Читать книгу The Pike: Gabriele d’Annunzio, Poet, Seducer and Preacher of War - Lucy Hughes-Hallett - Страница 9

ОглавлениеTHE PIKE

IN SEPTEMBER 1919, Gabriele d’Annunzio – poet, aviator, nationalist demagogue, war hero – assumed the leadership of 186 mutineers from the Italian army. Driving in a bright red Fiat so full of flowers that one observer mistook it for a hearse (d’Annunzio adored flowers), he led them in a march on the harbour city of Fiume in Croatia, part of the defunct Austro-Hungarian Empire over whose dismemberment the victorious Allied leaders were deliberating in Paris. An army representing the Allies lay across the route. Its orders from the Allied high command were clear: to stop d’Annunzio, if necessary by shooting him dead. That army, though, was Italian, and a high proportion of its members sympathised with what d’Annunzio was doing. One after another its officers disregarded instructions. It was, d’Annunzio told a journalist later, almost comical the way the regular troops gave way, or deserted to follow in his train.

By the time he reached Fiume his following was some 2,000 strong. He was welcomed into the city by rapturous crowds who had been up all night waiting for him. An officer passing through the main square in the early hours of that morning saw it filled with women wearing evening dress and carrying guns, an image that nicely encapsulates the nature of the place – at once a phantasmagorical party and a battleground – during the fifteen months that d’Annunzio would hold Fiume as its Duce and dictator, in defiance of all the Allied powers.

Gabriele d’Annunzio was a man of vehement, but incoherent, political views. As the greatest Italian poet, in his own (and many others’) estimation, since Dante, he was il Vate, the national bard. He was a spokesman for the irredentist movement, whose enthusiasts wished to regain all those territories which had once been, or so they claimed, Italian, and which had been left irredenti (unredeemed) when Italians liberated themselves from foreign rulers in the previous century. His overt aim in coming to Fiume had been to make the place, which had a large Italian population, a part of Italy. Within days of his arrival it became evident this aim was unrealistic. Rather than admitting defeat, d’Annunzio enlarged his vision of what his little fiefdom might be. It was not just a patch of disputed territory. He announced that he was creating there a model city-state, one so politically innovative and so culturally brilliant that the whole drab, war-exhausted world would be dazzled by it. He called his Fiume a ‘searchlight radiant in the midst of an ocean of abjection’. It was a sacred fire whose sparks, flying on the wind, would set the world alight. It was the ‘City of the Holocaust’.

The place became a political laboratory. Socialists, anarchists, syndicalists, and some of those who had begun, earlier that year, to call themselves fascists, congregated there. Representatives of Sinn Féin and of nationalist groups from India and Egypt arrived, discreetly followed by British agents. Then there were the groups whose homeland was not of this earth: the Union of Free Spirits Tending Towards Perfection who met under a fig tree in the old town to talk about free love and the abolition of money, and YOGA, a kind of political-club-cum-street-gang described by one of its members as ‘an Island of the Blest in the infinite sea of history’.

D’Annunzian Fiume was a Land of Cockaigne, an extra-legitimate space where normal rules didn’t apply. It was also a land of cocaine (fashionably carried in a little gold box in the waistcoat pocket). Deserters and adrenalin-starved war veterans alike sought a refuge there from the dreariness of economic depression and the tedium of peace. Drug dealers and prostitutes followed them into the city: one visitor reported he had never known sex so cheap. So did aristocratic dilettantes, runaway teenagers, poets and poetry lovers from all over the Western world. Fiume in 1919 was as magnetic to an international confraternity of discontented idealists as San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury would be in 1968; but, unlike the hippies, d’Annunzio’s followers intended to make war as well as love. They formed a combustible mix. Every foreign office in Europe posted agents in Fiume, anxiously watching what d’Annunzio was up to. Journalists crammed the hotels.

D’Annunzio was already a bestselling novelist, a revered poet, and a dramatist whose premieres were attended by royalty and triggered riots. Now he boasted that in Fiume he was making an artwork whose materials were human lives. Fiume’s public life was a nonstop street-theatre performance. One observer likened life in the city to an endless fourteenth of July: ‘Songs, dances, rockets, fireworks, speeches. Eloquence! Eloquence! Eloquence!’

By the time his occupation of Fiume came to an end, d’Annunzio’s dream of an ideal society had deteriorated into a nightmare of ethnic conflict and ritualised violence. For over a year it suited none of the great powers to bestir themselves to eject him, but when, eventually, an Italian warship arrived in the harbour and bombarded his headquarters, he capitulated after a five-day fight. But for the duration of his command, Fiume was – precisely as he had intended it should be – the stage for an extraordinary real-life drama with a cast of thousands and a worldwide audience, one in which some of the darkest themes of the next half-century’s history were announced.

D’Annunzio believed he was working to create a new and better world order, a ‘politics of poetry’. So did observers from every point on the political spectrum, from the conservative nationalists who eagerly volunteered to join his Legion, to Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, who sent him a pot of caviar and called him the ‘only revolutionary in Europe’. His followers saw Fiume as a place where life could begin afresh – rinsed clean of all impurities, freer and more beautiful than ever before. But the culture created there rapidly took on a character which, seen in retrospect, is hideous. Black uniforms decorated with lightning flashes which made malign supermen of their wearers; military spectacles staged as though they were sacred rites; a cult of youth which degenerated into licensed delinquency; the bullying of ethnic minorities; the never-ending sequence of processions and festivals designed to glorify an adored leader: all of these phenomena are now recognisable as typical of the politics, not of poetry but of brute power. Later, Benito Mussolini encouraged the writing of a biography of d’Annunzio entitled The John the Baptist of Fascism. D’Annunzio, who saw the fascist leader as a vulgar imitator of himself, was not happy with the suggestion that he was a mere harbinger, preparing the way for Mussolini’s Messiah. But though d’Annunzio was not a fascist, fascism was d’Annunzian. The black shirts, the straight-armed salute, the songs and war cries, the glorification of virility and youth and patria and blood sacrifice, were all present in Fiume three years before Mussolini’s March on Rome.

A great deal has been written about the economic, political and military circumstances in which fascism and its associated political creeds flourished. D’Annunzio’s story provides a lens through which to examine those movements from another angle, to identify their cultural antecedents, and the psychological and emotional needs to which they pandered. To watch d’Annunzio’s trajectory from neo-Romantic young poet to instigator of a radical right-wing revolt against democratic authority is to recognise that fascism was not the freakish product of an exceptional historical moment, but something which grew organically out of long-established trends in European intellectual and social life.

Some of those trends were apparently unexceptionable. D’Annunzio was a man of broad and deep culture, thoughtful, widely read in the classics and in modern literature. He spoke for Beauty, for Life, for Love, for the Imagination (his capitals) – all of which sound like good things. Yet he helped to drag Italy into an unnecessary war, not because he believed it would bring any advantage but because he craved cataclysmic violence. His adventure in Fiume fatally destabilised Italy’s democracy, and opened the way for all the bombast and thuggery of fascism. He prided himself on his gift for ‘attention’, for fully experiencing and celebrating life’s abundance. ‘I am like the fisherman who walks barefoot over a beach uncovered at ebb tide, and who stoops, again and again, to identify and gather up whatever he feels moving under the soles of his feet.’ He posed as a new St Francis, lover of all living things. Yet his wartime rants are, in every sense, hateful. Italy’s enemies are filthy. He ascribes grotesque crimes to them. He calls out for their blood.

‘His gift for pleasing is diabolical,’ wrote Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. Even people who heartily disapproved of d’Annunzio found him irresistible. Similarly, reprehensible though the Europe-wide fascist movements were (and are), history demonstrates the potency of their glamour. To guard against their recurrence we need not just to be aware of their viciousness, but also to understand their power to seduce. D’Annunzio was never as supportive of fascism as Mussolini liked to make out. He jeered at the future Duce as a cowardly windbag. He despised Hitler too. But it is certainly true that his occupation of Fiume drastically undermined the authority of Italy’s democratic government, and so indirectly enabled Mussolini’s seizure of power three years later; that both Mussolini and Hitler learned a great deal from d’Annunzio; and that an account of d’Annunzio’s life and thought amounts to a history of the cultural elements that eventually came together, in the two decades following d’Annunzio’s annexation of his City of the Holocaust, to ignite a greater and more terrible holocaust than any he had ever envisaged.

The poet was fifty-six years old when he set out for Fiume, as notorious for his debts and duels and scandalous love affairs as he was celebrated for his wartime exploits and his literary gifts. A plane crash had left him blind in one eye, and, as he embarked on his great adventure, he was so weakened by an alarmingly high temperature that he could barely stand (something not to be taken lightly during a period when some fifty million people died of Spanish flu).

Small, bald, with narrow sloping shoulders and, according to his devoted secretary, ‘terrible teeth’, he was unimpressive to look at, but the long tally of his lovers included the ethereally lovely Eleonora Duse, one of the two greatest actresses in Europe (Sarah Bernhardt was her only rival), and he could manipulate a crowd as easily as he could entice a woman.

Poets nowadays are of interest only to a minority. But d’Annunzio was a poet, novelist and playwright at a time when a writer could attract a mass following, and deploy significant political influence. On the opening night of his play Più Che l’Amore (More Than Love) there were calls for his arrest. After the premiere of La Nave (The Ship) the audience spilled out of the theatre and processed through the streets of Rome intoning a line from the play, a call to arms. When he gave readings, agents of foreign powers attended, fearful of his influence. When he wrote polemical poems, Italy’s leading newspaper cleared the front page and published them in full.

Italy was a new nation. Its southern half (the Bourbon Kingdom of the Two Sicilies) was annexed to the northern kingdom of Piedmont two and a half years before d’Annunzio’s birth. He was seven years old in 1870 when the French withdrew from Rome and the new country was complete. The heroes of the Risorgimento had made Italy. Now someone had to ‘make Italians’ (the phrase recurs in the political rhetoric of the period). D’Annunzio, after spending much of his twenties writing erotic lyrics in archaic verse-forms and Frenchified fiction, accepted the task. Goethe in Germany and Pushkin in Russia had been celebrated, not just as authors of fine literature, but as the creators of a new national culture. So would d’Annunzio be. ‘The voice of my race speaks through me,’ he claimed.

He was much admired by his peers. In his twenties he was one of the acknowledged leaders of the aesthetes. As he matured he wrote works which won admiration not only from his own generation, but also from his younger contemporaries. James Joyce called d’Annunzio the only European writer after Flaubert (and before Joyce himself) to carry the novel into new territory, and ranked him with Kipling and Tolstoy as the three ‘most naturally talented writers’ to appear in the nineteenth century. Proust declared himself ‘ravi’ by one of his novels. Henry James praised the ‘extraordinary range and fineness’ of his artistic intelligence.

But though he was an author first and foremost, d’Annunzio was never solely a man of letters. He wanted his words to spark uprisings and set nations ablaze. His most famous wartime exploits were those occasions when he flew over Trieste or Vienna, dropping not bombs (although he dropped those too), but pamphlets. For d’Annunzio, writing was a martial art.

He was a brilliant self-publicist. He associated himself with Garibaldi, the romantic hero of the Risorgimento, whose image – poncho, red shirt, the dash of the guerrilla fighter combined with the integrity of a secular saint – was as important to the cause of Italian unity as his military prowess. D’Annunzio borrowed the lustre of figures from the past: he also identified himself with the dynamism of the future. He had himself photographed alongside torpedo boats and aeroplanes and motor cars – sleek, trim and modern from his gleaming bald pate to the toes of his patent-leather boots. Looking back, in his years of retirement, he saw exactly what had been his greatest strength as a politician. ‘I knew how to give my action the lasting power of the symbol.’ The hero of his first novel learns that: ‘One must make one’s life as one makes a work of art.’ D’Annunzio himself worked ceaselessly on the marvellous artefact that was his own existence.

He made canny use of the brand new mass media. As a young man he was a prolific hack, pouring out reviews and gossip and fashion notes and quasi-autobiographical sketches. His more earnest-minded friends thought he was debasing himself, but he wrote that the seed of an idea, sown in a journal, would germinate and bear fruit in the public consciousness more quickly and surely than one planted in a book. He describes one of his fictional alter egos as being drawn to his public as a predator is drawn to its prey.

Reaching a mass audience, d’Annunzio became a new kind of public figure. The first television broadcasts were made only in the last years of his life, but his influence was akin to that of a modern mass-media pundit. Instead of looking up the social scale and the political hierarchy, seeking endorsement from the ruling class, he looked to the people, turning popularity into power. As the historian Emilio Gentile has put it, what fascism took from Fiume was not a political creed but ‘a way of doing politics’. That way has since become almost universal.

In December 1919, d’Annunzio called for a referendum in Fiume. The people were to decide whether he was to stay and rule them, or to be expelled from the city. He waited for the result of the vote sitting in a dimly lit restaurant, sipping cherry brandy with his supporters. He told them about a life-size wax effigy of himself that, so he claimed, was in a Parisian museum. Once his present adventure was concluded, he said, he would ask to be given the figure and seat it by the window of his house in Venice, so that gondoliers could point it out to tourists. He was aware that someone like himself had two existences, one as a private person, the other as a public image. He knew that his celebrity could be used – to amuse trippers, to make himself some cash, to boost an army’s morale, perhaps even to overthrow a government.

D’Annunzio’s story is worth telling for reasons beyond his great talent and his life’s drama, lurid and eventful though it is. It illustrates a strand of cultural history which has its apparently innocuous origins in the classical past, passes through the marvels of the Renaissance and the idealism of early nineteenth-century Romanticism, but which leads eventually to the jackboot and the manganello, the fascist club.

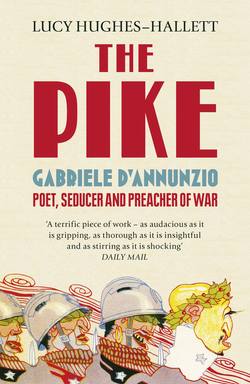

D’Annunzio read voraciously in several languages. He was adept at reviving neglected ideas whose time had come round again and he could spot a developing trend at the very moment of its formation. It is hard to find a cultural fad of the late nineteenth or early twentieth century which was not explored in his work. His flair for sensing what was new and influential moved Romain Rolland (a friend who became an enemy) to liken him to a pike, a predator lurking ‘afloat and still, waiting for ideas’. He was repeatedly accused of plagiarism, with some justice. He was a brilliant pasticheur, adopting and adapting the techniques of each new writer whose work impressed him. He wrote like Verga, he wrote like Flaubert, he wrote like Dostoevsky. But more intelligent critics noticed that he didn’t imitate so much as appropriate. When he saw something that could nourish his intellect drifting by on the current, he would snap at it, pike-like, and swallow it, and send it forth again better expressed.

He borrowed, but he also anticipated. Before Freud, he was fully aware of the nature of the excitement he derived from sleek machinery: the prow of a metal warship, he wrote, is ‘a monstrous phallic elongation’. Reading Nietzsche in the 1890s he recognised ideas already implicit in his own work. He had been modelling his verse on that of pre-Renaissance poets for a quarter of a century by the time Ezra Pound began to imitate the troubadours. He was writing about priapic fauns and pre-pagan ceremonies three decades before Nijinsky and Stravinsky sparked off a riot with The Rite of Spring. In 1888, a full two decades before Marinetti proclaimed a ruthless new machine-age aesthetic in the ‘Futurist Manifesto’, d’Annunzio wrote an ode to a torpedo. He loved motor cars and telephones and aeroplanes and machine guns. Marinetti’s manifesto is full of unacknowledged d’Annunzian sentiments, including the notion that civil society was so foul that only war could cleanse it.

His politics were as eclectic as his cultural tastes. He was not a party man, having far too lively a sense of his unique importance to subscribe to a programme imposed by others. Besides, the period when he was most active politically was a time when groups which would, only months after he marched on Fiume, separate out into mutually hostile phalanxes, made common cause, the extremes meeting to oppose the centre. Nationalism (now identified with the right) and syndicalism (leftist) were, according to one of d’Annunzio contemporaries, alike ‘doctrines of energy and the will’. Both preferred violence to negotiation; both understood the political process in terms, not of reason, but of myth. In a ‘venal and materialist society’ of democratic ‘stockbrokers and chemists’, they were heroic: the ‘only two aristocratic tendencies’. What mattered to d’Annunzio, and to the fascists after him, was not a theoretical programme, so much as style, vitality, vigour.

In Fiume, d’Annunzio drew up a constitution for his little state. ‘The Charter of Carnaro’, as he called it, is in many ways a remarkably liberal document. It promised universal adult suffrage and absolute legal equality of the sexes. Socialists applauded it. But in the 1920s it was hailed as ‘a blueprint of the fascist state’.

There is an acceptable d’Annunzio, who writes lyrically about nature and myth, and there is an appalling d’Annunzio, the warmonger who calls upon his fellow Italians to saturate the earth with blood, and whose advocacy of the dangerous ideals of patriotism and glory opened the way for institutionalised thuggery. Those who admire the former have often tried to ignore, or even deny, the existence of the latter. After the fall of Mussolini it became conventional to suggest either that d’Annunzio could not really have had any sympathy for fascism, because he wrote such beautiful poetry, or – conversely – that because his politics were deplorable, his poetry cannot really be any good. I contest both arguments. The two d’Annunzios are one and the same.

D’Annunzio knew exactly how ghastly conflict could be. As a young man he visited hospitals out of curiosity. He was an attentive nurse to his mistresses when they fell ill, loving them the most, he told them, when they were suffering or near death. In wartime he spent weeks at the front, witnessing the slaughter, smelling the unburied corpses. He made careful notes about wounds, and the effects of decomposition on the bodies of his dead friends. In his wartime oratory he used the word ‘sacrifice’ over and over again in knowing reference to religious fables (pagan and Christian) where young men were killed that the wider community might benefit. When two fighter pilots of whom he was fond went missing in 1917 he wrote in his private diary that he devoutly hoped they were dead.

He was one of the cleverest of men, but also one of the least empathetic. He was as ruthless and selfish as a baby. ‘He is a child,’ wrote the French novelist, René Boylesve, ‘he gives himself away with a thousand lies and tricks.’ Child-like, he saw others only in relation to himself. In love, he was adoring, but once he had tired of a woman he ceased to think about her. He was an excellent employer (though far from punctilious about paying salaries). He was moved by the sweetness of small children. He was very kind to his dogs. But the woman who brought in his meals, he once wrote, was no more to him than a piece of furniture, a cupboard on feet.

One of his most famous poems is about the Abruzzese shepherds who could be seen at summer’s end traipsing along the beaches, robed and bearded like biblical patriarchs, their woolly charges churning around them like warm surf. It is a lovely lyric, tender and grand; but to those who know d’Annunzio it cannot be read as harmless pastoral. He wrote often about the sheep herded before dawn through the sleeping streets of nineteenth-century cities, their wool eerily silvered by the moonlight – a commonplace sight which few other writers notice. To him the animals weren’t pretty reminders of the countryside. They were hosts of creatures on their way to be slaughtered. So were armies. The thought didn’t appal him. In 1914, three years before his British contemporary Wilfred Owen made the same comparison, d’Annunzio was likening the herds of bullocks who churned up the roads of northern France, driven to the front to feed the army, to the trainloads of soldiers going the same way. Like Owen, d’Annunzio knew that in war men died as cattle. Unlike Owen, he considered their death not only dulce et decorum, sweet and fitting, but sublime.

One evening in Rome in May 1915, d’Annunzio was chatting lightly in his hotel room with a couple of acquaintances. One was the sculptor Vincenzo Gemito, the other was the Marchese Casati (with whose wife – ‘the only woman who could astonish me’ – d’Annunzio had a long amitié amoureuse). Then, this agreeable interlude over, he stepped out onto his balcony to deliver one of his most incendiary speeches, urging the crowds beneath his window to transform themselves into a lynch mob. ‘If it is considered a crime to incite citizens to violence then I boast of committing that crime.’ Three paces and a window pane separated the sphere in which he was an urbane socialite and man of letters from that in which he was a frenzied demagogue calling upon his countrymen to murder their elected representatives and to drench the soil of Europe with blood. Both personae are genuine. In writing about him I have tried to find a form which does justice to them both.

D’Annunzio’s must be one of the most thoroughly documented lives ever lived. He had a notebook in his pocket at all times. Those notebooks were his precious raw material. Their contents reappeared in his poems, his letters, his novels. When he flew (or rather was flown – he never learned to pilot himself) he took a specially bought fountain pen with him so that he could jot down his impressions even while dodging anti-aircraft fire. He noted the clothes and sex appeal of the women he met so immediately that it seems he must have been reaching for his book even before they turned away. Eating alone at home, he wrote down a description of the maid as she served him his lunch. A discriminating eater, he also made notes on the asparagus.

His works are full of descriptions of sex so candid they still startle. In his morning-after letters he would describe back to a lover the pleasures they had enjoyed, an intimate kind of pornography which was also an aide-mémoire for himself and, often, the first draft for a fictional scene. We know in enormous detail what d’Annunzio did in bed, or on the rug before a well-banked-up fire (he felt the cold dreadfully), or in woods and secluded gardens on summer nights. We know he liked occasionally to play at being a woman, pushing his penis out of the way between his thighs. We know how much he enjoyed cunnilingus, and that he therefore preferred a woman to be at least five foot six inches tall, or, failing that, to wear high-heeled shoes, so that when he knelt before her his mouth comfortably met her genitals. We have his descriptions not only of his lovers’ outward appearances but of the secret crannies of their bodies, of the roofs of their mouths, of the inner whorls of their ears, of the little hairs on the back of a neck, of the scent of their armpits and their cunts.

The notebooks, d’Annunzio’s enormous literary output, and his even larger correspondence, have allowed me to show the man’s inside: his thoughts, tastes, emotions and physical sensations; how moved he was by the pathos of a pile of dead soldiers’ boots; how he relished the slithery warmth of a greyhound’s coat under his hand. And because he was a public figure for over half a century, I have been able to draw on dozens of others’ accounts of him and his doings to show his outside as well. This book has many viewpoints. And because d’Annunzio’s life, like any other, was complex, they sometimes contradict each other. An acquaintance, seeing him in Florence, leaning on the stone parapet over the River Arno one grey November day, noticed the elegance of his raincoat (he was always dapper) and tactfully refrained from greeting him, supposing him to be absorbed in the composition of a poem. From his own account, though, we know he could think of nothing but of whether his mistress would shortly appear, and what he would do with her once he had got her back to the room he kept for their assignations, where he had already stowed scented handkerchiefs behind cushions and strewn the bed with flowers.

I have made nothing up, but I have freely made use of techniques commoner in fiction-writing than in biography. I have not always observed chronological order; the beginning is seldom the best place to start. Time’s pace varies. I have raced through decades and slowed right down, on occasion, to record in great detail a week, a night, a conversation. To borrow terms from music (and one of the themes of d’Annunzio’s life to which I have not had space to do full justice is his musical connoisseurship) I have alternated legato narrative with staccato glimpses of the man and fragments of his thought.

I have tried to avoid the falsification inevitable when a life – made up, as most lives are, of contiguous but unconnected strands – is blended to fit into a homogeneous narrative. In Venice in 1908 for the premiere of The Ship, d’Annunzio attended banquets and civic ceremonies in his honour, delivering convoluted speeches full of noble sentiments and incitements to war. He records, though, that ‘between one acclamation and another’ he spent a great deal of time hunting for the perfect present for his mistress. An antique emerald ring – which he could certainly not afford (he was at this period unable to go home for fear of his creditors) – satisfied him, but there was still the question of a box to put it in. He visited half a dozen places before finding the very thing – a pretty little casket in green leather (to match her eyes) in the shape of a miniature doge’s hat. I aim to do justice both to the man pontificating at the banquet, and the man fossicking through curio shops.

Two images help to describe my method. The first dates from 1896, when d’Annunzio was thirty-three, and staying in Venice to be near Eleonora Duse. There he came to know Giorgio Franchetti, who had recently bought the Ca’ d’Oro, the most fantastical and ornate of all the palaces along the Grand Canal, and was restoring it to its fifteenth-century Venetian-Moorish splendour. Franchetti was working himself on the installation of a mosaic pavement, crawling, covered with sweat and stone dust, over the varicoloured expanse of rare stones with slippers strapped to his knees. There d’Annunzio would join him, laying tiny squares of porphyry and serpentine in the fresh cement. Placing comments and anecdotes alongside each other like the tesserae in a pavement, my aim has been to create an account which acknowledges the disjunctions and complexities of my subject, while gradually revealing its grand design.

Another image comes from Tom Antongini, who knew and served d’Annunzio well for thirty years as his secretary, agent, personal shopper, and, in the sexual sphere, Leporello to his Don Giovanni. Antongini described the hectic months d’Annunzio spent in Paris in 1910 as ‘kaleidoscopic’. In an old-fashioned kaleidoscope, fragments of jewel-bright glass are rearranged as the cardboard tube is twirled – the same parts, a changing pattern. Images and ideas recur in d’Annunzio’s life and thought, moving from reality to fiction and back again: martyrdom and human sacrifice, amputated hands, the scent of lilac, Icarus and aeroplanes, the sweet vulnerability of babies, the superman who is half-beast, half-god. I have laid out the pieces: I have shown how they shift.

D’Annunzio has been much disliked. His contemporary, the philosopher and historian Benedetto Croce, said he was ‘steeped in sensuality and sadism and cold-blooded dilettantism’. Tom Antongini, who was fond of him, wrote that he ‘has been accused of polygamy, adultery, theft, incest, secret vices, simony, murder, and cannibalism … in short, Heliogabalus is his master in no particular’. When, on his death in 1938, there was discussion in the British Foreign Office as to whether it would be in order to offer official condolences, the proposal was vehemently opposed by Lord Vansittart, who called him ‘a first-class cad’. This hostility persists. Mark Thompson, the outstanding historian of Italy’s part in the Great War, writes with judicious moderation about General Cadorna, the Italian commander-in-chief who sent hundreds of thousands of soldiers to a certain death. Thompson’s tone, in describing Mussolini and the beginnings of fascism, is temperate. But these are the words he uses of d’Annunzio: ‘odious’, ‘vicious’, ‘psychotic’.

I have been sparing of such language. I am a woman writing about a self-styled ‘poet of virility’ and a pacifist writing about a warmonger, but disapproval is not an interesting response. D’Annunzio cannot be dismissed as being singularly hateful or crazy. He helped to talk his country into an unnecessary war, and the views he expressed, then and throughout his life, are frequently abhorrent. But to suggest that his thinking was aberrant is to deny the magnitude of the problem he presents. Over and over again throughout the Great War, d’Annunzio called upon teenage conscripts, very few of whom had any idea what Italy’s war aims were, to die because the blood of those who had already died called out to them from the earth to emulate their ‘sacrifice’. At the time of writing a very similar thought – less floridly expressed – is regularly advanced to justify the continuation of the war in Afghanistan. Many have died. To admit that the fighting is futile, and put a stop to it, would be to betray them. So more must die. This reasoning may be odious (I consider it so). But if to be ‘psychotic’ is to think in a way few healthy people think, then it is not psychotic. It is all too normal.

In 1928, Margherita Sarfatti published a biography of her lover, Mussolini. In it she praised d’Annunzio for having ‘prophesied, preached and fought the war’ (preaching war being, in fascist opinion, a laudable practice) and hailed the poet as having given expression to ‘an arrogant, knightly, derisive, fascinating and cruel spirit that belongs to the immortal youth of fascism’. Later Sarfatti, who was Jewish, would have to leave Italy hastily in order to escape that ‘fascinating and cruel spirit’, but for the time being she adored it, and admired d’Annunzio, whose work seemed to her to be as full of ‘daring, hope, greatness and limitless faith’ as the sound of the blackshirts belting out popular songs as they converged on Rome in October 1922.

In the first winter of the Great War, d’Annunzio was living in France, and made several trips to the front as a privileged observer. There he saw – or pretended to have seen – dead soldiers bound upright, to stakes, in groups of ten. At the time, Mussolini had only recently left the Italian Socialist Party and had yet to find a new following. But already d’Annunzio had found an image all too hideously symbolic of the militarism which he himself so enthusiastically approved, and of the political creed which would shortly grow out of it. Those bloody clumps of upstanding corpses reminded him of an emblem frequently shown on Roman coins, one which would soon, once again, be omnipresent in Italy, that of a bundle (a fascio) of rods tied around an axe. The axe signified the law’s power over life and death. The bundled rods represented the gathering of powerless individuals into a single powerful entity, a ‘fascist’ state.