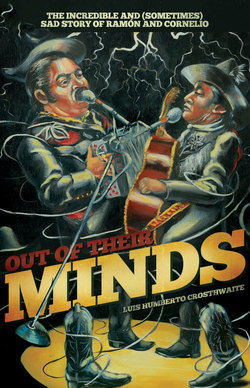

Читать книгу Out of Their Minds - Luis Humberto Crosthwaite - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMOMMY DEAREST

His mother was very straightforward. I don’t want you hanging out with that boy. What’s his name? He’s bad company. He can only drag you down roads of perdition and dishonor. I don’t have to remind you, my love, that your destiny is to fly above the mediocre. Maybe you don’t understand it now, but your mother offers you this advice because she knows that life is full of misfortune. It boils down to this: you should choose your friends wisely. I don’t want you to see him again, do you hear me? Enough of hanging out with those kind of people.

The son promised his mother that he would follow her advice to the letter of the law. He gave her a kiss on her left check and rubbed the nape of her neck, just like she liked it.

From then on rehearsal would be at his friend’s house.

You and the Clouds Drive Me Crazy

José Alfredo standing on a corner, dark sunglasses. He looks towards the clouds. Men, women, boys and girls come up to say hello, they want to slap him on the back, they want to chat with him.

José Alfredo is obliging: I owe it all to you, my fans. Your applause motivates me.

Thank you, he says to the people that gather around him. Thank you for your songs and your music, they respond.

He waves, smiles, gives hugs, hands out coins to the kids.

Several people ask him for autographs: Warm greetings for Hayde, Cordial thanks to Tico, Eternal gratitude for Denny, With affection for Blondie, To Gaby with care, Respectfully for Lilia.

A graceful signature for the dashing lawyer Pancho, another for the elegant Senator Felipe. An attentive flourish for the beloved Nena, for the gallant Armando, for the heroic Alfredo; inscription for the gentleman Poncho, Sandy the godmother and Andres the baseball player.

José Alfredo goes away.

People are happy for having found him: tired laborers, servants running to the market, bored professionals, enthusiastic bricklayers will have a better day, they all have an anecdote to tell: José Alfredo, José Alfredo. I saw him today, it was an accident. I was in the bar. I saw him pass by. He said hello to me. I talked to him. He liked my eyes. He is taller than I pictured. He’s shorter. He is very manly. He seems gay. He said to me. He talked to me. He was smiling.

José Alfredo goes away.

The bodies scatter, the mouths smile, the hands wave a goodbye, the feet continue their paths down the city sidewalks.

And only stories remain.

And the music.

The music that stays in the street for days.

Their First Gig

They made their debut at Aunt Yadira’s birthday party. The family was very kind and enthusiastically applauded their versions of “Wildwood Flower,” “Storms Are On the Ocean,” “The Long Black Veil.” Ramón and Cornelio promised to come back and play at their next party.

Later, Aunt Yadira came up, and in a maternal tone, explained to them that in reality they were very bad musicians and their arrangements were like massive train wrecks. Not just any train wrecks. No. Train wrecks with passengers. Nightmare, pain, irreversible tragedy.

“Why don’t you guys try another line of work?”

With great seriousness, they reflected on the suggestion of Aunt Yadira and were on the verge of abandoning music. Ramón could be an architect, his mother would like that, and Cornelio could make little plaster statues.

But something unexpected happened: one day Cornelio was walking down the street when he noticed a blue space was opening in the cloudy sky and from it emerged a delicate and brilliant light that reached down to his feet.

“Hey, what’s up? Come a little closer, I have something to tell you,” God said to him.

The First Cowboy Hat

Ramón has just bought a cowboy hat, his first hat. Perfect, superlative. It was there, in the store. First he tried on others, he didn’t want to inflate its ego. Some were too big on him, others too small. He didn’t want this perfect hat to feel that it was the only one in the world, he didn’t want to make it conceited and vain before its time. It’s like when you are attracted to a person but you don’t want to show it too soon so that it won’t be an easy thing; you know the affection is mutual, but the roundabout way is much more delicious than the straight line. So Ramón circled the other hats, flirted with them, as if he were going to ask them to dance, one after another, until that splendid Stetson was the only one left. Of course if it had been a person, it surely would have been irritated by the wait and would have refused to dance. But since it was a hat, it was more than willing. Ramón didn’t merely place the hat on his head, for him it was an act of coronation. He put it on and modeled it in front of the mirror.

Hat tilted slightly to the side.

Hat tilted forward, covering the eyes, giving mysterious airs.

Hat tilted back, giving the look of a horse’s mane.

Hat over his chest, held with two hands, in a sign of respect.

Hat lifted up a little, as if to say hello.

Ramón running with hat.

Ramón avoiding a punch without dislodging hat.

Removing his hat in salute while bowing to an appreciative audience.

It’s not easy to explain the relationship between a man and his hat. It is an object that is always going to be there, very close to the head. He sets it on a table and sits down. Watches how the light caresses it and how it projects an elegant shadow.

He hangs it from the back of a chair: position of the hat during a game of poker.

Hat down, arm straight, held by the left hand: position of the hat at church, during Mass.

Hat over the heart: position during a declaration of love.

Hat in the hand, fanning, one side to the other: function of the hat on a hot day.

Hat tossed with the right hand so that it flies through the air and lands perfectly on the hook of a coat rack.

Next purchase: a coat rack where he can hang his beloved hat.

Partners

Hey, what’s wrong? Come a little closer, I have something to tell you.

Hey you. I’m talking to you.

Don’t go.

I want to make a deal with you.

Come here, don’t be scared.

Do you know who’s talking to you?

Don’t be scared. Don’t be yellow.

You like music? Well, we’re going to talk about music, what do you think? I love music too. Not just any kind though. The kind that strikes deep into the heart, the kind that makes you cry and hurt and remember your buddies. The kind you hear on the radio and say: Hey, now that’s a song, I want to listen to it again and again and again. That’s music. Where are you going? You can’t avoid Me.

You can say no to Me, you can tell Me that you aren’t interested in going into business with Me. And I’ll go, it’s that easy. I’m not a creep. But first you have to hear Me.

Well, actually you don’t have to.

I don’t force anybody. I gave up on that already. Everybody can do their own thing.

But it’s a good deal for you.

Really.

Listen to Me.

It’s. A. Good. Idea.

It’s an indefinite contract. You can’t lose. Guaranteed success. We have to do it together. You can’t do it alone, I can’t either. Collaborators, partners. Are you in? You want to think it over? Well, think about it. But I don’t like to wait either. I’ve waited enough times. Think fast. If not, then that’s it for us, goodbye, it’s finished, and you lost the opportunity, I swear you lost it.

And forever.

I’m Looking Through You

His mind is blank, free of thoughts. Emptiness. Uninhabited space. Fathomless loneliness. A path, maybe.

You could describe it like this: a long road, a straight line, paved, in the desert. A formidable distance.

Suddenly, far away, a musical point appears. A faint sound that can barely be identified as sound. An incomprehensible melody, approaching. A little later, that melody acquires a definite form and some verses begin to blossom around it: the exact poem wrapped in the exact music, not one syllable too many, not one missing beat.

Cornelio opens his eyes and the song is right there, in front of him, waiting for him. He watches it for a long time, ecstatic. Finally, his fingers on the string of the bajo sexto help it spring forth:

“Your Beautiful Eyebrows”

Having just been born, the song feels trapped in the little house of its creator. It dreams of wide open spaces, where it can run, where it can feel free. As soon as Cornelio turns his back, the song escapes the house through the window. It feels the heat of the pavement, walks for the first time among the people of the border, slides between cars and passersby, climbs into trucks and taxis.

Every moment is a new experience.

The song wastes no time in learning to flirt and wiggle its hips with a sensual and captivating rhythm.

Men watch it pass by as if it were a beautiful woman and turn to check out her behind.

Women watch it pass by as if were a handsome man and turn to check out his behind.

Children understand that it is only a song, and they smile.