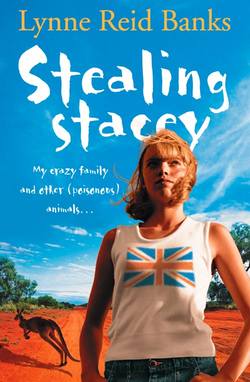

Читать книгу Stealing Stacey - Lynne Banks Reid - Страница 6

Chapter Two

ОглавлениеGrandma Glendine settled in with us.

I hated her being there, but not because of her so much. It was because I had to share Mum’s room. And Mum not only smokes – she snores.

“Mum! Roll over!” I’d shout when her snores were driving me wild. The most infuriating thing was that Mum simply refused to believe that she snored.

“It’s lies, I don’t! Dad would’ve told me.”

“Probably too stoned to notice.” I shouldn’t have said that. She just turned her back and her shoulders started to shake. I knew she was still crazy for him.

Somehow Gran – I’d decided to call her just Gran – arranged her things in my room. She used all that luggage as extra furniture. The trunk turned into a table. Gran wrote loads of postcards on it, all touristy pictures of London, beefeaters at the Tower, guards at Buckingham Palace, that kind of thing. Even some of Princess Diana. She said a funny thing about her, that I should have taken more notice of at the time, but I didn’t.

“I remember exactly where I was when I heard she’d died. I was skinning a kangaroo.”

I don’t know why I didn’t pick up on that. I just thought it was a joke or something. I sometimes think I’m not very bright.

The other suitcases were piled up and she stood things on them. She’d brought lots of interesting things with her.

There were postcards of pictures all painted in dots. I couldn’t make them out until she explained them. They were painted by Australian natives and were all in code. A fire was a bunch of red dots, for instance, and white dotted lines were trips their ancestors made in something called the Dreamtime, across the outback. That’s the middle of Australia where it’s all desert. And there were special kinds of dots for animals or their footprints, or curvy coloured lines for snake tracks. The animals were wonderful weird kinds. I loved those postcards and Gran gave me some to stick up on my side of Mum’s dressing-table mirror.

Then there were some wooden animals with burn marks on them. Big lizardy things called goannas, and snakes (I wouldn’t even touch those. God how I hated snakes, not that I’d ever seen a live one). She had miniature wooden things like long bowls and something called a throwing stick, for spears, she said. She gave me a boomerang, only where would I have space to try throwing it? She showed me a picture of a didgeridoo, a musical instrument, which is a long, thick pipe. It gets hollowed out by termites, and it’s so heavy you have to rest the far end, the end away from your mouth, on the ground. She told me women aren’t allowed to play it because it’s symbolic, you can guess what of!

She showed off her clothes. They were sort of naff in a way, but rich-naff, not like Mum’s shell suit that I told her not to buy at the Oxfam shop (but of course she did). It’s a sort of metal-pink. I die every time she goes out in it.

Gran took us out. Not on week nights, she was very hot on me getting to bed early so I wouldn’t be tired at school, but on Fridays and Saturdays. She took us for meals out, and not at the local dumps, either, except once we took her to one of the African cafés for the experience. I took her around the market a couple of times, she said she loved it, which was quite something, because it can be fun in the summer, but it’s pretty dismal in the rain. Mainly though, she wanted to treat us. Once we went to a Holiday Inn right up West and had a really swish meal with proper waiters. That was the night she took us to see the show at the Hippodrome. It was amazing. I’d never seen a live act before. She took us to loads of good movies too. We took taxis and minicabs everywhere, she wouldn’t ride the buses or trains.

She talked. How she talked! And she wanted me to talk, too. When I came home from school she asked me to tell her my whole day. I was used to slumping in front of the telly after school to chill out. Now I had to articulate. She soon spotted I hated school. She never mentioned the truant-cop, but I think she’d heard, or maybe Mum had ratted on me.

“It’s really bad not to like school, sweetie,” she said. (By now I’d lost count of all her pet names for me.) “You have to get your priorities right. School’s a top priority at your age.”

“It’s so boring.”

“It’s up to teachers to make learning fun.”

“Tell that to ours,” I said.

“Kids have to make an effort too,” she said. She fixed me with her eyes. She wasn’t reproaching me exactly, more sort of measuring me. “Isn’t there any lesson you like?”

I didn’t answer at once. I didn’t want to tell her I quite liked English, for some reason. I fancied myself as an anti-school rebel, like Loretta. But she kept her eyes fixed on me, so in the end I muttered that computer studies weren’t bad.

Gran brightened up. “Oh, good that you like computers! I’m surprised you don’t have one at home.”

I gave Mum a look. I’d begged, just about on my knees, for a home computer. I’d told her, like one million times, that my teacher said that was one reason why I wasn’t keeping up, cos I didn’t have a PC. I was pretty well the only one in my class that didn’t. (Well, that was what I told Mum anyway.)

“Now don’t start, Stace, you don’t need a computer!” Mum snapped at me. “It’s up to the school to make you keep up, without telling me I ought to spend hundreds of pounds we haven’t got.”

“Of course she needs one,” said Gran. “A good one, with a colour printer and a scanner and all the bits. Christmas is coming, isn’t that right, cherry pie?” and she winked at me.

“Glendine! Don’t even think about it, please!” said Mum. “I couldn’t accept it.”

“Rubbish! Why not?”

“Because… I don’t know why not. I just feel I couldn’t.” Typical Mum. Gran just smiled her big white smile. (Her teeth weren’t false. I knew because Nan’s were and I could tell the difference, close to.) I felt my heart sort of bob up and down. I knew I’d get a computer for Christmas and there wasn’t a thing Mum could do about it.

I had it all worked out by the beginning of December. Where I’d set it up would be in the living room. I’d surf the net and send e-mails and join chat rooms and play computer games. I might even use it for a bit of schoolwork.

But then in the end I didn’t get a computer at all. Because Gran got a better idea.

She told me it was a secret.

“Not a word to Mum yet! I’m going to kidnap you.”

“Go on, Gran. You’re just having me on, right?”

“I’m serious. I couldn’t be more serious if I tried.”

I couldn’t take it in at first. It was too amazing. She wanted to take me to Australia for the Christmas holiday!

I was, like, ecstatic. The more she told me about Australia, the more I wanted to see it. She made it sound so exciting. She had a wonderful book with coloured photos in. Everything looked so different from boring old England.

It seemed like the sun shone all the time, there was tons of swimming and sports, and lots of wildlife. I’m really into wildlife, on the telly, that is. There’s not much of it in south London – unless you count birds. And I saw an urban fox once. But foxes and pigeons don’t stack up against dingoes and koalas and wallabies and wombats and duck-billed platypuses. That’s aside from kangaroos, which have been my favourite animal since I had a Kanga and Roo toy when I was little. The snakes put me off a bit, but I tried not to think about them. Or the crocodiles. We’ve got no dangerous animals at all in Britain, unless you count the Loch Ness Monster and the Beast of Bodmin Moor, which nobody really believes in. About our most dangerous thing apart from Rottweilers is mosquitoes. (OK, adders. But in London? Get real.)

But what I wanted to see most was the outback, because I’d seen videos of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert and Crocodile Dundee. But it was because of Gran’s things, too, what she called her Aboriginal artefacts. I wanted to meet some of those people.

“There are big mobs of Wonngais where I come from,” she said carelessly. “I’ll introduce you.”

I was just so scared Mum wouldn’t let me go.

“Don’t you worry about that! You leave your mum to me.”

But before she could tackle Mum, something really radical happened.

When I think back to it now, I remember what a good day we’d had, the day before. First off, we’d had a row, because I’d been to Loretta’s, supposedly just for a sleepover, and of course we weren’t supposed to go anywhere, but we did. We sneaked out to a party and danced and, yes, we did drink a few alcopops, actually more than a few, but it wouldn’t have mattered – I mean we didn’t get legless or anything, we were just enjoying ourselves. But by the lousiest luck on earth, the son of a friend of Mum’s was there (the others were mostly older than us) and he must’ve ratted on me. When I got home the next morning, which was Saturday and Mum’s day off from the checkout, Mum was waiting for me. She was practically jumping up and down. It was just lucky for me Gran was there or I would’ve really copped it. Even as it was, Mum dragged me off to our room and had a hissy-fit and I had one back, but even the hissing was kind of muffled because we knew Gran was listening.

When I can’t yell back at Mum it all sort of turns inwards – I felt all screwed up inside and I just lay on the bed crying and feeling like it was the end of the world. Of course Loretta wasn’t going to cop it, was she. Just me. And Mum’d grounded me for two weeks, just when there were Christmas parties and other things coming up.

Then I heard Gran’s and Mum’s voices and I tried to listen, but all I could tell was that Gran was trying to calm Mum down. After a bit, Mum crept back into our room and sat down on the bed and said, in that little-girl way she has, “Gran’s on your side. She says it was only a bit of fun and I’m too hard on you. She says I should do more things with you and then you wouldn’t want to get away from me all the time and be rebellious.” (Can you imagine? She is so transparent. But it’s sort of sweet in a way, she just can’t play the heavy-mother game for long, it isn’t in her nature.) I sniffed and blew my nose and said, “Like what things?” I mean, what could she possibly have in mind that was interesting? But your parents can surprise you, just sometimes.

“How would you like to get your bellybutton pierced?”

I sat up on the bed and stared at her, eyes boggling.

“What?”

She said it again, and then she said something even more unexpected.

“I’ve always wanted a bellybutton ring. We could do it together.”

Well, of course, that did it. Mother and daughter bellybutton rings. I ask you. Who could hold out against that? Because I knew as sure as eggs is eggs (as Nan says) that having any part of her pierced was the last thing on earth Mum had ever dreamt of, I mean otherwise she wouldn’t still be wearing clip-on earrings and always losing them.

So off we went that same day and had our bellybuttons pierced together at that place on the high street. She went absolutely white as a ghost when it was her turn and I suddenly felt I loved her. You know when you sort of love someone all the time, in the background, with rows and sulks and stuff going on in the foreground, you forget to really feel it, and then unexpectedly you do feel it and it nearly knocks you down. I gave her a big hug and said, “You don’t have to do it if you don’t want to, Mum,” but she said she did want to and in she went to the torture chamber, brave as a lion, and had it done. And now we both had a sort of secret together because she said she’d never show hers, it would just be for me to know about. (She went all quiet for a bit after she said it, and I knew she was thinking “Except Dad if he ever comes back.” But I was pretty sure he never would, and she knew that, so she didn’t say it aloud. She hates me telling her to get real.)

Afterwards she took me out for a pizza and it was a good laugh. We talked, mainly about our sore bellybuttons it’s true, but a bit about other things, and I told her all about the party and I heard myself promise never to go to one again where there was alcohol, until she told me I could. (To be honest, it was a bit scary, practically everyone there was older than us and there were some dodgy types among the boys – I mean apart from that rotten sneak. One of them touched my tummy. I didn’t tell Mum that of course.)

In the afternoon we met Gran and she took us to a movie, her choice. She wanted us to see an Australian film called Rabbit-Proof Fence. It was really wonderful, all about two Aborigine sisters, young kids, who run away from this horrible school and walk hundreds of miles through a desert to get home. It was really sad, especially at the end when you saw these women who were the real girls, grown old. We all cried, even Gran, who’d seen it before.

So that was our good day.

Then it happened.

I heard the phone ringing in the middle of the night, and felt Mum get out of our bed. Then I went back to sleep. In the morning, she was gone. Gone! Just like that! I couldn’t believe it, but I had to after I found the note on my side of the dressing table.

“Stacey, I’m sorry, I have to go. Dad’s in trouble. Gran’ll look after you. I’ll be back soon, I hope. Love, Mum.”

She’d taken some of her things. I rushed into my bedroom that was Gran’s now. I didn’t even knock. I woke her up and showed her the note. I was in a state, all shocked and crying.

Gran sat up in bed. She had a shiny, bare night-face. She read the note. “Oh the precious little idiot,” she said. “Wouldn’t I like to give her curry!”

“Curry!”

“That’s Australian for a hot telling-off.” Then she hugged me tight. “Don’t you cry, sweet-face. Grandma Glendine’s here. She’ll take care of you.”

I pulled away. “But where’s she gone? She couldn’t go to Thailand, she hasn’t got a passport!”

“Let’s try Greville Drive, it’s closer.”

“You mean Dad’s come back?”

“I wouldn’t wonder, if he’s phoned her to say he’s in trouble.”

It was Sunday, luckily. Gran told me to go and put the kettle on while she got dressed. She had her tea and then she called a minicab and we drove round to Greville Drive. I knew it was number six because Mum went there once just to look at the place. She’d have gone more times if I hadn’t stopped her. It was like she was addicted, just to seeing where he lived… sick! With Gran, I stayed in the cab. I didn’t want to see Dad, just Mum. I wanted to see her so badly, it was like there wasn’t anything else that mattered. I was sort of sniffing-crying, trying to hold it back. Gran marched up the path and rang the bell. She soon came marching back.

“No good. It’s some new people. He hasn’t been back there. They could be anywhere. I can’t believe your mum. What a prize little nitwit. After the way he treated her, he only has to crook his little finger and she goes running back! And to God knows what sort of a mess.” She slammed the car door and told the driver to take us home. It was like sitting in a minicab next to a volcano. I could almost see the steam coming out of her blue rinse.

* * *

So me and Gran turned into flatmates.

She cooked sometimes, but she liked it better when I did. She sat in the kitchen on a high stool, chewed her gum, and watched me. I tried out some of the stuff I’d seen on the TV cooking programmes. Mum’d never let me, she said I used too many pots and then left her to wash them up. (She had a point. I hate washing up. I’d almost rather have a dishwasher than a computer.) Gran thought I was brilliant. Every time I put in a couple of grinds of pepper or beat up some eggs, she acted as if I was Jamie Oliver. This was nice, but I was missing Mum like crazy. I got more and more upset that she didn’t phone. Love is really weird. When she was there, she drove me mad. Now I’d lie in our bed wishing she was snoring beside me, or puffing on a fag, though I always used to shout at her that she’d set the bed on fire.

“She’ll be back, dolly-face, and most likely with a flea in her ear,” Gran said. “Serve her right. Women shouldn’t be doormats. But we’ll have to give her loads of TLC.” (That’s Tender Loving Care, in case you don’t know.)

At last Mum phoned. She’d been gone three days and fifteen hours.

“Mum!” I screamed down the phone. “Where are you? Are you coming home?”

“No, Stace, I can’t. I’m just ringing to see that you’re all right.”

“Well I’m not! How could I be, without you?”

“You’re actually missing me?” she said, in a really surprised voice.

“Of course I am!” I yelled.

“Why? What do you miss?”

I felt furious and at the same time, lousy. She was as good as saying I’d never appreciated her, never let her know I loved her. “Everything,” I said. “Even your snoring. Please come home.”

There was a long silence and then she said, in a muffled sort of voice, “Stace, listen. Don’t tell Glendine this – she is still there?”

“Yes.”

“Oh, good. Well, don’t tell her, but Dad’s… he’s sort of on the run.”

“Mum! What’s he done?”

“I can’t tell you. But he’s hiding out and I have to stand by him and help him. He’s got no one else.”

“What about the slapper?”

“She’s gone.”

“Did you – did you know they went to Thailand?”

“Yes. That was where he… got into trouble. Where she got him into trouble. He managed to pinch his ticket back from her before she left him, and fly home, but the police there put the ones here on to him. Now, don’t think badly of him, Stace—”

“Oh, no, I wouldn’t do that!” I said, really sarky. I was feeling sick and scared. What could he have done? It had to be something to do with drugs. I’d heard plenty about men luring women into carrying drugs for them, but never the other way round. I hated to feel Dad was weak, that she’d used him.

“It wasn’t his fault,” Mum almost shouted, in a very strong voice. “It was her, that’s who it was, and then when she’d landed him in it, she ran out on him when he needed her most, the rotten little tramp. I knew she was no good, those tarted-up middle-class ones with their snooty voices are the worst! Stacey, I just want to ask you, can you manage for a bit longer till I sort things out for Dad? I wouldn’t ask, but this is a real emergency.”

All my helpless, angry thoughts suddenly came together to form one word. One answer.

Australia. On the other side of the world. An escape from everything: this lousy little flat; school; the miserable weather we were having, all muggy or else dark and pissing down with rain all the time; Christmas on our own with no money; Dad in a mess, Mum stuck with him… No. None of it was my fault. I didn’t have to put up with it or face it. I could get away from all of it. Australia!

I knew I should tell her. I knew it. But I thought she’d say I couldn’t go.

“I’ll be all right, Mum,” I said. And I even heard myself add, “Give Dad my love.” But I didn’t mean it. Not really. I was ready to clobber him for taking Mum away from me.

I didn’t tell Gran about the call.

That same day, she asked, sort of carelessly, “When does school break up?”

“On the seventeenth.”

“Oh, right.”

When I came home from school on the last day of term, I found the flat in, like, chaos. I thought at first we’d been done over. Then I looked closer and saw the suitcases. Her sunflower ones, open. One of them was full of summer clothes. Not her size. Mine.

I picked up a green and purple bikini and dropped it again. “Gran! What’s going on?” I shouted.

She popped out of her (my) room. She sort of sang, “Glen-dine’s been shop-ping!”

“I can see! What’s it all for?”

“It’s all for you, cookie. I hope you like it. I’d have taken you to help choose, but we’re leaving tomorrow, there was no time.”

“Leaving? Where are we going?” But I knew. And suddenly it was real. She was kidnapping me, just as she’d promised!

“We’re flying to Perth, love,” she said. “Not Perth, Scotland. Perth, Australia.”

“What? But we can’t! Don’t I need a passport?”

“You’ve got one, ducky!” she said, triumphant. She held up a new red passport. I took it from her and looked at it. There was a picture of me that we’d had taken in a booth one day when I was out with her, she’d said she wanted it for a souvenir.

It struck me a lot later that she must’ve been planning this for a long time. She’d have needed Mum’s signature on the form, so she must’ve forged it. But I never thought of any of it. Not at the time. I was too upset about Mum and Dad, and now there was something really exciting going to happen to make up for it.