especially the children and their parents – to swim off my jetty, and walk in the grounds. It is why I make such an effort with the gardens. And they appreciate a good party, like all sensible Italians. Wait until the dancing starts. But first I will introduce you to the other guests. Come.’ She beckons with one hand.

The man she leads him to first is etiolated-looking, with blond hair so pale that it is almost white, receding on either side of the head severely. A thin face, with all of the bones visible beneath the skin. He is dressed in a wine-coloured suit – beautifully made, but with the unfortunate effect of making his complexion sallower still.

The Contessa moves into English. It is the first time Hal has heard her use it, and he is surprised by her fluency. ‘Hal Jacobs, meet Aubrey Boyd, who will be taking the pictures to accompany your article. This man is the only true challenger to Beaton’s crown, in my opinion. He is a simply splendid photographer – makes one look like a goddess. He has a way of making all one’s little wrinkles disappear. How do you do it?’ The Contessa is impressively wrinkled even for one of her advanced years. A life well-lived, Hal thinks, much of it in the full glare of the sun.

Aubrey Boyd raises one thin eyebrow. ‘I cannot reveal my magic.’ And then, quickly, ‘Though none was needed in your case.’

‘He did the most wonderful series on American heiresses, didn’t you, Aubrey? Posing like so many Cleopatras and Anne Boleyns. And let me tell you,’ she says to Hal, conspiratorially, ‘none of them will ever look like that again in their lives. I know that your pictures will look fabulous in Tempo.’

‘Yes,’ Aubrey says, a little dubiously. Hal has the impression that he sees the magazine as somewhat beneath him.

Next the Contessa is introducing him to Signor Gaspari, the director, hailed in recent years as a god of Italian cinema. The man cannot be taller than five foot five, the hunch of his shoulders robbing him of a couple of inches. Something about the way he stands suggests a body that has been put through more than its fair share of suffering.

‘My dear friend,’ the Contessa says, as she stoops to embrace him. ‘Meet our young journalist, Hal.’

‘I loved your last film,’ Hal says.

‘Thank you,’ Gaspari says, solemnly, without any visible sign of pleasure.

Hal remembers it vividly. The war-torn city, beautiful in decay. And that protagonist, the solitary man, wandering through it. His aloneness all the more profound for the hubbub of crowds surrounding him. The atmosphere of the film, the exquisite sadness of it. He tells Gaspari this.

‘You have understood my intention well,’ Gaspari says.

‘I wondered,’ Hal says, ‘whether you might have meant it as a lament for Rome – for the country? To what was lost in the war?’

Gaspari smiles – but it is a melancholy, downturned smile. He shakes his head. ‘Nothing so lofty as that, I’m afraid,’ he says. ‘My intentions were … much more human. The loss was one of the heart.’

Hal senses there is a story here – one he is intrigued to hear.

‘Another drink, Giacomo?’ the Contessa asks, as a waiter passes by with a tray.

‘Oh no,’ Gaspari waves a hand. ‘Thank you, but I must be returning to my room now. I wanted to come for a little while, but I am no good at parties. And Nina needs to go to bed.’ He glances down, and Hal follows his gaze to where a tiny dachshund sits, quite still, the black beads of her eyes trained on her master. Then Gaspari nods to them both and moves away, the dog trotting at his heels.

‘A wonderful man,’ the Contessa says. ‘A great friend, and a genius. Some, I know, think he is a little odd. But genius is often partnered with strangeness.’

‘He looks …’ Hal tries to think how to put it. ‘Is he well?’

‘He suffered greatly,’ the Contessa says, ‘during the war.’

Hal waits for her to continue, but she does not. She has turned towards another man, who is approaching them across the grass. He is elegant in fine, pale linen, with leonine hair swept back from his brow. A fingerprint of grey at each temple. He is not particularly tall, but there is something about him suggestive of stature. A trick of the eye, Hal thinks. A confidence trick. He smiles, revealing white teeth. Even Hal can see that he is handsome, in that American way. And somehow ageless – in spite of the grey.

‘Mr Truss.’ The Contessa’s smile is not the same one she gave Signor Gaspari. It is the smile of a diplomat, measured out in a precise quantity.

‘It’s a wonderful party, Contessa. I must congratulate you.’

‘Thank you. Hal, meet Frank Truss – who has been very supportive of the film. Frank Truss, meet Hal Jacobs, the journalist who will be joining us.’

‘Hal,’ Truss puts out a hand. Hal takes it, and feels the coolness of the man’s grasp, and also the strength of it. ‘Who do you work for?’

Without knowing why, Hal feels put on his guard, as though the man has challenged him in some indefinable way. ‘I don’t work for anyone in particular,’ he says. ‘But this piece is for Tempo magazine.’

‘Ah. Well.’ He flashes his white smile. ‘I don’t know it. But, clearly, I will have to make sure to watch what I say.’

‘I’m not that sort of journalist,’ Hal says. It sounds more hostile than he had intended.

‘Well, good. I’m sure you’re the right man for the job. Great to have you on board.’

He speaks, thinks Hal, as though the whole trip were of his own devising. Odd, but there is something about him – his statesmanlike bearing perhaps, his air of entitled ease – that reminds Hal of his father. A man who expects deference. And if he is anything like Hal’s father, it is an unpleasant experience for those that fail to show it.

As Truss moves away, the Contessa turns to him, confidentially.

‘He’s the money behind the film,’ she says.

‘Oh yes?’

‘A powerful man.’ She lowers her tone. ‘He has other business in Italy – industry, I understand. And … It is also possible that he may have certain connections here one would rather not look too closely at. I, certainly, am not going to look too closely at them. Perhaps investing in the arts looks good for him. But he describes himself as a man of culture: so that is how I will view him. And I like his wife, which helps.’

‘His wife?’

‘Yes,’ the Contessa searches the crowd. ‘Though I can’t see her here. Never mind, there will be plenty of time for us all to get acquainted. But – ah – there is our leading lady!’

It is a face known to Hal because of the number of times he has seen it in newsprint and celluloid form. Giulietta Castiglione. Her outfit is surprisingly modest, a sprigged peasant dress, cut high at the neck. Her small feet are bare, more likely a careful choice than real bohemian artlessness. She has black hair, a great thick fall of it – the longest strands of which reach almost to her waist. There is a hum of interest about her. All the men – old and young – are transfixed. From the elderly women emanates a cloud of disapproval.

They say she has already turned down marriage proposals from some of the biggest names in Hollywood and in Cinecittà. And she was engaged, for a period of precisely one week, to her co-star in the film that made her name in America: A Holiday of Sorts.

Hal caught A Holiday in a Roman cinema, dubbed into Italian. It was a blowsy comedy: an American ambassador falls in love with a Neapolitan nun – played, with improbably ripe sensuality, by Giulietta. It should have been the sort of film one might watch to while away a rainy afternoon and then instantly forget. But there had been something about the actress: the combination of knowing and girlish naiveté, the curves of her body at odds with that virginally youthful face. She had been disturbing, unforgettable.

In the flesh, her charisma is more tangible, and more complex. Hal, watching her dip her head coyly in answer to a question from one man, and then throw her head back and laugh in answer to another, quickly begins to realize that she had not been playing a part so much as a dilute version of herself.

‘Well,’ the Contessa says, ‘quite something, is she not?’ And then, ‘Wait until you see her in the film.’

Hal wonders how this sensual presence will translate itself into Gaspari’s work. The two seem as contradictory as fire and water. But perhaps this will be what makes the combination work.

Despite himself, he is beginning to look forward to the trip. Before he had thought only about the money, how it would make everything easier for him. But he sees now that here is the promise of an experience out of the ordinary, one that will help him forget himself. And the chance to be in the presence of a great storyteller; for that is what Signor Gaspari is. To learn from him, perhaps.

At some point the Contessa is drawn into conversation with another guest, and Hal is free to roam on his own. The drinks keep coming and Hal, who for a long while hasn’t been able to afford the luxury of getting drunk, takes advantage of them. By his fifth – every one so necessary at the time – the evening has melted into a syrup of sensation. He wanders through the grounds, meeting guests and forgetting them instantly.

Later, the dancing begins, and Hal finds himself thrust into the fray. The poor girl whose hand he has commandeered trips and squeals, to no avail, as he spins her around and around and around, and the lantern lights become a vortex of flame about them.

In the small hours he wanders down to the gardens. Peacocks strut about freely, disturbed from their sleep by the din of the party. He sits down upon a miniature stone house, blinking in an attempt to clear his head, and observes one of the males. The bird preens himself, his plumage gleaming in the lantern-light, tail feathers rustling importantly. And yet for all the beauty of his feathers, Hal sees that the creature’s feet are scaled and ugly, like a common chicken’s. This suddenly strikes him as philosophically significant.

‘You think you’re special,’ he tells the bird, labouring over the words, ‘but you aren’t. We’re all just chickens, underneath it all, however much effort we put into not revealing it.’

Later, he remembers the woman he saw in the gardens behind the house, at dusk. Though it was several hours ago he has some drunken idea that she will still be there; that he only has to go and look for her. So he makes his way round to the back of the house, and towards the dark line of cypresses, his way illuminated now only by the silver light of the moon. Of course, she is not there. Perhaps she was a figment of his imagination.

As he turns to make his way back to the house – he must go to bed, he knows, or wake up here covered in pine needles – he sees something gleaming dully upon the ground. He stoops, and finds an earring – a stud of some large, cut stone, the colour indiscernible in the gloom. He puts it in his pocket. So she was real, after all.