Читать книгу Preaching Prevention - Lydia Boyd - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

The Politics and Antipolitics of Miracles

The story of the early years of the AIDS pandemic in Uganda is now well known, but the lived experience beneath the streams of data is still hard to grasp. By the early 1990s, in some of the hardest-hit trading centers of southwestern Uganda every third household had an adult member dying of AIDS.1 HIV prevalence rates were some of the highest in the world, nearing 15 percent of the national population.2 Communities were faced with rates of death and disability that can only be described as devastating. Uganda, a country in eastern Africa, would soon become all but synonymous with the virus. And yet, against seemingly unimaginable odds and during a decade of intense economic and political upheaval, Ugandans were somehow able to roll back the tide of HIV/AIDS. Years before the World Health Organization was able to mobilize a global response to the epidemic, and during a decade when U.S. federal policies addressing AIDS were all but absent, Ugandans living in out-of the-way places,3 far from the reaches of academic biomedicine, were winning the fight against this deadly disease. Beginning in the late 1980s the seemingly inexorable spread of the virus began to slow. By the early 1990s HIV prevalence in Uganda began to drop precipitously. This reversal was so dramatic, and so unexpected, that it has been dubbed a “miracle” of HIV prevention success. By the early years of the twenty-first century, Uganda’s national prevalence rate was well below 10 percent of the population, and the epicenter of the global AIDS crisis had shifted to other parts of the continent.

Uganda’s “miracle” catapulted the country to the forefront of debates over HIV/AIDS prevention—debates whose stakes grew higher as global funds for treatment and prevention grew dramatically in the decades that followed. This book is about the wakes produced as this miraculous story was reclaimed, retold, used to justify certain responses to the epidemic, and adopted by politicians on both sides of the Atlantic to buttress new forms of political capital and international influence. It is a study of an American AIDS policy’s reception in Uganda, and the ways in which a policy supposedly drawn from Uganda’s early success returned there to shift the landscape of HIV activism and advocacy, engaging and reshaping long-standing arguments about sexual morality, marriage, and gender relations.

In 2003, President George W. Bush reversed a long period of intermittent action and partial measures by announcing a global AIDS policy of unprecedented proportions. Using soaring, optimistic language, Bush proclaimed that the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) represented a “great mission of rescue” that would prevent new HIV infections and save the lives of millions living with AIDS around the world. To promote HIV treatment and prevention was to enable “the advance of freedom” itself, reasserting America as a beacon of “hope” in parts of the world wrought by the epidemic’s crisis.4 The scope of PEPFAR was indeed transformative, for the first time bringing effective treatment to millions of people living with AIDS in resource-poor countries. But PEPFAR was also controversial. Of the $3 billion reserved for HIV prevention programs in targeted countries, one-third of monies were earmarked for abstinence and faithfulness-only programs. Under PEPFAR’s guidelines, these programs advocated personal “behavior change” as a frontline defense against the virus. President Bush and his advisers argued that empowering individuals to practice better self-control—by delaying sexual debut and remaining “faithful” to spouses—was the best remedy for an epidemic that had confounded public health officials worldwide. But critics in the United States and abroad viewed these stipulations as needless restrictions on aid, siphoning money away from other types of prevention programs, such as access to HIV testing, the promotion of condom use, and broad-based sexual education.5 More pointedly, others argued that such stipulations were made solely to forward Bush’s political agenda, and especially to appease his evangelical Christian supporters, who had newly embraced the AIDS epidemic as the frontline in a battle to reassert religious values in American policy making.6

With its emphasis on self-empowerment and personal accountability as pathways to disease management, PEPFAR dovetailed with other trends in conservative American policy making of the 1990s and the early years of the twenty-first century, a period defined by neoliberal strategies emphasizing the weakening of state welfare and the expansion of global free-market capitalism. An ethic of “self-help” pervaded policy reforms of this period, cultivating individual will and personal empathy as stand-ins for diminishing state resources.7 Under PEPFAR the Bush administration emphasized approaches to AIDS prevention that were predicated on an individual’s ability to manage and control his or her own exposure to disease risk. The term behavior change, which became a touchstone in debates over AIDS prevention policy during this period, was appealing to its supporters for the ways it focused attention on individual autonomy in sexual behavior. Like U.S. welfare recipients, participants in PEPFAR-funded prevention programs were compelled to become more responsible for their own care. If one could make better decisions about when and with whom one had sex—if one could abstain, or remain “faithful” in marriage—HIV risk could in theory be reduced or eliminated.

PEPFAR’s “great mission of rescue” was intended to alleviate the far-off suffering of, most prominently, African victims.8 But if PEPFAR was in part a project intent on ending the suffering wrought by the epidemic, it was also something more than a humanitarian endeavor. It was a global health program of unequaled scope, a project that sought to intervene in behaviors and beliefs about sexual relationships, medicine, and family life in order to better address the crisis. American “compassionate” sentiment helped form particular approaches to international governance and aid, approaches that were invested not only in recognizing and alleviating suffering but also in managing and “empowering” suffering populations and individuals. This American response helped outline a particular object of its care—what I call the accountable subject: a model for healthy behavior that, as I will discuss throughout this book, conflicted with other approaches to health and well-being in Uganda. Accountability was an approach to public health that emphasized individual responsibility for disease prevention; one that envisioned the locus of disease risk in personal behavior and choice, rather than broader structural, economic, and social factors that might also contribute to well-being. It was animated by a Western cultural orientation to health that places value on the virtues of physical autonomy and independence. In Uganda, where health has long been considered in part a function of the social and spiritual relationships one has with others, a message of self-reliance as the best pathway to healthiness had its limits.

This book considers the effects of these shifts in U.S. policy making from the point of view of the Ugandan born-again Christian AIDS activists who embraced Bush’s restrictions on HIV prevention funding and celebrated what they termed a more “moral” approach to solving the problems of the epidemic. By 2004, when I began this research, Ugandan religious institutions, especially nondenominational and Pentecostal born-again churches, emerged in a way they never had before as key players in debates over AIDS prevention, seeking out newly available funds through PEPFAR to organize teach-ins advocating youth abstinence and protests against “sexual immorality.” Kampala’s university campuses were awash with prayer groups meditating on the value of “sexual purity.” Saturday night discos competed with gospel-infused revivals where students were admonished to “keep their underwear on!” Ugandan born-again Christian arguments about what constituted moral behavior were shaped not only by President Bush’s “compassionate conservative” intentions but also by long-standing debates over the nature of family and kinship obligation and the role of women in Ugandan society. Emboldened by the interest and attention of conservative American Christians, born-again churches in the capital city of Kampala became key sites where “accountability” was actualized and put to use by Ugandan youth, at times with unexpected results.

In its focus on Ugandan activists, this book takes up the adoption and implementation of a global health program by Ugandans themselves, tracking the ways international agendas are repurposed to address culturally and historically specific experiences related to gender, family, and sexuality. Public health programs, especially those like PEPFAR, which are concerned with the intimacy of family life and sexuality, are programs that forward powerful moral claims about what it means to act healthily. The seemingly unassailable ethics that underlie dominant approaches to global health today—particularly ideals like accountability—are never neutral. There is, to echo the anthropologist James Ferguson, a “politics and anti-politics” to global health miracles.9 That is, humanitarian projects like PEPFAR claim a moral imperative that seems to place it outside the realm of politics. To alleviate suffering is ostensibly an act beyond political motive, even as the compassionate sentiments that underlie such projects help shape particular approaches to governance. The story of Uganda’s early AIDS prevention success was a product of this antipolitical humanitarian realm: embraced as a politically disinterested story of human triumph even as it was used to buttress and validate certain approaches to care and humanitarian relief, approaches that worked to create particular kinds of subjects for American compassion.

If this is a story about the ways a health policy travels, it is also a study of how African recipients of a public health program took up and transformed a lesson about accountability, emphasizing both the appeal and the limitations of a global approach to AIDS prevention. PEPFAR was a policy that circulated, from its roots in Uganda’s early success to its formation in the United States, and back again; and with each iteration it was adopted and used by both Americans and Ugandans to forward their own ideas about the benefits of accountability, self-control, and “moral” behavior. PEPFAR’s emphasis on “behavior change” reflects the dominant ethos underlying approaches to humanitarian care and global health today, but it was, on the ground, an approach that was contested in practice, reshaped by Ugandan orientations to moral behavior and well-being that conflicted with the American ideal of “accountability.” In this sense, the story of PEPFAR challenges the unidirectional image of global health: one in which Western countries create and fund programs outlining models for care and healthiness and Africans simply adopt such models.

In the following chapters I explore how “behavior change”—with its particular emphasis on an ideal of personal accountability—was an approach to prevention that was formed by a historical moment in the United States and Africa. It was an approach characterized by neoliberal economic policies that emphasized the individual—rather than the state, kin group, or community—as the central agent in processes of development and social transformation. The shape of the “accountable subject” is evident everywhere now, from messages like PEPFAR’s, in which the self-controlled, abstaining individual is the key to disease management, to rural development projects where, as Tania Li has argued, individual will drives social improvement schemes.10 In Uganda, neoliberal policies have reorganized institutional and state apparatuses, but they have also effected changes in the experience of moral personhood and the evaluation of moral conduct. What sorts of subjects are made legible by approaches to governance that demand that subjects become more “accountable” for their care, and with what consequences?

The larger impact of humanitarian aid and global politics was felt not only in the presence of PEPFAR’s programs but in the changing nature of Ugandan society, where older values predicated on the interdependence of youth and elders were being challenged by discourses emphasizing an “entrepreneurial” spirit and the benefits of young people’s initiative and independence. “Accountability” was a discourse that stoked deep tensions over the costs and benefits of such changes to society. Young adults felt these tensions keenly as they struggled to imagine their own futures and families. Uganda’s born-again churches were at the center of these transformations, adopting a message of personal “success” and moral asceticism in the face of a rapidly changing social environment—where everything from gender equality to conspicuous displays of wealth provoked moral rebuke and concerns about the state of Ugandan culture and values.

These broader shifts in AIDS prevention and activism have affected experiences of health and well-being in Uganda. The emergent emphasis on individual will and personal agency helped reinforce a new and distinct way of being an ethical sexual subject in Uganda—one that diverged from other messages about moral conduct that existed alongside it. In Uganda, as in many African societies, the liberal ideal of the rational, autonomous person that animates so many modern institutions and values—from Western biomedicine to the project of human rights to the ideal of accountability itself—coexists with other models for personhood, and especially those that construe the person as defined not by the qualities of interiority and autonomy but instead by experiences of social interdependence and obligation to others. In Uganda, relationships of interdependence between members of kin groups and between patrons and clients are critical ways social actors constitute their place in the world, and forge a moral and social identity. Ugandan experiences of personhood were in many ways counterposed to the message of individual accountability and independence that the PEPFAR program promoted.

In Uganda, these older models for moral personhood became critical touchpoints in debates over the concept of accountability as both a mode of prevention and a model for behavior. PEPFAR’s emphasis on accountability could provoke dilemmas for Ugandan young adults, who were also taught that their assertion of independence, especially through their withdrawal from social and sexual relationships, could in certain instances be viewed as dangerous, immoral, or antisocial. In southern Uganda, where the pursuit of health has been characterized by one historian as a “collective endeavor,”11 how did people make sense of a message that emphasized autonomy in decisions about sex and wellness? This book concerns itself with these sorts of conflicts: What does it mean to speak of a “self-empowering” approach to health care? What sort of moral agency is being advanced by an emphasis on choice and self-control? How did young Ugandans navigate the underlying conflicts inherent in the message of accountability? And, most significantly, how did this message come to affect the politics and experiences of health, disease, and family life in Ugandan communities?

The argument of this book is twofold. The first part is that the accountable subject reflects a particular approach to governance that has come to dominate contemporary frameworks for global health. Today in Uganda, as in much of the world where humanitarianism is at work, demonstrating a will to improve is the way one becomes a visible subject for nongovernmental endeavors. In this new model, one’s claim to certain services—access to clean water, education, health care—is no longer the rights-based claim of a citizen, nor a claim rooted in forms of traditional community-based obligation. Rather, access to humanitarian and nonstate aid becomes dependent on one’s ability to demonstrate accountability for one’s condition, to be a good subject of compassion, and to be able to harness the will to be improved by a donor’s humanitarian attentions.12

The second and more prolonged argument of this book is that this approach to health and healing is animated by particular moral sentiments and ethical dispositions that are contested in practice. Decisions about health are broached as moral conflicts, and to understand the effects of a global policy like PEPFAR we need to better understand the diverse models for moral agency and personhood that define the pursuit of health in particular settings. In Uganda, the values that inhabited accountability—to be autonomous, self-sufficient—were experienced in tension with other ways of being that were also understood to define the experience of health. Health in Uganda was not expressed solely as the good management of one’s interior, physical state. Moral and physical well-being depended also on the proper management of one’s obligations to and relationships with others—relationships that were believed to directly affect one’s physical and mental state. If Americans attempted to forward an authoritative model of proper, healthy behavior marked by the emphasis placed on the virtue of being accountable for one’s own well-being, Ugandans engaged this message on more uncertain terrain. The rest of this introduction elaborates on these points and provides background information on the community where my research was conducted. I begin with a discussion of how and why accountability has come to dominate global approaches to health today.

The Accountable Subject: Biopolitical Aid and the Effects of Compassion

When I write about the “accountable subject” I mean to draw attention to a particular way of thinking about good and proper conduct—conduct that is thought to produce healthiness and prosperity and has come into focus in recent years in part through policies like PEPFAR. PEPFAR’s faith in individuals’ capacity to change—to reform their behaviors—formed the core of its policy directives.13 It was rooted in an underlying belief that both moral good and socioeconomic good follow from the actualization of ideals like independence, autonomy, and personal freedom. And it differs from other popular approaches to disease management—for instance, methods that encourage technological interventions, such as an increase in serostatus testing or the development of a vaccine, or methods that encourage structural changes that address socioeconomic or other inequalities linked to health risk, such as gender differentials in education or high rates of domestic violence. PEPFAR emphasized only one type of prevention approach in its funding stipulations, requiring that one-third of monies directed to prevention, US$1 billion, be used for “abstinence and faithfulness” education. So why—and why now—have the ideals of self-control and personal accountability come to govern public health regimes, especially those concerned with AIDS prevention?

An ethic of self-regulation seems to have intensified in recent years alongside changes to dominant forms of state and international governance. Beginning in the 1980s, two interrelated trends began to shift the field of economic development—and in turn, health care—in Uganda: the first was the expanding influence of a neoliberal economic doctrine, and the second was the emergence of a humanitarian ethos as a core component of transnational aid. To understand the present meaning of “accountability,” it is necessary to understand the ways in which it is a message shaped by these intersecting trends in global governance.

Neoliberalism is a term that has itself been the object of criticism for the ways it is often characterized as a monolithic global force by social scientists, a term whose meaning, in its all-encompassing influence, has become ambiguous.14 Neoliberalism might be most succinctly defined as a set of economic policies that came to dominate the spheres of transnational aid and global restructuring in the 1980s. The structural adjustment programs advocated by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, and adopted by aid-recipient countries like Uganda, included provisions that sought to “rebalance” a country’s economy, usually by recommending various fiscal austerity measures, including the deregulation of industry, privatization, and the lowering of tax burdens for foreign investment.

Scholarly interest in neoliberalism has concerned itself with the social and political effects of these economic measures, and especially the ways this particular brand of economic calculation has transformed approaches to governance.15 Building on the earlier work of Michel Foucault,16 these authors have focused attention on the ways a certain type of economic rationality has come to encompass aspects of life previously considered outside the domain of the market. David Harvey’s oft-cited assessment defines neoliberalism by the core assumption that “individual freedoms are guaranteed by freedom of the market and of trade.”17 Nikolas Rose similarly argues that neoliberalism cultivates an approach to governance that reconceptualizes social behavior “along economic lines—as calculative actions undertaken through the universal human faculty of choice.”18 In this schema, rational choice is imbued with a moral value. Proper conduct is outlined by the ability to self-regulate and make “productive” choices. If people are “freed” to choose for themselves, they will learn to better govern and self-regulate their conduct.

Given this emphasis on rational choice, projects of development and economic restructuring in the neoliberal state have come to emphasize the individual, rather than the state or community, as the central actor in projects of social transformation.19 Daromir Rudnyckyj, writing about similar economic changes in Indonesia, calls this period the “afterlife of development,” an era marked by the shift from state-sanctioned investment to an era in which “this duty is transferred to the citizens themselves,” who are made to feel both more empowered and also more accountable for state services that may no longer be taken for granted.20 It is this aspect of neoliberalism that interests me. What happens when the pursuit of health in a place like Uganda is viewed through the lens of the rational individual decision maker?

The realms of biomedicine and public health may be particularly fruitful arenas in which to explore this emergent emphasis on individual accountability. Foucault’s lectures on “biopolitics” have highlighted the ways the physical body have become a more explicit focus of governance in the modern era.21 Biopower, according to Foucault, is enacted both in the policies that manage populations (such as those that regulate reproduction and population growth) and in the new ways individuals are taught to regulate and manage the body itself. More recently, scholars have proposed concepts such as “biological” and “therapeutic” citizenship to describe how biology and physical need have become key resources through which individuals stake claims to state and nonstate resources.22 If the body has become a more explicit focus for rights and regulations, it is also now increasingly conceived of as an optimizable resource.23 We are taught not only that we are responsible for ourselves but that our bodies and our experiences of physical health are the means through which we may improve and become more responsible citizens. As perhaps they have never been before, our bodies are the means by which we are governed and learn to govern ourselves.

When I note that PEPFAR’s key prevention message of “abstinence and faithfulness” may be analyzed as biopolitical sexual discourse and practice, I mean to draw attention to the sorts of ethical dispositions that abstinence and sexual self-regulation were supposed to generate: the intense focus on individual conduct as a site of economic and social transformation. In Uganda, particularly in the churches where my research was based, abstinence and marital faithfulness were spoken of as embodied practices believed to make people not only more moral but more economically successful; more “intentional” in decisions about work, family, and relationships; and more accountable for their mistakes. Abstinence and marital faithfulness were believed to cultivate a new, more productive young adult, empowered to embrace her own potential, more self-reliant, autonomous, and “invested” in herself. This rationalization of conduct was undertaken often at the expense of other ways of addressing social crisis: through forms of community organizing or large-scale structural changes to government or state. The “accountable subject” reflects these particular ideas about health and wellness, the ways that Ugandans in the early years of the new century were being taught, and at times were refiguring, a message that told them they could be empowered by making better personal choices about their bodies and avoiding the risks associated with disease and infection.

If neoliberal rationality and new forms of biological governance have given shape to the present-day onus on personal accountability, the accountable subject has also emerged in tandem with a particular humanitarian ethos that has refigured international aid and the relationship between Africa and the West. The changes that followed the adoption of structural adjustment in Uganda may be most noticeable in the mechanisms that organize aid and relief operations in Uganda. In President Yoweri Museveni’s first decade in power, international donor aid to Uganda expanded more than tenfold.24 But beginning in the 1980s, donor countries increasingly sought to shift grants away from state-led development programs and toward a development sector dominated by nongovernmental organizations. The privatization of aid has been swift and dramatic in places like Uganda. Between 1990 and 1998 the total amount of aid managed by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in Africa more than tripled, from US$1 billion to US$3.5 billion.25 During a similar period the World Bank saw a fourfold increase in the percentage of its projects managed by NGOs, from less than 10 percent in 1990 to more than 40 percent in 2001.26

International aid has not only been directed toward a more diffuse, privatized sector but has also increasingly been defined to address “humanitarian,” rather than explicitly political or economic, needs. The pursuit of health in the Global South has been especially affected by such shifts. HIV/AIDS, an epidemic of unprecedented proportions, has caused a state of crisis that demands immediate intervention. Health is imagined in this context not as a project of optimization, as it is in wealthy countries, but as one of exception. Humanitarianism may be distinguished from other historical and philosophical approaches to transnational aid by its explicit concern with human suffering. In the humanitarian state, physical need is the central recourse through which citizens and others make claims to scarce therapeutic resources and other forms of government care.27 This state of crisis creates a differential in treatment that distinguishes experiences of health and disease in places like Uganda from those in the Global North. Anthropologists Miriam Ticktin and Vinh-Kim Nguyen have argued that the act of linking aid to a demonstration of acute physical distress is problematic because the very exceptionality of this state closes off other ways of advocating for rights and access to care. In his study of AIDS treatment programs in West Africa, Nguyen asks, “What forms of politics might emerge in a world where the only way to survive is to have a fatal illness?”28 What does it mean to view health as a state of exception, and health care as a practice pursued through a lens of “experimentality,” a term Adriana Petryna uses to point to the inequalities that shape global health and medical research?29 The global health industry—which extends beyond humanitarian aid to include medical research, a realm where seemingly marginal and unregulated, yet needy, populations like those in sub-Saharan Africa figure prominently as test cases30—has helped refashion what it means to be healthy, and how healthiness is sought out, in places like Uganda. The accountable subject is also a product of these developments, where healthiness is pursued on paths of limited resources, and where the ability to demonstrate need, and become an “appropriate” subject of care, matters most.

Both neoliberal governance and humanitarian compassion helped shape new ways of thinking about being a good, proper, and moral person in Kampala. But as may already be apparent, the terms compassion and accountability are embedded in particular frameworks for understanding persons and agency that were far from universal in Uganda. A key tension that surrounded the adoption of behavior change emerged from its difference from—and occasional overlap with—other ways of acting as a good, productive, and moral person. As I will discuss throughout this book, the practices attributed to being an accountable subject were contested, emerging as an assemblage of global policy and local moral subjectivities that reshaped Ugandan orientations to health and well-being in the years following PEPFAR’s adoption.

Morality and Public Health

The first part of this book’s argument, which I have outlined above, is that PEPFAR is a policy defined by the conjuncture of neoliberal economic forms and an emergent humanitarian ethos in international aid, which together have helped outline the accountable subject at the center of global health. The second part of this argument is that the neoliberal concern with accountability is one animated by moral sentiments that were contested in practice. Public health programs, especially those that seek to prevent disease, are projects that intercede in broader moral debates, creating models for behavior that outline individuals’ responsibilities to themselves and to each other. The message that PEPFAR forwarded—to become more accountable for one’s health by avoiding HIV/AIDS—was a choice that was constrained by a number of economic and social factors. But abstaining, and becoming accountable, was also a choice that was viewed as a pathway to being a certain type of (moral) person in Uganda. Throughout this book I consider how decisions about health are often experienced as moral conflicts that highlight competing models for how to be good, healthy, and successful. To better understand the ways public health messages are interpreted in varied cultural settings, we need to be better able to recognize the role of diverse models for moral agency and personhood in the pursuit of health and wellness.

When I use the term public health, I refer specifically to the Western discipline familiar to most readers, under which a program for AIDS prevention, like those supported by PEPFAR, might fall. But the term also relates to a broader category of projects encompassed by the terms social health and public healing,31 which have been used to describe African practices of healing as collective endeavors, ones that are at the center of projects to maintain and secure social welfare. Neil Kodesh’s study of public healing rituals in precolonial Buganda has highlighted the ways that such rituals emphasized the connections between “a community’s moral economy and continued well-being.”32 Studies of healing in Africa have long underscored how practices that seek to manage health extend beyond addressing the physical ailments of suffering individuals to consider the broader social and moral context of health and prosperity.33 In communities across Africa, people’s relationships with each other, with a spiritual realm, and with their environments have long been factors that were considered to shape and intervene in experiences of health and illness. Even as there is much to distinguish modern public health projects from this longer history of African public healing, both sorts of projects attempt to forward a notion of social order that is predicated on specific moral orientations and sets of obligations.34 Modern public health projects set out to teach people to subordinate their personal desires and interests for the broader public good: “Cover your mouth when you sneeze.” “Kitchen workers must wash their hands before returning to work.” Public health programs are also projects that seek to inculcate models for healthy behavior within the public or social (and moral) context that gives our experiences of healthiness and social obligation shape.

Given this broader context, this book explores what a more explicit consideration of morality might bring to our understanding of health, and of global health programs in particular. To understand how AIDS prevention messages were engaged by Ugandan youth, we need to understand not just how health and well-being are linked to clinical practices or evaluations of physical risk but also the ways health is also a product of “moral imaginings and moral expressions.”35 Our moral perspective on the world, or what the anthropologist T. O. Beidelman has called our “moral imagination,” is the frame through which our experiences of sickness and healing—in fact, the entirety of our social world—is defined and coped with.36 A central aspect of the human experience is the way we confront uncertainty through practices of moral reflection: we imagine and speculate about others’ and our own pain and suffering. Our moral imagination also provides us with the ability to “scrutinize, contemplate and judge” our world,37 to imagine what is and what might be different. It may be understood to “map the ambiguity of social experience”;38 it is how we make sense of uncertainty and change. Perhaps because of this, anthropologists’ interest in the topic of morality has focused in particular on the problems of navigating and making sense of radical social changes. In several recent ethnographies, the study of morality has provided a way of understanding and analyzing the contradictions between indigenous ways of life and the ethical orientations associated with modernity.39 This has been especially true of studies of contemporary Islam and Christianity.40 Christian conversion has been noted for the ways in which it can precipitate a radical reconfiguration of social and cultural forms, marked especially by a sense of discontinuity between older values predicated on social cohesion and interdependence, and a modern-Christian emphasis on the value of individual agency, moral interiority, and personal autonomy.41

As much as social changes and social crises (such as the AIDS epidemic) have elicited a sense of disjuncture and discontinuity, in practice such conflicts are almost never experienced as linear and distinct.42 One benefit of a focus on the ways people engage moral norms is that it provides us with a more nuanced understanding of how individuals make sense of social changes and the competing values attributed to different ways of being.43 The crisis surrounding AIDS and its prevention is addressed on such moral terms in Uganda not so much as a problem of right and wrong, or as a problem addressed through the dictates of a certain religious doctrine or biomedical decree, but on terms that seek to define and establish the outlines of personhood and moral obligation. In the communities where I worked, I found that the American emphasis on accountable behavior was taken up and transformed by youth as they pursued multiple, often contradictory, messages about how to be good, healthy persons. As much as abstinence seemed to emphasize a neoliberal focus on the individual, in practice it also reinforced other, older models for sexual subjecthood. For instance, as I discuss in chapter 4, Ugandan youth viewed abstinence as something more than the cultivation of self-control and personal responsibility. They also viewed abstinence through frameworks for spiritual and community well-being that emphasized the strength of an individual’s relationships with others. As an embodied practice, abstinence (along with its partner message, faithfulness) mediated between the seemingly opposed experiences of autonomy and interdependence in neoliberal Uganda and the cultural and ethical meanings that lay beneath both ideals. A focus on the moral conflicts that are rooted in neoliberal approaches to governance and global aid provides us with a better understanding of the effects of such policies and of the role of African subjects in implementing and transforming these projects.

In the pages that follow I consider how health is pursued as a component of moral personhood and explore abstinence and marital faithfulness as ethical practices—or, following Foucault, “technologies of the self” by which young Ugandans sought to make themselves into certain kinds of moral persons. Foucault’s notion of ethical practice—that ethics is a matter of self-cultivation governed by practical “techniques” that guide conduct—has proved valuable to anthropologists because it establishes an understanding of ethics that emphasizes the quotidian practices that generate culturally variable ethical and moral subjects.44 Such analysis allows us to understand moral behaviors and choices not only as products of sovereign will governed by Kantian reason but also as actions shaped by variable forms of social power. In this schema, ethical practice may be analyzed as generative of multiple experiences of personhood, not dependent on a privileging of the autonomous post-Enlightenment individual.45

This is a focus that allows for a more nuanced understanding of the effects of public health policies that are enacted within diverse social and cultural frameworks and by persons who are motivated by multiple models of health and moral agency. This approach also enables us to explore how moral practices may be challenged, and how two overlapping moral systems may be navigated by social actors. In Uganda, the outlines of the accountable subject were encountered by youth in and through their efforts to abstain and be faithful, but these practices were complicated by efforts to manage competing models for personhood and competing outlines of what it meant to be successful and ethical in Kampala today. Only by understanding the underlying logics and moral orientations that Ugandan youth brought to the practice of abstinence can we fully understand the limits and possibilities that the message “abstain and be faithful to avoid HIV/AIDS” might have—in Uganda and elsewhere.

Moral Authorities: Born-Again Churches and Social Protest in Uganda

In Uganda the moral conflicts that surround AIDS prevention have been shaped by broader changes to Ugandan society since the 1980s. The epidemic coincided, as it did on much of the African continent, with a period of rapid urbanization that precipitated widespread alterations to social bonds. Family relationships were especially burdened by the epidemic, as exceedingly high rates of death and disability forced people to rely on extended relationships of kin and community in order to cope. But the changing nature of these same relationships—as young adults delayed marriage and women left their natal homes to find wage labor—also stoked concerns that the abandonment of “traditional” values was a cause of the disease and society’s misfortune. “Loose women” and “unruly youth” were a frequent target of blame for the virus in Uganda, as they were elsewhere.46 Because it became associated for many—especially elders—with changing family dynamics and the perceived misbehaviors attributed to newly more independent women and young adults, the epidemic intensified questions about what types of persons are morally correct in Ugandan society and about the social costs of both modern and traditional ways of being. These practices of reflection have especially engaged the spiritual realm, and blame for sexual misconduct has in some instances, as Heike Behrend has recounted in her study of Western Uganda,47 been attributed to occult forces at work in society. High rates of death during the epidemic fueled a sense of intense social, moral, and spiritual insecurity.

This sense of insecurity has also been exacerbated by the instability of the promises of new forms of global governance and political economy in neoliberal Uganda. Ugandans today live during an era when material wealth is both more visible and far out of reach for most people. The youth I studied, who lived in Uganda’s largest city and who were mostly enrolled or recently graduated from the country’s most prestigious university, regularly expressed a sense of frustration with their prospects for success despite their relatively privileged positions. Levels of unemployment were extremely high, and youth were forced to depend for extended periods on their parents and other elders for support. There was a growing sense of ambivalence about both an older generation’s emphasis on traditional social obligations and the modern emphasis on personal empowerment and individualism inherent in policies like PEPFAR.

It was into this environment that a born-again movement to prevent AIDS took shape in Uganda. The growth of a religiously oriented AIDS activism in the early years of the twenty-first century points to the expanding importance of spirituality as a mode of social critique in neoliberal Africa. A number of scholars have emphasized the ways that criticisms of contemporary conditions by Africans are taking new forms, focused less on tangible actors and more often now articulated through the “sacrificial logic” of Pentecostal and occult imaginaries.48 Such analysis challenges assumptions about the oppositional relationships between faith and reason, and religion and politics, to uncover how the spiritual realm has become a critical field in which Africans engage the problem of the moral uncertainty of political power. Spirituality is central to our understanding of how young adults in Uganda manage the contemporary sense of material and physical crisis, the tension and ambivalence that characterizes the neoliberal promise of self-help, and the behavioral ideal of accountability.

My interest in the world of born-again Christianity is with the ways such communities provided a model not only for moral behavior but for “moral ambitions” and ways of effecting or responding to social change that many Ugandans found objectionable.49 Omri Elisha, in his study of socially engaged evangelical Americans, uses the term “moral ambitions” to “draw attention to the intrinsic sociality of such aspirations . . . their inexorable orientation toward other people and their inalienability from social networks and institutions.”50 In Uganda, moral ambitions have long played a central role in the politics of the colonial and postcolonial state. In his recent history of colonial protest in eastern Africa, Derek Peterson argues that mid-twentieth-century political innovation was not centered in the struggle for democratic rights and independence but instead in the moral arguments that engaged anxieties related to changes in intergenerational and gender relations.51 Arguments over women’s newfound independence and youths’ perceived unruliness became ways for men to reassert their moral authority and to take control of a narrative of historical change. Like Elisha, I see the support of abstinence as an ambitious project engaged in by born-again youth, one through which they sought to enact ethical reform on themselves and, in the process, to transform society.

In this way, this book engages broader questions about the meaning and effect of a seemingly expanding religiosity in the modern world. Far from Max Weber’s prediction of a “disenchantment” with belief, Ugandans and Americans alike have embraced new and old forms of religious practice to make sense of, and even forward, a neoliberal emphasis on rationality and self-help. PEPFAR was a policy that sought to transform the ways communities and governments responded to social problems by seeking to funnel money to community and religious organizations directly and by targeting faith as a basis of social transformation. By focusing on a community of religious activists who responded to PEPFAR’s call to action, this study illuminates something about the role of religious practice in contemporary international aid. I examine churches as places where politics happens in mundane but transformative ways: in lessons about sex, family, and marriage; and in the support of certain types of relationships over others. In this broader sense this study builds on questions about American evangelicalism and social activism today, but places these questions in a very different social and historical context than that of the United States—one governed by quite distinct models and orientations toward religiosity, sociality, and morality.

This study also takes up questions about the nature and effect of the financial and personal relationships between American and Ugandan Christians. Since the 1970s, American Christians have become more active in political issues and social activism, a historical shift that has drawn extensive scholarly interest.52 But their efforts to engage Africans and others in their political projects—efforts that have become increasingly important to American Christian communities—have thus far received less scholarly attention. The recent controversy over Uganda’s antihomosexuality legislation, which I address in chapter 6, drew popular attention to the depth and impact that such intercontinental religious ties may have. My interest is not in the Americans who become involved in African affairs by donating money to churches, by supporting or withdrawing support for legislative efforts like the recent Anti-Homosexuality Act in Uganda, or by traveling in groups to volunteer in Ugandan communities. My concerns are instead with how American Christian perspectives are taken up and transformed by Ugandans themselves.

Research Methods and Fieldwork Engagements

I began field research for this book in July 2004, just months after the PEPFAR program began to disseminate funds to program partners in Uganda. I first became interested in PEPFAR after I spent that month interviewing North American missionaries about their work in the development sector. The PEPFAR program, and AIDS prevention and care work, emerged as a frequent topic in discussions with these missionaries, who were newly motivated by the program to respond to the AIDS crisis. Their newfound interest in the epidemic raised questions for me about the impact of PEPFAR and the meaning of the expanding influence and involvement of Christian communities in AIDS prevention work in Africa. When I returned to conduct fieldwork in October 2005, I based my research in Ugandan church communities that were involved in promoting youth abstinence in Kampala. One church, University Hill Church (UHC), became the focus of my fieldwork and is featured prominently in this ethnography. Two other churches where I spent time are not described at length in this book, though my experiences there and the interviews I conducted with youth in those churches have contributed to the analyses I include here. One church identified as Pentecostal and the other two as nondenominational, though all belonged to the family of born-again churches that Ugandans consider distinct from the mainline mission churches—Anglican and Catholic—that have been dominant religious institutions in the country since the colonial era.

UHC was located near the Wandegeya neighborhood in Kampala and served a mostly English-speaking population. This is significant because English-language-dominant churches catered to a more educated, and thus elite, population than churches that primarily used one of Uganda’s indigenous languages. This was a church that had been positioned to serve a growing population of educated urban youth in Kampala, and many members of UHC were drawn from the city’s university campuses, especially nearby Makerere University. While the church comprised a multiethnic Ugandan community, the culture of the Ganda ethnic group dominated,53 in part because the church was led by a Ganda pastor and in part because the church itself, like the city of Kampala, is located in Buganda. For this reason, in this book I draw on literature from throughout the region to describe Ugandan cultural attitudes and orientations, but I sustain a focus, especially in the historical analysis I provide in chapter 2, on the literature of southern Uganda and especially Buganda.

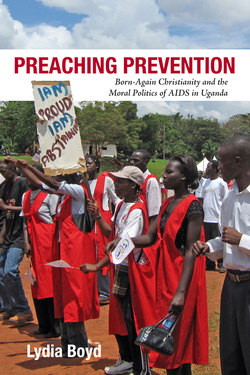

UHC, as well as other churches I visited and spent time in, was actively involved in AIDS prevention activities. Over the course of my fieldwork, UHC sponsored and organized abstinence education projects, including public marches, concerts, workshops, and outreach and counseling programs. UHC was also the recipient of a modest amount of PEPFAR funding, which was received via a church-founded NGO that had been named the recipient of a grant for abstinence education. Because of the relatively sensitive nature of my research topic—which touches on spirituality, sexual relationships, and disease—both interviewee names and the names of churches remain pseudonymous for reasons of confidentiality.54 I will describe UHC more fully in chapter 3.

For nineteen months between October 2005 and May 2007, I spent time in these communities, interviewing pastors and youth and attending services, workshops community events, prayer meetings, and women’s meetings. I also lived for nine months in the home of a Ugandan family who were members of a born-again church I visited regularly, and I attended home Bible study groups and family meetings with them. (I later rented for a year a small house adjacent to the home of another member of the same church.) I returned in July 2010 and June 2011 to conduct follow-up interviews with pastors and youth. I also spent time during those visits attending parenthood workshops at UHC, where I learned more about the church’s expectations for family life. I conducted group interviews with both church members and Ugandans outside the born-again community that focused on the issue of homosexuality and Uganda’s 2009 Anti-Homosexuality Bill, a topic I take up in chapter 6.

I interviewed four dozen young adults and reinterviewed ten of them at least twice over the six years of primary field research, tracking how their attitudes about marriage, sexuality, and their desire for and struggles with parenthood and family life changed over time. I also interviewed eight pastors and church leaders about their hopes for their church, their involvement with AIDS prevention and activism, and their problems with church financing. I knew many more young adults, older adults, and clergy less formally, and spoke with them at church meetings and social events about their concerns in life. In addition to ethnographic fieldwork and interviews, I also interviewed individuals involved in AIDS prevention outside these churches, including people involved in advocacy and research from various other sectors including academia, the secular NGO world, and the mainline Catholic and Anglican churches.

I was positioned as a researcher within the church community I studied, though—especially by those I lived with and knew well—I was also considered a friend. The intimacy of the ethnographic encounter can be both tremendously rewarding and challenging, as frustrating as it is illuminating: it is a mode of research that generates close personal ties between researchers and research participants. Ethnographers depend on the intimacy of the fieldwork experience to help reveal deeper cultural understandings: How do people in this community think? What matters to them? As Clifford Geertz has famously described, ethnography is akin to “thick description”; it is the way we come to understand the difference between the proverbial wink and a twitch of the eye.55

In recent years, especially as the work of religious activists in Uganda has generated more controversy (see especially chapter 6), many people have asked me what it was like to conduct fieldwork within this community. Studying Ugandans who have embraced a version of the religiosity—born-again Christianity—that many (Ugandans and Americans alike) view as native to my own country certainly presented its own unique challenges. The church where I conducted fieldwork had relationships with Christians in the West, and so the presence of an American in church was not all that unusual. As a researcher rather than a missionary-volunteer I was, of course, positioned differently from most of these other visitors. (I am not a born-again Christian, for one thing.) Yet as many other anthropologists who have studied Christianity around the world have also noted, my position outside the “frame of belief” was not a point of particular concern or contention for the Ugandans I knew.56 As a participant-observer I was taken seriously as someone who sought to better hear and understand the Ugandan Christian way of life. Church members took time to explain their mode of worship, their attitudes and beliefs, in part because this was the work of being a Christian—of both proselytizing and experiencing their own faith.

I was not only viewed as a potential convert (as all nonbelievers are), however; I was taken seriously as an anthropologist. This was somewhat surprising to me, as anthropology is not a discipline that is widely studied in Uganda (though, like foreign missionaries, the peripatetic academic researcher is a known commodity in Kampala). Thomas Walusimbi, the head pastor at UHC, once told a room full of church members that he wanted to start a college radio station and feature on it a show about “anthropology and our culture.” Though surprising, his idea was not all that far-fetched. The study of culture—especially as it was understood in Uganda to mean “traditional culture”—was a project of some significance to a community that sought to both embrace and reform aspects of so-called traditional life. Pastor Walusimbi even once spoke to me, unprompted, about the “anthropology of the Baganda,” forwarding his own analysis of the ways precolonial Ganda political relationships influence contemporary mind-sets. As a discipline concerned with understanding both the similarities and the differences between Ugandan and American Christians, anthropology presented a certain utility to the pastor. As I discuss in chapter 1, he was concerned with highlighting the agency of Africans in a world that seemed defined by the politicoeconomic relationships of development aid that positioned Africans as passive recipients; thus, a project focused on a deeper understanding of African actors was one he could get behind.

That being said, it was not always easy to observe and seek to understand views that were not only different from my own but at times objectionable and unsettling to me. The most challenging portions of my fieldwork were those toward the end of my study, when an antihomosexuality agenda came to dominate church activities. Both within and outside the church, discussion of homosexuality in Uganda revolved around often disturbing and violent imagery. Attacks on people accused of being gay or lesbian were becoming more common in Kampala in the wake of 2009’s antihomosexuality legislation. But it was during this period that I was also struck by the way Ugandans (and especially Ugandan Christians) were being portrayed by the Western media. They have become, to use a phrase coined by the anthropologist Susan Harding, a “repugnant cultural other” in the eyes of a supposedly enlightened West.57 Their views on homosexuality have been dismissed as either grossly misguided, a symptom of their lingering “traditionalism,” or—worse yet—a reflection of their position as pawns of a sinister contingent of rogue Western conservative religious activists. Throughout my fieldwork I was struck by this persistent assumption: that Ugandan Christian social activism is pursued under the guidance of American Christians and conservative politicians and that the beliefs and interests of these two groups—American and Ugandan—were interchangeable. One of the main purposes of this book is to elucidate the ways this was often not the case. My intent is to reveal and explain something about the motivations and moral orientations of Ugandan Christians, highlighting their own agency and agenda in the social protests (for abstinence as an AIDS prevention method, and against homosexual rights) that have come to define them in recent years.

The Book’s Structure, and an Outline of the Chapters

This book is structured as an ethnographic study of a policy in that it considers, to quote Catrin Evans and Helen Lambert, “how interventions enter into existing life worlds and both shape and are shaped by them.”58 It is divided into three sections that lead the reader from the historical and political context that gave rise to PEPFAR’s origins, to an analysis of its impact within one Ugandan community, to the long-term effects or “wakes” that have remained in the years following its initial implementation. Part 1 draws on archival research, analysis of U.S. congressional records, and interviews with key figures in Uganda’s health and religious sectors involved in early AIDS prevention efforts. Part 2 is the ethnographic heart of the book, where Ugandan responses to and interpretations of PEPFAR’s policy are analyzed. Part 3 is also primarily ethnographic, focusing on the broader social and political effects of the policy in Uganda, especially in terms of attitudes surrounding gender and sexuality, including homosexuality.

Part 1, which outlines the context for the PEPFAR program, begins with a focus on the history of the PEPFAR policy itself and its initial implementation in Uganda. Chapter 1 explores the meaning of the idea of compassion in American politics and how it came to refigure international aid under the Bush administration. It provides a historical overview of AIDS prevention policy in Uganda and analyzes the role that born-again Christian activists have played in AIDS policy since 2004 in Kampala. It also sheds light on the motivations of the American politicians who crafted the policy and stipulated the controversial limits on how prevention programs would be funded. Chapter 2 provides historical background for the current political and religious climate in Uganda, its purpose being to focus a historical lens on the role that Christian churches have played in political and social struggles in Uganda over the course of the last century. The AIDS epidemic has heightened a sense of social instability, and in its wake there has been a proliferation of discourses that assert a return to the moral certainty promised by “traditional” gender relations, generational obligations, and modes of spiritual and social authority. This chapter explores how these arguments have been formed in dialogue with a much longer history of debates over changing household dynamics, women’s roles in society, and the place of ethnicity within the nation-state. Here I develop more fully what role so-called moral authority has played in the Ugandan political sphere and how contemporary discussions of morality are shaped by a decades-long history of the “moral reform” of the home.

Part 2 comprises chapters 3–5, which examine the meaning and practice of abstinence and faithfulness within a community of Ugandan born-again Christians. These chapters highlight how this message was refigured within Uganda to address the particular moral and spiritual struggles that young people encountered. Chapter 3 is the first of two chapters to examine the message of abstinence. The chapter focuses on how abstinence was framed as a certain type of (Christian, neoliberal) moral message and the ways it was compared and contrasted with other forms of sexual education in Uganda that emphasized different types of moral subjecthood. It includes an examination of how youth made sense of and resolved the moral disjunctures that abstinence created, and how such negotiations both established the strategy’s appeal and demarcated its limitations as a public health approach. Chapter 4 focuses specifically on how abstinence was evaluated in terms of Ugandan frameworks for health and healing. It explores how abstinence was a practice driven by forms of spirituality and experiences of embodiment that diverged from Euro-American and biomedical orientations to health. I suggest that the ability to reframe abstinence in terms of these local orientations to spirituality and embodiment played a large part in how and why this became a popular health message within the Ugandan born-again community.

Chapter 5 examines the message of faithfulness as a prevention strategy and interprets how a message about planning for marriage was shaped by intergenerational conflicts in contemporary Kampala. I highlight especially how these conflicts played off young men’s feelings of marginalization in the contemporary economy and how a message about AIDS prevention that asked them to withdraw from sexual relationships—usually a key measure of status for young men in Kampala—could succeed when paired with other neotraditional messages about gender relations and marital and household dynamics.

Part 3 begins with chapter 6, which serves as a coda for my ethnography of the church community as it focuses on the years after the end of the first phase of PEPFAR funding—a period when activism within the church expanded beyond AIDS prevention to address a wider array of concerns over sexual behavior. During this period members of UHC emerged as key participants in the antihomosexuality movement in Uganda, a series of protests that culminated in 2009 with the introduction in parliament of a bill that would radically intensify criminal punishments for men and women identified as homosexuals. This chapter analyzes the controversy over Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill as part of the longer struggle to manage sexuality and gender relations in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries in Kampala.59 In particular, it considers ideas about sexual personhood and sexual rights in Uganda today, and some of the problems faced by international and local groups that seek to protect gay Ugandans by building on rights-based arguments for sexual equality. Chapter 6 provides a window on how social activism within the church has changed in light of changing relationships with American Christians and a somewhat transformed political climate in the United States. Exploring the implications of accountability within other humanitarian endeavors, this chapter contributes a discussion of how efforts to extend the platform of human rights to include sexual minorities in Uganda has engaged and broadened many of the moral dilemmas I articulate earlier in the book.

Finally, this book’s epilogue revisits the concept of accountability as a key framework for global health projects. In the years following the end of PEPFAR’s initial grant period (2003–8), when abstinence and faithfulness fell out of favor as a dominant prevention strategy adopted by the U.S. government, members of UHC reflected on their role in a global AIDS prevention project. Their sense of frustration at the changing priorities of foreign funders revealed some of the limitations of global health partnerships that supposedly emphasize individual empowerment and personal accountability without acknowledging the ways that cultural, moral, and structural factors contribute to a community’s experience of health and well-being.