Читать книгу My Father Died for This - Lukhanyo Calata - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Two

Оглавление‘He Was the Gentlest of Them All’

– Sarie Smith, childhood friend

LUKHANYO

This question is something I have often wondered about at great length. What kind of relationship would my father and I have, if he were alive today? My mother has told me about how happy he was when I was born, and that he always referred to me as his best friend. Would we still be best friends? Would we be almost like brothers? Would we get along at all? Or would we have a more conventional father-and-son relationship built upon well-defined boundaries of communication, personal interactions, and relating to each other?

Pondering these questions inevitably leads me to ask a number of other questions, such as: What course would our lives, specifically mine, have taken were my father still alive? Would I be the man I have turned out to be today? Would my dreams, aspirations, fears, beliefs, successes, failures be what they are? Would I have become a journalist? Would I have met Abigail? So many questions, which I will never have the answers to – at least not on this side of eternity.

I usually console myself by telling myself that I am the man God intended me to be. And just like any other person on this earth, I am shaped by my lived experiences to be the unique, beautiful soul that I am. Those lived experiences are what led me to Abigail, the second daughter born to Brian and Mary Isaacs. A beautiful young woman from Stellenbosch whom I fell in love with the very instant I laid my eyes on her in late January 2008. We were both younger journalists then, she a parliamentary reporter for the Afrikaans newspaper Beeld, and I a general news and sports reporter with eNews, as eNCA was still called then. We were sent to cover an ANC meeting in Philippi, a township just outside Cape Town. Mathews Phosa, who was elected treasurer general at the ANC’s 52nd National Conference in Polokwane in December 2007, was in Cape Town to deliver the movement’s birthday or its January 8th statement, as it’s more commonly referred to.

I remember that Sunday morning like it was yesterday. Abigail first caught my eye as she walked towards the area where a group of us reporters were chatting, while idly waiting for Phosa to arrive. At the time, both of us had been working as journalists in Cape Town for around five years, but that morning was the first time we’d met. I remember asking my colleague, Nawaal Deane, the cameraperson I was assigned with that day, who that beautiful woman was. I couldn’t keep my eyes off her. I knew I had to speak to her, so I waited for an opportunity when I could go over and at least introduce myself to her when she was alone. That opportunity never came, so I went over while she stood talking to Chantall Presence, a fellow journalist. I’m sure Chantall must’ve thought me very rude for interrupting them. Abigail later shared with me that she thought I was quite forward to intrude on their conversation like that. I introduced myself to Abigail and made sure that I complimented her beauty. She was then, and remains to this day, one of the most beautiful women I have ever seen.

Back in 2008, I was sharing a flat with my friend Koketso Sachane. He still teases me about that day when I returned home from work and couldn’t stop talking about this woman I’d met and whom I was convinced I would marry. Mind you, I knew very little about her. I had no idea if she was married, in a relationship, or gay – all I knew was that if there was any chance at all, she would become my wife. How this would happen was inconsequential. I had it bad. After our first meeting, I saw Abigail again a few weeks later. This time it was during the melee that followed the 2008 State of the Nation Address. The second encounter confirmed just how completely enchanted I was by her. A few days later, she gave me her business card. I don’t think I waited a day before I called to ask her out for dinner. I was more relieved than happy when she agreed. I remember telling anyone who cared to listen that I had scored myself a date with the prettiest girl. Abigail and I eventually married three years later on 24 September 2011. Over a year later, on 21 December 2012 she gave me arguably the greatest gift a woman can give a man, when she gave birth to our son, Kwezi Mikah Calata.

Our son’s birth that Friday afternoon brought me full circle. I, now, was the father to a little boy with all the responsibility that fatherhood and parenting carry with it. Although Kwezi’s birth in our flat in Mowbray remains the singular highlight of my life, I was then, and continue to be, daunted by the prospect of fathering him. How do I become the best father I can be when my father was not there to model what fatherhood is for me. My frame of reference for what fatherhood is, is largely pieced together from the odds and ends my mother has relayed to me over the years about the kind of man my father was.

Unfortunately, I don’t have any memories of the brief three years I spent with my father before he was murdered. Instead, my first and only memory of him is of his funeral.

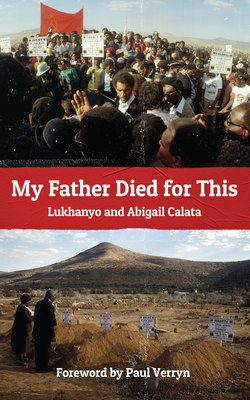

I’ve since come to find out that the date of his funeral was 20 July 1985. On that Saturday, I was just three years, eight months, and two days old. I remember it being bitterly cold. I remember the many, many buses and the thousands of people, some of whom had spent several days camped outside my great-grandfather’s home. My mother, elder sister, and I moved there at my father’s family’s insistence after his and Matthew Goniwe’s bodies were found five days after their disappearance in thick bushes just outside Bluewater Bay, a suburb of Port Elizabeth. I remember a moment when I clutched my mother’s dress so tightly as she sat sobbing in the back of a slow-moving, blue Mitsubishi kombi. Its rear sliding door was open and it was surrounded by thousands of people. I also remember being terrified at the gravesite that the ground underneath me would cave in and that I would fall through it as it shook from the force of toyi-toyiing comrades. I remember the choking dust. The red coffins.

Despite many desperate attempts over the years to conjure up memories of my father alive, I just don’t seem to have any. My most fervent wish is that I will remember something about him – irrespective of what that memory is, just as long as it is of him alive. I know it would be a memory I’d treasure forever.

An estimated 60 000 people from all around South Africa, and including diplomats from France, Norway, Denmark, Canada, Australia and Sweden, defied a government ban and travelled to Cradock to pay their last respects to my father and his comrades. The funeral is said to have been one of the biggest political funerals in the Eastern Cape, at least since that of the leader of the Black Consciousness Movement, Bantu Stephen Biko, in 1977.

Mourners had made their way to Cradock in trains, at least 160 buses, even more minibus taxis, and private cars. Newspaper reports and personal accounts claimed that many more people were stopped at roadblocks as far afield as Worcester in the Western Cape and ordered to return home.

ANC president Oliver Tambo called all the way from Lusaka, Zambia, to pass on his and the movement’s condolences to the people of Cradock. Zuko Vabaza was the one tasked to deliver the message from the ANC president to those attending the funeral. My sister Dorothy recalls how uBhut’ Zuko always joked he would never again wash his left ear because that was the ear he had pressed against the telephone when he spoke to OR Tambo.

On that afternoon, the mourners who had gathered in my hometown of Cradock in the Karoo – which was already such a thorn in the side of the apartheid government – sent PW Botha and his cabinet a message, louder and clearer than anything they had ever heard before. In a supreme act of defiance, those present at the funeral hoisted two massive liberation movement flags. One displayed the black, green, and gold of the ANC, while the other, almost one and a half times bigger, was red with a yellow hammer and sickle neatly painted onto it. In 1985, both the ANC and the South African Communist Party had been banned for well over 20 years. It was inconceivable at the time that these two flags would be hoisted inside the republic, never mind that they would be hoisted in a relative backwater like Cradock.

I guess it was inevitable that, just a few hours after my father’s coffin and those of Matthew Goniwe, Sparro Mkonto, and Sicelo Mhlawuli were lowered into their final resting places, ‘Die Groot Krokodil’, President PW Botha, would go on SABC radio and television to declare the country’s first (partial) State of Emergency in 25 years. The last State of Emergency had been declared after the Sharpeville massacre on 21 March 1960, a day that would prove one of the darkest in the country’s history. Sixty-nine black people were shot and killed during a protest march against apartheid-era pass laws. An estimated 180 others were injured in the senseless and wanton violence meted out by the police.

The 1985 State of Emergency started in 36 of the country’s 260 magisterial districts. The vast majority of the districts were in the Eastern Cape and included Cradock and its surrounding towns, Cookhouse, Somerset East, Graaff-Reinet, Steytlerville, Hofmeyr, Grahamstown, Port Alfred, Tarkastad, Bedford, and Adelaide. It included districts in the Witwatersrand and the Vaal Triangle (these areas are now part of Gauteng).

So, who was Fort Calata? What was it about his death alongside that of Matthew Goniwe, Sparro Mkonto, and Sicelo Mhlawuli that led to such anger, militancy, and large-scale defiance of the brutal apartheid government from South Africa’s oppressed people?

ABIGAIL

As much as this book is an attempt to tell Fort Calata’s story, it’s also an attempt to get to know the man. In my quest to uncover my father-in-law’s history, I listened intently to all the stories that would give insight into what kind of person he was. The longing Lukhanyo and I share to know the sound of his voice, how his singing voice differed from his speaking voice, what he smelled like, how firm his handshake was, or what he would have look like aged 60, will never be satisfied in this life. This realisation weighs heavy on my soul, and I can’t begin to know what this truth over three decades does to the people who loved Fort and then lost him in such a brutal way.

At four years old, Kwezi is at an age when he’s starting to grapple with the concept of death. He and Lukhanyo went to the grave on a recent visit to Cradock. He asked Lukhanyo, ‘Do you know what killed Fort?’ And proceeded to answer this question with, ‘The apartheid killed Fort.’ Lukhanyo and I were both surprised by this answer, and both of us assumed the other had given him an answer similar to this when Kwezi asked that question. But he’d come up with it himself. Neither of us had ever heard that question from him before, nor provided an answer resembling anything like that.

Kwezi also wanted to know from me whether Fort was with God in heaven. I told him yes, he was. He wanted to know whether heaven was a place where one ‘saw God for real’. I told him, yes, that is what you can expect, and this seemed to really please him.

By all accounts, Fort Daniel Nqaba Calata was a remarkable person. As a child he was introverted, but not unfriendly, and a bit of a clown. His late sister Peggy described him as, ‘talkative. He liked to joke around. He was nice to us, but he also liked to spend time by himself.’

Fort, his two sisters, Sisana and Peggy, as well as his brothers, Patutu (Patrick) and Roy, grew up with their cousins Mandisa, Gangumzi, Bangilizwe (Bangi), Nonthuthuzelo (Ntutu), and Nomzi. Their grandparents, James and Miltha Calata, raised all of them as their own children, while their mothers, Nontsikelelo, Vuyelwa, and Noluthando, were working outside of Cradock.

His cousin Bangi Solo remembered him as a ‘somewhat sickly baby’ who comforted the family after they lost baby Joy, Peggy’s twin sister. For Peggy, Fort filled the void left by the passing on of her twin: ‘Fort was very important in my life because he was my imfusi [the child born after twins]. In Xhosa culture, if one of the twins dies, the child who’s born after that must take the place of the late twin. That is how close I felt to him. You must also bear in mind how close we were in age. I was born in July 1955. Fort was born in 1956. We were, however, very different. I am an extrovert, while he was an introvert,’ she said.

LUKHANYO

The little boy who would one day become my father was born on the morning of 5 November 1956 to Nontsikelelo Gertrude Calata and Macdonald Maphike. He was their third child, born just over one year after twins, Peggy and Joy. Joy died while only a few months old. Nontsikelelo – or Sis’ Ntsiki as she was known – and Macdonald were not married, but lived together in Sophiatown, a vibrant black suburb just outside Johannesburg’s city centre. Both the little boy’s parents were musicians. Sis’ Ntsiki was a classically trained pianist, while my grandfather, Mac, was a gifted tenor saxophonist. Both, I am told, also sang quite well and played for several bands and groups in the area at the time. But under apartheid (and I guess even today), very few black couples could raise a family on musicians’ wages. So, my grandmother kept her day job as a primary school teacher, which provided the family with a steady income.

A few weeks after his birth, Sis’ Ntsiki took her newborn along when she visited her father, Canon James Arthur Calata, in detention. He had been arrested and was held at the Old Fort Prison on charges of high treason alongside 155 other anti-apartheid leaders. Among them were the likes of Yusuf Dadoo, Ruth First, Archibald Gumede, iNkosi Albert Luthuli, Nelson Mandela, Professor ZK Matthews, Vuyisile Mini, Lilian Ngoyi, Reginald September, Walter Sisulu, Joe Slovo, and Oliver Tambo.

It was during this visit when her father, or Tatou, as he was known by the family and the community of Cradock, named his new grandson Fort – adding that, like a fort, the young boy would become the strength of the family.

During this visit, Tatou also expressed his unhappiness regarding the family’s situation in Sophiatown. Just a year before, Sophiatown had been declared a white area under the Group Areas Act. By November 1956, when my father was born, the government had started its forced removals programme. Its bulldozers had moved into the suburb and had already begun demolishing families’ lives, dreams, and aspirations alongside their homes, schools, clinics, and other community structures and amenities.

This was not the life Tatou had wanted for his daughter and, more particularly, his latest grandson. I suspect the fact that Sis’ Ntsiki wasn’t married to Macdonald also weighed heavily on him; he was after all an Anglican priest. So, just days after their visit, he arranged for a group of Anglican clergymen to transport his daughter and her newborn son to the relative safety and peace of their home in Cradock. Here, Sis’ Ntsiki was eagerly awaited by her mother, Miltha Mary Calata, or Mamou as she was affectionately called. It’s unclear how many times the young Fort would see his father again, if at all, after this hastily arranged relocation to Cradock.

Tatou remained in prison for at least another year as the apartheid state prepared to prosecute him and his fellow detainees on charges of high treason. He was eventually released alongside OR Tambo, iNkosi Luthuli, and about 70 others in December 1957, due to a lack of evidence against them. Shortly after this release, OR Tambo went into exile. My great-grandfather returned home to his family, church, and community in Cradock. Fort’s cousins and siblings, my aunts and uncles, had over the years told me how energised Tatou was by having a baby in the house. By the late Fifties, Tatou was serving as senior chaplain on the ANC’s National Executive Committee. Walter Sisulu had succeeded him as secretary-general of the movement at the Bloemfontein National Conference in December 1949.

Despite his on-going health issues, family and community members in Cradock recalled that all Tatou ever seemed to do was work. Almost everybody we spoke to talked about the formidable organiser he was. One of these people was Mbulelo Goniwe, a childhood friend of my father’s and Matthew Goniwe’s nephew. I asked him what his impressions were of Tatou as he and Fort were growing up in Cradock’s old location. After a long pause, he said to me, ‘Tatou was the true embodiment of humanity. He was someone who loved children, who, despite being this well-respected person, often spent time talking to the youth, particularly about our education.’

Mbulelo recalled that at some stage Tatou owned a blue Ford Anglia, and that he and Fort had on more than one occasion had the privilege to accompany Tatou when he visited schools on several farms around Cradock. He said, ‘Tatou did not distinguish between his ministry and political work. Tatou also had a deep faith in future generations.’ Bhut’ Mbu, as I call him, then cited an example of the kind of attention Tatou would give to youngsters in Cradock: ‘Tatou would often stop to speak to us youngsters, and in the course of that conversation he would ask one of us whether we had eaten. I found him to be someone who had a genuine love for humanity and righteousness.’

This description of Tatou is corroborated by author Stanley Manong. In his book, If We Must Die, Manong writes of Tatou, ‘He was revered by everybody and became a people’s priest in the literal sense.’2

To the Anglican Church, however, Tatou’s duality – as a priest and politician – was a major concern. Bishop Archibald Cullen, based in Grahamstown, wrote to him on several occasions in a bid to have him scale down his political activities. Tatou, it’s said, would politely disagree and decline each time. Despite his busy schedule, Tatou took a keen interest in the upbringing of the young Fort. Mamou was very encouraging of this, as it meant her husband was spending more time at home than usual.

According to Fort’s cousin Bangi, they (the children) had to get used to seeing Tatou at home more often. Although Tatou was still working as hard as ever, he began to take meetings, mostly political, at home. Bangi added, ‘This meant a change in routine for everybody, especially us, the children. With Tatou at home, Mamou was stricter than usual. She demanded silence above all, so we didn’t disturb Tatou while he worked.’

ABIGAIL

Fort was perhaps the first of what I’ve come to term the Calata sons of favour, a status he shared with his son, Lukhanyo, and grandson, Kwezi. I became aware of this phenomenon after Kwezi’s birth in 2012. Our research revealed that from very early on Fort established himself as Tatou’s favourite – a fact confirmed by both Peggy and Bangi.

‘Fort was Tatou’s favourite because of that calmness. Parents will always have their favourite,’ explained Peggy. Fort was also the lucky recipient of any food that was left over on Tatou’s plate after dinner. And Bangi’s sister, Mandisa, surreptitiously passed her meat to Fort at mealtimes. She didn’t like meat and had an agreement with Fort that he would eat her meat. Mamou expected the children to eat all the food on their plates and therefore the cousins had to pass the meat secretly under the table.

Peggy remembered that Fort was the only one of the grandchildren who was allowed, to some extent, to interrogate Tatou’s decisions and teachings. Peggy cited several incidents of Fort’s pushing the envelope at times and posing rather difficult questions directed at his grandfather regarding the Scriptures they read at evening devotions or in church. Tatou always engaged Fort earnestly in debate, much to the annoyance of the older children, who were forced to sit at the table until Fort had asked the last of his ‘many, many questions’.

One such debate started when Fort questioned Tatou about a statement he’d attributed to Jesus in his Easter Sunday sermon. Peggy recalled, ‘Fort said to Tatou, “I do not understand when you say, when they crucified Jesus Christ, it is written, Father, forgive them for they know not what they do. Because that [the crucifixion] was planned.”

‘We were part of these arguments. Tatou would try to convince Fort of the way things were. Fort would say, “The bottom line here, Tatou, is that they planned and it was well planned, so it was not accidental. And for you to stand in front of the congregation and say, Because they know not what they do, I think there is something amiss there.”

‘That drew him closer to Tatou. We wouldn’t talk to Tatou like that. We’d tell Fort, “You can’t talk to Tatou like that,” but Fort said, “I want to get to the bottom of this because Tatou stood there and said, They know not what they were doing.”’

Of course, Fort was emboldened to question his grandfather like that because of the close relationship they had. This story also illustrates his bright, questioning mind. He didn’t take things at face value, even that which he heard from the pulpit, despite the reverence he had for the church and priest, who was both his spiritual and earthly father.

Sitting with Tatou while he worked or played the piano was a privilege none of the other children was afforded. Bangi explained, ‘Fort would just vanish, only for us to find him quite close to Tatou. He was a very quiet child and that’s what he used to do. Whenever Tatou was around, Fort vanished.’ At these times, Fort would be right there next to Tatou. He would just sit there listening, watching attentively, and trying to sing along as Tatou’s hands moved up and down the piano keys. Tatou would play and sing his original compositions or traditional church hymns. I can only imagine how the young Fort must have been musically educated and inspired by watching his grandfather during those moments.

Bangi added, ‘You know my grandmother was very strict. She didn’t want us to disturb Tatou because he was doing so many things, but Fort would find space [in close proximity to Tatou] and she eventually grew to accept that.’

The favour Fort enjoyed extended beyond the walls of his (grand)parental home. Fort’s arrival in Cradock as a baby coincided with a growing hope in the community that Tatou would be released from prison and everything would turn out fine. ‘When Fort first arrived from Johannesburg, community members came around [regularly] to hear the latest news regarding Tatou. That is why almost everyone had this attention for Fort all the time. Everyone, we all, had a very soft spot for Fort,’ said Bangi.

He went on to explain that their (the grandchildren’s) love for music was a direct result of Tatou’s love for music. ‘Every day Tatou came home for lunch and before he left he always played either the organ or the piano. That was how music came into our home. Because of Tatou, Fort started playing too. He went deeper and deeper into music, and by virtue of his being close to Tatou, I think he was like, “I must do everything this old man is doing,” to the extent that we all thought that one day he would also become a priest. Our nickname for him was Archdeacon.’

A childhood neighbour and family friend Sarie Miles (née Smith) remembered how Fort, shortly after starting at primary school, began to play piano. ‘He’d say, “Sarie, kom speel [come and play].”’ These play dates would happen mostly on Sunday afternoons once Tatou and Mamou had gone on home visits. She said Fort would sit at the piano and imitate Tatou, playing and trying to sing the very songs his grandfather did. She vividly remembered how the young Fort displayed musical talent back then already.

Sarie recalled it was Fort’s gentleness that drew her to him. They used to play a game where boys and girls would pair off. She always chose Fort as her partner. ‘He was such a gentle person. He was the gentlest of them all. He understood me,’ she said, smiling to herself.

Like his father, Lukhanyo is also a son of favour. I make this statement because of the obvious respect he commands in the family despite being among its younger members. Dorothy, who attended Peggy’s memorial service with Lukhanyo in September 2017, told me, ‘Afterwards, we got together with all the cousins, who came to Cradock for the memorial. Everyone wanted to greet and be acknowledged by Lukhanyo – or ubhuti as he is affectionately referred to in the family. It had nothing to do with his being on television or even the SABC 8 saga, and everything to do with the esteem in which he is held in the family.’

He hardly notices it – and if he does, he pays it no heed. Yet even older people outside of the family harbour a deep respect for him. He approaches people, both young and old, with great deference, and most times they reciprocate this respect even when they have never met him before and don’t know anything about him. It is quite something for me to behold, as the only people I’ve experienced being treated this way are clergymen.

Lukhanyo is Nomonde’s favourite, and his sisters, like Fort’s cousins before them, accept this fact with grace. I asked her once whether it was more a joy or pain to have a son who resembles his father in so many ways. She answered that having Lukhanyo has brought her more comfort, but that there are some moments when the pain of her loss is felt more acutely because of him. One of those times was the day of his graduation. ‘On that day he looked more like his father than he normally does. Also, when he got to the stage, he walked to the microphone to correct the pronunciation of his surname. I thought Fort would have done exactly the same,’ she said, recalling the pride and pain that pierced her heart at that moment.

As Lukhanyo’s wife, I too find myself on the receiving end of much favour from the Calatas. My mother-in-law completely embraces and loves me like her own. I am humbled by the high regard with which she and her daughters hold me and can only hope I don’t ever disappoint them, and, in doing so, lose that regard.

With all this favour surrounding us as a couple, favour upon Kwezi is inevitable. This favour is evident in the delight he elicits from my mother-in-law, her daughters, and their children. I expected Lukhanyo and me to delight in our son, but nothing prepared me for the pure delight Nomonde and her daughters find in him.

Tumani (my younger sister-in-law) would use the fact that she witnessed his birth to justify this reaction to her much-loved and cherished nephew. I once caught Dorothy casting a long, adoring look at Kwezi, who was busy with one of his favourite pastimes, drawing and watching television at the same time. Later, when I mentioned my observations concerning the Calata sons of favour, she drew my attention to that very look earlier. When I asked what had caused it, she answered, ‘Kwezi is a Calata in all the ways that really matter. Not only because he is Lukhanyo’s son, but also because he embodies the best of the Calata qualities. He is extraordinarily bright. I love how he reasons and questions things even at this young age. He’s talkative, like me. Why should I not delight in him? He is my brother’s son in every way – physically and in character.’

If Kwezi and his father are alike, Lukhanyo and his father are even more so. In the process of writing this book, I’ve come to greatly respect the Calata intellect. When speaking of the years at the Mission House in iLingelihle, and Tatou and Mamou’s persecution by the apartheid state, Peggy mentioned that as the children of so-called troublemakers, they did not have it easy at school: ‘The only thing that served us was that we were clever – we did our school work well,’ she explained.

Lukhanyo and his sisters are indeed very clever, but I believe they got it from both parents. Peggy remembered the time Tatou promised he would slaughter a sheep for each child who came first in their class. By then, the older cousins had left the house and there were only four of them staying with Tatou and Mamou. They were Peggy, Fort, their youngest brother, Roy, and cousin Ntutu. ‘We all knew that Fort would be the one [for whom the sheep would be slaughtered]. He was at the same time very calculating and plotted against Tatou.

‘He told us, “What if all of us came first? What would Tatou do if we all [obtained] first place? Would those sheep come? So, let’s try it.” That year, myself, Fort, and Ntutu came first in our respective classes and three sheep were slaughtered. We knew then we could take Tatou at his word.’

Peggy also mentioned that Mamou’s strict rules did not bother Fort too much. Being an introvert, he didn’t care to socialise outside of the house. This lack of interest in the outside world and people was not something he shared with his cousins and siblings, who very much longed to be part of the world beyond the four walls of their home. ‘There used to be what was called an afternoon spend [a dance for young people] in the [church] hall. We wanted to go there to show off our beautiful dresses, but we were not allowed to. Fort would be in the [bed]room reading. If he was not reading the Bible, he was reading his school books. We would try to convince Mamou [to let us go] because now we have finished our housework, but Mamou would hand us the Bible, saying we would never be finished with it. Fort would then laugh at us and say, “Come join me.” We were not impressed with him. If he wanted to be alone and close himself off in a room, let him be. We wanted to mingle with other children.’

Over the years, Tatou acquired several musical instruments and encouraged his grandchildren not only to learn to play them, but also to form a family band. Fort of course took this wish – and his interest in music – quite seriously.

‘Fort would never get out of the garage, where the instruments were,’ said Bangi. ‘If he was not on the keyboard, he was playing the guitar. When he was not playing the guitar, he was on the bass or the drums. He was teaching himself [to play]. There were some guys who at a later stage were helping him, but for most parts he taught himself.’

‘We mostly taught ourselves to play the instruments,’ added Peggy. ‘Fort was solitary. He liked spending time by himself. Sometimes Mamou would just decide, “Let us bring him food right there,” because it was useless to try and get him out of the garage.’

Bangi remembered that, though Fort was proficient on all the instruments, the keyboard remained his favourite. ‘Fort and Bhut’ Gangumzi were gifted singers. Sometimes they would fight about who would sing. Peggy also sang. Patutu and myself used to buy LPs on an almost weekly basis. American soul was popular back then – the kind of music you’ll hear these days on Saturdays and Sundays on [Radio] 702.’

Michael Allens, better known as Oom Kallie, was among those who played with Fort in the late Seventies and early Eighties. The band was called The Survivors. Oom Kallie was the lead vocalist with Fort on the piano. He recalled, ‘Fort, in most cases, was a better singer and player than other band members. He didn’t lord that over us, though, and was content to play whatever instrument he was required to play.’

The band that preceded The Survivors was The Heartbreakers, which was made up of musicians from the black township, whom Fort auditioned before they could join. According to a former band member Zolile Kota, also known as Zorro, the band practised quite religiously every afternoon after school.

Fort ended up becoming Tatou’s right-hand man. All the boys in the family were expected to serve as altar boys in the church, with Fort being the only one who stuck with it even after all his cousins and brother, Roy, had bowed out. Bangi elaborated, ‘He knew at which farm Tatou was going to preach this Sunday and the next. He was like Tatou’s PA. That was his focus and his music. He was a very orderly person.’

Fort even exhibited a tolerance for the white archdeacon who served with them, which his fellow altar boys did not share. ‘We had this attitude toward whites, and the archdeacon was a white person, [called] Heath. Now Fort was the only one who understood Heath, and sometimes we would just rebel and say, “No, we are not going to perform our service as choir boys. We are not going to dress up and help him in the altar.” It would be only Fort who was always willing to be there with Heath,’ said Bangi.

LUKHANYO

The relationship between grandfather and grandson grew stronger as Fort got older. He was a willing and receptive student, learning everything he could from the old man – be it music, politics, religion, or Xhosa culture and tradition. It didn’t matter; he soaked up everything. Everyone I spoke to agreed that Tatou was more a father than grandfather to Fort.

Bhut’ Mbu confirmed that Tatou and Fort were close. He said by the time he and Fort were teenagers, they had some sense of Tatou’s prominence in the ANC and that he was under constant surveillance from the police. So they, the young men of iLingelihle – and Fort in particular – were constantly at Tatou’s side. They believed nobody would harm Tatou in their presence. He chuckled softly when he recalled that they would have been unable to offer any physical resistance were there to have been an attempt on Tatou’s life in their presence. He added that as Fort grew up he became Tatou’s bodyguard.

Bhut’ Mbu was also convinced that these years at Tatou’s side served as my father’s political education, when he was groomed by Tatou to take over the political leadership in the community. He described Fort as being very secretive about politics. He believed this stemmed from my father’s understanding that the ANC was a banned organisation and therefore conversations about the movement or politics were only allowed under specific conditions.

Fort’s close relationship with his grandfather also had a rather undesirable consequence. On numerous occasions, he witnessed the brutality of the South African Police. As a former secretary-general of the ANC, Tatou, as you can imagine, was a rather high-profile target, particularly for the conservative or verkrampte whites in a small Karoo town like Cradock. Tatou had run-ins with the police on an almost daily basis and Fort was, more often than not, the only witness to this constant harassment over a long period.

Despite this, I think, it must have been wonderful for the young Fort to receive his political education and moorings from his grandfather, a man who would later be described as ‘one of the greatest sons of Africa’3. I often wonder if it was a conscious decision by both my father and his grandfather, or if it was fate that led to Fort’s being the one who would be handed the baton by his grandfather.

I’ve come to learn so much more about my father in the last few months. For instance, that he liked to suck his thumb as a young boy. That as a teenager he preferred to spend time with his grandfather than his friends. I’ve learnt that, much like me, he too never really had a relationship with his own father, but unlike me, he at least had a tremendous father figure in his grandfather.

As I learn and discover more about my father, I realise that in order for me to understand his character (his motivations, his ambitions, his fears, and shortcomings), in order to tell his story completely, I have to take a step back and tell the story of his grandparents James Arthur and Miltha Mary Calata.

Tatou and Mamou were the foundations upon which the family – not just Fort – built their political activism. This is their story.