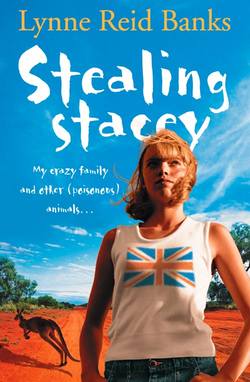

Читать книгу Stealing Stacey - Lynne Banks Reid - Страница 7

Chapter Three

ОглавлениеI had my doubts – give me that much. That night while Gran was having one of her endless baths – she’d imported a big bottle of bubble bath, which I could hear her frothing up with her hands till it must’ve looked like she was lying in a huge milkshake – I phoned Nan and told her I was going to Australia with my other grandmother.

Nan was already in a state about Mum bombing off. She’d been round a few times to see I was all right. She didn’t like Glendine, I could tell. She always turned her head away, as if Gran was too bright for her eyes. Now Nan said, in her pursed-up-lips voice, “I don’t think it’s right, her carrying you off like that without so much as a by-your-leave.”

“How can we ask Mum, when she’s gone off?”

“She’ll be back. Then what’s she going to say?”

“I’m leaving her a note. And you can explain. Besides, I’ll be back before school starts. Nan, I want to go!”

Nan fussed and carried on. She didn’t want me to go, but I remembered Mum’d said she was jealous of Gran, because of her throwing her dosh around and giving us treats. In the end I just said, “Well I’m going. I’ll send you a postcard with a kangaroo on it, bye.” That was that, because I put down the phone. Yeah, rude. But if you don’t bring Nan’s phone calls to an end she can witter on at you for hours.

What bothered me much more, after I’d hung up, was that I hadn’t told her I’d heard from Mum. I just left her to worry. But wouldn’t she have worried even more if I’d told her about Dad being in trouble with the law?

I’d never flown before. It was a long flight but I didn’t care. I loved it. I wasn’t even impatient, because Gran told me her self-hypnosis technique for long flights.

“You settle down and put your seat belt on, and you think, ‘Nothing to do but sit here and read magazines and watch movies and eat and drink and sleep and look forward to Australia!’” I did that and it worked. I suppose I’m naturally lazy, like my teacher says (what she actually said was, I was seriously talented at laziness), because doing nothing for thirteen and a half hours didn’t bother me a bit.

I wanted to see if Gran would sleep on the floor again, but she didn’t. She got very uncomfortable though. She sighed and groaned and wriggled and said her legs were killing her. I felt really sorry for her with her long legs all cramped up, or out in the aisle where people kept kicking them, but not so much when she fell asleep sprawled all over me.

We landed in Singapore and had a wonderful Chinese meal in the airport. I wanted to go into the town (we had to wait three hours) but Gran said, “We’re not allowed, and anyway you wouldn’t like it. It’s the opposite of London, it’s the cleanest city on earth, and if you drop so much as a sweet wrapper they put you in jail and flog you.” Then we flew on to Perth.

I was already in my new clothes. Gran had different taste for me than for her. She’d bought me really cool gear. I was surprised about one thing – it was all casual stuff. She’d said we were going to stay at a hotel, and I supposed that meant dressing up (it didn’t, as it turned out), so what did I need two pairs of combat pants and three pairs of army-looking shorts for? Not to mention all those sleeveless tops.

When we got to Perth I liked it straight away. It was lovely and clean, even without jail and flogging. You could taste the air. The sea was blue and the weather was hot – there were loads of parks and flowers, and gumtrees like in the movies about Australia, that had smooth trunks all patchy green and white, and leaves that smelt like rubbing oil. Some beautiful coloured parrot-things were flying in them.

We checked into a fantastic hotel. I’d never seen anything like it. It was so grand. I had my own room and beautiful bathroom. Gran had the room next door. We unpacked a bit and then had lunch in a big dining room with a buffet. The food! It was unbelievable. Everything you could ever think of to eat, all laid out on silver dishes. Things like baby lobsters. Oysters. Chicken. Duck. Pink roast beef. A zillion salads and hot dishes, and mountains of fruit and cheeses, half of which I’d never seen in my life. There were about ten different kinds of fish. The desserts were like a dream, coloured jellies and flans and creamy cakes and fruit salads like a mass of jewels, and lots more. You helped yourself. You could choose anything you liked, as much as you liked, and come back for more. I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. I think if we’d stayed there for long I would have died, from overeating.

Gran ate oysters till I lost count. I tried one. Yuck! It was like solid snot. She laughed when I said that. She was laughing a lot. Then, just as I was eating my third pudding, something went clunk in my head and I nearly fell asleep right into the whipped cream. Gran saw my eyes closing.

“You’re jet-lagged,” she said. “Come on, sweetness. Bed for you.”

In my room I dropped on to the big double bed. I felt Gran pulling my shoes off. That was all I knew. When I woke up it was dark. I lay awake looking out of the window at the stars. They were so big and clear! After a bit, I fell back to sleep. I felt so happy. England and school were just nowhere. As for Mum and Dad… I pushed them out of my mind. I didn’t want anything to get in the way of having a wonderful time.

Next day everything was a bit crazy. We had breakfast at lunch time, then went for a drive in a cab round the city to see the rich people’s big houses. Then we had a swim in the wonderful blue sea. The beach was great. There were a lot of really fit tanned boys and some of them looked at me in my new bikini, but then they looked at Gran and kept away. But I felt really shy and embarrassed and wished I had a more cover-up cossie. Having a figure is only nice when you’re showing it off to other girls – that’s what I thought, I didn’t like those boys eyeing me up and down.

We went out for dinner to a posh restaurant. It was in a tower that revolved while you ate – you could look at the lights coming on, and the stars shining on the river. They served cooked kangaroo, which Gran ate, but I wouldn’t – I thought it was awful, like eating a horse or a dog. I had steak. I suppose that’s just as bad, really. I fell asleep in the middle. I was really dopey. Gran said it was OK, she was like it herself. She said everyone gets jet lag and that I’d be better in a day or two.

She was right. The next day I felt great. She said tomorrow we were going travelling and I was going to see the outback, like I’d wanted. Of course I thought it would be some kind of day trip. I was so excited. I was loving every minute. I thought Gran was the greatest. She kept hugging and kissing me. She always had, but now I hugged her back. I felt I really loved her, I was just so grateful.

That evening Gran told me she had things to do in the morning, and that I was to pack and meet her in the lobby. “I’m ordering room service to bring you a lovely brekky in your room, then just come on down at ten. Don’t you try to stagger down with your bags, precious,” she said. “I’ll send a bellboy. See ya!” I thought she had a funny smile, as if she had a surprise for me. Boy, did she.

When I came out of the lift next morning, I looked all round this vast lobby, but I couldn’t see her. There was a tall man in a big-brimmed leather hat standing at the reception desk. My eyes went right past, still looking for Gran. Suddenly the tall man turned round. I got a real shock.

It wasn’t a man, it was her! But even facing, I hardly recognised her. She’d changed her clothes. Her clothes? She’d changed everything. She was wearing combat trousers, a khaki shirt, and cowboy boots. She looked completely different. Even her blue hair was covered with the leather hat. She looked like Crocodile Dundee.

I came up to her slowly. “Gran, is it you? What have you done to yourself?”

She laughed, a big boomy laugh. “Well, sugar-puff, we’re off to the bush! You don’t expect me to doll myself up in town clothes for that, do you? Didn’t I tell you there are two of me, a town person and a bushie? This is your bush Glendine!”

While we’d been in Perth we’d driven around in taxis. Now we went outside and waiting at the front of the hotel was one of those truck-things with an open back. Her luggage was piled in that, with a whole lot of other stuff. I thought I saw a sort of iron bed! The bellboy came along with my luggage and put it in with the rest, and helped Gran pull a piece of canvas over everything and tie it down. Gran said, “How d’you like my ute?”

“Ute?”

“Utility. That’s what we call ‘em.”

“Did you say it’s yours?”

“Sure. I’ve had it in a garage while I’ve been in London. They brought it to me this morning and I’ve been off to do a bit of shopping.”

I looked at it. It was about the last kind of vehicle I’d’ve expected her to drive. To begin with I was surprised the doorman let her stand it outside the hotel, it was so rusty and old. It looked as if it might drop to pieces any minute and have to be dragged away.

There was a big metal bar in front.

“That’s a roo bar,” said Gran.

“Rhubarb?”

“No! Roo bar! It’s so if you hit a roo – kangaroo – he doesn’t damage the car. Hitting a roo can cause an awful dent to your ute.”

I said, “Oh, please, don’t hit one, Gran!”

She laughed and said, “They’d better keep out of my way then.”

I soon saw what she meant.

We climbed up into the cabin. The seat covers were so worn the stuffing was coming out. It was a mess inside – big bottles of water everywhere and dangly things in the windows, and rubbish on the floor. I said, “What would they think of this in Singapore?”

Gran let out a kind of whoop of laughter. “They’d beat me to death!” She sounded happier than I’d ever heard her.

Then she just took off.

I’ve never seen anyone drive so fast. Even going through the town, I had to hang on tight. I was breath-stopped and it was only through good luck we weren’t cop-stopped. When we got out on the country roads she zoomed along like someone lit her fuse.

“Gran, slow down!” I yelled.

“No fear, lovie! We’ve got a long way to go!”

Luckily after a bit we got on to a road with almost no traffic. I say “luckily” – it wasn’t really, because then she went faster than ever.

At first there was forest on each side that seemed to go on for ever, but after that was even more for ever with what looked like sheep and wheat farms. It was endless, endless driving. I got sort of hypnotised by the long, dead straight road. Passing another vehicle was an event. There were a few enormous, humungous trucks with two or three containers attached. Gran called them road trains. But there wasn’t much else on the road at all.

Then it changed. On either side were low banks of bright red earth, and trees and bushes, sort of greyish-green, not like English ones. It just went on and on, mile after mile the same. I said to Gran, “Is this it – the bush?”

“Well, you know what they say! The bush is always 50 k on from wherever you are! But I’d call this the beginning of it.”

I said, “I thought it would be more, like, desert.”

“This is a sort of desert. It’s very dry. But it’s full of life. Snakes, goannas, emus… This is roo country. That reminds me, I should slow down now.” And she did. “I have to watch out for them because they’ve got no road sense. They just bound right out on to the road.”

I saw a lot of birds fly up from a lump on the roadside. “Oh, look!” I said, pointing. “Is that a dead one?”

“Yeah. He’s just roadkill now, poor old thing. And that was a wedge-tailed eagle, eating him,” she said, pointing to a huge bird that was flapping away. An eagle! It gave me a kind of shiver of excitement to see a real eagle.

I kept looking for live roos but I didn’t see one. I was glad. I didn’t want one to jump out in front of us and get hit. I saw more dead ones, though, and there were waves of stink in the air.

On and on we drove. At times I thought I might be getting bored, but there was always something new to see. The trees were sort of wonderful. I’d never seen anything like them at home. Gran said, “Pretty well everything here is different from everything anywhere else. It’s because Australia was cut off from the rest of the world, millions of years ago, and different kinds of plants and animals evolved. That’s what makes this such an exciting, wonderful place. Aren’t you glad I brought you?”

Well, I was. At least, I had been, till now. Now we were driving alone through the bush in this clapped-out rusty tin can, which I kind of thought might break down, and Gran had changed. I began to feel just a little bit uneasy. It was pretty obvious we weren’t going back to the hotel that night. Maybe not at all.

After about five hours, when I was stiff and starving, we stopped in a little town. It was so different from Perth! Perth is like any big city (only a lot nicer, certainly than London). This was like something out of an old Western movie, except for all the utes parked along the street instead of horses. The buildings had those funny wooden fronts, and the men walking around looked kind of like cowboys, in a way. Gran parked outside a bar and we went in. I was sure someone would say I was too young, but nobody took any notice. There was hardly anyone in this bar place, and it was dark and dreary. As soon as I walked into it, I wanted to leave, but I needed a pee like mad and by the time I got back Gran’d ordered hamburgers and some Cokes. I counted the cans. Five. I looked around to see if anyone else had joined us.

“Who are all the Cokes for, Gran?”

“One for you, four for me. Or, if you’re really thirsty, two for you and then I’ll have to order another for me.”

I’d never seen anyone drink like she did. She just poured it down as if she didn’t have to swallow. At the end of each can she’d smack her lips and pick up the next.

“What I couldn’t do to a beer!” she said. “But don’t you worry, sweet-pants. I’m just rehydrating myself. I wouldn’t drink and drive.” I didn’t say anything. I knew my dad sometimes had, even though he’d never been stopped. Mum used to totally panic… Of course, that was when we had an old banger. Needless to say, he took it with him when he left us.

We set off again. I asked where we were going. You’ll think it’s about time I thought to ask that, but up till then I’d just been kind of going with the flow. I’d got out of the habit of asking questions.

She shouted above the motor, “Can’t you guess? We’re going to my station.”

I gawped at her. I was thinking railway or tube stations, like, Peckham Rye (ours), or Hammersmith (Nan’s) or Waterloo. “You’ve got a station?”

“Course I have! I told you about it.”

She hadn’t. She had not. She’d never mentioned a station. I’d have remembered.

I’d have asked her to tell me more, but the motor was roaring and I felt too exhausted. The country was more like desert now. There weren’t so many trees, just these low bushes and big tufts of tall grey grass. There wasn’t much to look at, and it was getting hotter and hotter. And dustier. I kept washing the dust out of my throat with one of the big water bottles. At last I fell asleep.

Gran woke me up. It was dark. We must’ve been driving all day.

“Right, Stacey-bell, out you get and help me make a fire.”

I slid out of the cabin and almost fell over a pair of wellies. “Put those on,” said Gran. “And take this torch. There’s lots of wood around. But be sure you kick it before you pick it up.”

“Why?”

“Why d’you think?”

I had no idea why anyone would kick wood. But as I was taking my sandals off to put on the rubber boots, a terrible idea came into my head.

“Gran! Are there snakes around here?”

“There might be. But just remember, the snake that bites you is the one you don’t see, so keep a lookout.”

Oh my God. I nearly fainted. I already said how I hate snakes. I’ve always had a thing about them. I don’t know why because, like I said before, I’d never seen one. They just give me the creeps.

I shot back into the cabin of the ute and sat there shivering with my legs tucked up, imagining loads of snakes coming slithering right up the step and on to the ute floor. Gran came round to my side. “Get out, Stacey,” she said. I think that was the first time she’d called me by my name and not some nickname. And it was the first time I’d heard her use an ordering tone to me. When I still didn’t move, she said, “Don’t be such a pom.”

“What’s a pom?” I asked. My teeth were chattering. Honest to God, they were.

“An English person is a pom. Poms have a bad name with us Aussies for being whingers. I’m not having a whingeing pom for a granddaughter. Now get these boots on your feet and get me some wood or there’ll be no food.”

“I don’t want any. I want to go back to sleep.”

“We’ll make up the beds when we’ve eaten.”

“What beds? I’m not sleeping anywhere near the ground!”

“You’re sleeping in the back of the ute. Nothing can get at you there. Come on, now, hurry up, I’m starving.” When I still didn’t move, she said, “We must make a fire to keep the dingoes away.”

I knew dingoes were wild dogs. Dingoes are fierce. I’ve read about it. They eat babies.

I thought of those movies about African safaris or American cowboys where the campfire keeps wolves and other dangerous animals from coming near. I was so scared, thinking of wild dogs creeping up on us, I almost forgot about snakes. But Gran was just standing there, sort of tapping her foot. I couldn’t just sit there scrunched up all night. I was a bit hungry, come to think of it. And except for the torch, it was pitch dark. A fire would be good. I slowly unscrunched and stuck my feet out. Gran very briskly pushed the wellies on, then pulled me out and put the torch into my hand.

“Go,” she said, turning away.

I shone the torch around and right away I saw some dead wood lying quite close by. I kicked it hard, twice. Nothing popped out. It was a real effort to make myself bend down and snatch up a branch with my finger and thumb. Then I had to walk over to where Gran was digging a sort of pit with a big flat shovel. I shone the torch in front of my boots all the way.

“Here’s a piece,” I said, dangling it.

She stopped and squinted at it as if it was so small she couldn’t see it. “Oh, that’s amazing,” she said. “Do you think you could possibly find me another one just like it? Then we can rub them together and make sparks.”

I dropped the piece and shone my way back to the pile I’d taken it from. I kicked it again. Bit by bit I carried or dragged all the wood from it to where Gran was. She’d pulled up some of the dry grass tufts and before long she’d got a fire going. (Using matches of course. I should’ve known she was having me on.)

The wood was dry and it really burnt a treat. It was weird how much better I felt as soon as it blazed up. She kept me at it till we had a good woodpile – I had to go further than just right next to the ute to get enough. I kept kicking the wood but there were no snakes and after a bit I got so I wasn’t scared to death. I still felt pretty brave though, going off into the dark like that by myself. Once I went about three whole metres from the fire.

By the time Gran was satisfied we had enough wood, there were some hot embers. She scooped them up with the shovel and put them in the pit she’d dug. Then she said, “Now be a love and bring me the Esky.”

I wasn’t really speaking to her at this point, and I felt silly, asking “What’s this” and “What’s that” all the time, so I went to the back of the ute. I’d no idea what an Esky was, but I soon guessed, because what do you put food in if it’s going to be shone on by the sun all day? One of those cold-box things, right? And sure enough there was one. It was dead heavy. I couldn’t get it over the side of the ute so then I noticed there was a kind of catch on the ends of the ute-back. When I slid them, the back fell down with a crash. After that I could drag the Esky off and lug it back to the fire.

Gran opened it and inside were six packages wrapped in foil, along with some milk and tins of Coke. She laid the packets on top of the red embers, then she shovelled more embers on top. The whole thing glowed like an electric stove-plate. She covered the red place with earth and then she got out a thermos and we had some coffee. It was still warm, and sweet. I never drink coffee at home but I drank a big tin mugful.

“That’s your pannikin,” she said. “I’m giving you that. You can even put it on the fire if you want to heat it up.” But I just drank it as it was. The pannikin was pretty, sort of mottled red, and I didn’t want the bottom to get burnt, if it was my present. I reckoned I’d earned it, being brave about the snakes and that, and collecting lots of wood.

Then Gran said, “What’s that blood on your arm?” Later I wished I’d said, “Oh, nothing, it’s just where a dingo bit me,” but I just muttered it was a scratch from a sharp bit of wood. She looked at the cut and said, “Well, a whingeing pom would’ve whinged about that, so good on you.” She squeezed it and said, “Good, there’s no splinters left in there.” Then she got out a jar and started smearing something on the cut.

“What are you putting on it?”

“Honey.”

“Honey!”

“Sure. Didn’t you know honey’s an antibiotic?”

“Why do I need an antibiotic?”

“Because that’s mulga wood and if you get it stuck in your flesh, it’s poisonous.”

My mouth fell open – again. Poisonous wood? Was there anything safe in this place?

The food took quite a while to cook in the embers. At last a really good smell started to come out of the ground. By the time Gran dug the food out I was like dying of hunger. She’d got two plastic chairs off the ute, and a little folding table, two plastic plates, and knives and forks. And some butter and salt. Gran dusted the ashes off the foil and opened the packets. Inside were big chicken legs, baked potatoes, and cobs of sweet corn. We didn’t bother about the knives and forks in the end, we just ate with our fingers by firelight. It tasted well delicious. I drank Coke and she drank beer. Then she stood up and stretched and said, “Right. Bed.”

She made me close the Esky and pack all the stuff away in a box. I thought I’d better burn the chicken bones in case they brought the dingoes. The fire was dying down. Nearly all my wood was gone. I said, “Who’s going to keep the fire going?”

She said, “Well it’s no use looking at Glendine. She’s going to make big Zs.”

I said, “But if we don’t, the dingoes’ll come!”

She said, “You’re an easy mark, Stacey. There’s no dingoes around here. Now help me with my bed.”

I didn’t say anything. I helped her lift a rusty old iron bed with fold-back legs and a mattress off the back of the ute, and she set it up. It wasn’t far off the ground… There was another mattress left on the floor of the ute for me. Then she untied two bundles.

“Here’s your swag,” she said. A swag turned out to be a sleeping bag. She had a pillow for me, too. She made up her own bed with another swag. I said, “I need to go to the loo.” I know I sounded sulky. I couldn’t believe it about the dingoes, that she’d do that just to make me get out and help.

She picked up the shovel and the torch. “Go ahead,” she said. “Over there, by those trees. Keep downwind, ha ha.”

I stared at the shovel, thinking what it meant. I had to dig a hole, and— No. It was too gross. Though how else? We were a million miles from anywhere. It looked to me like even the trees were about a hundred miles away from the little circle of firelight where the ute was. Where Gran was.

“Was it true about the snakes?” I said.

“Lovie, would I lie to you? Of course there are snakes in the outback. Just keep shining the torch and stay where the ground’s open. Oh, here’s some dunny paper. Be sure to bury it, too. Now go on and do what you have to do.”

Grandpa used to say, “Needs must, when the devil drives.” So I did it. I managed somehow. But the walk there into the darkness was the worst thing I’d ever done, even worse than when our diving teacher made us dive into the school pool over her arm the first time.

I was beginning to change my mind about Gran being the greatest. That’s putting it nicely.