Читать книгу On Vanishing - Lynn Casteel Harper - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

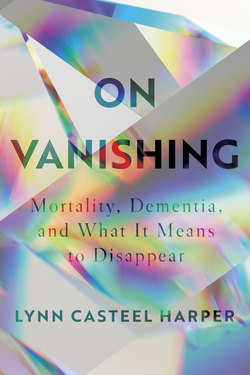

On Vanishing

I HAVE OFFICIATED ONLY ONE MEMORIAL SERVICE IN which I thought the dead person might come back. Dorothy was 103, and she was known for surprise reappearances. Dorothy had resided in an independent living apartment at the retirement community, and I had visited her on the few occasions when she had come to the Gardens to recover from an illness. I had learned over the course of these visits that as a teenager, she had left home to become a stage assistant to Harry Houdini—against her parents’ wishes, of course. What did a nice Methodist girl, a preacher’s daughter, want with an older man—a Vaudeville magician, no less—rumored to be a Jew, the son of a rabbi? Only after Houdini and his wife, Bess, visited Dorothy’s parents and promised to care for her as their own daughter did her parents relent.

In Houdini’s shows, Dorothy would pop out from the top of an oversized radio that Houdini had just shown the audience to be empty, kicking up one leg and then the other in Rockette-style extension. Grabbing her at the waist, Houdini would lower her to the floor, where she would dance the Charleston. In another act, she was tied, bound feet to neck, to a pole. A curtain would fall to the floor, and voila!—she would reappear as a ballerina with butterfly wings, fluttering across the stage. At the end of each night’s performance, Dorothy stood just off stage next to Bess to witness Houdini’s finale: the Chinese Water Torture Cell. A shackled Houdini was lowered, upside down, into a tank of water from which he escaped two minutes later. Dorothy knew how he accomplished this stunt—what was often deemed his “greatest escape”—but she never broke confidence.

Dorothy was the last surviving member of Houdini’s show. Long after his death, she attended séances on Halloween, awaiting communication with the Great Houdini—which, apparently, was never forthcoming. Eighty-five years after Houdini’s death, now she, too, had died. Each time I had visited her, I had felt her end was imminent. Already a petite woman, she seemed to grow smaller and smaller, until I was sure I would find her one day simply gone. But somehow she persisted—until she died about three years into my tenure.

As I prepared for her memorial, I imagined her doing one of her famous acts at the service. Instead of an oversized radio, her legs would kick open and emerge—up one, up two—from a once-closed coffin. Back to do the Charleston one last time. Or, breaking free from the chains of death, she would pirouette through the parlor in her butterfly wings. Instead, her son, who was in his eighties and also lived at the retirement community, opted for a casketless memorial service rather than a traditional funeral, and this somewhat allayed my anxieties about the coffin popping open. While a reappearance out of thin air seemed less likely, I knew by then that anything was possible with her.

Dorothy went to her grave without ever having revealed Houdini’s secrets, true to the vow she took at seventeen. I wonder what it is like to hold the keys to illusion, to know how to unbind one’s self, to learn the mechanisms of vanishing, to feel the weight of magic’s wisdom. Had she not been so scrupulously loyal, perhaps she could have helped the rest of us solve the riddle of how to vanish well.

•

I came of age in the 1990s when terms like “the right to die,” “persistent vegetative state,” and “advance directive” infused public discourse, and debates raged over euthanasia. In grade school, I became vaguely aware of Nancy Cruzan, a resident of my home state of Missouri, and Terri Schiavo—women who could not articulate their end-of-life wishes, whose bodies became the site of fierce political contestation. Dr. Jack Kevorkian was solidly a household name. In defiance of the law, he had helped dozens of seriously ill patients end their lives. His visage saturated the media, even appearing on a 1993 cover of Time with the title “Doctor Death” and the question “Is he an angel of mercy or a murderer?” It was only recently, however, that I learned of Kevorkian’s first client, a fifty-four-year-old English teacher from Portland, Oregon, named Janet Adkins. Diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, she could and did articulate her wishes and decided to make herself gone before the disease got the chance.

At a press conference shortly after his wife’s death, Ron Adkins read from Janet’s suicide note: “I have decided for the following reasons to take my own life. This is a decision taken in a normal state of mind and is fully considered. I have Alzheimer’s disease and do not want to let it progress any further. I do not want to put my family or myself through the agony of this terrible disease.” One week after beating her sons at tennis, according to reports, she lay supine in the back of Kevorkian’s 1968 VW van in a parking lot in a Detroit suburb. In her arm: an IV hooked to the pathologist’s own invention, the Thanatron, which delivered heart-stopping potassium chloride into her bloodstream.

Janet Adkins’s sympathizers pointed to the horrific prospect of this dementing disease’s pathology and her calculated courage. While she could still act on her own behalf, in what she had called in her note a “normal state of mind,” Janet Adkins headed off what she imagined as agony for her future self and her family. A pianist, Janet Adkins feared losing music, reportedly telling her pastor, “I can’t remember my music. I can’t remember the scores. And I begin to see the beginning of the deterioration and I don’t want to go through with that deterioration.” Perhaps the scores might degenerate into strung-out smudges of black, and she might find notes tangled, unable to fight themselves free to make melody. Perhaps her deterioration would be depleting in every way; it would be saturated with sorrow; it would require heroic fortitude. Perhaps her family would be drained in Sisyphean service to a Janet Adkins unable even to thank them. I imagine Janet Adkins wished to spare her loved ones the torment of her slow self-disappearance.

In the days leading up to Dorothy’s service, I read the tributes to her that appeared in major newspapers. I learned that she was the last of two hundred women to audition for Houdini’s show and had instantly dazzled the illusionist. After her contract with Houdini had ended, she went on to create a Latin dance called the “rumbalero” and to appear in several movies, including Flying Down to Rio with Fred Astaire. In her later years, she donated $12.5 million to build an arts center.

Reading these tributes prompted me to consider the story of my grandfather Jack, whose life—while not as glamorous as Houdini’s assistant’s—had seemed remarkable to me in its own right. A World War II veteran, Jack received the Distinguished Flying Cross for rescuing a fellow pilot by making a tricky, unauthorized landing in the Himalayas. Upon his return from the war, Jack had considered becoming a band teacher but instead pursued a career in medicine. He played jazz trombone in dive bars at night to pay for medical school. Jack was a committed and smart country doctor. He made house calls and forgave patients’ debts. He delivered babies and aided the dying. In the days before defibrillators, Jack once frayed a lamp cord, plugged it in, and shocked a patient to revive him. In retirement, he owned and helped to operate a local pharmacy. Jack was an avid hobbyist—always working in his woodshed or on his computer or on perfecting his omelets. He traveled the world as an ambassador with Rotary International. He maintained his passion for music, singing solos at church, playing the electric organ for his grandkids, and leading songs at Rotary meetings well into his eighties.

The Jack of all these activities—and the Jack who had the ability to narrate them and their importance to him—steadily vanished in his final years. On his eightieth birthday, eleven and a half years before his death, he could not keep score in a simple dice game we played. This singular memory helps me to date the duration of his dementia. At the time of Dorothy’s death, Jack was living in an assisted living facility that specialized in memory care. Jack would soon thereafter move to a nursing home where he lived his last two years. If not in bed, he was in his wheelchair at a table with other old war veterans in wheelchairs. He said very few words.

When I told a minister friend about my grandfather’s move to the nursing home, she reflexively responded: Oh, so he’s gone. Her words reminded me of another friend, who told me that she promised her father that if he ever gets dementia, not to worry, she will take him on a “nice walk to the edge of a cliff.” She then made a quick pushing motion—gone. It seems persons with dementia are more subject to being pronounced gone—to being pushed off the proverbial cliff—than persons with other kinds of progressive illnesses. While my grandfather’s life, in many respects, had “shrunk,” he certainly was not gone to those who knew and loved him. But I felt the push toward his erasure, and I wanted to know who or what was doing the pushing.

A couple of weeks after Dorothy’s memorial service, I attended a workshop on spirituality and dementia, where I first learned of the late British social psychologist Tom Kitwood, who, in the 1980s and ’90s, had developed a new model for providing care to persons with dementia. Challenging the old culture of care that viewed dementia patients as problems to be managed, as bodies in need of physical care and little else, Kitwood argued that people with dementia should be engaged with as complex individuals living within complex social environments. From what I gleaned at the workshop, I sensed that his approach to dementia might help me better understand what contributes to the invisibility of persons with dementia.

In the coming months, I read his seminal work, whose title alone attracted me: Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First. It seemed telling that a reconsideration of dementia would entail something as seemingly obvious as centering the person—as giving persons preeminence in their own lives. Most of the research on dementia had ignored the impact of the social environment on people with dementia, and on their disease process. Kitwood offered a profound corrective. He observed the ubiquity of what he called “malignant social psychology” in relation to persons with dementia. Through close observation of daily interactions between caregivers and dementia patients, Kitwood identified seventeen malignant elements that promote the depersonalization of persons with dementia: treachery, disempowerment, infantilization, intimidation, labeling, stigmatization, outpacing, invalidation, banishment, objectification, ignoring, imposition, withholding, accusation, disruption, mockery, disparagement.

Kitwood argued that care settings shaped by malignant social psychology can actually accelerate neurological decline. He critiqued the “standard paradigm” of dementia, which in his view often blamed only the organic progression of dementia for the decline that sufferers experience. The silent, stigmatizing partner in this dynamic—that is, the cultural bigotry against both cognitive impairment and old age—gets off scot-free. The process of dementia, according to Kitwood, involves “a continuing interplay between those factors that pertain to neuropathology per se, and those which are social-psychological.” Herein lies the frightening and hopeful prospect: the person with dementia does not simply disappear on her own. It is not just a matter of the private malfunctioning of her private brain. It has to do with our malfunctioning, our diseased public mind.

Not long after I read Kitwood, I walked into the program room and found Ruth yelling and pounding her fists on the table. She had recently moved to the dementia unit, where I had met her a few days before during my rounds. At that time, Ruth had been unhappy about her move but not distraught like she was now. Seeing my shock, an activities staff member explained, “She’s been terrible to us—yelling out bad things at everyone who walks by. She said she was hungry, that she wanted lunch. But she just ate lunch, so I got her pudding for a snack. And she threw the pudding at me, and it splattered all over the floor. Then she called me a bad name. I’m done; I’m just done.” She turned her back to Ruth and walked away.

Understanding Kitwood’s malignant social psychology helped me unpack this brief encounter. There was infantilization: Ruth was not permitted the food of her choice, because she “just ate lunch.” There was ignoring and objectification: the staff member talked over and about the resident as if she were not there, as if she were a nonentity. There was imposition: overriding Ruth’s stated desire, the worker insisted she must have a snack instead of a meal. There was disparagement: the staff member was clearly angry with Ruth, blaming her for her bad mood. There was withholding and banishment: the staff member left Ruth, declaring, “I’m just done.” Ruth was left alone. Malignancy now hemmed her in. I watched a dining room staff member approach Ruth. “What would you like?” he asked. “A sandwich or something,” she replied. He returned from the kitchen with a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. Ruth immediately bit into it. “Thank you, I never thought I’d be this happy with a peanut butter and jelly sandwich,” she said.

By this relatively simple act, the staff member had unraveled a bit of the malignancy, but the task of undoing malignant social psychology cannot rest only on direct caregivers. Kitwood understood malignant social psychology as “in the air”—part of our cultural inheritance, not a phenomenon to be blamed on (or solely remediated by) individual caregivers. Malignant responses to dementia, in Kitwood’s analysis, revealed tragic inadequacies in our culture, economy, and medical system, which often define a person’s worth in terms of financial, physical, and intellectual power.

That certain mental powers determine one’s moral standing reflects what the bioethicist Stephen Post calls our culture’s “hypercognitive” values, a phrase he first used in his 1995 book, The Moral Challenge of Alzheimer Disease. Revisiting the concept in a 2011 article, Post highlights the “troubling tendency,” in our hypercognitive culture, to “exclude human beings from moral concern while they are still among the living.” Our particular veneration of cognitive acumen generates “dementism”—a term Post uses to describe the prejudice against the deeply forgetful.

Transcending the acts and intentions of discrete individuals, systemic dementism exists in structures that overlook, minimize, or actively undermine the needs of persons with dementia. For example, assisted living facilities, in which approximately seven out of ten residents have some degree of cognitive impairment, are underregulated—leaving people with dementia particularly vulnerable. A severe shortage in the United States of geriatricians, who are often best equipped to provide ongoing clinical support for older persons with dementia, signals a prejudice in the medical system.

The overuse of psychotropic drugs, which carry risky side effects for elders with dementia, is another sign of dementism. Unlike medicines used to treat the cognitive symptoms of dementia, these psychotropic drugs, which include antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics for anxiety, and antiseizure medications, are used to manage certain behaviors associated with dementia—and are not approved by the FDA for this specific use. Antipsychotic medications are particularly hazardous for older adults with dementia, greatly increasing the likelihood of stroke and death. A study published in 2016 in International Psychogeriatrics revealed that only 10 percent of psychotropic drug use among people with dementia is fully appropriate. And yet pharmaceutical companies have pushed the use of such medications for persons with dementia. In 2013, Johnson & Johnson paid a $2.2 billion settlement for the improper promotion of Risperdal, a drug designed to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, for use with dementia patients, despite the company’s knowledge of its serious health risks for this population.

As I consider religious institutions within my own Protestant circles, I notice how rarely seminaries offer much if any training to future pastors about aging and dementia. Churches often pump tremendous resources into ministries for young families and children, with little attention to elders—let alone elders with dementia. Progressive churches like mine, which faithfully fight for racial, gender, and economic justice, often fail to take into account ageism and the plight of people with cognitive impairment. Redressing malignant social psychology is not as easy as serving peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. Remediation is needed at every level.

It occurs to me that the possible roots of dementism may lie in a discomfort related to the body; I sense that our culture is fearful both of the body’s powerlessness and its power. As I prepared for Dorothy’s memorial service, I reflected on such corporeal conundrums. The body is unwieldy and dies. A source of perpetual conflict, the body is at once our home—there’s no escaping it—and our battleground, as we struggle to break free from its inevitable demise. We want the box to pop open to reveal our still-kicking legs; we want to shed impossible shackles.

I suspect those bodies in need of hands-on care by others are objects of cultural contempt, because they lay bare our collective fear of the body’s fragility and dependence. Perhaps those bodies most charged with the hands-on care of these bodies also bear the taint. The same malignant forces that marginalize the old and the cognitively impaired also marginalize their caregivers, who are often the most economically vulnerable and politically invisible people in American society.

The philosopher Eva Kittay notes that the particular demands of caregiving and the traditional relegation of this work to women or servants make care workers “more subject to exploitation than most.” According to a 2018 report released by the Paraprofessional Health Institute, nursing assistants who work in nursing homes—the majority of whom are women of color—suffer workplace injuries at nearly three and a half times the national average. Half of nursing assistants have no formal education beyond high school, and nearly 40 percent rely on some form of public assistance. Fifteen percent of nursing assistants live below the federal poverty line, compared to 7 percent of all U.S. workers.

Nursing assistants spend more time with residents than any other clinical staff, providing a median of 2.2 hours of hands-on care per resident per day. That this occupation, so central to resident care, is both hazardous and poorly compensated reflects the low cultural value placed upon those who perform it and, by extension, their clients. I can count on one hand the occasions I saw administrators on the Gardens’ dementia unit spending time with residents and staff. This absence reflected and reinforced the broader culture of invisibility. Perhaps it is little surprise that both the vulnerable staff (often black immigrant women) and their patients (often immobile, voiceless, dependent) were relegated to the same space. The curtain is drawn, hiding them from view—a vanishing act with no scheduled reappearance.

•

Accompanying Dorothy’s obituary, many newspapers included a black-and-white photograph of her popping out of Houdini’s oversized radio—a prop that looked to me like nothing more than a coffin with dials affixed to it. Next to this box stood a tuxedo-clad, wild-eyed Houdini, his arms agape, holding a wand overhead as he presented his assistant, the “Radio Girl.”

The image made me think—perhaps irreverently—of the stories of Jesus’s empty tomb and the play of presence and absence that permeated early accounts surrounding his death. In Mark’s gospel, when women come to the tomb to anoint Jesus’s dead body, a young man dressed in a white robe—presumably an angel—appears to them and points to absence: to nothing but a heap of empty grave clothes. “Look, there is the place they laid him,” he says. The women look at where the body was. Offered only a brief explanation of the absence—“He has been raised; he is not here”—the women are granted no positive confirmation of Jesus’s whereabouts. They respond the way any God-fearing people would: they flee the scene, deathly afraid.

The scene has the right components of a magic show—an expectation of presence or absence (depending upon the setup) and a surprise reversal. I imagined Houdini at Jesus’s tomb wearing a white tuxedo and waving a magician’s wand overhead as he presented the empty space. The reversal, however, is askew, or it is, at least, incomplete. The dead body should be revealed as alive—not merely as missing. But the original ending of Mark, the earliest Gospel, includes no post-resurrection sightings of Jesus. The women at the tomb were to believe based on what was not there—a faith based on disappearance.

Uncomfortable with this silence and with the last image being one of women fleeing in fear—and perhaps intuiting the failed dramatic arc—Mark’s earliest editors added post-resurrection encounters with Jesus in the flesh, and not just with the clothes his flesh had once inhabited. The later Gospels chronicled rather detailed meetings between the risen Jesus and the disciples. Jesus shows them his feet, hands, and side; he walks through closed doors, breathes on them, and makes breakfast for them on the seashore. In John’s Gospel, Mary Magdalene mistakes the risen Jesus for a gardener, until he speaks her name. The disciples experience, with their senses, a newly constituted but still bodily Jesus—and thus gain what we moderns might call a sense of “closure” in the wake of Jesus’s traumatic death. When all seems lost, a magical, fleshly reappearance defies death’s despair.

Nevertheless, I am drawn to Mark’s original ending; it rings truer in light of the abundant absence that, to my mind, marks all earthly existence. The dead don’t often visit us again (imagine the silence at the yearly Houdini séance). The Population Reference Bureau estimates that 107 billion people have ever lived, which means that for every one person now alive, approximately fifteen people have died. There comes a tipping point in the timeline of our own lives when we know more of the dead than of the living. We all have forgotten much more than we remember. The proliferation of vanishing, more and more, is what we have to live with.

And yet disappearance does not necessarily mean obliteration. I hope that what remains might be enough, that beholding something as quotidian as a dead body’s dirty laundry might be enough to ignite and kindle undying devotion.

For all of his losses in old age, I have come to feel that my grandfather—Jack as Jack—did not vanish. He persisted, a complex conglomeration of the past and his new present. Jack would mock-sing into a saltshaker when good music came on in the nursing home dining room. What else but an affinity for life was behind the enjoyment of playing instruments, traveling the world, perfecting omelets, and singing into a saltshaker? Stooping over his wife’s coffin, deep in dementia, Jack said, “I don’t want to join you yet, babe!” What else but a will to survive was behind piloting a cargo plane across the treacherous Burmese Hump, scraping his way through medical school playing gigs in bars at night, and declaring at my grandmother’s graveside his desire to live? The essences behind his previous life endeavors seemed intact in Jack until the end—in subtle shades, often known only to those who spent time with him—while the activities that once embodied them had fallen away.

The mystics might say what is left is a truer, purer self. The dissolving of all doing, the stripping away of the via activa, makes straight the path for the naked, beloved self to emerge. The deconstruction of ego can facilitate a new freedom of being.

•

The definition of “vanishing point” seems to integrate apparent opposites. The point at which parallel lines receding from an observer converge at the horizon is also the point at which the lines disappear. The vanishing point is both unification and dissolution, the point of convergence and cessation.

If I stand still and watch a person walk away from me, she grows smaller and smaller, until she reaches the vanishing point. She has not vanished from the planet or from herself—she has vanished only from my view. If I move toward her, she reaches her vanishing point more slowly; if I move away from her, she reaches it sooner.

Kitwood argued that as the degree of neurological impairment increases, the person’s need for psychosocial care increases. What traditionally happens is the exact opposite. As the degree of neurological impairment increases, the person becomes increasingly neglected and isolated, further increasing neurological impairment—a vicious circle. Malignant social psychology hastens the vanishing point. Person-centered care, which aims to affirm identity and promote well-being, tries to keep the vanishing point far off, to keep the person with dementia in view as a unified whole. The benefits of person-centered approaches, including the reduced usage of psychotropic medications among residents in long-term care settings, have been well documented. The Alzheimer’s Association 2018 Dementia Care Practice Recommendations, a comprehensive guide to evidence-based quality care practices, names person-centered care as its underlying philosophy, pointing to research showing that individualized care decreases depression, agitation, loneliness, boredom, and helplessness among people with dementia, and reduces staff stress and burnout.

The vanishing at the vanishing point, however, is an illusion. A road does not cease at the horizon; it simply disappears from an observer’s view. The person with dementia exists beyond my capacity to keep her in my line of sight; she remains a person despite my (or anyone else’s) limited powers of vision. Still, we must reckon with the disappearing—even if it is, in some sense, illusory.

Leonardo’s Last Supper contains perhaps the most famous vanishing point. Our eye is pulled into Christ’s head at the center of the composition; it is the aggregating point. We are drawn to and through the mind of Christ—both to disappear there and to gather there. Christ dies on the cross (dissolution); Christ merges with the divine (unification). As we reach the vanishing point, we both dissolve and converge.

Having previously made arrangements with a Detroit funeral home for Janet Adkins’s remains, her husband, Ron, headed straightaway to the airport to catch his flight back to Portland on the afternoon of Janet’s death. “He wanted to get out of our jurisdiction as quickly as possible,” one prosecutor involved in the case told the Los Angeles Times. “He wanted to disappear.”

Ron Adkins publicly voiced support for his wife’s decision, but I wonder if he pled with her not to do it—that it might be his honor to be burdened by her. Perhaps he resented his wife’s determination that he should not be asked to do so. Perhaps he could come up with nothing more pressing in his life that would render caring for his wife a lesser good. Perhaps he was willing to risk their futures. He had purchased his wife a round-trip ticket, in case she changed her mind and wished to return to Oregon with him.

I have witnessed many loving partners unable to rise to the occasion—and perhaps this is what Janet Adkins wished to avoid. I have seen one spouse keep the other alive by any means necessary because the idea of being without the person was simply unbearable. Maybe Janet Adkins knew that love is blindness at times. Maybe the only person she trusted was herself, in the present—and a pathologist in Michigan.

I don’t think Janet Adkins wanted to kill herself—rather, she wanted to kill her future self, the deteriorated self she imagined, the self she worried would put her family “through the agony of this terrible disease.” The Janet Adkins on the tennis court and at the piano killed the projected Janet Adkins in a wheelchair, unable to find notes on an instrument whose name she cannot recall. The self-determining Janet Adkins killed the dependent Janet Adkins. The strong Janet Adkins killed the weak Janet Adkins, before the weak Janet Adkins got a foothold. The story is a familiar one: the strong subjecting the weak—the strong eradicating their fears through expulsion of the weak. Is this not the fascist impulse, the imperialist compulsion? Or might it be the compassionate impulse, the yearning to be free of unnecessary affliction? How blurry the distinction between exterminating weakness and alleviating suffering.

•

What does it mean to vanish well? After all, the result is always the same: you end up gone. There are no tricks to undo this finality. Magic’s familiar script—the sudden deletion into thin air; the breathtaking reappearance out of thin air—does not seem to apply in the end. The stage assistant’s role, however, may abide.

Perhaps, to vanish well entails allowing others to help unbind you, trusting them to keep your secrets. I think of Dorothy, who stood just offstage, offering a measure of knowing assurance, as Houdini attempted improbable escapes. We need compassionate attendants who help us in our final stages of disappearance, too. I think of my mother, soaking her dad’s feet in a tub of warm water; of the nursing assistants, tenderly lifting spoons to open mouths; of Ron Adkins, sliding Janet’s return ticket into his breast pocket. I imagine a world in which securing good support is not so hard, because living and dying with dementia is not so feared or fearful. For most of us, our vanishing will occur slowly and may mercifully give us time to gather willing assistants who know the illusoriness of disappearance when we reach the vanishing point.