Читать книгу The Eye Of The Fish - Luis H. Francia - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA COLD RAIN FORCES ME AND THE REST of the bus passengers to draw up the wooden window shutters. The night mist and city lights imbue Baguio City, the Cordilleras’ administrative and political capital, with a spectral appearance. During the early part of the twentieth century, the American colonial government sought relief here in Baguio from the intolerable summer lowland heat and humidity. Officials asked Chicago architect Daniel Burnham to draw up plans for a hill station, for a population that was estimated to grow from twenty Ibaloi households—the original inhabitants—to twenty thousand. Today, city dwellers number close to half a million, spread over fifty square kilometers of hills and pine-forested slopes.

Occupied by the Japanese and devastated during World War II, the city was quickly rebuilt after 1945, becoming once again the country’s summer capital. Burnham’s handiwork survives in the design of the city center, which includes a City Hall that looks much like Manila’s, a willow-fringed park (named after Burnham) with its boating lagoon, and a complex of roads leading to the city’s several districts and to points further north and east. In 1990, the city was devastated again, this time by the same earthquake that crumpled Dalton Pass. Several hotels collapsed, along with scores of residences, many of which were flimsily built squatters’ homes. The city’s funeral parlors were unable to handle the sudden increase in business, and so bodies were strewn around the parks, and the air was filled for weeks with the stench of death. The lowland press speculated on the city’s demise, but in little more than a year, Baguio had recovered, had started to attract visitors once again. How could it be otherwise? In these mountains, death by earthquake was a given, was a part of living.

I love this city, balm in childhood and adulthood, a much-needed refuge from Manila’s murderous premonsoon heat. Horseback rides at Wright Park, boating on Burnham’s artificial lake, walks on Session Road and up and down a city that sloped every which way—these were the sum and content of my childhood trips. As a boy coming to Baguio for family vacations, I would eagerly await the smell of pine to waft through the car windows, a smell that heralded a world different from the humdrum one of Manila. Today that scent has all but vanished, replaced by diesel fumes. Militarization in far-flung areas and the corresponding influx of the poor and the dispossessed, together with the lax enforcement of zoning and environmental laws, have resulted in trees being cut for fuel and building material.

On the wall of her apartment in Arlington, Virginia, my mother has a photograph of me—I must have been five years old then— together with my brothers and sisters, astride ponies in Wright Park. Riders and animals look docile, bemused. The ponies’ handlers— tough but gentle men, Igorots whose land this once was—are nowhere to be seen, shunted off camera. They were largely invisible to us, forming part of an exotic backdrop to our vacations. As a child I knew nothing of them, only that they were different from us, Other. I had no idea then that they had had a long history of resistance to foreign incursions. In Manila, my only encounters with them had been in the hunched forms of elderly Igorot women who went begging from door to door. For them to be on the coast, in the indifferent embrace and oppressive heat of Manila meant the abasement of a proud people, a culture exploited by and under siege from consumerism.

In the 1970s, however, spurred by the excesses of the Marcos regime and by militarization, the Cordilleras became once again a center of resistance to lowland oppression. Quiescent warrior traditions were revived, and the communist New People’s Army found a secure refuge in the mountains. The government in Manila realized that its hold up in the highland was shaky—had in fact always been shaky. Highland resistance to the Marcos regime reached its peak in the vigorous opposition to the proposed building of the Chico River dam, which would have inundated the ancient burial grounds of the Kalinga tribe. The Kalinga and the NPA formed a tactical alliance, but it was the military’s subsequent 1980 assassination of Macli-ing Dulag, a charismatic Kalinga chief, that provoked widespread outrage, ultimately forcing the cancellation of the plan to build the dam.

With the collapse of the Marcos regime in 1986, a lot of windows had been thrown open, to get rid of the musty air. And in Baguio, several well-known artists—who either had been born there or had chosen to live there and all of whom had lived in the West a while— began to meet informally, began to talk of what their art meant to them, began to think of themselves as a collective, as part of a nation perenially plagued by self-doubt, by uncertainty in the way it dealt with cultural issues. The result of these meetings was the formation of the Baguio Artists Guild.

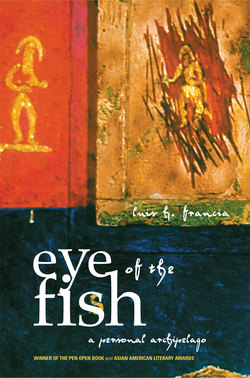

One of its prime movers and founders is Ben Cabrera, also known as Bencab. A tall, balding, bespectacled man, Bencab is a well-known painter and printmaker who had lived in London for fifteen years before deciding to return to the Philippines. He has settled here, away from the big-city sophistication and pace of both London and Manila. I had last seen Bencab in New York in the early 1990s, where he had had a one-man show that explored the quake that leveled Baguio. I visit him one afternoon, and as we sit in his studio sipping coffee and gazing out at the city, he tells me about his artistic odyssey.

Bencab is illustrative of the Filipino artist who had once looked to and lived in the bosom of the West, secure in the belief that he was where he should be, only to find that the journey West was really a journey East. That journey began in the 1960s when he was offered a job as an artist and illustrator with the Manila office of the United States Information Service. The job paid P250 a month, nothing today but a decent salary then. His tasks were pleasant enough, but the colonial-mindedness of the staff bothered Bencab. “Hindi ko masakyan [I couldn’t stand it],” he explains. “I remember this one writer—he had been with the service for a while—who was telling me how he felt about two officers. One was a white American, the other was a short, dark Filipino. This writer said, look at us, we’re so ugly. He could hardly wait to immigrate to the United States: If you worked for the service for fifteen years, the come-on was you could go to America.”

For the educated Christian Filipino like Bencab or myself, this racial self-hatred was very much a part of growing up. The unremitting emphasis in school was on ignoring inconvenient details like race, cultural geography, and a history of warfare, abuse, and suppression. At the Ateneo de Manila High School, speaking Tagalog—or the “dialect,” as it was referred to—was forbidden, as though the native tongue were a repository of dark, unmentionable secrets, an omnipotent mantra, that could slough off our Western conditioning like unwanted skin. The history we had been taught was one informed thoroughly by the West. Our own stories were deemed relevant only in relation to the Spanish and American colonial periods, and even then it was a history written from the point of view of the victors, presenting a benign view of colonialism. (I don’t recall a single instance at school when the term was even used.) In the process, our tongue, our own sense of it, had temporarily disappeared. The impact of such an education was all too evident, for example, in our sense of aesthetics. Whether expressed in the clothing we wore—Levis, Arrow shirts, Florsheim, Nike—or in the music we preferred—rock, disco, Latin, jazz—our (hi-fi and stereophonic) fidelity to and feel for Western pop culture had few equals. The end result? I was drenched in nostalgia for places in the West I had never been to.

In terms of earthly beauty, it was no different—let my face be done on earth as it is in heaven. The Catholic icons revered by most of the country—the weepy but beautiful Madonna; her pink-cheeked, plump Santo Niño, or Holy Child; Christ as a handsome, bearded, incandescent ascetic—bore little resemblance to the masses who prayed, wept, and often crawled at their feet. No doubt a large number of the devotees wanted to be lighter-skinned, to have aquiline noses, be a little taller. The fairer, the better; Spanish or Caucasian American mestizas were prized. And so the silver screen echoed the national preference. The language used in local films may have been Tagalog, but the matinee idols had noses and eyes of a distinctly European origin. So it puzzled me as a teenager when I saw hulking American servicemen on leave, strolling on Roxas Boulevard accompanied by petite dark women I considered unattractive, women I presumed worked in bars.

It wasn’t so much what these women did that bothered me and my friends, it was that they looked “native.” Mukhang chimay, we would say, or “servant-faced,” our ultimate put-down for those women who failed to meet the standards we took for granted. Dark skin meant servility, undesirability, the wrong class. By reminding me of the traditions I had been separated from, these women threatened to disrupt a seemingly well-ordered but actually fragile and narrow world. Only later did I acknowledge the stirrings of attraction for these non-Caucasian-looking women of the night

Bencab’s work at the USIS made him begin to see the absurdity of all this. He quit and joined a now-defunct daily The Manila Times. Beatriz Romualdez—a niece of Imelda Marcos who would later marry Henry, my oldest brother—was also with the paper as a writer. She had just opened a café on Mabini Street in the Malate district of Manila, called Café Indios Bravos. It included gallery space that she rented out to Bencab and some other painters. Living in quarters above the gallery, Bencab met Manila’s literati and a lot of foreigners at the café. “I was naïve then: We all were. It was the sixties, a lot of things coming up, the miniskirt”—he laughed at this unintended pun—“marijuana, the Beatles. And Indios was the place to be then.”

It was at Indios that Bencab met his wife, a friend of Beatriz’s named Caroline Kennedy. Originally from London, Caroline had a blonde patrician beauty; in the eyes of Indios regulars she represented the desired Western sexual avatar, one completely different from those dusky women desired by American servicemen. She was very sixties —decked out in beads and paisley prints—and, because she was the new blonde in town, eagerly pursued.

At the end of the 1960s, the Indios gallery closed even though Bencab’s first one-man show there had been very successful. People simply weren’t buying. He and Caroline, already a pair, moved to London. There, for the sum of £3.50, they had a registry wedding. Bencab described those early years in London as “very exciting, very exotic.” By the following year, 1970, he had had his first show at a gallery in Greenwich. He soon developed a clientele that included the movie actress Glenda Jackson and Harold Pinter. But he also developed a pain in his stomach. Thinking it was appendicitis, he went to his wife’s family doctor. The diagnosis? Bencab was tense. He had had an overdose of Caroline’s family. They were friendly but patronizing, with that peculiar upper-class English mix of proper behavior and snotty derisiveness. He missed Mabini Street, familiar places, the friendliness of his own people.

Shortly after the birth of their first child, Eleazar, in 1971, Bencab and Caroline returned to Manila. A year later, Marcos declared martial law. Though they were a much sought-after couple socially, when Eleazar started reciting martial law slogans, they decided to return to London in 1974. This time, having begun to accept his life abroad, Bencab liked London.

But people there never quite knew how to react to him. And where there was prejudice, even if not overt, there was usually ignorance as well. “Once they found out I was from the Philippines,” Ben recalls, “people would say, ‘Oh the Philippines. It’s hot there, isn’t it?’ Talking about the weather is neutral, you don’t really offend anyone.” But feelings would slip through now and then. “The nanny of Caroline’s sister’s kids, when she saw Eleazar, exclaimed, ‘Oh, he’s so brown, isn’t he? But we love him anyway.’ She was South African.”

Sometimes it was funny. “We were in Majorca, and one day Eleazar was throwing a tantrum, refusing to eat his food. My motherin-law reprimanded him, ‘You don’t know how lucky you are compared to your Asian brothers!’”

In London, Bencab quickly realized that if he followed what was current in Western art, he would always be a second-rate artist, since the impulse for such art didn’t come from within, wasn’t part of his skin. He started to go over his collection of Filipiniana that he had slowly built up over the years, a lot of it from colonial-era texts written by the English and the Americans. He thought, “How come Japanese prints from the Edo period, works that were uniquely Japanese, came to be appreciated? There was a conscientious shift in me, to look to Filipino material.”

“The first piece I did was Portrait of a Servant Girl, which was based on a turn-of-the-century photo. I wanted to show both the servility of the Pinoy and the innate dignity. After all, it’s sheer economics that forces most domestics to be domestics.” Bencab himself had proletarian roots, having grown up in Bambang—a working-class district of Manila—where his ties were still very strong.

That was the beginning of a whole series of noncommissioned portraits of Filipinos in the diaspora. (I was the subject for one. Titled Greencard Holder, it shows me standing in the Soho kitchen of my old cold-water flat, bathtub in the background.) Since then, Bencab has become fascinated with what he terms “very Filipino gestures” expressed in such emotions as gratitude and jealousy. He talked about how traditional Cordilleran art, especially its sculptural aspects, had influenced him. The figures inhabiting Bencab’s canvasses are indeed sculptural, exhibiting distinctly Cordilleran features—broad faces, rounded limbs and torsos, heavy feet.

By 1983, Bencab’s marriage to Caroline had turned rocky. That same year, Marcos’s most well-known political foe, Benigno Aquino Jr., was assassinated as he stepped off the plane returning him to Manila after a three-year exile in Boston—a murder that spelled the beginning of the end for the Marcoses. Bencab was in Spain when the news broke. He felt left out by history. “I asked myself, ‘What am I doing here?’ I was isolated.” In 1985, he and Caroline were formally divorced, and he flew back to the Philippines shortly thereafter. Instead of resettling in Manila, he chose Baguio, where a small but vibrant artists’ community had formed. “In my mind I wanted to be in Baguio. The cool weather. Good friends, my interest in holistic health, in the holistic approach. I wanted to be quiet. Of course, once you live here, it isn’t as quiet as you might think.”

Within a month, he had purchased property in Baguio, financing the purchase by selling off his collection of antique Philippine maps. In a period of two to three years, he had built his home, made up of two modest but well-designed buildings separated by a Japanese garden. The Baguio Artists Guild, which he helped to found, was at the forefront of the regional art movements in the country, and proving to be much more dynamic than the art scene in Manila, which is still very much enthralled by the Western model. In 1993, he chaired perhaps the guild’s most successful festival, which, for the first time, had invited foreign artists to participate. Its theme was Salubungan Agos, or Cross Currents. Painters, writers, performance artists, photographers, and critics, mostly from the Asia Pacific region, gathered in Baguio. Baguio’s small-city atmosphere fostered an informality that enhanced the exchange of perspectives, not the least of which were the enjoyable all-night sessions at Café by the Ruins, a popular, open-air café near City Hall. There, well-known Philippine writers such as Alfred Yuson, Ricardo de Ungria, and José Dalisay Jr., read from their works. There, too, amidst impromptu jam sessions by musicians in the café’s garden, discussions quickly became festive, boisterous—and fun. I had been a participant, collaborating with two friends, Los Angeles-based visual artist Yong Soon Min and her husband, the writer Allan deSouza, on an installation entitled Geographies of Desire that explored the intersections between colonial history and the way that that history continued to exploit, through mass merchandising, the former subjects of empire.

The art up in Baguio had a raw quality and, unlike in Manila, a spiritual element that acknowledged the rituals and the animist traditions of the Cordilleras. The Baguio artists had become the new shamans, opening up in directions previously looked down on as “folk art,” claiming the freedom to utilize Philippine icons, mythology, popular images, and native materials as well, from handmade paper to bamboo and woven mats. In the process, they were able to recontextualize themselves and the native self. Here, Bencab had found his niche, his home.

Unlike Bencab, Santiago Bose, another founding member of the guild, is from Baguio. This is where, after living abroad for several years, he grew up, and where he has returned. Santi, as his friends call him, is a Baguio artist of imagination and wit; once, he set up a bamboo mock-radar dish on a hill facing a real radar installation that had been put up by the U.S. military on another hill. We had become friends in Manhattan, where he had been living, but shortly after Aquino came to power in 1986, Bose (an only child) returned to Baguio in order to attend to his father, who had a history of high blood presure and was very ill. His mother passed away unexpectedly, before his father subsequently did, and an aunt quickly followed. Immediately his clan became suspicious. Perhaps someone, a mangkukulam, or sorcerer, had cast an evil spell on the family. In a city known for its healers, ranging from tribal herbolarios and shamans to psychic surgeons, it was easy to engage a warlock to find out who was behind this deadly mischief. Reading the signs, the warlock said the unlucky spell had been cast by a former girlfriend of one of Santi’s cousins. Cherchez la femme. Fortunately, no retribution was necessary, only a counter spell, to break the hex.

BAG artists were somewhat like that warlock, engaged in break-ing the Western hex. Keeping an eye out for a new Magellan, a great number of Filipino artists had ignored their indigenous traditions, and subsequently had a flawed sense of themselves as creators. With the founding of the guild, Santi now had another reason for staying. He had grown dissatisfied with working in New York where the art of countries like the Philippines had been routinely ignored. New York had numerous exhibition spaces, and Santi had had both group and solo shows in the early 1980s. But these were usually tagged as works by “minority” artists or by “people of color.” Such labels were deliberately misread by the cultural mavens with clout as implying tokenism rather than merit—a misreading that helped to justify their avoidance. It was a little different if you were a black artist or writer, where your work would be reacted to, noticed, or reviewed by the establishment, in part to assuage their collective guilt over the horrendous history of slavery and oppression. The art itself sometimes seemed secondary in these reviews, a perception that tainted even the most enthusiastic assessments.

As with so many Filipinos in the American diaspora, Santi felt that, as the ex-colonized, we were invisible. When acknowledged, which wasn’t often, we were seen as country cousins, asked, though politely, to remain in the kitchen, from where we could peek into the drawing- and living-rooms of the elite. If allowed in, it was only intermittently as transients or sojourners. Immensely complicating this process was the lack of historical awareness, and the often wilful ignorance of most Americans, of Westerners, about who we were and whence we came. (“The Philippines? Where is that?” “East of New Jersey.” “You speak English so well.” “I learned it on the plane coming over.”) Santi had had enough of that; he felt that creating a homegrown, largely self-taught aesthetic was crucial to moving away from what he termed an “overdependence on the West.”

Here in microcosm was the continuing, usually lopsided, dialectic between Third World assertions and First World dominance of resources and information. Here too was a dialectic between Baguio and Manila. Manila continued to be the breeding- and feeding-ground of artists whose mindset had been almost totally dominated by Western art history, and who produced work as though they were part of—rather than outside—that history. Their aesthetics, their works, were often emasculated to fit a so-called “international style,” which could then be placed on the global, i.e., Western, art market. Prettified eunuchs guarding the seraglio, they in effect reenforced, rather than deconstructed, the whole process of neocolonization. BAG would be an agent of decolonization, a raison d’etre that went hand in hand with the spirit of resistance that characterized the Cordilleras.

Switching to Tagalog, Santi states emphatically, “Kung Manila ang pipinta ng Igorot, iba. Kung Igorot ang pipinta sa Igorot, hindi ma-misrepresent.” (“When Manila portrays the Igorot, it’s different. When the Igorot portrays the Igorot, it’s accurate.”) The main issue was and would always be one of control. Bose’s efforts and those of Bencab and other fellow Baguio artists were related to the task of reclaiming both cultural and psychic territory from the invader, nowadays as likely to wear the glittery garb of pop culture as a military uniform.

In one of Bose’s installations, Pasyon at Rebolusyon, with its explicit reference to Reynaldo Ileto’s Pasyon and Revolution (a seminal work on nineteenth-century Filipino peasant aspirations for independence contextualized through sacred texts on Christ’s sufferings), indigenous materials, local iconography including a revolutionary flag, inscriptions, and miniature figures make up an ironic and highly eloquent altar. The piece continues his often irreverent attempts to articulate the nationalist feelings of those whom Carlos Bulosan, a Filipino poet and prose writer who had died of tuberculosis in Seattle in 1956, termed “the nameless in history.”

If the works of Bose exuded the ambiguities of a postcolonial sit-uation, so too did the works of two other guild founders, filmmaker Eric De Guia and installation artist Roberto Villanueva. De Guia’s 1977 Perfumed Nightmare, his first film, had been a hit in international film festivals from Berlin to Tokyo. A wry and quietly funny commentary on the neocolonial condition, the film was a sustained laugh at ourselves, at Catholicism, at our infatuation with Western technology—all the absurdities of a postcolonial hangover. The works of Villanueva, on the other hand, clearly reiterated the importance of nearly forgotten highland ritual and symbol. He used such forms as the village dapay (a circle of stone seats surrounding a hearth, where tribal elders would gather to discuss important matters) as well as ritualistic offerings to animist spirits, such as the launching of mini-boats on lakes, as reminders of a center the displaced Filipino needed to retreat to. Villanueva often placed himself at the vortex of his installations, performing as both artist and shaman. And indeed he succeeded in being both, his works at once timeless in their transcendental simplicity and elegantly modern. His last installation before he passed away from leukemia was a series of giant slim cylinders, each eight meters long, symbolizing acupuncture needles with which to help heal a wounded earth. Villanueva had an acute sense of how the pain inflicted over the centuries by both colonized and colonizer had seeped into the very ground they stood on.

The efforts of the Baguio artists to shape their own creative destinies touched an ancient nerve. Their works resonated with the viewers by reminding them that beneath official history lay another history—one that might have been shoved aside but that was nevertheless ineradicable. Still, the Baguio art movement was not about atavistic impulses. It was more of a reckoning, a reconfiguration, even reassessment, of the modern Filipino as she/he is situated: influenced (some would say, burdened) by a geography and a history that is like no other, and by the ambivalent baggage of a colonial past side by side

with modernist sensibilities and a tribal, communal self.

This collective of artists had embarked on rediscovering—and reinterpreting—home, one of the more rewarding if difficult voyages at the end of the millennium. But first they had to reclaim themselves from the anonymous stew into which history had flung them. This could be and often was a tedious process. In the works of the Baguio artists, however, the process metamorphosed into a voyage that doubled back onto itself: by moving back, it moved forward. A voyage, then, of delicious irony.