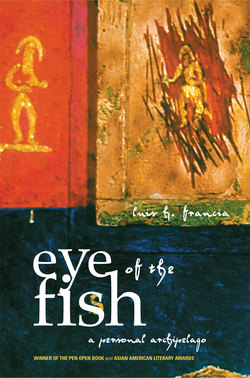

Читать книгу The Eye Of The Fish - Luis H. Francia - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWAKE UP. STOP THIS BUS. NOW. Bladders speak and, by the roadside, sing their trilling song. Some of my fellow passengers start pointing their cameras and clicking. There on our right, carved from a cliff face some 150 meters away looms the gigantic bust of Ferdinand Marcos, a Mt. Rushmore-like construction. The men take a leak in the bushes, right under the dead dictator’s humongous nose, though his nostrils fail to quiver. The stone face reflects not just every tyrant’s wish to be forever memorialized but the unsettling depth to which personality matters in this archipelago’s social and political landscape, the way it obliterates abstract ideology by embodying the desire for redemption in the solidity of human flesh, in someone seemingly heroic or even godlike.

Carving up this mountain has meant the dislocation of the Ibaloi, one of several tribes collectively known as Igorots who have lived in these mountains for centuries. The Ibaloi’s ancestral spirits, it is said, haunt the area, mourning for a lost kingdom. Dipped in melancholy, these peaks teem with dispossessed souls, a legacy of warfare, of social upheaval. Benedictions passed on, we resume our journey. After we’ve gone a bit further, I see, from a bend in the highway, Marcos somehow looming larger, a grey-shaped gorgon, something like resentment in his eyes.

The bus squeezes through Dalton Pass, which cuts across the Sierra Madre range. Its eroded mountainsides, oozing desolation, resemble a pack of dogs with mange. A year ago, an earthquake origamied this area, crushing vehicles and burying their occupants. These slopes are now their nature-wrought mausoleums, grander and sadder than anything any funerary merchant could have dreamt of. Only flame trees, now in full flower, provide a welcome fugue to the drab, desert colors, red bursts against a searingly blue sky. Their flowers once signaled the start of the headhunting season by the Ilongots, the Igorot tribe indigenous to this area. Or so I had been told as a child, scared by stories of how unwary travellers or campers would be set upon by tribal headhunters and decapitated, the heads carried away as trophies. The Ilongots don’t do much headhunting now, their fierceness of spirit—a spirit that once matched and revered that of the mountains—now much diminished.

The bus roars through small towns, corrugated iron roofs glinting in the sun, dogs lolling about on the road, barely getting out of the way of the thundering behemoth. It stops occasionally in front of some homes, the driver honks the horn, a person appears in a doorway, and the conductor flings packets of letters out the window, and again we roar away in a cloud of dust. After these rites of passage we get into the town of Banaue, heat giving way to the chill of a mountain evening.

Hotel room with a view: a valley, wooded peaks, and a few rice terraces. The terraces, the balding resident manager laments that night, are not as tidy as they used to be. The young folk are going down to Manila to look for work. His emphasis on the word “down” implies a spiritual as well as a physical fall. Early the next morning, the world rattles briefly, frighteningly, waking me up. Since the quake, Banaue has been experiencing tremors, though it was spared devastation, unlike Baguio City, southwest of here. Banaue elders say Baguio suffered because of the erosion of its traditional values. In contrast, Banaue has no bars, except at the hotel, no discos, massage parlors, or shopping malls. The elders believe land in Banaue is sacred, and Nature will not destroy sacred soil.

The vaster valleys of rice terraces that the region is know for aren’t in the town of Banaue, however, but in the nearby barrio of Batad. The lamentations of the hotel manager notwithstanding, Batad’s terraces appear to be well maintained, nestled in a bowl formed by several mountains. To get there has meant trekking on a narrow trail, with a precipitous drop on one side. One false step and I hurtle down, a brown Icarus punished. An Ifugao woman works on a terraced slope, bending over and weeding the plot, her tattooed arms working steadily. Amphitheater-style, the terraces enclose Batad and lie serenely green under the sun, each one a rectangular enclosure bounded by rock walls, the summit of each series heavily wooded to hold down rainwater and prevent topsoil from eroding the terraces.

Batad itself is a neat cluster of triangularly roofed thatched huts built on stilts, with narrow entrances that make it difficult for both wild beast and human foe to enter. I rest under the eaves of one hut and look up: a row of pig skulls contemplates me—a sign of many feasts and rituals. The skulls present an eerie but strangely calming sight: this is a real village, postcard pretty from afar but up close filled with the intricate details of living.

The rice terraces soar mightily toward an azure sky, giant step upon giant step, carved from the earth two millennia ago. These imposing structures, if placed end to end, would stretch for fourteen thousand miles, or halfway around the world. Their reach is grander than that, of course, straddling the centuries, challenging our notions of modernity, and bearing witness to the lives that have unfolded here. What did the Spanish who saw these vast networks of terraces think of ? They must have realized that a people who could carve whole mountains would not be easy to conquer. While the conquistadors may have brought down the Inca empire in the Andean highlands, they hardly made any headway up here, in their more than three hundred years in the archipelago, on the contrary losing quite a few heads along the way.

In these Cordilleran cathedrals of rock and earth, in the bent-down figures working the fields, can be seen gestures of reverence and worship as well as the need to triumph. The terraces interweave culture and history in a place where rice plays a central role. Almost a deity in its power over life and death, rice is symbolized here by the bulol, the ubiquitous carved wooden rice god, in which highlander and grain are mystically conjoined. Squatting, with arms resting on knees, the guardian gazes cooly on the world, on us, measured and measuring.

The terraces themselves make clear that history here was simultaneously an act of obeisance and hubris. The terraces led up to the sky itself, challenging the gods, but they led down as well. And they transformed the peaks into altars—and listening posts. If you had to appease the gods, you had to know how to tickle their vanity, and sometimes how to confuse them as well—a delicate, balancing act. Those who could do it best were the tribe’s shamans, embodying both oracle and fool, seer and standup comic. Too bad they didn’t wash with the Christian god of uptight Iberian friars, a god who didn’t know how to have fun, except of course at the expense of his darker charges.

To the Cordilleran highlanders, how useless it would have been to build structures other than those meant for the daily business of living and planting. Nothing could compete with the grandeur of these mountains that reminded them of their own physical frailty, and the constant need for both humility and cunning in the face of heaven’s power. By the coastal areas it was different, or rather had become different: the sense of self, of culture, may have been akin to the brethren in the highlands but the Spanish—the European—sense of narrative, of linear history ever onward and forward, stressed the creation of visible symbols that would attest to the ascendance of man over space and time. The stone churches that the Catholic faith prompted converted lowland Filipinos to build came to embody the colonized’s own sense of history, substituting one set of public, more grandiose symbols for another. In the lowlands, as native bequests grew fainter and fainter, the need for preserving post-Magellanic artifacts grew correspondingly. And so the dominant feeling among the lowlanders, and I was one, was that colonial history was all we had, tying us, at the same time that it made us supremely adaptable, to the demands of an imperious West. It was easy for the glib foreigner to view local culture through a jaundiced eye, dismissing it as a pale imitation of a Western model. Where were our Borobudurs, our Angkor Wats? Indeed, measured against our regional neighbors, Filipinos seemed to be less Asian.

And yet the dissolution of ties to a pre-1521 culture could never be complete, being too much in the blood and memory of a race, even if only vestigially. That inchoate awareness was revealed obliquely in the way that the Igorots, along with the Muslims in Mindanao, were often referred to as “genuine” Filipinos. This thinking assumed that the colonized and Christianized lowlanders were less than Filipino. But the term “Filipino” was itself problematic, derived from the name of Felipe II, the sixteenth-century Spanish king who never saw the archipelago of more than seven thousand islands named in his honor. In that faraway royal court, did illustrious, unwashed Felipe ever dream of these islands, a Christian wedge in a Muslim world, its wooden crosses raised against the Crescent, its friars’ prayers countermanding the call of the muezzins?

Trekking back from Batad to the main road, I look behind and notice a mongrel bitch following me, her teats no longer heavy with milk. Every time I stop, she stops, regarding me as intently as I regard her but keeping her distance. Each time I resume, so does she, keen on keeping me in sight. From time to time she is right at my heels, making no sound at all. I wonder if she is a benevolent dog spirit, attaching herself to me for my protection. Or perhaps it is the other way around. By the time we get to the road, she trots around me in a rite of encirclement. Speak, dog, tell your story. But she heads off in the opposite direction, disappearing around a bend, a silent emissary of the Cordilleras.

WAKE UP. STOP THIS BUS. NOW. Bladders speak and, by the roadside, sing their trilling song. Some of my fellow passengers start pointing their cameras and clicking. There on our right, carved from a cliff face some 150 meters away looms the gigantic bust of Ferdinand Marcos, a Mt. Rushmore-like construction. The men take a leak in the bushes, right under the dead dictator’s humongous nose, though his nostrils fail to quiver. The stone face reflects not just every tyrant’s wish to be forever memorialized but the unsettling depth to which personality matters in this archipelago’s social and political landscape, the way it obliterates abstract ideology by embodying the desire for redemption in the solidity of human flesh, in someone seemingly heroic or even godlike.

Carving up this mountain has meant the dislocation of the Ibaloi, one of several tribes collectively known as Igorots who have lived in these mountains for centuries. The Ibaloi’s ancestral spirits, it is said, haunt the area, mourning for a lost kingdom. Dipped in melancholy, these peaks teem with dispossessed souls, a legacy of warfare, of social upheaval. Benedictions passed on, we resume our journey. After we’ve gone a bit further, I see, from a bend in the highway, Marcos somehow looming larger, a grey-shaped gorgon, something like resentment in his eyes.

The bus squeezes through Dalton Pass, which cuts across the Sierra Madre range. Its eroded mountainsides, oozing desolation, resemble a pack of dogs with mange. A year ago, an earthquake origamied this area, crushing vehicles and burying their occupants. These slopes are now their nature-wrought mausoleums, grander and sadder than anything any funerary merchant could have dreamt of. Only flame trees, now in full flower, provide a welcome fugue to the drab, desert colors, red bursts against a searingly blue sky. Their flowers once signaled the start of the headhunting season by the Ilongots, the Igorot tribe indigenous to this area. Or so I had been told as a child, scared by stories of how unwary travellers or campers would be set upon by tribal headhunters and decapitated, the heads carried away as trophies. The Ilongots don’t do much headhunting now, their fierceness of spirit—a spirit that once matched and revered that of the mountains—now much diminished.

The bus roars through small towns, corrugated iron roofs glinting in the sun, dogs lolling about on the road, barely getting out of the way of the thundering behemoth. It stops occasionally in front of some homes, the driver honks the horn, a person appears in a doorway, and the conductor flings packets of letters out the window, and again we roar away in a cloud of dust. After these rites of passage we get into the town of Banaue, heat giving way to the chill of a mountain evening.

Hotel room with a view: a valley, wooded peaks, and a few rice terraces. The terraces, the balding resident manager laments that night, are not as tidy as they used to be. The young folk are going down to Manila to look for work. His emphasis on the word “down” implies a spiritual as well as a physical fall. Early the next morning, the world rattles briefly, frighteningly, waking me up. Since the quake, Banaue has been experiencing tremors, though it was spared devastation, unlike Baguio City, southwest of here. Banaue elders say Baguio suffered because of the erosion of its traditional values. In contrast, Banaue has no bars, except at the hotel, no discos, massage parlors, or shopping malls. The elders believe land in Banaue is sacred, and Nature will not destroy sacred soil.

The vaster valleys of rice terraces that the region is know for aren’t in the town of Banaue, however, but in the nearby barrio of Batad. The lamentations of the hotel manager notwithstanding, Batad’s terraces appear to be well maintained, nestled in a bowl formed by several mountains. To get there has meant trekking on a narrow trail, with a precipitous drop on one side. One false step and I hurtle down, a brown Icarus punished. An Ifugao woman works on a terraced slope, bending over and weeding the plot, her tattooed arms working steadily. Amphitheater-style, the terraces enclose Batad and lie serenely green under the sun, each one a rectangular enclosure bounded by rock walls, the summit of each series heavily wooded to hold down rainwater and prevent topsoil from eroding the terraces.

Batad itself is a neat cluster of triangularly roofed thatched huts built on stilts, with narrow entrances that make it difficult for both wild beast and human foe to enter. I rest under the eaves of one hut and look up: a row of pig skulls contemplates me—a sign of many feasts and rituals. The skulls present an eerie but strangely calming sight: this is a real village, postcard pretty from afar but up close filled with the intricate details of living.

The rice terraces soar mightily toward an azure sky, giant step upon giant step, carved from the earth two millennia ago. These imposing structures, if placed end to end, would stretch for fourteen thousand miles, or halfway around the world. Their reach is grander than that, of course, straddling the centuries, challenging our notions of modernity, and bearing witness to the lives that have unfolded here. What did the Spanish who saw these vast networks of terraces think of ? They must have realized that a people who could carve whole mountains would not be easy to conquer. While the conquistadors may have brought down the Inca empire in the Andean highlands, they hardly made any headway up here, in their more than three hundred years in the archipelago, on the contrary losing quite a few heads along the way.

In these Cordilleran cathedrals of rock and earth, in the bent-down figures working the fields, can be seen gestures of reverence and worship as well as the need to triumph. The terraces interweave culture and history in a place where rice plays a central role. Almost a deity in its power over life and death, rice is symbolized here by the bulol, the ubiquitous carved wooden rice god, in which highlander and grain are mystically conjoined. Squatting, with arms resting on knees, the guardian gazes cooly on the world, on us, measured and measuring.

The terraces themselves make clear that history here was simultaneously an act of obeisance and hubris. The terraces led up to the sky itself, challenging the gods, but they led down as well. And they transformed the peaks into altars—and listening posts. If you had to appease the gods, you had to know how to tickle their vanity, and sometimes how to confuse them as well—a delicate, balancing act. Those who could do it best were the tribe’s shamans, embodying both oracle and fool, seer and standup comic. Too bad they didn’t wash with the Christian god of uptight Iberian friars, a god who didn’t know how to have fun, except of course at the expense of his darker charges.

To the Cordilleran highlanders, how useless it would have been to build structures other than those meant for the daily business of living and planting. Nothing could compete with the grandeur of these mountains that reminded them of their own physical frailty, and the constant need for both humility and cunning in the face of heaven’s power. By the coastal areas it was different, or rather had become different: the sense of self, of culture, may have been akin to the brethren in the highlands but the Spanish—the European—sense of narrative, of linear history ever onward and forward, stressed the creation of visible symbols that would attest to the ascendance of man over space and time. The stone churches that the Catholic faith prompted converted lowland Filipinos to build came to embody the colonized’s own sense of history, substituting one set of public, more grandiose symbols for another. In the lowlands, as native bequests grew fainter and fainter, the need for preserving post-Magellanic artifacts grew correspondingly. And so the dominant feeling among the lowlanders, and I was one, was that colonial history was all we had, tying us, at the same time that it made us supremely adaptable, to the demands of an imperious West. It was easy for the glib foreigner to view local culture through a jaundiced eye, dismissing it as a pale imitation of a Western model. Where were our Borobudurs, our Angkor Wats? Indeed, measured against our regional neighbors, Filipinos seemed to be less Asian.

And yet the dissolution of ties to a pre-1521 culture could never be complete, being too much in the blood and memory of a race, even if only vestigially. That inchoate awareness was revealed obliquely in the way that the Igorots, along with the Muslims in Mindanao, were often referred to as “genuine” Filipinos. This thinking assumed that the colonized and Christianized lowlanders were less than Filipino. But the term “Filipino” was itself problematic, derived from the name of Felipe II, the sixteenth-century Spanish king who never saw the archipelago of more than seven thousand islands named in his honor. In that faraway royal court, did illustrious, unwashed Felipe ever dream of these islands, a Christian wedge in a Muslim world, its wooden crosses raised against the Crescent, its friars’ prayers countermanding the call of the muezzins?

Trekking back from Batad to the main road, I look behind and notice a mongrel bitch following me, her teats no longer heavy with milk. Every time I stop, she stops, regarding me as intently as I regard her but keeping her distance. Each time I resume, so does she, keen on keeping me in sight. From time to time she is right at my heels, making no sound at all. I wonder if she is a benevolent dog spirit, attaching herself to me for my protection. Or perhaps it is the other way around. By the time we get to the road, she trots around me in a rite of encirclement. Speak, dog, tell your story. But she heads off in the opposite direction, disappearing around a bend, a silent emissary of the Cordilleras.