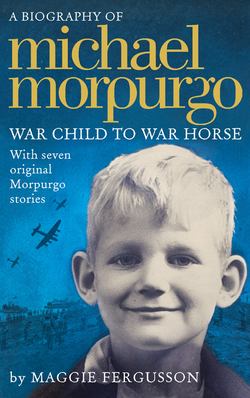

Читать книгу Michael Morpurgo: War Child to War Horse - Maggie Fergusson, Maggie Fergusson - Страница 6

Оглавление

Where to begin, when telling the story of a writer’s life?

Perhaps simply with the moment of his birth. Michael Morpurgo, then, was born on 5 October 1943, at the height of the Second World War.

On the morning of his birth The Times announced that Corsica had fallen to the French Resistance – the first department of France to be liberated. In the days that followed it became clear that the Allies had the Germans on the run. On 7 October the Red Army mounted a new thrust on enemy positions along the River Dnieper, breaking the Germans’ 1,300-mile defence front; a week later Italy declared war on Germany. By the end of the month the Allies were bombing the Reich from Italian soil. In early December the British government announced that there would only be enough turkeys for one in ten families at Christmas, but any sense of joylessness was eased, on Boxing Day, by the news that the British navy had sunk the last of the great German battleships, the Scharnhorst, off the coast of Norway.

War has been a constant presence in Michael’s stories. And it is significant, as you will see in the story Michael has written to end this section of the book, that he was a child at a time when the war was just over, yet when its influence was still keenly felt and seen.

But if you want to understand the threads of Michael’s work – the ingredients that combined to make him a storyteller and performer – you need to start earlier, with his family. You see, Michael comes from theatrical roots, something which won’t surprise anyone who has seen him talk about his books on stage. For generations, theatre and stories have been part of the fabric of his family’s life.

Michael’s grandmother, Tita, was a large, imposing woman who gave Michael his first inklings ‘of what God might be like’. Before her marriage she had been a Shakespearean actress. She had a voice so deep and tremendous that she was often given men’s parts. Her mother, Marie Brema, had been a professional opera singer, who was once summoned to Buckingham Palace to sing for Queen Victoria.

Neither Tita nor her mother had their heads turned by success. Both believed deeply in Christian charity and most of the money they made on stage was poured into Brema Looms, a workshop providing employment for crippled girls from London’s East End.

In 1906 Tita, who in her late twenties had never so much as kissed a man, had met and fallen in love with a Belgian poet, scholar and nationalist, Emile Cammaerts. There were differences between them. Emile spoke very little English, and was an atheist. Tita set about tackling both problems with great forcefulness.

And she succeeded. A Belgian woman was engaged to teach Emile English (they began their lessons by teasing out Othello, line by line) so that by the time he and Tita were married in 1908 his English was fluent. He had also converted to Christianity with a zeal that would never leave him. As there was little prospect of Tita’s pursuing her stage career in Belgium, and as she felt she must look after her mother, they settled in London, before moving, as their family grew, to Radlett – a village in Hertfordshire.

Tall, and with a fine, monumental head, Emile Cammaerts became revered in academic and literary circles both for his intellect and for his passionate devotion to Belgium. Invalided out of the First World War with a weak heart, he threw his energies instead into composing fiery, defiant, patriotic poems to encourage his compatriots. He was Belgium’s equivalent of Rupert Brooke, the famous British poet of the First World War.

So patriotic was Emile, in fact, that when his fourth child’s birth coincided with a significant Belgian victory over the Germans, he named her after the hamlet, De Kippe, where this had taken place. This daughter, Kippe, would grow up to become Michael’s mother, and an actor like her mother.

To Michael, as a small boy, Emile Cammaerts seemed ‘all that a grandfather should be’. He had a flowing beard, thick tweed suits and heavy brown shoes. He emanated jollity. His theme tunes, in Michael’s memories, are Mozart’s horn concertos, to which he would bounce his grandchildren on his knee; and he had about him what his Times obituary would describe as an air of ‘enchanted innocence’. Though he had made his career as an academic, his earliest published works had been plays for children, and he had written a study of nonsense verse. He would delight Michael with recitals of ‘The Owl and the Pussy-cat’, ‘The Dong with a Luminous Nose’ and, most memorably,