Читать книгу Preaching Prevention - Lydia Boyd - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

AMERICAN COMPASSION AND THE POLITICS OF AIDS PREVENTION IN UGANDA

When President George W. Bush introduced the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) in his 2003 State of the Union address it was remarkable for many reasons, but most notable was the dramatic shift it represented in the U.S. government’s stance toward HIV/AIDS. It was not until 1986, a full five years after health officials began to track the spread of the epidemic in the United States, that President Ronald Reagan publicly uttered the term AIDS for the first time.1 His long silence, a veritable erasure of the epidemic from official concerns during his first term in office, reflected a broader attitude of fear and indifference that permeated the Reagan administration’s response to the rapidly unfolding health crisis.2 Federal financing for AIDS-related research was also severely limited early on, in large part because of the opposition of prominent conservative politicians in Congress. Senator Jesse Helms, one of the most vocal of these opponents, gained notoriety for his declarations that the disease was the result of “deliberate, disgusting” conduct and thus was undeserving of scientific attention.3 In the 1995 congressional debate over the reauthorization of the 1990 Ryan White Act, one of the first American policies that sought to secure care and treatment for Americans living with HIV/AIDS, Helms argued against refunding it. He told a reporter for the New York Times that “we’ve got to have some common sense about a disease transmitted by people deliberately engaging in unnatural acts.”4 Helms and his peers espoused the view that those who were dying of AIDS had behaved irresponsibly, even sinfully, and that these moral indiscretions made them accountable for their pain.

Given this, it is striking that less than a decade later President Bush, himself a conservative Republican, announced a global program to combat HIV/AIDS that is considered by many to be one of the largest and most important public health policies ever deployed. In his 2003 State of the Union address, Bush movingly argued that government policies are, at their best, vehicles for the personal compassion and care that Americans demonstrate to those in need everyday. Describing South African AIDS patients dying without access to treatment, Bush argued that PEPFAR represented a “work of mercy” capable of transforming the lives of millions suffering around the world.5 With the stroke of his pen, AIDS moved from the margins to the forefront of U.S. health and global agendas. Even more remarkably, the AIDS patient was transfigured from the deserving sinner of 1980s urban America to the suffering victim (often in Africa, and often a woman) whose image seems so irrevocably linked to the epidemic today. What had precipitated this apparent about-face in how American conservatives viewed HIV/AIDS?

This question shadowed the early stage of my research in Uganda. In interviews I conducted in July 2004 with American and Canadian missionaries living in Kampala, the impact of PEPFAR was already evident. Members of Christian organizations that until that year had had limited involvement in HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention programs spoke to me in moving terms about their plans to become engaged with the issue and seek PEPFAR funds.6 One middle-aged Canadian man told me how he had recently been “called” to the issue of HIV/AIDS and was expanding his mission’s programs to address the epidemic. But the embrace of the issue was not without some conflict. Another missionary, someone who had dedicated most of his adult life to Ugandan relief work, confessed that until that year he had been little involved in AIDS programming, in large part because the U.S. churches that supported his work did not consider the issue to be central to a Christian mission like his. He explained that because HIV/AIDS was associated with “immoral behavior” it was difficult to find funding from religious American donors for such programs. Another missionary couple, who coordinated an AIDS education program funded by USAID, told me that they had prayed for a year, seeking to overcome their conflicting feelings about AIDS, before taking on the project. These views were not particularly uncommon. As Christine Gardner recounts in her study of U.S. sexual abstinence programs, a donor survey conducted in 2000 by the international Christian nongovernmental organization World Vision—just three years before Bush introduced PEPFAR—revealed widespread resistance among Christians to funding HIV/AIDS programs in Africa—even those serving orphaned children. One problem that World Vision leaders identified was the perception that AIDS sufferers “deserved their fate.”7

For many of the Christian aid workers I spoke with that summer, the ground shift that precipitated their involvement in AIDS programming was related to changes in the ways AIDS patients themselves were perceived. No longer viewed as victims of their own misguided behavior, people suffering from AIDS—especially in places like Uganda—were seen as deserving candidates for compassionate intervention and aid. The introduction of PEPFAR, with its stipulations reserving a percentage of prevention funding for “behavior change” programs, bolstered the perception that AIDS prevention work could be a platform for social transformation and moral intervention. Moreover, Bush’s faith-based policy initiative, which he had introduced in 2001, allowed for the broader engagement and direct federal funding of religious organizations in both domestic and foreign humanitarian and development work.8 The couple above who were in the process of implementing their AIDS education program pointed to the faith-based policy as the reason they had taken on that project. The woman told me that “the U.S. [federal government] would fund our programs in the past—relief work and the like—but this AIDS curriculum development program? No way.” Her implication was that the federal government had long considered most nonemergency humanitarian work done by missionaries to be outside the legal parameters of federal funding guidelines, which prohibit the support of projects that have a primary focus on religious proselytizing.9 But now, under President Bush, religious and community organizations had been broadly encouraged to compete for federal funding and to occupy a more central role in the administration of a wide range of social services. On the ground in 2004 it seemed that PEPFAR and related U.S. federal policies were transforming the ways North American religious organizations considered the scope and impact of charitable and humanitarian intervention in Uganda.

In this chapter, I trace the significance of these shifts in attitude and engagement by considering the emergence and effects of an ethic of compassion within U.S. political discourse, an ethic that under President Bush’s leadership came to shape how and why social welfare and international aid programs—and especially AIDS prevention programs—were pursued. My focus on compassion is an effort to analyze the underlying rationales that gave rise to PEPFAR in the early years of the twenty-first century, as well as the effects—intended and unintended—that followed the policy’s implementation. My primary focus in the first half of this chapter is on American moral sentiments and ambitions: what drove American contributions to HIV/AIDS relief and prevention in Africa, and what forms did such contributions take? My second aim is to explore the immediate effects of American compassion on the tenor of AIDS activism and on the landscape of AIDS prevention in Uganda. How was the American approach different from others that had—famously and successfully—preceded it? And, perhaps more significantly, what forms of social action and approaches to health and wellness did American compassion, with its ensuing emphasis on personal accountability, help generate?

America’s Armies of Compassion: Making the Accountable Subject

President Bush’s decision to address the global HIV/AIDS epidemic grew out of his efforts to develop what is now widely described as his “compassionate conservative” approach to governance. In the 2003 State of the Union address, Bush explained why he believed compassion should play a fundamental role in government policy. “Our fourth goal,” he noted, “is to apply the compassion of America to the deepest problems of America. For so many in our country—the homeless, and the fatherless, the addicted—the need is great. Yet there is power—wonder-working power—in the goodness and idealism and faith of the American people. Americans are doing the work of compassion every day: visiting prisoners, providing shelter for battered women, bringing companionship to lonely seniors. These good works deserve our praise, they deserve our personal support and, when appropriate, they deserve the assistance of the federal government.”10 In the context of a federal policy speech, “compassion” invokes an ideal of the benevolent state, a government that identifies need and suffering and acts to address it. Yet Bush’s compassionate conservativism sees compassion not as a value that the state itself possesses but one provided by its citizens.11 It is a policy goal that seeks to pave the way for the empowerment of the private sector and private individuals who may address need and show compassion in their everyday lives, theoretically reviving a sense of civic responsibility and restoring the balance of moral governance in American society. Bush famously referred to charities and religious groups as “armies of compassion,” better equipped than the state to address social problems like homelessness and poverty.12 This was a compassion effected through the nurturing of a relationship not between the state and its needy citizens but between the state and a private sector sanctioned to serve the needy—battered women and lonely seniors—in ways believed to be more efficient and effective than those undertaken by the government itself.

This shift underscores how Bush’s interpretation of compassion was marked by a broader inflection of neoliberal principles in his approach to governance and international aid. In the wake of 1990s domestic welfare reforms, individuals and the private sector were encouraged to participate in work previously relegated to the state and in turn were made more responsible for their own and their community’s well-being.13 The state’s role in social programs was criticized by conservative backers of such reforms as inefficient, lumbering, and part of a legacy of progressive Democratic approaches to the problems of poverty that had supposedly created a relationship of dependency, rather than accountability, between citizens and the state. In the 1990s public policy rhetoric in the United States increasingly emphasized qualities like personal empowerment, self-esteem, and individual responsibility as the end products of a new free-market-dominated system characterized by looser labor regulations and a global corporate system hinged to a post-Fordist strategy of “flexible capital accumulation.”14 In the wake of these reforms, Bush’s “compassionate” turn injected the image of the caring state back into the public consciousness. Yet the language of compassion, like these earlier policy endeavors, transferred the onus and responsibility of social services onto the citizen-volunteer, who was emboldened to take charge of social problems in lieu of state services.

The rise of a volunteerism as an expression of civic duty and as a key element of the transformation of the late capitalist state has been well documented.15 President George H. W. Bush’s famous “thousand points of light” speech, made at the 1988 Republican National Convention, presaged the celebration of volunteerism as an essential aspect of new forms of citizenship and social action that would come later. The Big Society program of British prime minister David Cameron provides a more contemporary corollary for how volunteer organizations have been heralded as essential tools through which society may compensate for the reduction of social welfare programs. Andrea Muehlebach’s analysis of an emergent “moral” form of citizenship at the heart of the northern Italian neoliberal state has highlighted some of the key contradictions behind these trends;16 her study of voluntarism in and around Milan from 2003 to 2005 notes how the heightened political emphasis placed on volunteer organizations during this period was driven by the desire to create a new “species of citizen” whose unpaid charitable productivity would fill the gaps created by a retreating postwelfare state.17 Yet, contrary to a purely critical analysis, Muehlebach argues that the effect of this trend has been to complicate depictions of the neoliberal state as purely a rationalizing, amoral project. Similar to American conservative discourse, Italian reformers emphasize the emotional social bonds that are enhanced through volunteer labor; citizens are encouraged in Milan to “live with the heart,” the message being that personal sentiment may animate state policy and make it more effective.18 In this way the rise of volunteerism in Italy has been embraced by formerly critical sectors of society—such as the Communist Party and labor unions—for the ways in which such reforms are believed to generate new forms of “solidarity.”

A notable aspect of this shift from state welfare to volunteer labor in both Italy and the United States is the way that services once considered to be the right of citizenship are encountered in this new version as a privilege, a “gift”—albeit ideally an emotionally resonate one, the product of a fraternal sentiment between citizen-donor and recipient. Marcel Mauss, in the conclusion to his famous essay on the gift, highlights connections between the emergent welfare state in early twentieth-century France and the reciprocal moral obligations that he views as emblematic of gift exchange.19 In his idealized description, the interconnections among labor unions, workers, employers, and the state create a web of obligations that ensures security and solidarity for all. But in its late twentieth-century iterations the “gift” of compassion becomes both highly personalized and one-directional. The emphasis on volunteerism reimagines the gift of social services as unrequited, a demonstration of care in the face of abject need, seemingly given without expectation of compensation or reward. As much as the language of compassion sought to empower and mobilize American and European volunteers, it also undermined the agency of those who received aid. The needy were not partners in such works of compassion, viewed as members of a broader interdependent society, but instead were characterized as recipients of their neighbors’ benevolence and care. The “right” to health care, safe housing, and food is reinterpreted in conservative language as a problem of “entitlements,” a system that emphasizes the dependency, rather than the productivity, of the poor.

The context of international aid shifts the dynamic of the relationship of citizen and state to one of donor and recipient, but many of the effects of this rhetorical turn remain. The idea of compassion may be contextualized as part of the broader emergence in recent years of a “politics of care” that has shaped contemporary responses to humanitarian crises worldwide.20 Erica James describes the “political economy of trauma” in Haiti as a “compassion economy,” one that “can transform pain and suffering into something productive.”21 As Miriam Ticktin points out in her study of French asylum policies, the emergence of care as a platform for governance has shaped the subjects of the state’s concern in particular ways.22 The compassionate response is provoked by images of suffering, the recognition of a “morally legitimate” subject whose abject physical need compels our action. Drawing on Michel Foucault’s notion of “biopower,” a term he coined to explain the mechanisms through which life becomes the object of the state’s “explicit calculation,” Ticktin, James, and others have highlighted how the suffering body has emerged in recent years as the dominant platform upon which claims to state and nonstate resources may be made—a platform that has in many instances displaced and closed off other possibilities for collective political action.23 This trend has perhaps been nowhere more evident than in the realm of international AIDS relief, where the ability to convey abject suffering to nongovernmental agents with the power to provide access to scarce medical resources may mean the difference between life and death.24

This recent work has brought about a question: When care or compassion becomes the central focus of international governance, what forms of subjectivity and political advocacy gain leverage? In the wake of policy reforms like PEPFAR, which infused major American global aid programs with the ethic of compassion and mercy, this question took a new shape: What kinds of “healthy” subjects and behaviors were made recognizable by the language of compassion, and why? Moreover, what effect did an emphasis on compassion have on long-standing and successful local efforts to prevent the spread of HIV in Uganda?

For President Bush and his advisers, the compassionate response was driven not only by the recognition of the suffering of others but also by the effect compassion itself was believed to engender. Bush described the compassionate approach as “outcome based, driven by results” and called for “compassionate results, not compassionate intentions.”25 He wrote in his administration’s Armies of Compassion policy overview that “government should help the needy achieve independence and personal responsibility.”26 Compassion was viewed as a gift of redemption, a personal sentiment that when deployed enabled the social transformation of needy communities and individuals into accountable, responsible—but not “entitled”—persons.

These ideas were informed not only by a neoliberal orientation to governance but also by a distinctly Christian understanding of the nature of compassionate sentiment. For American Christians, Bush’s language resonated strongly with familiar lessons about charity and the transformational effects of what evangelical Christians call the “selfless love” that characterizes demonstrations of mercy for the poor and suffering. Evangelical and born-again Christians believe that compassion “invokes an ideal of empathetic, unconditional benevolence,”27 the demonstration of care in a context in which it may be least expected. Compassionate acts are selfless gifts but, perhaps paradoxically, they also engender an expectation of evidence of the transformational power of God’s love. As Omri Elisha has discussed in his study of American evangelicals in Tennessee, charitable compassion is dialectically linked to an ideal of “accountability,” the expectation that recipients of care demonstrate or reflect godly virtue.28 The gift of compassion is on the surface understood as an act of selfless mercy, but it is also a gift capable of radical change, affecting personal conduct and, by extension, the moral fabric of society. In the eyes of conservative Christians at the turn of the twenty-first century, domestic welfare programs were redeemed by their transformation into programs of individual and community charity that were driven by the personal sentiment of compassion. Compassion in this American context was believed to address the problems of state welfare not only because the state became more efficient but because compassion combined care with the unstated expectation of personal change among recipients. A sense of empathy generated such Christian compassion, as did the possibilities for self-transformation that such a worldly (and spiritual) gift was thought to enable. By applying compassion to his global political agenda Bush signaled a similar emphasis on the transformational power of humanitarian mercy.

The idea that compassion was a transformational gift, one that engendered accountability in needy recipients, was a powerful tool in enabling the American conservative embrace of AIDS relief work, and for Bush’s evangelical base this idea suddenly brought popularity to AIDS as a cause. Compassion was a sentiment driven not only by moral obligation but also by the “moral ambitions” for social change that extended from American ideals of volunteer and humanitarian work.29 This was an orientation to charity and donor aid that was shaped in particular by evangelical Christian notions of what a demonstration of compassion meant and what response it should invoke. As I noted above, compassion in this instance was embedded not only in an idea of ethical obligation to those suffering but also in the notion of the work God’s love does for and on the suffering subject. In American endeavors to show mercy, there was a parallel expectation that subjects would become accountable and empowered in return.

The language of compassion placed the onus on recipients of aid to demonstrate the transformational effects of their care. In the case of PEPFAR, such demonstrations were closely linked to an expectation that disease risk could be self-managed. If subjects of aid became more accountable for their behavior, especially by exhibiting better self-control, the forward march of the AIDS epidemic could be stalled. The years preceding and following PEPFAR’s introduction in 2004 saw the growing influence of the language of “behavior change,” an exhortation that encompassed a number of conduct-related prevention strategies. It became a popular concept for the Bush administration because of the ways it seemed to reinforce the sentiment behind the shift toward compassionate accountability as a key aspect of governance. Behavior change was celebrated as a strategy that emphasized individuals’ own power to control their exposure to disease risk; if they could change when and with whom they had sex, and if young people could delay sexual debuts, AIDS could, in theory, be prevented.

For the remainder of this chapter I turn to the debates that surrounded PEPFAR’s initial funding by the U.S. Congress in 2003 and the introduction of it in 2004, tracing the emergence of behavior change as a comprehensive prevention strategy and the contested meanings attributed to the term. Of particular interest are the ways in which compassion and behavior change transformed how Ugandans addressed and responded to AIDS. By 2004, when PEPFAR was implemented, individual actors, rather than communities, were made responsible for managing their own AIDS risk. As I will discuss, this precipitated a remarkable shift in the shape of Ugandan small-scale grassroots activism. I turn first to the global context and to the debates surrounding the funding for AIDS prevention and treatment that preceded PEPFAR’s introduction.

PEPFAR, and Global Response

At the 2004 International AIDS Conference in Bangkok, Thailand, President Bush’s proposal to spend $15 billion on global AIDS programs garnered widespread attention; the program’s scope was radical by any interpretation. As recently as 2001 Peter Piot, the executive director of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), had confronted the United Nations’ special session on HIV/AIDS with dire statistics outlining the extent of the global epidemic and the anemic response that donor nations had demonstrated to date. Piot spoke of the “collective shame” that marked inaction on the part of the world’s wealthy nations and their responsibility to the dying in poorer ones.30 That year international attention had focused on the expansion of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, which UN secretary-general Kofi Annan publically supported with his own personal pledge of $100,000. The Bush administration responded with a pledge of $200 million to the fund, with the stipulation that the UN project focus attention on prevention of HIV infection rather than treatment of AIDS.31

Global access to treatment had been a controversial issue at the International AIDS Conference held in 2000 in Durban, South Africa. Beginning in 1995, multidrug treatment with antiretrovirals had been shown to adequately control the replication of the HIV virus in patients. Antiretroviral (ARV) therapy had radically altered AIDS treatment in the West, transforming the virus into a chronic health problem rather than a death sentence, but treatment was expensive and complicated, demanding regular medical supervision to manage the high occurrence of side effects and the ever-present risk of developing resistance to some or all of the first-line treatment drugs. Detractors asserted that it was simply too complicated and too costly to provide treatment to the millions of HIV-positive persons living in resource-poor countries; activists countered that poor people were wrongly perceived as unable to follow the complex regime that ARV treatment demanded. Others lambasted the pharmaceutical industry for resisting the inexpensive reproduction of ARV drugs in generic form, a tactic that had been adopted by Indian drug companies and successfully used by the Brazilian government to facilitate its national treatment program, which had begun in 1996.32 Limited access to treatment in the late 1990s and early years of the twenty-first century created a dire landscape of AIDS care, with those living in Western nations mostly assured of a life living with AIDS and those in poorer countries condemned to death. Miriam Ticktin’s study of French immigration policies and Vinh Kim Nguyen’s study of HIV treatment clinics in West Africa during this period describe the effects of such stark inequalities.33 Access to treatment—either through international migration or through a petition to receive the limited aid of a donor agency—necessitated a triage approach to care in which the scarcity of resources demanded that health care workers evaluate need and suffering and decide on those most deserving of help.

It was into this environment that President Bush introduced PEPFAR. In contrast to a scenario of limited resources, of UN officials chiding donor countries to make donations for AIDS relief in the hundreds of millions of dollars, PEPFAR represented an infusion of cash of unprecedented proportions, with the vast majority of that money earmarked for treatment. The initial program pledge of $15 billion was to be divided between fifteen nations identified by the Bush administration as most affected by the epidemic, a list that included Uganda and was heavily focused on nations in sub-Saharan Africa.34 Four-fifths of the money was directed toward treatment, a sum that immediately transformed debates over ARV access. To give some sense of the size and scope of the initial program, in fiscal year 2002—the year before PEPFAR was initiated—the U.S. government spent a total of $287 million on AIDS relief in Africa. By fiscal year 2006 that budget (including funding from PEPFAR) had expanded to nearly $1.3 billion, a nearly fivefold increase.35 PEPFAR has dramatically expanded funding for both treatment and prevention in Uganda; for fiscal year 2008, the program accounted for $283 million of the $388 million in Uganda’s budget for AIDS prevention and treatment and provided more than 70 percent of the country’s entire resources for HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention, far outpacing the contributions of the Ugandan government and the UN Global Fund, Uganda’s second biggest contributor to HIV/AIDS programs.36 By all accounts PEPFAR is a program that has redefined HIV/AIDS treatment and care worldwide.

Despite these transformational numbers, PEPFAR was not wholeheartedly embraced by the global AIDS care community. As was noted in this book’s introduction, the most controversial aspect of PEPFAR was that the program reserved one-third of its prevention funding ($1 billion) for abstinence and faithfulness-only programs.37 At the 2004 International AIDS Conference in Bangkok the structure of PEPFAR’s prevention funding drew intense criticism. An editorial in the Lancet described the tense reception at the conference of President Bush’s Global AIDS coordinator, Randall Tobias: “Tobias was distinctly ill at ease and, for a few moments as he left the podium under strong verbal attack, it appeared that he would withdraw from the lecture.”38 Criticism extended from questions about the president’s motives and especially the clear focus that Bush and the program’s terms had placed on the role of religion in the fight against AIDS.39 The Lancet editorial recounts Bush’s speech, in which he touted an ABC approach (abstain, be faithful, and—adding the qualification “when appropriate”—use condoms) as a “moral message” and placed special emphasis on the importance of youth abstinence as an approach that prevents HIV “every time.”40 Many in the world of AIDS prevention distrusted the focus on abstinence, especially as it sought to drive funding away from other programs (in particular, those of condom distribution) that were perceived as less aligned with the Bush administration’s social agenda.41

A Ugandan Christian activist I knew recalled for me his experience at the 2004 Bangkok conference, where he participated in a panel that seemed to dramatize the tensions of the moment. He was only in his early twenties at the time, and this trip—which took him halfway around the world—was the first time he had ever been on an airplane or traveled outside eastern Africa. At the time he was, he admits, unfamiliar with the landscape of international AIDS activism; his experience with AIDS advocacy extended only to his role as youth leader at University Hill Church (UHC), a congregation near Makerere University in Kampala that advocated premarital sexual abstinence. He had been selected as a youth representative for Uganda at the conference and was slated to appear on a panel discussing the role of abstinence programs in HIV prevention. He described to me his initial realization that controversy surrounded HIV prevention methods, especially abstinence:

At that point I wish I knew better. I was in my final year at the university. It was an international AIDS conference. I was in Bangkok, in Thailand. It was my first opportunity to fly. It was really great. One of the greatest things, as a leader, is your story of transformation. So I had my story, you know. This is what had happened, this is what changed . . . I made the decision to abstain, and I’m just living my life and going on. And so I go over and I was simply supposed to give my testimony. And some guys were like, “Abstinence is an illusion, it doesn’t happen.” The guy who spoke before me, Dr. Steven Sinding [who represented] Planned Parenthood,42 and then a girl from India. And I was like, “Guys, am I an illusion? I made a decision to wait! And I’ve been waiting, and it helped me!” So this was really eye-opening for me. There were four people presenting, but 80 percent of the questions came to me. But I kept the story. Some guys came and said, “Thank you very much for sharing the story.” Then I talked to [prominent American evangelical minister] Rick Warren’s son, shared with him some personal things, kept him in prayer, and then we kind of kept in touch.

Andrew had been prepared to “testify” in a mode of speaking common to evangelical and born-again Christians the world over. Testimonies are narratives of personal transformation shepherded by faith. In Andrew’s eyes his faith had helped him abstain from sex, which had enabled his transformation from a sinful youth to a principled young man. For him this was a positive story, one laced with allusions to his own aspirations and personal achievements: nearing completion of his college degree and planning for marriage. This was a message central to the teachings in Andrew’s church—that abstinence could be a strategy of upward mobility and social achievement—and it was one now being sanctioned by the U.S. government. Andrew and his peers’ experience with abstinence is a topic I will return to at length in later chapters, but the story he tells here is about the controversy that surrounded abstinence, and the sense of division within the world of AIDS activism that PEPFAR had seemed to generate. Andrew had been dropped into a struggle over public health policy that was animated by a broader conflict rooted in the U.S. religious and political landscape. In Bangkok, the first major international AIDS conference following PEPFAR’s introduction, an American conservative coalition had, to an uncertain reception, thrust itself into the world of AIDS research and programming. Andrew’s offhand mention of Rick Warren highlights the way in which PEPFAR and abstinence had emerged as a key arena for this American struggle, and the ways in which American politics and American religion had come to have an impact in even seemingly remote African communities. In fact, these African communities were placed at the very center of these debates.

Harnessing the Story of Uganda’s Success: Defining Behavior Change

It was also at the Bangkok conference that the Ugandan story of declining HIV prevalence rates took center stage, in large part because the Bush administration had cited the country as evidence for why abstinence and faithfulness-only programs had been earmarked for special funding. Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni was a featured speaker at the conference, and he delivered a wholesale celebration of individual responsibility and self-control as frontline defenses against the epidemic:

Eighteen years ago, as we emerged from a two decades protracted peoples’ war of liberation against the dictatorial regimes of [Idi] Amin and [Milton] Obote, Uganda was once again under the shroud of a devastating mysterious ailment called “Slim,” later to be known as AIDS. Two decades of civil war, state mismanagement and inappropriate monetary policies had left the Ugandan economy and social infrastructure in tatters with extreme levels of household poverty. The medical infrastructure, especially the hospitals, were in a sorry state with many of the medical profession living in exile, and the total per capita expenditure on health at less than $1 per annum. By 1985, Uganda was among the ten poorest countries in the world.

We had to transmit to our people the conviction that behavior change and therefore control of the epidemic was an individual responsibility and a patriotic duty and within their individual means. In our fighting corner was a resilient population and a committed leadership with years of fire-tested experience in mobilizing our people to overcome obstacles at great odds and with minimal resources.

Our only weapon at the time [was] the message: “Abstain from sex or delay having sex if you are young and not married, Be faithful to your sexual partner (zero grazing), after testing, or use a Condom properly and consistently if you are going to move around. This has now been globally popularized as the ABC strategy.” With no medical vaccine in sight, behavioral change had to be our social vaccine and this was within our modest means.43

By the late 1990s, HIV/AIDS had become increasingly important to Museveni’s profile on the international scene, bolstering his image as a “new African statesman” intent on supporting political reforms and terms for economic growth that were supported by his allies in the West. Uganda’s government, like others across Africa, had become heavily dependent on foreign donor aid during the 1980s and 1990s; by necessity Museveni had embraced economic restructuring in 1987, opening Uganda to international donors who had avoided the country under the Amin dictatorship of the 1970s, a period that had been characterized by intense xenophobia and economic isolation in Uganda. While Museveni had come to power in the mid-1980s as a leader espousing “revolutionary” politics with an antielitist and broadly socialist ideology of rural uplift, by the 1990s the locus of his power was clearly situated in and through the economic and political relationships he fostered with the West.44 The state’s reliance on international aid expanded significantly during the first two decades of his rule.45 And, as was the case in other parts of the world during this period, there were changes in the manner in which that aid was distributed. The aid world had become radically decentralized during the 1980s and 1990s, with direct state-to-state aid becoming a less popular model for donors.46 Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and faith-based organizations emerged as critical players in the local management of donor funds.47 These trends redefined the landscape of AIDS care and treatment in Uganda, a sector that has seen the expansion of medical research projects fueled by donor funds.

Museveni’s speech in Bangkok highlights many of these trends, especially in the way he links economic restructuring to a successful HIV prevention strategy he calls “behavioral change.” In the years just prior to the Bangkok conference, behavior change emerged as a popular term highlighting individual accountability in health care choices. In Museveni’s speech, avoiding disease risk by delaying sex and by promising faithfulness within monogamous relationships were celebrated as choices that buttressed other economic and political changes in Uganda. As Ugandans became more accountable, empowered, and self-reliant citizens, their nation supposedly also became more economically viable, more democratic, and better able to manage the epidemic that had ravaged its populace. In Museveni’s words, control of the epidemic was an “individual responsibility” and within “individual means.”

In fact, this language of self-sufficiency in many ways obscured the heavily community-based approach that Ugandans had embraced in the early years of the epidemic—strategies that emphasized accountability not only to one’s self but to others, including those infected and at risk. Early prevention education emphasized peer-to-peer counseling rather than any top-down centralized curricula. Women’s groups, newly empowered in the early years of the Museveni government, had organized themselves to address the impact of the epidemic on communities and families. But in a global context that emphasized neoliberal structural reforms, behavior change came to stand for liberal democratic ideals steeped in the rational, autonomous individual. One Ugandan public health student I interviewed in 2010 succinctly characterized the shifts from the 1980s to early years of the twenty-first century in Uganda when she said, “In the eighties there was a sense of communal vigilance [about HIV]. Communities became vigilant and aware of each other. It is not the case anymore. It is more about individual aid. [Prevention], now it’s your call.” By Museveni’s calculation, behavior change seemed to represent these broader shifts in global sources of power and influence as well as the changing Ugandan economic and political context that marked early twenty-first-century life. Behavior change was a “technology of citizenship,” to use Barbara Cruikshank’s term, a mode of governance that has proliferated in the neoliberal era and “work[s] on and through the capacities of citizens to act on their own.”48

What is most remarkable about the global adoption of behavior change is the way it came to replace earlier Ugandan strategies that focused more on community transformation than individual accountability. Long before there was widespread international focus on AIDS in Africa, Ugandans had in fact changed their behavior in ways that helped reduce HIV, but by the years of the new century the term behavior change had come to stand for something more particular than changing when and with whom one had sex. Perhaps more troublingly it was a term that obscured the broader structural shifts within Ugandan society that had made “changing behaviors” more feasible for many.

Uganda’s “Miracle,” and Sociostructural Components of Prevention

Rapid political changes emphasizing democratic participation and the increasing leverage of women and youth in local politics provided the critical backdrop to HIV programs of the 1980s and 1990s in Uganda. Contrary to his later incarnation as a Western-friendly advocate of open-market reforms, Museveni’s early politics were influenced by his training at the University of Dar es Salaam in the late 1960s, a period defined by the expansion of Tanzanian president Julius Nyerere’s Ujamma (African socialist) reforms. In publications during his first decade in power Museveni voiced an idealistic desire to politically mobilize the peasant classes in Uganda, and his early policies emphasized reforms of local government structures to encourage broad-based participation.49 He has recently come under strong criticism for his long-held resistance to multiparty democracy (only retracted before the 2006 elections) and his iron grip on political leadership in Uganda,50 but when he came to power in 1986 he was widely viewed as a political reformer who championed democratic governance and resisted corruption. The party leadership of Museveni’s National Resistance Movement (NRM) opposed discrimination based on gender, age, education, and ethnicity.51 Women and youth, traditionally groups with limited political influence, were given special consideration in electoral politics. Women’s and youth seats were reserved at all levels of government, and in the first years of NRM rule women were far more successful in their campaigns for open parliamentary seats than they had ever been before.52 Girls’ enrollment in school also increased during this period, and the new Ugandan constitution, ratified in 1994, strengthened women’s property and divorce rights.53 The position of women significantly improved in the 1980s, and they responded to these opportunities by becoming more involved and organized at all levels of society. During this same period Ugandan villages became politically revitalized and a culture of local organizing to address community issues—encouraged by the NRM’s grassroots politics—blossomed. Museveni’s government also held a privileged position during these years, buoyed by widespread trust and optimism—both domestically and in the global sphere—for the possibilities of political change and the genuineness and transparency of government leadership.

It was in this context that initial efforts to address the impact of HIV/AIDS emerged. Small rural communities in Uganda were faced with an almost unimaginably devastating epidemic in the 1980s, and the response within these communities was almost surely far more personal, small-scale, and community-centric than later efforts would be. The government and community messages surrounding HIV during this period were also clearly shaped by and responsive to local sexual attitudes. Museveni’s famous “zero grazing” phrase, adopted by Bush administration officials as an example of a Ugandan message promoting abstinence, referred not directly to sexual abstinence but to a mere reduction in the number of sexual partners.54 A comprehensive survey of Uganda’s prevention efforts in the 1980s and early 1990s emphasized that no single behavioral shift can be credited with drops in HIV incidence during this period.55 In a country where multiple concurrent partners are common, and where men view the support of multiple partners as a sign of their virility and status, many researchers argue that a message of no sex, particularly when levied at adults, would have fared poorly in these early years. Robert Thornton, an anthropologist who has studied Uganda’s prevention success, quotes an army officer as saying, “Thank God, Museveni never told us not to have sex! He would have been laughed out of the country!”56

Ugandan organizations founded during the first decade of the epidemic, such as The AIDS Support Organisation (TASO) (which early on emphasized the social cost of the epidemic on women) and the youth education group Straight Talk Uganda were highly effective in using peers to educate about HIV/AIDS, encouraging open discussion of a previously taboo subject and disseminating information in a culturally sensitive manner. Peer-to-peer education has been shown to be particularly effective in making disease risk a personal matter and creating a stronger sense of social pressure to adhere to behavior changes.57 Tellingly, Ugandans are more likely than any other Africans to have received information about HIV/AIDS from peers, as well as to have known someone personally living with the disease.58

In the 1980s and 1990s people in Uganda changed their behavior, delaying sexual debut and reducing their number of sexual partners. But such changes in behavior were also supported by significant structural shifts that had encouraged women and youth to take more active social and political roles in the country.59 Moreover, the government supported an integrated, multisectoral approach to prevention that did not privilege any singular message or policy.60 AIDS was a very real crisis; communities and the Museveni government responded by attempting to mobilize people against the disease, to talk about it candidly, and to use multiple approaches toward education and building awareness. Uganda’s success was dependent on the individual actions of people who followed the ABC (abstain, be faithful, use condoms) message that became famous by the end of the 1990s, but such individual decisions depended in turn on a broader set of social and structural changes that involved communities in the response to the epidemic, worked to reduce the stigma of living with and speaking about AIDS, and encouraged women and youth to organize and address the different ways in which the epidemic affected certain groups.61

By the year 2000, the broader set of structural changes that had accompanied HIV prevention success were overshadowed by a narrowed focus on individual accountability and self-control as primary tactics of disease management. Behavior change reflected the rhetoric of the neoliberal reforms of this new era, privileging values like autonomy and self-sufficiency. Yet as I have briefly outlined here, a drive toward self-control had not always been the dominant message regarding HIV/AIDS in Uganda. As the nation’s success circulated to the global level in the late 1990s, the story of its precipitous drop in HIV prevalence was applied as support for a broader U.S. political agenda that sought to emphasize the correlation between compassionate aid and the redemptive possibilities of personal accountability. Thornton recounts how USAID officials who had sponsored his research in an effort to prove that behavior change was the root of Uganda’s success became dissatisfied when his work argued instead that abstinence had not been a key component of Uganda’s early program.62 By 2003, when PEPFAR was introduced, the narrative of Uganda’s success had become contested terrain as various stakeholders sought to redefine why and how behaviors changed. This was nowhere more apparent than in the discussions that surrounded the initial funding of PEPFAR.

Ugandan Behaviors and U.S. Congressional Debates over PEPFAR

During the U.S. congressional debates that preceded PEPFAR’s funding, Uganda’s prevention strategy and the reasons for its success were strongly contested along political lines, with Republican lawmakers and Bush administration officials emphasizing the importance of abstinence and marital faithfulness to Uganda’s ABC strategy and Democratic lawmakers resisting this characterization of Uganda’s success. Testimony before the Senate and House subcommittees charged with addressing the new initiative demonstrated how Ugandan prevention policies were refracted through U.S. political and cultural divisions, leading to the program stipulations outlined in the 2003 legislation that funded PEPFAR. In one of the first of these meetings Representative Lois Capps, a Democrat from California, and Shepherd Smith, an American missionary with ties to the Bush administration, each framed Uganda’s success quite differently.63 Capps emphasized the integrated approach of Uganda’s program and noted that abstinence alone had not been effective in Uganda, noting, “Reports from USAID and U.N. AIDS indicates [sic] that comprehensive and community-based approach to HIV/AIDS prevention works best. The fundamental goal of these public health interventions is to change behavior and it appears that Uganda’s use of integrated behavioral change programs has had remarkable success. There is also no evidence that abstinence works alone. There is no data that sufficiently reports abstinence only rhetoric as causally decreasing rates of HIV/AIDS in Africa.”64 Smith—who, with his wife Anita, had founded a Christian NGO in Uganda—directly responded to Capps’s comments, challenging her emphasis on an “integrated behavioral change” strategy: “I think that it’s important to remember that this isn’t ABC in the context that we think of comprehensive sex here in America. It’s very targeted. It’s abstinence to kids. It’s be faithful to those in marriage or in monogamous relationships and it is [condoms] to very targeted communities such as the bars and the prostitutes and so on. So it is ABC, but it’s not all lumped together. It’s very segmented, [myself] having been there and looked at it very carefully.”65 In the years before PEPFAR, Ugandan AIDS programs were to a certain extent targeted toward certain populations and goals; many of these programs were developed and coordinated at local levels to address particular community concerns. But the sort of fracturing and policing of boundaries that Smith mentioned only became evident in the wake of PEPFAR’s implementation; for example, it was in 2004 that Museveni removed any mention of condoms from school sex-education curricula.66 As I discuss in the following section, in the wake of PEPFAR, U.S. efforts to categorize programs in order to evaluate them for funding established a new emphasis on the boundaries between distinct program areas, such as “condoms and related activities” and “abstinence/be faithful.”67 Smith’s statements foreshadowed, rather than reflected, what was to become a much more fractured approach to AIDS care in Uganda.

Representatives of the Bush administration brought up Ugandan “culture” as justification for the abstinence and faithfulness focus of PEPFAR, often in surprising ways. Dr. Anne Peterson, the director for global health at USAID in 2003 and, by her own account, a former “missionary doctor in Africa,” noted in testimony that “being faithful [to one partner] is a strong cultural norm that resonated strongly in Uganda and, from my own experience, I know it resonates also in many other African countries.”68 Many Ugandans would question this evaluation of Ugandan cultural norms or at least seek clarification of what “faithfulness” meant in the context of Peterson’s speech. Long-term concurrent sexual partnerships (maintaining more than one regular sexual partner at one time) have in fact figured prominently in epidemiological explanations for Uganda’s high HIV prevalence rates.69 Peterson’s comment also downplays the important distinction between Uganda’s locally developed programs—the most famous of which, “zero grazing,” targeted a reduction in the number of sexual partners—and PEPFAR’s faithfulness message. The terms used during the congressional debates highlighted the difficultly of transposing and translating program guidelines cross-culturally. And in several cases they revealed surprisingly superficial characterizations of Ugandan culture and sexuality, rarely emphasizing the historical and social complexity of AIDS prevention in the country.

Most depictions of Uganda’s program in the congressional record rightly focus on the issue of behavior change, but too often, as in the exchange between Capps and Smith, the debate came down to how important abstinence and faithfulness alone had been to Uganda’s success. Uganda’s far more nuanced and dynamic ABC program—integrating a variety of culturally relevant messages and dependent upon broader political and structural transformations—was lost in these discussions.70 In Republican testimony, behavior change came to be limited to two specific behaviors—being faithful and abstaining—that were familiar and appealing to conservatives in the United States but that on their own failed to encompass the broader set of strategies and social and political shifts that had enabled successes in HIV prevention in Uganda. Behavior change came to represent personal responsibility for one’s self, a discussion that was infused with references to Ugandan “tradition” and thinly veiled acknowledgment of Uganda’s conservative religious and political environment.

In the debates over PEPFAR, Uganda’s program was made the fodder for a particularly American political struggle—though one with global implications. Even so, this was not a battleground from which Ugandans were disengaged. American politicians sought out information about the Ugandan program in preparation to draft their own, and Ugandan First Lady Janet Museveni even traveled to Washington, DC in 2003 to help Republicans lobby for the dedicated abstinence funds in the PEPFAR legislation.71 By 2003, several high-level Ugandan government officials publically supported an emphasis on abstinence, especially for programs targeted to teenagers and schoolchildren. Janet Museveni, a convert to born-again Christianity, made the abstinence message a cornerstone of her agenda, spearheading youth abstinence programs through her office and, on World AIDS Day 2004, advocating a “virgin census” to encourage youth to remain chaste.

President Museveni and the First Lady were quoted in testimony during the U.S. congressional PEPFAR debates espousing a strongly proabstinence stance regarding sexual behavior in Uganda, with frequent references to the importance of self-control in the prevention of HIV infection.72 This was not in itself surprising or new; there had always been competing claims to moral authority in the debates over HIV/AIDS in Uganda. Male elders claimed “tradition” as a bulwark against shifting gender and generational relations that they viewed as the cause of the epidemic. Women also claimed authority from their positions as caregivers and mothers that bolstered their attempts at organizing to prevent the spread of the disease. Museveni, as the country’s most prominent political leader, would particularly be expected to chastise his population into behaving better. But PEPFAR’s funding stipulations asserted a moral discourse that was not rooted in Ugandan notions of proper gender and generational relations or ideas about political patronage and obligation. The rising influence of an American moral discourse rooted in a U.S. Christian conservativism reoriented Ugandan struggles from local relationships to global ones.

Accountable Subjects: A Policy in Action

With the implementation of PEPFAR in Uganda, new political and social capital was gained by cultivating connections with organizations and funding sources abroad. These connections often depended on a facility for engaging with American conservative agendas privileging accountability and personal responsibility. Perhaps most devastating for Uganda was the way in which behavior change was set in opposition to other approaches to HIV/AIDS prevention. In the wake of PEPFAR, Uganda’s broadly inclusive approach to program development was strongly challenged. Christians involved in prevention often told me that they wanted to change the meaning of Uganda’s ABC prevention plan from “abstain, be faithful, and use condoms” to “abstain, be faithful, and lead a Christian lifestyle,” seeking Christianity’s prominence in and dominance over disease prevention efforts.

The immediate effects of PEPFAR were felt most keenly among NGOs who sought to apply for program funds. Uganda’s prevention approach became more heavily fractured after PEPFAR’s implementation, with organizations forced to account for how their programs supported specific PEPFAR funding areas. Sometimes a program’s content had to be changed in order to satisfy these requirements. The prominent youth-focused group Straight Talk Uganda removed discussions about condom use from its educational radio shows after the American organization distributing PEPFAR funds to the group insisted that it do so.73 The founder of that organization, a British national who has lived in East Africa since the mid-1980s, told me how the environment surrounding prevention work became more politically tense in the years following PEPFAR’s implementation. The message of abstinence also became, in her words, “more rigid” and was increasingly informed by a Western view that understood sex to be driven by “only two things: desire and love.” Programs that addressed the broader cultural context that informed decisions about sexuality in Uganda (for instance, Uganda’s zero grazing program) were replaced by others better adapted to American grant requirements.

In order to seek PEPFAR funds, groups had to categorize themselves as addressing singular program areas, such as “abstinence/be faithful” or “condoms and related activities,” that did not necessarily reflect the ways Ugandans had previously imagined and categorized prevention strategies. These classifications left little room for the more nuanced partner reduction messages that the Ugandan ABC program had been known for. Public perception of PEPFAR in Uganda was also that it heavily favored prevention programs focused on abstinence. In its report on the impact of PEPFAR in 2005, Human Rights Watch quoted one Ugandan youth: “With funding coming in now, for any youth activities, if you talk about abstinence in your proposal, you will get the money. Everybody knows that.”74 PEPFAR’s own program report from 2005 also emphasized this focus, stating in the Uganda country section, “U.S. programming is increasingly emphasizing both A[bstinence] and B[e faithful].”75

The increase in donor funds for AIDS prevention also exacerbated the business-driven aspects of AIDS research and advocacy, in which a program’s dependence on donor aid worked to reshape objectives to meet or synchronize with donor concerns. This was a problem not limited to AIDS funding, but its effects were keenly felt in the realm of Ugandan HIV/AIDS prevention. The director of Janet Museveni’s Uganda Youth Forum, a youth-focused AIDS prevention NGO, articulated this dilemma when he told me in 2011 that, at the end of a grant’s cycle, “You are left with unfinished business. But when the next resource comes you have either become irrelevant or they are focusing on another development area.” PEPFAR represented a dramatic ramping up of both treatment and prevention programming, but it was marked by many of the problems that plague international aid in general. The terms of its funding were defined and driven by political agendas far removed from Ugandan communities. These agendas reshaped which messages were privileged and which became “irrelevant.” Another long-term AIDS researcher in Uganda told me, “To me, the response to HIV/AIDS in Uganda was more effective before than it is now. Right now I see the overcommercialization—the overtechnicalization, and then the commercialization. People respond to money, not to the problem. The period before [now] there was no money. People were responding to the problem.”

As international aid funding patterns have shifted, international NGOs devoted to HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment have become increasingly important social and economic institutions in Uganda. The effect of PEPFAR on Ugandan NGOs was perhaps most apparent in the rapid mobilization of Christian organizations, both local and international, that became involved in HIV/AIDS work. Large U.S.-based Christian NGOs played especially important roles in the implementation of PEPFAR; the largest grants under the 2003–8 program went to treatment projects (80 percent of PEPFAR’s funds are dedicated to treatment), but international Christian NGOs, including World Vision and Samaritan’s Purse, received significant grants for prevention.76 Other smaller evangelical Christian NGOs, including some started by Ugandans, have also received funds. In 2007 Shepherd Smith, the missionary who testified before Congress, received a grant for abstinence and faithfulness programs on behalf of his NGO, the Children’s AIDS Fund. His organization in turn relied on two Ugandan subpartners, Janet Museveni’s Uganda Youth Forum and the Campus Alliance to Wipe Out AIDS, the latter founded by a Ugandan born-again pastor.77 Both of these programs were dedicated to promoting an abstinence-only approach to youth education.78

These and other born-again organizations played a role in establishing the strong emphasis that Uganda’s PEPFAR grantees have placed on abstinence and faithfulness as prevention strategies. In 2007, 39 percent of all of PEPFAR’s primary grant recipients in Uganda listed abstinence and faithfulness as one of their program areas.79 In 2008, PEPFAR’s own statistics note that of 6.3 million Ugandans reached through prevention programs, more than 72 percent received an abstinence and/or faithfulness message.80

The emphasis on abstinence and faithfulness is not in itself radical in a country that for nearly fifteen years emphasized behavior modifications to reduce HIV prevalence. What changed dramatically under PEPFAR was how this message was being conveyed to the Ugandan population. Uganda’s early program was thought to be so effective in part because it heavily relied on peer-to-peer education and locally produced content to educate about HIV prevention. The message about behavior risk was also integrated with other prevention messages, including partner reduction and condom use education, rather than viewed as a separate program area.

In Kampala in the years following PEPFAR’s introduction the immediate sense was that AIDS prevention had become contentious and politicized in ways it had never been before. The experience of Straight Talk Uganda, whose program leader felt the group was on tenuous ground because its programs were not perceived as sufficiently proabstinence, gives only a partial picture. Prevention was a political issue, one shaped by international aid and Uganda’s relationships with U.S. conservative lawmakers. In the years following PEPFAR’s introduction, religiously infused prevention activism became a platform on which students and other young people could advocate for new attitudes about sex that were viewed as more aspirational, more empowering, and (from certain perspectives) more “moral.” Troublingly, these messages were often placed in opposition to other prevention strategies that had previously been common in Uganda (the “zero grazing” program, or Straight Talk Uganda’s long-form radio shows that emphasized peer-to-peer sexual education) as well as those approaches that most often contrasted with behavior change in global debates about prevention during this period (biomedical interventions such as serostatus testing and condom distribution).

A Fractured Landscape: The Abstinence-Only Approach versus Condoms

At the 2006 World AIDS Day rally in downtown Kampala’s Centenary Park the heightened tension between prevention strategies and advocacy groups was evident. Various HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention groups had gathered to celebrate their work in a leafy plaza off Jinja Road, a main downtown thoroughfare. Speakers took turns talking about the ongoing challenge of HIV/AIDS in Uganda. A group of students from UHC, one of the local churches active in promoting abstinence, were carrying banners and signs reading abstinence pride and abstinence is the only way of preventing aids that they had painted that morning at the church. During a presentation by another group, which mentioned its condom distribution program, members of the church group booed and shouted “Abstinence oye!” Throughout the rally any mention of the word condoms was met with a similar reception.

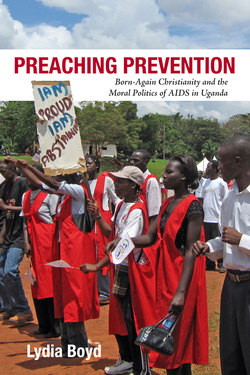

The apparent faultiness of other prevention methods was a fact often brought home by Christian abstinence activists in the years I lived in Uganda. A PEPFAR-funded student newspaper managed by a church-affiliated group on the university campus once ran a story explaining the “nine meticulous steps” involved in putting on a condom correctly. One young woman asked me, “If you can’t be consistent with coursework, how can you expect to use condoms consistently?” Another pastor’s presentation on youth sexuality in 2006 included a slide with a magnified sperm next to much smaller sexually transmitted viruses, the (misleading) lesson being that these diseases are so small they can permeate the latex in condoms. And a commonly repeated myth circulating among born-again Christian youth during a visit to Kampala in 2010 was that condoms cause cancer. This backlash against condom use was generated by the belief espoused by many Ugandan born-again activists, that abstinence (and, later, marital faithfulness) was the only way to prevent HIV/AIDS. In the years following PEPFAR’s introduction the mobilization of religious actors and the increased funding for abstinence-only programs contributed to a growing environment of antagonism among HIV/AIDS groups in the country. Editorials in newspapers and speeches by politicians often offered support for one side of the abstinence argument or the other. The Church of Uganda, which had in earlier years demonstrated a relatively inclusive approach to prevention strategies (at times even counseling condom use), by this time had embraced a far more antagonistic stance regarding condoms. Church leaders adopted rhetoric condemning adultery and other “sexual sins” and promoted condom use only within marriage. Public rallies in central Kampala encouraged youth to consider abstinence the only way to prevent AIDS (see figure 1.1).

One of the most prominent church leaders to emerge during this period was Pastor Thomas Walusimbi, the founder of UHC, a congregation I will describe in greater detail in subsequent chapters. Pastor Walusimbi positions himself in Ugandan AIDS circles as a moral reformer, encouraging “appropriate” behavior as a way of preventing HIV/AIDS. He expertly emphasizes how abstinence and faithfulness are Ugandan cultural values that have been undermined by foreign AIDS agendas that he views as biased against a faith-based approach to HIV/AIDS prevention. During a speech on AIDS leadership given on the university campus in 2007 he characterized his work as a struggle against a foreign AIDS prevention establishment that is populated by experts who are “liberal, faithless, and have no families.” His message appealed to conservative American Christians, who also saw themselves fighting a moral battle against a nonbelieving, liberal establishment, as well as to an African audience for whom calls for a reassertion of “traditional” African gender and family norms in response to the social disorder of HIV/AIDS had become common. For young Ugandans, however, Walusimbi’s narrative of resistance to the corrupt influence of seemingly amoral foreigners provided a message about their own self-empowerment and global influence that was deeply appealing. When I interviewed him, Pastor Walusimbi elaborated on this argument, noting, “Africans have been so relegated to the backseat of development and modernism for so long. And there is a sense in which we always receive, we never give, we never create. Our stories are told for us. It really makes me weep. Even when we have a successful story, like our HIV/AIDS story is a successful story. Even then someone has to come and say this is what you did, this is how you brought HIV/AIDS down.” Walusimbi claims that Uganda is not recognized for the success it had curbing HIV prevalence primarily because foreign HIV/AIDS policy makers resist talking about morality in the context of AIDS. Ugandans, he noted, are “religious, we’re family oriented.” Therefore, he argued, the people are responsive to a message of abstinence and faithfulness. As I have outlined above, the story of Uganda’s success is far more complicated than Walusimbi would have it be. But the rhetoric he uses to couch his criticisms is attractive, emphasizing Ugandans’ own moral authority and autonomy in the fight against AIDS—a fight that is now, undeniably, driven by a global economic and political agenda far removed from Ugandans’ home communities.

FIGURE 1.1. “Safe sex is no sex!” rally in support of abstinence, Kampala, October 2006

While Walusimbi frames his protest against the perceived intrusion of external funders and their “amoral” agenda, his message gained prominence because of the worldwide controversies surrounding American HIV/AIDS policy. He characterizes his message as one of Ugandan youth empowerment, but the message’s power is derived from a connection to international—and especially American—Christian discourses regarding morality and AIDS. The meaning Ugandans attribute to Walusimbi’s message about personal accountability and self-control is an issue I take up in later chapters. But the landscape of AIDS activism in the early years of the twenty-first century, an era deeply shaped by a compassionate response on the part of President Bush’s conservative religious base, can be followed in Walusimbi’s rhetoric.

Conclusion

In the late 1980s and into the 1990s Ugandans did in fact adapt their behavior, delaying sexual debut and reducing their concurrent partnerships—effectively abstaining and becoming more faithful, thus reducing HIV prevalence in the country. But the story of PEPFAR is a story of how behavior change was taken out of the broader structural and cultural matrix that had brought it force and shape and how it was given a new kind of agency through the ideals of “compassionate care” championed by the U.S. government. Starting in 2003, when behavior change was adopted as a buzzword by President Bush and his advisers, abstinence and faithfulness had evolved into a singular abbreviation for individual choices that emphasized personal accountability for disease risk and prevention—choices that could be promoted and exported globally. This was an interpretation of prevention success that buttressed other objectives of American humanitarianism of the era, an orientation to compassionate aid that helped outline and reinforce the dominant frameworks of neoliberal social action—autonomy and individual agency—that often obscured alternative ethical practices and modes of action that had figured prominently in earlier Ugandan efforts to mobilize against the AIDS epidemic. In chapter 2, I take up the Ugandan context more directly, focusing on the history that lead up to the introduction of PEPFAR. This is a history not of the epidemic itself but of forms of moral activism in the face of social change, activism that informed the more recent iteration of moral authority so effectively claimed by Walusimbi and his peers.