Читать книгу My Father Died for This - Lukhanyo Calata - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter One

ОглавлениеStandoff with a Mad Hatter

ABIGAIL

I had been so busy at work that morning, it slipped my mind to check my cellphone after sending Lukhanyo a text message earlier. Although the students were on holiday, my workload as marketing and development manager at the law faculty of the University of Cape Town had not let up. ‘Vac’, at least for me, was a time to catch up and complete tasks I couldn’t get to during term.

Around lunchtime I could finally catch my breath, so I sat down and attended to messages on my phone. One of them was from Lukhanyo. It read: Hey Abs, take a look at this, and let me know what you think.

‘Today (27 June) marks 31 years since the murders of my father, Fort Calata, and his comrades Matthew Goniwe, Sparro Mkonto and Sicelo Mhlawuli.

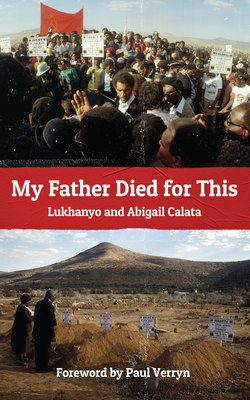

Known as the ‘Cradock Four’, their killings and funeral on 20 July 1985 became a turning point in the struggle for liberation with apartheid president PW Botha invoking a State of Emergency that was to last for years.

I made the decision to become a journalist after years of watching journalists coming to our home as part of their drive to tell the story of my father and his comrades.

Thirty-one years later, I now work as a news reporter, with the sole purpose of telling stories of my people with dedication, truth, and freedom. A freedom that many like my father either died or were imprisoned for.

It is therefore with great sadness that I am confronted with the disturbing direction being taken by my employer. A direction I believe flies in the face of what many have sacrificed.

The decisions [one of which was to ban the broadcast of violent service delivery protest] taken recently by the SABC [South African Broadcasting Corporation] cannot be described in any other way but them curbing media freedom. A freedom to report ethically, truthfully, and without bias.

As I reflect on this day and remember the occasions when leaders of our liberation movements stood at my father’s grave and waxed lyrical about the freedom he died for, I wonder where they are today.

How do they live with themselves? How do they watch as the rights and freedoms the ‘Cradock Four’ were brutally murdered for are systematically being undone?

Did I live without a father so that 31 years later, my own freedom and that of my colleagues are restricted within an institution that is meant to lead in media freedom?

What do I say to the son I have today about what his grandfather and my great-grandfather James Arthur Calata fought for?

I do not do this publicly to condemn my employers, but rather seek to remind some of them and all of us that we cannot forget that people like my father and many others died for us to have the right to speak truth to power when necessary.

They died so that we can in 2016 do what is expected of us, which is to lead where they left off: To serve this nation with pride, truth, dedication and ethics.

Aluta,

Lukhanyo Calata’

Gosh, Lukhanyo, this was heavy reading for a Monday. I immediately started thinking of the implications the release of such a statement would have for our young family. The week before, Lukhanyo had been interviewed for a vacant television assignments editor’s post at the SABC’s Sea Point office. It would be a step up for him, and by extension our family, were he to be the successful candidate. At the time of writing the statement, he was a television reporter for the SABC in its parliamentary office. He thought the interview the week before had gone well, but with interviews you can never be sure. I responded to his message, asking him not to go public with this statement, as he could kiss his chances of getting the assignments editor’s job goodbye if he went public with it. Little did I know that by the time I’d read his statement, my husband had already released it and that it had gone viral.

LUKHANYO

I was on leave at the time. That Monday morning, Abigail was at work and our three-year-old son, Kwezi, at school. After my morning devotions, I picked up my phone to check for messages and scan Twitter for the latest news. I found that Abigail and my good friend Koketso Sachane had sent me text messages about Jimi Matthews’s resignation. In June 2016, Jimi was acting group CEO of the SABC. I read his resignation letter, which he had posted on Twitter. To my horror, Jimi claimed to have compromised values he held dear ‘under the mistaken belief that [he] could be more effective inside the SABC than outside’. He blamed the ‘prevailing, corrosive atmosphere’ at the SABC for negatively affecting his moral judgement and making him complicit in decisions he wasn’t proud of. He ended the letter with, ‘What is happening at the SABC is wrong and I can no longer be part of it.’

This was a complete surprise to me and I’m sure to many of us in the various SABC newsrooms. About a week prior to his resignation, Jimi had filed an affidavit at the Western Cape High Court in which he’d sung the praises of Hlaudi Motsoeneng, the SABC’s chief destroyer, disguised as its Chief Operating Officer. In his affidavit Jimi had written, ‘his presence at the SABC is vital to the public broadcaster and that the SABC would effectively suffer without Motsoeneng’s leadership’.

The sentiment expressed in his resignation letter, however, was far removed from that in his affidavit. What could’ve happened in the space of a week that would so drastically change his opinion of Motsoeneng?

We (most SABC staffers) had known for a long time that something was amiss at the SABC, but to see Jimi finally stating it in black and white like this left me stunned. I read the resignation letter over and over, trying desperately to make sense of it all. I had always looked up to Jimi and had to some extent believed that as long as he was there, the SABC newsroom was a protected and sacred space. Now that he was gone, and having admitted so publicly that something was wrong at the SABC, I started to worry about those of us who would remain in the trenches, so to speak.

Just then, Koketso called. He was out of the country at the time, visiting his wife, Shanti, in Oslo, Norway. Usually our telephone calls start off with banter, jokes, and just plain nonsense. But this call was different. There was no banter, no jokes, none of the usual nonsense chit-chat. It was a very serious phone call, both in tone and content, right from the start. We had been good friends for around fourteen years at the time, and he was well aware of the significance of the date to me and my family. I was touched by his phone call, particularly as it was meant to commemorate this day with me. We then got to discussing Jimi’s resignation letter and what it meant for the already embattled public broadcaster and its Mad Hatter COO. I told Koketso how disappointed I was by Jimi’s decision, and that what perturbed me most was his frank admission ‘that what is happening at the SABC is wrong’. I was angry that Jimi, at least in my opinion, had thrown in the towel and allowed Motsoeneng to get the better of him.

I just couldn’t fathom how he and many others, including (at least) two non-executive boards of directors appointed by parliament, could allow this guy, a high-school dropout, to run roughshod over them like that. While I was in the middle of this rant, Koketso asked me what I was going to do about it. Something about his question struck a nerve in me. I mean, what could I do about it? It jolted me out of bed. I was now on my feet, pacing up and down the short passage in my home, the question hanging over me. About a minute passed and I still hadn’t – or rather couldn’t – answer the question. My emotions were in turmoil. I was angry; I was disappointed; I was fearful, yet I knew I had to do – or, at the very least, say – something publicly about what was going on at the SABC.

‘Why don’t you issue a statement?’ Koketso asked. I liked this idea, particularly as I could link it to my family’s commemoration of the 31st anniversary of my father’s disappearance and murder. It was rather fortuitous – at least for me – that Jimi had chosen this day to resign. I agreed we should draft a statement.

I wanted the statement to be strong, critical of the current state of and issues affecting the broadcaster, but I did not want it to get me fired. Suspended maybe, but not fired. Once I was happy with the statement after a few drafts back and forth between us, I had to decide what to do with it. I asked Koketso to send a copy to our friend and former colleague Gasant Abarder, who at the time was editor of the Cape Argus, one of the most widely read daily newspapers in Cape Town.

I sent a copy of the statement to Andisiwe Makinana, the parliamentary correspondent of City Press, a national newspaper. At the time, Andisiwe boasted just over 33 000 Twitter followers. I knew that with just one tweet from her, the statement would reach a critical mass of people in an instant. Barely a few minutes after I sent Andisiwe the statement, she called. Her voice was cracking, as if she had been crying. She told me the statement had brought her to tears. I’ve known Andisiwe for several years. We started working as journalists at around the same time and I had grown quite fond of her over the years. I never really thought a statement – particularly one I had written – could bring her to tears. She was even kind enough to warn me that the SABC, and Hlaudi Motsoeneng in particular, would not take kindly to my statement and that I should prepare myself. ‘They will surely come for you,’ she said. I was touched by her genuine concern for me and my family. The only problem, though, was that by then I had already taken the decision to go public with the statement. I honestly couldn’t care any more who or what would come at me in response. I had done what I needed to. Now it was up to them to do what they needed to do.

ABIGAIL

I expected Lukhanyo to be at home that Monday afternoon. So, after reading the statement, I called him hoping to chat to him about it. To my surprise, I found out that not only had he released the statement without my input, but he and our son, Kwezi, were by then on their way to the Cape Town offices of Independent Media. Upon reading the statement, Gasant (the editor of the Cape Argus), immediately asked Lukhanyo to come in for an interview. While I was speaking to Lukhanyo on the phone, the repercussions of what was happening slowly dawned on me. How could he go public with something like this without discussing it with me, his wife, first? How could he make a potentially life-changing decision without my input? I was getting worked up – an untenable state for me to be in at that point since I was still at work. In order to calm myself down, I asked after Kwezi and his well-being. But before ending our telephone conversation, I let my husband know in no uncertain terms that I was terribly upset by his decision to issue the statement without my knowledge or input and that we would discuss this when I got home later that day.

After hanging up, I went onto social media. I wasn’t surprised by what I found. The interest in and reactions to the statement on Twitter, Facebook, and news websites told me that what Lukhanyo had done resonated with people. I realised I could do nothing to stop it and that I, like the rest of the country, could only sit back and watch as things unfolded.

Unable to focus on work any more, I spent the rest of the afternoon staying on top of everything that had to do with the statement on Twitter and Facebook. The Cape Argus posted video excerpts of its interview with Lukhanyo on its platforms to whet readers’ appetites for the story that would become their front page lead the next day, 28 June 2016.

As I watched the short video clips and listened to my husband speak, I felt a sense of peace envelop me. It replaced my anxiety about what could or would follow the statement, yet somehow I just couldn’t reconcile myself to the fact that my husband had excluded me from the decision-making process when the consequences would directly affect the three of us – him, Kwezi, and me.

They were not home yet when I arrived there. The minute Lukhanyo walked through the door, with our excited son in tow, we started the promised discussion about the release of the statement. With Kwezi safely out of earshot in the bath, I told Lukhanyo that I did not appreciate his decision to issue the statement without my knowledge. I stressed that my problem was not with the content of the statement, but with the fact that I was completely excluded from the decision to release it when I, together with Kwezi, would be directly affected by its release. A heated discussion ensued. But Lukhanyo eventually realised his mistake and we agreed that going forward any and all decisions – particularly ones with such massive implications for our family – had to be discussed with me beforehand.

It was at this point that Lukhanyo informed me he had already accepted an invitation for an in-studio interview with eNCA, the SABC’s rival news broadcaster, for later that evening. I did not object to his doing the interview and, having had my say – impressing upon him the fact that he no longer had the luxury of making decisions on his own – I took up my rightful place as my husband’s main supporter (and cheerleader) in what in hindsight was the most pivotal moment of our lives together so far.

The next day, Lukhanyo and Kwezi graced the front page of the Cape Argus. Admittedly, I was extremely proud of my two boys.

LUKHANYO

Jimi Matthews was a veteran broadcast journalist, who had cut his teeth as a news cameraman and reporter, and was particularly active in the turbulent Eighties – probably the worst of the apartheid years. He was a role model to me – at least until the point of his resignation from the SABC. I felt Jimi should have expressed what he wrote in his resignation letter while he was still employed by the SABC. In my interview with Gasant and his deputy editor, Lance Witten, I recall saying, ‘Jimi’s resignation had hurt me personally because my father died for the freedom enjoyed by so many in South Africa today.’ I felt he had made a mockery of the sacrifices of my family, of his own family, and those of countless other families who had fought and lost their loved ones for us to get to this point as a nation. I told them, ‘I had to speak up while I was still at the SABC.’ I could and would not wait until my resignation before I spoke out about the dastardly decisions the SABC management were busy taking.

My statement had voiced a deep sense of frustration and despair, which, I realised later, was shared by many South Africans with regard to the prevailing situation in the country. What was happening at the SABC reflected what was happening at many – if not all – state-owned entities. Almost everyone my family and I met and spoke to in the days and weeks following the publishing of the statement was relieved, with many celebrating the fact that someone had finally had the guts to speak out against the daft decisions of the SABC’s management. I had fired the first salvo, they said.

Abigail also made me realise that, despite my being just 34 years old at the time, the public had responded to what she called ‘an inherent moral authority’ I possessed. She believed it stemmed not only from the legacy of activism left by my father but also that of my great-grandfather, Canon James Arthur Calata, a prominent black leader in the Anglican Church in the Eastern Cape. More significantly, though, my great-grandfather had served both as president of the Cape ANC as well as the movement’s national secretary-general from 1936–1949. His years in that office remain among the longest for any secretary-general in the 106-year history of this liberation movement.

ABIGAIL

South Africans had responded with overwhelming positivity to Lukhanyo’s statement, and soon my husband was no longer mine. Kwezi and I now had to share him with the rest of the country. Everyone wanted a piece of him in those first few days following the release of the statement. Practically every news outlet called, requesting interviews. We were happy to share him, though – particularly as I now believed with every fibre of my being that he was doing the right thing and that, whatever the outcome, we, as a family, would be all right.

We didn’t have to wait long for the SABC to respond. Just four days after the release of the statement, Lukhanyo was charged with breaching the SABC’s code of conduct. His charge sheet read:

‘Re: DISCIPLINARY HEARING

You are herewith notified to attend a disciplinary hearing to be held of Friday, 1 July 2016 at 09:00 in ASD Boardroom, Room 2442 of the Radio Park Building of the SABC Offices in Johannesburg, in order to investigate the following alleged offenses brought against you:

CHARGE 1

NON-COMPLIANCE WITH THE DUTIES OF YOUR CONTRACT OF EMPLOYMENT

alternatively

CONTRAVENTION OF SABC RULES & REGULATIONS

In that

You in your capacity as a Reporter, for Parliament Television News in Cape Town, allegedly liaised with the media i.e Cape Argus (28 June 2016), Star (28 June 2016), Sowetan (28 June 2016), eNCA (Interviews conducted on 27 & 28 June 2016) and Radio 702 (interviews conducted on 27 & 28 June 2016) without having had permission to do so.

In doing so it is alleged that you contravened Regulation 2 (d) of the SABC’s Personnel Regulations i.e.

“An employee:

(d) Shall not without prior written consent of the Group Chief Executive, make any comments in the media …”

Should these facts be proven it will constitute an act of non-compliance with the duties of your contract of employment on your part alternatively contravening SABC rules and regulations.’

This was the official charge. The unofficial charge, as we all knew, was that Lukhanyo had dared to speak out against the despotic rule of the SABC’s COO, Hlaudi Motsoeneng. This is the same man whom the Western Cape High Court would later find to be ‘unqualified to hold any position at the public broadcaster’.

Lukhanyo’s charge sheet was sent to his work email address, which he could not access from home. He only became aware of the charges against him the following week when he returned from leave.

So, instead of appearing before a disciplinary panel on Friday, 1 July 2016, Lukhanyo, Kwezi, and I spent the morning protesting outside the SABC’s offices in Sea Point. We were asked to be part of a picket organised by the Cape Town advocacy group, Right2Know Campaign. We wanted to voice our dissatisfaction with the SABC’s decision to ban the broadcast of violent service delivery protests. In criticising this directive, Lukhanyo – inadvertently and unbeknown to him at the time – had joined six of his Johannesburg colleagues who had also opposed this directive.

Three of them, Thandeka Gqubule, Foeta Krige, and Suna Venter, were by then already suspended. They had raised their objections in a line-talk discussion about the directive not to cover a protest by the Right2Know Campaign right on the SABC’s doorstep in Auckland Park, Johannesburg. Line-talk meetings are for editors and producers to discuss how to cover the top stories of the day. Three other SABC employees, Jacques Steenkamp, Krivani Pillay, and Busisiwe Ntuli, would under normal circumstances not have done anything wrong when they sent a letter to news managers requesting a meeting with them to clarify some of Motsoeneng’s pronouncements. Under the abnormal circumstances prevailing at the SABC at the time, however, this innocent letter had become an offence punishable by dismissal. Another SABC employee, Vuyo Mvoko, took a page from Lukhanyo’s script and went on to write a scathing letter, titled ‘My Hell at SABC’, which The Star and its sister publications carried on their front pages on 6 July 2016. Thandeka, Suna, Busisiwe, Krivani, Jacques, Vuyo, Foeta, and Lukhanyo – or ‘the rebels’, as Lukhanyo often refers to them – became known as the SABC 8.

On 8 July 2016, Lukhanyo and his colleagues were informed of more charges levelled against them by their employer. This time, notices in terms of Schedule 8 of the Labour Relations Act were issued.

Sections of their charge sheets read as follows:

‘You are hereby notified in terms of Schedule 8 of the Labour Relations Act no 66 of 1995 that allegations have been received that you are continuing to commit further acts of misconduct after receiving your letter informing you of your disciplinary hearing in the following respects:

On Sunday, 3 July 2016 you caused an article to be published in the Sunday World newspaper thereby criticising and displaying disrespect and persistence in your refusal to comply with an instruction pertaining to the editorial policy of the SABC as well as the directive not to broadcast visuals/audio of the destruction of property during protest actions.’

The letters end with:

‘It undermines the editorial responsibility and authority of the SABC as vested upon its Chief Operating Officer in terms of paragraph 2 of the SABC Revised Editorial Policies, 2016.’

Outside of the SABC, the eight enjoyed great support from the public and their peers. On 9 July 2016, they were recognised by the South African National Editors’ Forum (SANEF), which awarded all eight of them the 2016 Nat Nakasa1 Award for ‘media practitioner[s] who [have] shown integrity, commitment, and courage’ in the course of their work. The public support would increase seven-fold a few weeks later when the SABC decided to summarily dismiss all eight of them.

LUKHANYO

18 July 2016 was a Monday. I’d been back from leave for two weeks and, besides an updated charge sheet, things were quite normal for me at the office until around six that evening. Krivani Pillay sent a message to our WhatsApp group urging us to check our emails urgently. She seemed in a bit of a panic. She had just received an email from management informing her of her dismissal. Within minutes of one another, Suna Venter, Jacques Steenkamp, and Foeta Krige all confirmed the worst possible news – they too had been dismissed.

I checked, double-checked, and then triple-checked my emails. Nothing, no email. I was safe for now, I thought, at least until my disciplinary hearing which was arranged for 29 July 2016. Surely the SABC wouldn’t touch me until then.

Shortly after I got to the office the next morning the parliamentary editor, Vuyani Green, came into the newsroom to inform me that I should stay in the office, as there were managers from the SABC’s Sea Point offices coming to see me. I knew then that I too would be dismissed.

The feeling of impending doom is one I would not wish on my worst enemy. For the first time during this entire ordeal, I was afraid. I couldn’t stop thinking about my wife and son, and how I had let them down. The fear of losing all I had worked for in the five years while I had been at the SABC left me stunned for a few minutes. I tried to keep busy and not think about the meeting, but my eye kept catching the clock. Two hours of waiting eventually passed. The moment finally arrived when Vuyani returned to call me into his office. There, I found Western Cape human resources manager, Shouneez Moosajee, and a gentleman who introduced himself as James Shikwambana, then acting provincial general manager.

Shikwambana curtly informed me that he had been sent to deliver a letter to me, and to inform me officially that the SABC was terminating my contract. I looked at the big brown envelope he slid casually across the table and asked him how the SABC could dismiss me without having heard my side of the story. My question caught the HR manager off-guard. Obviously startled by this revelation, Shouneez asked if there had been no hearing at all, to which I replied no.

With nothing left to be said, I picked up the envelope, thanked Shikwambana and Shouneez, and excused myself. Vuyani walked me out of his office and kindly offered me his apology for the manner in which the SABC had handled my dismissal. By this time, my emotions were all over the place. In the corridor, just outside his office, I opened the envelope and read the one-page letter:

‘Dear Mr Calata,

NOTICE OF TERMINATION OF EMPLOYMENT

I refer to the notice in terms of Schedule 8 of Labour Relations Act served on you on 8 July 2016. Further, I confirm receipt of a letter from your union, Bemawu, dated 11 July 2016. It is [the] SABC’s considered view that the said letter from your union does not amount to [an] adequate response to the issues/concerns raised by the SABC against you.

It is common cause that you have made it known to the SABC that you will continue to disrespect the SABC, your employer. It has now become clear to the SABC that you have no intention to refrain from your conduct of undermining the SABC and the authority of its management. In the premise [sic] your continued acts of misconduct have become intolerable. Your employment with the SABC is thus terminated with immediate effect, being 18 July 2016. You have a right to refer a dispute at the CCMA in the event that you are not satisfied with this decision.’

I was scared, angry, disillusioned – and now officially fired. At that moment, the safest place I could think of was the office of my assignments editor, Isabelle de Taillefer. I had always enjoyed a good working relationship with her. There was a strong Cradock connection between us. She, a priest’s daughter, had spent part of her childhood there, before her family relocated to Bedford, a town around 90 km from Cradock. Isabelle was also the same age as my mother, so even though she was an immediate line manager, she was also very much a maternal figure to me in the office. And as mothers so often do, she must’ve seen what I felt on my face because she jumped up from behind her desk, arms wide open, the moment I walked into her office with my brown envelope in hand. I could barely finish telling her that the SABC had fired me before she wrapped her arms around me and allowed me to cry on her shoulders, right there in her office.

After a few minutes, I was ready to face the rest of my colleagues again, who by now were aware that something had happened. So, with brown envelope in hand, I braved the newsroom as I made my way towards my desk. Once there, I took a picture of my letter of dismissal and posted it to our WhatsApp group. One of the guys in the group must have tweeted it. I had barely sent it when my phone began to ring incessantly and messages of support began streaming in. I was the last of the eight to be fired that Tuesday morning.

ABIGAIL

Ironically, 19 July is a day before yet another important date in my husband’s life. On 20 July 1985, his father, Fort Calata, was buried in one of the biggest funerals in apartheid South Africa, alongside his friends and comrades Matthew Goniwe, Sparro Mkonto, and Sicelo Mhlawuli.

On that cold Saturday afternoon in Cradock, an estimated 60 000 mourners not only defied a government ban to travel there, but they made the funeral one of the biggest political rallies of the time. It was a true turning point in black South Africans’ struggle against oppression and injustice. The funeral of the Cradock Four was a powerful political statement, one which the government of PW Botha could not just ignore.

With Lukhanyo now dismissed and my fears for our family realised, I felt we had to regroup. Our lives had been turned upside down in a matter of days and we hardly had a chance to catch our collective breath. My birthday was coming up in just a few days, on 22 July, which I thought would be the perfect opportunity to unwind, spend some quality time together as a family, and forget about our ordeals of the preceding weeks – if only for that day. In the few days leading up to and following his dismissal, Lukhanyo was busier than ever. There were meetings with his union, with lawyers, with former colleagues, and meetings with sympathisers from both civil and faith-based organisations. And the media requests for interviews had not let up. I suspect Lukhanyo’s personal relationships with most of the journalists who approached him for interviews made it difficult for him to say no to them.

In one of those interviews, Carla Bernardo from the African News Agency wanted to know whether Lukhanyo would fight his dismissal. His nonchalant response was, ‘Yes, of course, I come from a family of fighters.’ This simple statement would again make the front pages of a number of newspapers the next day. By now, Lukhanyo and his seven colleagues had received various offers from lawyers prepared to argue their cases in the Labour Court as they sought their immediate reinstatement.

During this dizzying time, I got to witness a different side to my husband – a side I had not known existed until then. I saw how he was buoyed by and relished the battle with the SABC. Most importantly, though, I witnessed how effortlessly he had taken to activism. In one meeting, he managed to convince a group of pastors representing some 24 churches to issue a statement calling on then Minister of Communications, Faith Muthambi, to intervene immediately in the SABC matter and reinstate the SABC 8. He later casually told me that it had taken him less than an hour to get them to agree to this.

My birthday, however, would not work out as I had planned or wanted. Just two days before, Lukhanyo received a call from the office of the ANC’s deputy secretary-general (DSG), Jessie Duarte. She requested a meeting, which meant he would have to travel to Luthuli House, the ANC head office in Johannesburg. So instead of a nice, quiet day at home with my husband and son, I ended up taking Lukhanyo to the airport early that Friday morning for his flight to Johannesburg.

Lukhanyo was now the latest Calata called up to ANC headquarters to brief its office bearers on a matter of national importance – much like his father once did and his great-grandfather before him. The historical significance of this fact was not lost on me and neither, it seems, was it lost on his mother, Nomonde. Although based in Cradock, she met him at the airport in Johannesburg and accompanied him to the meeting with Duarte.

LUKHANYO

I am always a ball of nervous energy just before boarding a flight. Strange thing is I don’t really know why. These nerves are there every time, despite my job as a journalist, which requires that I travel by airplane quite regularly. This flight to Johannesburg would prove no different. Added to this, I felt terrible for leaving Abigail, who had taken ill with the flu, with Kwezi on her birthday to attend a meeting with Jessie Duarte. I had decided earlier that week that I wouldn’t rack my brain trying to figure out why the ANC’s DSG had called me to a meeting. This, however, was easier said than done. Until this point, my association with the DSG had been limited to purely professional engagements, mostly at press conferences either in Cape Town or Johannesburg. From those few encounters, I knew she was a no-nonsense kind of lady.

Fortunately, the flight to Johannesburg that Friday morning went by quite smoothly. We landed at OR Tambo International Airport ahead of schedule. It was a crisp mid-winter’s morning in the city, which felt a lot colder than Cape Town. Despite the nip in the air, I chose to wait for my mother and elder sister, Dorothy, outside the terminal buildings at the airport. It had been a while since I had last seen them. My mother still lived in Cradock, although lately she seemed to be spending most of her time travelling between Cape Town, where I live with my family, and Limpopo, where Dorothy lived with her family. It was her desire to see and be with her grandchildren that had her traversing the country almost every other week. Anyway, after a brief wait at the airport, the two arrived to pick me up. The hugs and hellos were longer than usual from both of them. It made me realise then that they hadn’t seen me since the statement had hit the headlines and, although they’d called almost every day, this was the first time I was physically in their presence. No amount of phone calls could ever make up for that. We set off for Luthuli House, with me in the back seat. In those few moments, as we drove from the airport, I felt completely unburdened. For the first time in weeks, I could just breathe, relax, and take it easy. I felt so reassured being with them, and I knew that despite all the drama of the last few weeks, my family and I would survive this.

I could gather my thoughts and listen to Dorothy regale me with messages of love from my niece – also called Lukhanyo – and two nephews, Phumudzo and Junior. These two women in the car with me had taken care of me most of my life and here they were once again making sure that I was okay. I felt safe and deeply loved.

As we approached the Johannesburg CBD, inching ever closer to 54 Pixley Seme Street, I could sense the mood in the car change. We all grew quiet, until my mom snapped us back to the reality of why the three of us were reunited in Johannesburg. She mentioned how my ordeal had stirred in her a deep-rooted fear for my safety and well-being. In the same breath, she was outraged by the situation I found myself in. It was a very difficult time for her, more so than anyone in the family could have suspected. You see, my mother had over the years done almost everything she could to keep me as far removed from active politics as possible. She feared my involvement in politics or activism of any sort would more than likely result in my being killed just like my father. Yet, despite her desperate attempts, particularly as I got older, here I was, her only son, summoned to Luthuli House and her worst fears seemed realised. She had been on this emotional rollercoaster with my father before. She didn’t like it then and she despised it even more now.

My mother was particularly scathing of the circumstances around my dismissal. According to her, the manner in which the SABC had fired me was far too similar to the circumstances surrounding my father’s dismissal from his post as a secondary-school teacher, in the months leading up to his assassination. This SABC saga had been a terrible case of déjà vu for her. I could only apologise to her for my part and – although I think unconvincingly – tried to assure her that it had not been my intention at all for things to turn out the way they did.

Upon our arrival at Luthuli House, the security guard at the entrance to the parking lot said he had been informed to expect us, and directed us to where we should park. I’d been to Luthuli House once before for a press conference ahead of the 2009 national elections; this visit, however, was very different. Both my mother and sister were familiar with the building. My mom had visited Luthuli House several times before too, particularly during the period when Kgalema Motlanthe served as the movement’s secretary-general. She had sought assistance from his office for the education of Dorothy, Tumani, my younger sister, and me.

We entered the building through the glass door nearest the parking lot. I informed the courteous lady at reception that we were there to see Jessie Duarte. ‘The DSG?’ she asked. I nodded. ‘Sixth floor,’ she said.

A gentleman named Lungi Mtshali was waiting for us on the sixth floor. He was the one I had liaised with to make arrangements for this meeting. As we walked towards his office from the elevator, I remember looking around, trying to take it all in. I was after all walking the corridors of the headquarters of the ANC, the liberation movement to which my family had such a deep-rooted connection. My family’s history is inextricably interwoven with that of this movement. I had never given much thought to what the offices at Luthuli House looked like, but once I saw them, I was pleasantly surprised. I wasn’t sure what to make of the gold-flaked wallpaper, but I thought the offices themselves were quite modern. They were well lit with spacious corridors, and rather busy despite it being a Friday afternoon.

Lungi was waiting for us outside his office about halfway down the corridor. He was a softly spoken guy with a beautiful smile. After the formal introductions, he informed us – much to my mother and sister’s chagrin – that I would meet with the DSG alone at first before the two of them could join us. I was fine with this. It was after all the reason why I had come, but my mother wasn’t pleased with this arrangement. Lungi tried desperately to assure her that she and Dorothy would join us in the meeting, but only after I had met one-on-one with Duarte. My mom’s vehement protestations against this arrangement, unfortunately, came to nothing.

Up to that point, I had not allowed myself to think about this moment – what it all represented for me on a personal level, for my family, or indeed my father. Lungi then asked me to follow him. I glanced at my mom, who was close to tears. I told her I’d be fine, but I don’t think she heard me and, if she did, she definitely didn’t believe me. Lungi and I made our way through his neatly kept office. As I walked just a few paces behind him, I had a revelation of the significance of this meeting and my presence at Luthuli House. Despite the magnitude of the moment, I tried desperately to keep calm. I needed to be composed when I met Jessie Duarte.

I loved the amount of natural light shining into her office. The large windows seemed to make the office bigger than it actually is. It was warm too, spaciously laid out with very little pretence in the decor. It’s a political office, I suppose. Duarte sat behind her desk, about to finish reading a document which I imagined to be a report of some kind. I’d seen her many times before in press conferences, and I’d always found her very stern and strict. Yet, as she took off her glasses and walked across her office to greet me, she had such a warm and friendly smile, which I, of course and very naturally, reciprocated. I remember being amazed by the fact that she wore takkies to work. I liked that about her. She immediately put me at ease. She’s harmless, I remember thinking – a thought I took back almost immediately when she gave me quite a firm handshake, before inviting me to sit down at a meeting table. There was a genuine exchange of pleasantries and the obligatory question about the flight to Johannesburg. With that out of the way, we got down to the business that necessitated our meeting.

She began by apologising for the situation that my colleagues and I found ourselves in, and explained that she had wanted to meet with me to get my side of the sorry SABC saga. Telling me she found newspaper reports about what was unfolding at the public broadcaster quite contradictory, she said she needed a first-hand account of what was actually going on at the SABC. She added that our chat would help her put together a report to the officials for a meeting taking place the following Monday. My plan, or what little of it I had, was to make the most of the opportunity this meeting provided. I didn’t know if I would ever get the chance to speak to an actual decision-maker again, so I began to tell her my story from the very beginning.

For me, it had all started on the evening of 13 February 2014, the night of the State of the Nation Address. This was the last State of the Nation Address before the general elections in May that year. By then, I had been in the SABC’s employ for three years. Prior to that night, I had not come across anything out of the ordinary for a journalist working in any other newsroom. But around ten o’clock that evening, an encounter I had with Jimi Matthews, who was then head of news, changed everything. It was just outside the entrance to the Marks Building in the parliamentary precinct where I had my first-ever instruction to censor the news at the SABC. I demonstrated to Duarte how Jimi had grabbed me by the scruff of my jacket and instructed me not to get him into shit and that I had to go and cut him positive soundbites of reactions from opposition parties following the president’s address.

My dilemma with this instruction was two-fold. Firstly, there were the obvious censorship issues; and, secondly, there were no positive soundbites to cut. 2014 was an election year. Politicians, particularly those from opposition parties, are shrewd enough to understand the value of those few minutes that we interview them live on air. They know that what they say is broadcast live to the nation, therefore none of them – particularly in an election year – would use those precious minutes to sing the then president Jacob Zuma’s praises. So, without fail, not one of them had anything remotely positive to say about the president’s address.

I told Duarte how my interaction with Jimi that night had troubled me, not only as a journalist working in a free and democratic South Africa, but also as the son of Fort Calata. It had upset me deeply that I had been asked to do something that had such strong ties to apartheid South Africa. In the apartheid years, particularly in the turbulent Eighties, the SABC was truly ‘his master’s voice’, a tool used to great effect by the brutal and murderous regime of PW Botha. How could Jimi of all people dare to ask me to do to my people the exact same things successive apartheid governments had done to them before? It was something I was not prepared to do.

Today, I look back at that moment with Jimi and feel so proud of my defiance, particularly for not betraying the dreams and aspirations of all South Africans. I should add that I never did cut those soundbites or any soundbites for that matter. Instead, I relayed Jimi’s instructions to the parliamentary editor, Vuyani Green. He too must have felt uneasy at these instructions, because he asked me to pass the message on to my colleague Bulelani Phillip, who was working on the reactions piece for the next morning. I refused to do that too.

I then grabbed my jacket, bag, car keys, and bid everyone a good night. I recounted other subsequent incidents to Duarte – such as the time I received the instruction that we (TV reporters in parliament) were no longer allowed to use an iconic and historically significant reel of footage, where members of parliament representing the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) disrupted a sitting of the National Assembly. Chanting ‘Pay back the money!’, they would not allow Zuma to address the National Assembly, saying he first needed to pay back several millions of rand, as per the findings and recommendations of then-Public Protector Thuli Madonsela.

In her report, titled ‘Secure in Comfort’, Madonsela had found that public money indeed was used illegally to build non-security-related structures, including a kraal, chicken-run, amphitheatre, and swimming pool at Zuma’s private home in Nkandla, KwaZulu-Natal.

To this day, I have no idea who in the SABC had issued the directive that the EFF footage be banned. I remember, though, that I flatly ignored the instruction and continued using the footage to overlay my piece, which looked back at the key moments of the 2014 parliamentary year.

A few minutes after sending the package through to Johannesburg for broadcast that December afternoon, I received a call from Nyana Molete, TV news editor. His first words to me were, ‘Calata, why do you want me to lose my job?’ – a question that greatly puzzled me because I did not wield such or any other power for that matter at the SABC. He then asked me to re-edit my piece and drop the footage of the EFF MPs chanting ‘Pay back the money!’ I declined. In the ensuing debate about journalistic principles and ethics, he asked me, ‘Calata, will you feed my children when they have to go to bed hungry?’ My response was that, although I would not like his children to go to bed hungry, I was not prepared to re-edit the piece. I claimed to have already left the office by then anyway. He said, in that case, the re-edit would be done in Johannesburg. I had no response to that, so I ended our telephone conversation.

A colleague, who was in the office with me at the time, overheard my conversation with Nyana. I suspect it was she who may have leaked my conversation with him to Andisiwe Makinana from City Press. Andisiwe called me barely half an hour later, asking me to confirm whether it was true that the SABC had banned the footage of EFF MPs chanting ‘Pay back the money!’ in the National Assembly. I confirmed to her that this was indeed the case.

The article appeared in the newspaper the following Sunday. Suffice to say, it didn’t go down well with the managers at the SABC. In the days that followed, both Isabelle and I were asked to explain in writing how this information got to the media.

About two weeks later, in January 2015, news management, in the person of parliamentary editor Vuyani Green, threatened us with immediate dismissal if we spoke out about internal SABC matters. This to me did not make sense at all, and I couldn’t for the life of me understand this logic. Our livelihoods were being threatened because high-ranking individuals in the SABC newsroom had taken unethical and, in some cases, unlawful decisions. Although they were meant to protect us journalists on the ground, they were the very ones selling us out.

These two incidents led to several more instances where some of my colleagues and I had to object to other unethical and unlawful instructions. Sometimes these were issued to us in the name of the ANC. I told Duarte that, as someone who was raised to believe that the ANC – the movement of my great-grandfather and father – could do no wrong, I had become terribly disillusioned by instructions from some editors to act in a manner that I knew was contrary to what I was raised to believe about the ANC.

Duarte on several occasions assured me that such instructions were never issued by the ANC and that those behind such actions were doing so of their own volition. She said media freedom and the independence of newsrooms, particularly those of the national broadcaster, were guaranteed not only by ANC policy but were in fact enshrined in our Constitution. Censorship was not.

Duarte then asked about our dismissals. Although there was nothing funny about this question, we managed to smile about it because we both knew what or whom we were about to talk about.

I proceeded to describe to her the disciplinary process or lack thereof in detail. I specifically highlighted to her how the SABC had in its haste to fire us flouted its own rules and regulations. Worse still was that the SABC had not only violated the country’s labour laws in the process, it had in essence violated our constitutional rights. I asked her how this had been allowed to happen in a democratic South Africa under the ANC’s watch. At this point, I could feel my anger and frustrations of the last few weeks bubbling to the surface. I was getting emotional. I hadn’t realised just how much the events of the recent past had affected me and the toll they had taken. But here I was, with a person of significant influence, who could potentially help me and my colleagues in our legal battle with the SABC. So I spoke from the heart and miraculously I didn’t cry. I still have no idea how I had managed to keep it together.

All the while, Duarte was desperately trying to keep up as she took notes of our conversation. At some point, she looked up from her notepad and asked what she and the organisation could do to assist me. I hesitated for a second or two, and responded that we needed help getting our jobs back. She immediately agreed to help. But there was a problem. She said she would probably only be able to assist Busisiwe Ntuli, Thandeka Gqubule, and me. The three of us were represented by our union, Bemawu (Broadcasting, Electronic, Media, and Allied Workers Union), in our labour dispute with the SABC.

Duarte said there was little she could do to help my other colleagues Suna Venter, Foeta Krige, Krivani Pillay, and Jacques Steenkamp, as they were represented by Solidariteit, an organisation which represents Afrikaner interests. She said it held ideologically different views to the ANC. I didn’t understand. And quite frankly, I didn’t want to understand and neither did it matter to me which organisation was representing whom. This had nothing to do with Solidariteit or any other organisation for that matter. I respectfully pointed out to her that I didn’t think it would reflect kindly on the ANC if it emerged that it had helped the three black journalists (two of whom, Thandeka and myself, had strong historical ties to the ANC) and not those from other races in the fight against the SABC. I impressed upon her the fact that eight of us were dismissed and that if she or the ANC was offering us help, they would have to help all eight of us, not just some of us. I was very pleased when she eventually agreed with me.

With this now settled and out of the way, we invited my mom and sister into the meeting. I’ve always known that my mother is a mighty soldier of a woman. I thank God every day that He chose her to give birth to me, raise, and guide me on this earth. In the meeting with Duarte, my mother once again proved just what a powerful force she is. She began by telling the DSG how she had read my letter in the newspapers and how she couldn’t understand why I had been dismissed based on what I had written in that letter.

For her, the parallels between my ordeal and that of my father were too much to bear. She then compared the circumstances between my father’s dismissal and mine, pointing out some uncanny similarities. She said that, at the time of my father’s murder, he had been waiting to be reinstated after being fired from his job as a school teacher in Cradock. Like him, I too had been charged, allocated a date upon which I would appear before a disciplinary hearing, and – once again like my father – I had been dismissed without my employer ever hearing my side of the story. To make matters worse, she said, on the day my father left our home never to return from a meeting in Port Elizabeth, I was just three years old and sick with the mumps. My three-year-old son, Kwezi, was sick with tonsillitis on the day I was dismissed. ‘Where is this all going to end?’ she asked, adding that she was praying not to have to relive the searing pain of death and loss again as she had done with my father.

After an emotionally charged two hours for all four of us around that table, the meeting ended with Duarte promising to do all she could to assist the eight of us fired by the SABC.

While in Johannesburg, I also wanted to meet with the lawyers who would represent Thandeka, Busi, and me in our Labour Court challenge. I had been a little annoyed with my union, Bemawu. In the hours and days after our dismissal, I had spoken to Advocate Dumisa Ntsebeza, whom I wanted to represent me in the case. Bra D, as he was commonly known, had had a long-standing relationship with my family and the other families of the Cradock Four. He and his brother, Lungisile, were arrested alongside Matthew Goniwe in 1976 for having been part of a ‘terrorist’ cell group. Bra D also later worked with my mother and the other widows when he served as a commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). I had specifically requested my union’s president, Hannes du Buisson, to brief Bra D for my defence. The union, in its infinite wisdom, had never done so, and this had pissed me right off. Instead, Busi, Thandeka, and I would be represented by a gravelly voiced attorney called Nick Robb from Webber Wentzel. I wanted to at least meet the man who would help determine whether or not I could return to my job at the SABC.

Nick turned out to be a really cool guy, excellent lawyer, and was best friends with Judge Clive Plasket, who had represented my mother and the other widows at the second inquest into the murders of the Cradock Four in the early Nineties. Nick opted to brief Advocate Steven Budlender, who was already representing Suna, Jacques, Krivani, and Foeta. After my meeting with him, I called Bra D to inform him of everything that had happened, and to express my sincere apologies to him as the union in this case hadn’t assented to my request. Bra D was very understanding and supportive, particularly when I told him that my case would be argued by Budlender. ‘You’re in very good hands with Steven,’ I recall him saying.

The case of the first four rebels, Suna, Jacques, Krivani, and Foeta, would be heard the following Tuesday with our case – Busi, Thandeka, and myself – scheduled for two days later. Vuyo Mvoko’s case was slightly different to ours – he would challenge his dismissal in the High Court, as he was on a fixed freelance contract at the time of his dismissal.

On Tuesday, 26 July 2016, four days after my meeting with Duarte, the Labour Court ruled that four of the SABC 8, Foeta Krige, Suna Venter, Krivani Pillay, and Jacques Steenkamp, be reinstated. This was obviously good news for all of us. The court ruling meant Busi, Thandeka, and I could also return to our posts at the SABC. Our case was due in court that Thursday, but our lawyers assured us that the ruling meant we probably wouldn’t appear in court, and that they would seek to have the first judgment made an order of the court. I was very happy not to have to go to court, particularly as this would’ve involved another flight from Cape Town to Johannesburg and back.

The SABC management, however, cut our celebrations and congratulatory messages short. Barely an hour after the court ruling, management announced they would appeal the Labour Court’s decision that we be reinstated.

Just like that, our jubilation turned to despair. We asked ourselves how the SABC with its depleting cash reserves could waste taxpayers’ money on a trivial matter like this. Did most of those ‘crazy baldheads’ on the 27th floor of the SABC offices in Auckland Park not know they were merely delaying the inevitable? Did they not know that we were on the right side of the law and history, and that it was just a matter of time before we would get our jobs back despite their obstinacy? Did they not know – or did they just not care? Well, I was ready to fight. Thandeka, Busi, and I were due in court for our case on Thursday, 28 July. We instructed Nick, our lawyer, to prepare to give the SABC a bloody nose. I was baying for it. On Wednesday, 27 July, the SABC suddenly backed down from its threats, announced it would not appeal the Labour Court ruling, and that we were free to return to our posts the very next day. This was such welcome news for all of us.

I suspected that this sudden about-turn may have had something to do with my meeting with Duarte, but I wasn’t sure how much of it did, and I never called to confirm if Duarte or the ANC had anything to do with the SABC’s decision to let us return to work. I was just so happy to return to my job. It had been an awfully tough few weeks. I wanted to put it all behind me. So on Thursday, 28 July 2016, I woke up, got ready, and went to the office instead of the Labour Court. Seven of us – Suna Venter, Krivani Pillay, Thandeka Gqubule, Busisiwe Ntuli, Jacques Steenkamp, Foeta Krige and I – went back to work that day. Sadly, Vuyo Mvoko did not. The SABC had found a loophole in his contract as a freelancer, which they could exploit to block his reinstatement at the broadcaster. Vuyo would eventually be vindicated when, over a year later, on 29 September 2017, the Supreme Court of Appeal ruled that the SABC was wrong in terminating his contract, which was valid until 2019, and ordered the public broadcaster to pay his legal costs.

Our first day back at work was just five or so days before the local government elections on 3 August. I remember being quite happy to walk back into the Marks Building in the parliamentary precinct, where the SABC’s offices are located. A few colleagues, Zalene Merrington, Pam Zokufa, Joseph Mosia and Abongwe Kobokana, were there when I walked in. The reception and their genuine happiness to see me back in the office made me feel so welcome. I spent most of the day catching up with colleagues and combing through hundreds of emails. I don’t recall doing much else that day. On the bus home later that evening, I thought back on everything that had happened over the past few weeks, what I had managed to pull off and how – to my own astonishment – I had actually accomplished some of the things I had done. I wondered if my father had been watching, guiding, and helping me along the way. I wondered too if he would’ve been proud of me.