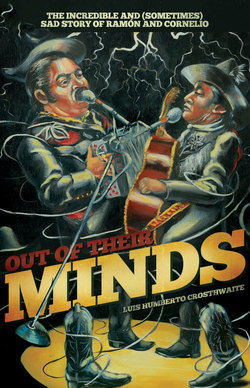

Читать книгу Out of Their Minds - Luis Humberto Crosthwaite - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMY BUCKET’S GOT A HOLE IN IT

During the day, the Strip doesn’t have a personality that sets it apart. It seems abandoned. It’s a street like any other street in a border city like any other border city. When the sun goes down, the Strip wakes up, puts on its best dress and does what it can with its makeup so nobody notices the wrinkles.

It dolls itself up with lights and bright colors, perfumes of tacos and food with too much lard. The drunks arrive on the Strip and look for the perfect place to sleep on its sidewalks. The doormen at the bars take out their stools to sit next to the doors and pass the night. The whores arrive, radiant and fresh, still smelling of talcum powder and without a single drop of sweat. The bottles and the glasses on the bars are clean and perfectly placed. The dance floors become anxious, like school girls, waiting for the happy dancing feet of not-yet-arrived couples to prance on their faces. Music swells from large speakers, musical instruments and jukeboxes. Hotel clerks check the rooms, and one or another might christen a room with the help of an affectionate chambermaid.

The citizens of Tijuana timidly enter the Strip, still without a drink to remind them that they are the kings of the night. One after another, the bars sprout from the earth. And the norteño musicians begin their eternal tour, offering songs that lift the spirit and make the heart beat to the rhythm of a Mexican two-step, a polka or a schottische.

On weekends there is no loneliness on the Strip, someone has managed to hide it away in a plastic bag, and it only returns to its owners when the sun comes up.

There’s a Tear in My Beer

Ramón and Cornelio arrived at the Inferno very early. They’re nervous because this is their first time to ask for work. They want to make a good impression.

“Are you guys musicians?” the owner asks.

“The Relámpagos de Agosto, at your service. Would you like to hear a song?”

“What for,” he answers. “It doesn’t matter whether I like your music, only that the bunch of vagrants who show up later like it. The job requires that you play something with a lot of feeling, something that makes the customers remember a lost love, maybe their momma that just died. The idea is for them to feel so much sorrow that they’ll want to keep drinking.”

Ramón and Cornelio understand that they have received their first lesson. The teacher continues: “And seeing as how you are here so early, why don’t you help me move these cases of beer?”

The Relámpagos move cases, sweep the floor and take chairs off the tables. The customers start to arrive at about nine.

“A song?”

“No.”

“Can we play you a song?”

“No.”

“A corrido, a bolero? What would you like?”

“No.”

“Something to dance to?”

“No.”

“‘Wildwood Flower,’ ‘Storms Are on the Ocean,’ ‘The Long Black Veil’?”

“No.”

“‘Pennies from Heaven,’ ‘What a Wonderful World,’ ‘Gentle Fatherland’?”

“No.”

“‘I Can’t Stop Loving You,’ ‘The Very Thought of You,’ ‘Death Without End’?”

“No.”

“‘Paper Moon,’ ‘Please Send Me Someone to Love,’ ‘The Red Wheelbarrow’?”

“No.”

“One of our own songs?”

“No.”

At three in the morning, closing time, they move boxes, put the chairs on the tables and sweep. Maybe tomorrow they will have better luck.

A HONKYTONK PARADE

The Inferno

Club Paradise

The Tap

The Cat’s Meow

The Chicken Coop

The Pine Knot Junior

The Prickly Pear

The Boiling Point

The Elbo Room

Friendly Atmosphere and Nonstop Music

Ramón and Cornelio walk the same streets as the other bands; they cruise the same restaurants and bars. They make friends with bartenders and waiters, with pimps and prostitutes. The first days of the week tend to be bad days, they can’t find customers. On those days the Strip, which is generally bucolic and festive, wraps itself in silence and its inhabitants walk into the streets for a breath of fresh air and to chat. The employees of hotels, bars and liquor stores sit on the sidewalks, telling sad stories about lost children and abandoned women. After a long time of listening to these stories, Ramón and Cornelio think of just the right song. They sing a nostalgic melody that is the perfect background music for the mood.

Waiters, bartenders, informants and pimps respect them. Even the other musicians. There’s always someone there to accompany them on the bass, the redova or the saxophone. Suddenly, another accordion pops up and accompanies the Relámpagos, and then another bajo sexto, and a few guitars. And there’s always a whore with a beautiful voice or a bartender that sings a good harmony. And the Strip, on sad days, fills itself with music and celebration. A friendly celebration. A celebration where sins and sorrows don’t exist.

“Wildwood Flower,” “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” “Jack of Diamonds,” “The Very Thought of You” become hymns of the night. And from then on, everybody can forget what needs to be forgotten and remember what needs to be kept close.

A Question of Feet

Ramón and Cornelio killing time, swatting flies, waiting for customers.

“…”

“It’s a question of feet.”

“What?”

“Women.”

“Women?”

“That’s what my Aunt Yadira told me.”

“When did you see your Aunt Yadira?”

“Not too long ago.”

“When?”

“Wednesday.”

“That can’t be; on Wednesday you were with me.”

“Then it was Thursday.”

“Thursday and Friday you were with me too.”

“Saturday?”

“Maybe it was Tuesday.”

“Yeah, it was Tuesday. Tuesday morning, when I went with my mom to the store.”

“It was Tuesday morning, man.”

“I didn’t want to go, but my mom insisted.”

“Tuesday morning my Aunt Yadira told me about the feet of women.”

“My mom is usually more independent. She doesn’t need me to go with her to the store.”

“This is why I don’t have a girlfriend.”

“I’m not sure what was up with her that time.”

“It’s a question of feet.”

“When my mother changes her routines it is always something that she plans—I know this about her.”

“I’m talking about women’s feet.”

“My mother’s feet, for example.”

“Those of women in general.”

“My mother doesn’t have pretty feet.”

“That’s what I’m telling you.”

“What?”

“There aren’t any women with pretty feet.”

“What?”

“Yeah? Let’s see: name one.”

“…”

“You see?”

“Fuensanta.”

“Fuensanta?”

“Fuensanta has pretty feet.”

“Which Fuensanta?”

“That other Ramón’s girlfriend, the guy that writes poetry.”

“That Fuensanta?”

“The one and the same.”

“She doesn’t have pretty feet.”

“Yes she does, pretty and brown, like I like them.”

“You? What do you know about feet?”

“I know what needs to be known: two per person, five toes on each, ten toenails total.”

“You don’t understand.”

“Ah, now I don’t understand.”

“If you understood, you wouldn’t say that Fuensanta’s feet are pretty.”

“Whatever.”

“Fuensanta’s feet are NOT pretty.”

“…”