Читать книгу Michael Morpurgo: War Child to War Horse - Maggie Fergusson, Maggie Fergusson - Страница 13

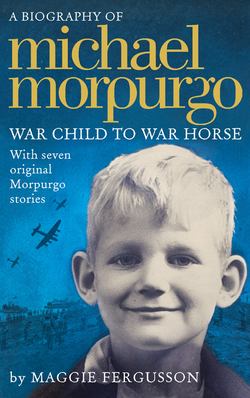

Pieter and Michael, 1948.

ОглавлениеBut most vivid of all are his memories of bedtime, when Kippe would sit at the end of his bed and read to him. She read from Aesop’s Fables, and from poets such as Masefield and de la Mare, from Belloc, Lear and from Kipling’s Just So Stories. She had a way of making imaginary characters and places come alive, of conveying the music and joy and taste of language:

Then Kolokolo Bird said, with a mournful cry, ‘Go to the banks of the great grey-green, greasy Limpopo River, all set about with fever-trees …’

Michael rolled the words around on his tongue like sweets. When he was three, his mother found him rocking to and fro in his bed, chanting, ‘Zanzibar! Zanzibar! Marzipan! Zanzibar!’

Story-time over, Kippe would leave the door slightly ajar to let in a chink of light. The smell of her face powder lingered in the room.

Sometimes there could be about Kippe an almost reckless joyfulness. When one afternoon Pieter and Michael locked themselves into their fifth-floor bedroom while they were supposed to be resting, she shinned undaunted up a drainpipe, ignoring Jack’s protests, and climbed in through their window to rescue them. When visitors came to the house she shone. ‘As she opened the front door,’ Michael remembers, ‘it was as if she was walking on to a stage – beautifully dressed and made-up, charming, sparkling.’

But when the visitors left she tended to collapse, reaching for her cigarettes and smoking almost obsessively. And sometimes for days on end a sadness – what Pieter calls ‘a wondering’ – would settle upon her, and she became quiet and unreachable. Twice a year she would take Pieter and Michael on a bus to Twickenham to visit Tony’s parents in their neat, modest, semi-detached house in Poulett Gardens. Michael remembers the uncomfortable formality of these visits – ‘the scones, the clinking of spoons on teacups’ – and the awkwardness as the conversation turned to Tony, his grandparents bringing out photographs and press clippings to show to the boys. On the way home, and for days afterwards, Kippe was silent. Michael knew that to ask questions would upset her further, so he too remained silent, aware simply that ‘ours was a family which had at its heart a tension’.

In the wider world, too, he was becoming aware of complexity and shadows. The area around Philbeach Gardens had been heavily bombed in the Blitz, and the house next to number 84 completely destroyed. The cordoned-off bomb site was reachable via the cellar, and Michael particularly liked to play here alone. ‘It was my Wendy house, I suppose. A rather tragic Wendy house.’ Among the weeds and crumbling walls were remnants of life – bits of cutlery, a chair, an iron bedstead – evidence that in the very recent past ‘there had been this terrible trauma’ for the family that had lived there.