Читать книгу The Quest for the Irish Celt - Mairéad Carew - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

‘IRELAND BELONGS TO THE WORLD’: CELTIC ORIGINS, ANTHROPOLOGY AND EUGENICS

We believe that the mysticism, artistry, and other peculiar gifts of the modern Irish can be understood only by fitting their prehistory into their modern civilization, and by establishing the continuity of their ancient culture in their life of today.1

– Earnest A. Hooton

Why should Harvard University concern itself with Ireland?

In 1937, R.A.S. Macalister posed the pertinent question ‘Why should Harvard University thus concern itself with Ireland?’2 The reasons why the Harvard Mission came to Ireland and the political ideology underpinning its archaeological work was dominated by eugenic and racialist concerns.3 This work fitted easily with Irish nationalist aspirations for a proven scientific Celtic identity. The academic framework which was used for interpretative purposes and the academic backgrounds of the protagonists helps to explain how and why particular results were obtained about the Celtic race. Macalister believed that the answer to his question on the reasons for Harvard concerning itself with a study of the Irish was ‘the fact that Ireland belongs to the world’. He wrote that:

Here, at the remote end of Europe, but little disturbed by the stream of Time which tore the rest of the Continent to pieces over and over again, Ireland went on in her own old way, and kept alive primeval cultures, arts, beliefs, which were elsewhere submerged. Only in Ireland can we get down to the foundations upon which European civilisation is based; and as the whole world is interested in European civilisation, the whole world calls upon Ireland to solve problems that can be solved nowhere else.4

Macalister was probably referring in an oblique way to the problematic issues associated with the mixing of races, which were being debated around the world in the 1920s and 1930s. Themes of cultural and racial purity were expressed through the disciplines of archaeology and anthropology and were an essential part of a cultural vision reflecting the ‘underlying affinity between anthropology and modernism’.5

The Harvard Archaeological Mission was organised and managed by Earnest A. Hooton and was under the direction of an executive committee of the Division of Anthropology of Harvard University. The members of this committee included Hooton, Alfred Marston Tozzer and Roland Burrage Dixon. Tozzer served as Director of the International School of American Archaeology in Mexico from 1914 and was appointed chair of the Department of Anthropology at Harvard in 1921. He also became a faculty member of the Department of Sociology at Harvard in 1930. In 1946, he was appointed John E. Hudson Professor of Archaeology at Harvard.6 Roland Burrage Dixon formed ‘an integral part of the archaeological heritage of the Peabody Museum’ at Harvard.7 He made significant contributions and publications in the fields of archaeology, linguistics, physical anthropology and sociocultural anthropology, eventually becoming a professor of anthropology at Harvard in 1916.8 He also had an interest in folklore and served as the Secretary-Treasurer of the Harvard Folk-Lore Club (founded 1894).9 Among Dixon’s important books was The Racial History of Man, published in New York in 1923.

One of the reasons that Ireland was selected for a co-operative study by social and biological scientists from the Division of Anthropology of Harvard University was that it was ‘politically new but culturally old’ and that it was ‘the country of origin of more than one-fifth of the population of the United States’. The Harvard team proposed to investigate the social, political, economic and industrial institutions in Ireland and to examine the Irish people. Their physical characteristics would be measured to determine their ‘racial affinities’.10 Excavations would be carried out in an effort to connect prehistoric cultures with early historic and modern Irish civilisation. The relationship of social and material culture to race and environment would be analysed.

The Harvard Mission and Eugenics

Another reason, cited by Hooton, for choosing Ireland for the Harvard survey was because the Celtic language was ‘an archaic Aryan language’.11 For an emerging European, independent nation-state prior to the Second World War, being identified as a white European Celt (possibly an offshoot of the Aryan race) was economically and culturally advantageous. Cultural imperialism was also associated with biological determinism during this period.

Hooton was a member of the American Eugenics Society (AES) and served as Chairman of the Sub-Committee on Anthropometry. The AES was founded a year after the Second International Conference on Eugenics which was held in New York in 1921. Among the founders were the ‘premier racial theorist’ Madison Grant, Vice-President of the Immigration Restriction League and author of The Passing of the Great Race: Or the Racial Basis of European History published in New York in 1918; and the ‘doyen of American archaeology’, Henry Fairfield Osborn, who penned the preface to Grant’s book. The AES became the ‘key advocacy and propaganda wing of the Eugenics movement’.12 The advisory council of this society included William Welch, the Rockefeller Foundation’s medical director.13 The Rockefeller Foundation funded medical research in Ireland and in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s. It also funded various anthropological surveys, including the work of the Harvard Mission to Ireland. Practical social problems relating to race and immigration influenced the focus of American anthropology in the 1920s and this was reflected in the interest of the National Research Council and the Social Science Research Council in such projects.14 In the 1930s biological determinism in anthropology was hotly debated in academic circles. This followed the Social Darwinian ideas and eugenic discourse on race prevalent at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century in America and Europe. In the nineteenth century, inferiority based on racial classification was used to justify colonialism, slavery and dispossession. A similar classification through the medium of physical anthropology in the 1920s and 1930s could be used to justify harsh immigration laws in the United States, discrimination and segregation laws.

One of the aims of the American eugenics movement was to ‘create an American eugenic presence throughout the world’. To this end a ‘network of eugenic investigators’ was installed in Belgium, Great Britain, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Czechoslovakia, Italy, Holland, Poland, Germany and the Irish Free State. Potential immigrants to the United States were ‘eugenically inspected’.15 This ideology drove the Harvard Mission to Ireland. Hooton stated that the purpose of the physical anthropological work conducted in Ireland, which involved measuring and observing the bodily features of thousands of Irish men and women, was ‘to determine their racial affinities and their constitutional proclivities’.16 At that time it was believed that proclivities for drunkenness, criminality, laziness or other socially deviant behaviour could be ascertained through the examination of physical attributes. Equally, more positive attributes of those deemed to be superior races could be ascertained.

Edwin Black claims in his book War Against the Weak Eugenics and America’s Campaign to Create a Master Race, that the AES supported Germany’s eugenic programme.17 However, Hooton was staunchly anti-Nazi in his writings in the late 1930s.18 Hooton, it seems, could not see the inherent paradoxes in his own beliefs and wrote of his disapproval of Nazi distortion of anthropological ideas:

There is a rapidly growing aspect of Physical Anthropology which is nothing less than a malignancy. Unless it is excised, it will destroy the science. I refer to the perversion of racial studies, and of the investigation of human heredity to political uses and to class advantage. Man has long sought to excuse his disregard of others’ rights by alleging certain biological differences which determine the superiority of his own race or nationality and the inferiority of others. The allegation of racial superiority or inferiority previously dismissed as a mere sophistry now assumes the nature of a valid reason for wholesale acts of injustice.19

Hooton’s apparently contradictory views on race and eugenics were commonplace at that time. He was appalled at the ‘national sadism and sheer suicidal lunacy as impels the present German government to destroy that minority element which has been responsible for some of its most brilliant cultural achievements’.20 Christopher Hale described Hooton as ‘a fervent eugenicist’ and a ‘disciple of the Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso’ who had ‘disliked blacks and Jews’.21 Hooton was disciplined by the President of Harvard for his ‘inhuman’ teachings.22 However, despite being a eugenicist who advocated better breeding for the human race and the removal of those deemed unfit for human society such as the disabled, the insane, the criminal and the economically unviable, Hooton was not overtly racist in the sense that he believed that the unfit from all races, including the white race, should be removed from society. He proposed the establishing of ‘an America national breeding bureau that would determine who could reproduce with whom’.23 It was no coincidence, however, that in America, those who fitted many eugenic categories also fitted the category of poor immigrants including ‘Negroid’, Italian, Mexican and poor rural Americans. Indeed Black’s definition of the eugenic movement was ‘It was a movement against non-Nordics regardless of their skin color, language or national origin’.24 Germany’s eugenic programme was getting a very bad press by the late 1930s in the United States.25 Prior to that there was much support for Hitler among eugenic societies and in universities. A Nazi eugenics exhibit, organised by the Deutsches Hygiene Museum in Dresden, was shown across American between the years 1934 and 1943. It was sponsored by the American Public Health Association. It was hoped that it would ‘make the case that eugenics provided an economically viable and scientifically valid alternative to the social welfare programs initiated by Franklin D. Roosevelt’.26 Roosevelt’s New Deal included unemployment schemes for archaeological research which, in turn, influenced a similar scheme in Ireland. (See Chapter 7)

The Study of the Celts in Ireland

The quest for the recovery of scientific evidence for the long-headed Celt and ancestor of the European white man was pursued by Hooton through the work of the Harvard Mission. By the time the American academics arrived in Ireland in 1932 to study the Celtic race, using new archaeological science and physical anthropology, academic interest in Celtic origins and identity was well established. While the idea of a Celtic race was fixed in literature, attempts were made initially in the nineteenth century to classify it scientifically. The inhabitants of the Aran Islands were a case in point. They were deemed to be primitive and therefore an uncontaminated race. The traditional belief was that the Aran islanders were descended from the Celts. Samuel Ferguson had written about them in 1852: ‘If any portion of the existing population of Ireland can with propriety be termed Celts, they are this race’.27 William Wilde, the polymath, eye-surgeon, archaeologist and father of Oscar, led the Ethnological Section of the British Association to Aran in 1857.28 The famous archaeologist, George Petrie, was also interested in the islands and wrote that ‘In the Island of Innishmain alone, then, the character of the Aran islander has hitherto wholly escaped contamination, and there it still retains all its delightful pristine purity’.29 The so-called purity of race and culture of the inhabitants were viewed in nationalistic terms by some writers and was described by Scott Ashley as follows:

The Aran Islands were being invented as bastions of the ancient sublime, so the islanders themselves were endowed with nationalist and racial significance. They were modern primitives, insulated from the deadening hand of progress and Anglicization, true Irishmen and women, models for an Ireland freed from British dominion. They were a pure Gaelic stock uncorrupted by infusions of degenerate blood from the mainland; they were perhaps, the last true descendants of the Fir-Bolgs, the primeval inhabitants of Ireland.30

A.C. Haddon and Dr C.R. Browne, who carried out a scientific survey of the Aran Islanders in 1892, were also influenced by the work of J.T. O’Flaherty who published ‘A Sketch of the History and Antiquities of the Southern Islands of Aran, lying off the West Coast of Ireland; with Observations on the Religion of the Celtic Nations, Pagan Monuments of the early Irish, Druidic Rites, & Co’ in Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy for 1825. O’Flaherty in his paper asserted that ‘In no part of the Celtic regions are the Celtic habits, feelings, and language better preserved than in the southern Isles of Aran’.31 Like other nineteenth-century romantics writers, he believed that Aran was a microcosm of Ireland which in turn was a microcosm of Celtic Europe. He pointed out that Gaul, Spain, Britain and the other Celtic States had lost all their records of remote antiquity but that Ireland had preserved historic evidence ‘illustrative not only of her own antiquities, but, in a great measure, of those of Europe’.32 The Aran Islands survey was carried out by the Anthropometric Committee of the Royal Irish Academy. A study of the ethnography of the Aran Islands was to be the first in the series of such studies to be undertaken around the country by the committee. The emphasis was on the routine observations made in the Anthropometric Laboratory and in researches in country districts.

Eoin MacNeill got his own anthropometric chart completed at the Dublin Anthropometric Laboratory in the Museum of Comparative Anatomy, Trinity College Dublin.33 It was dated 11 February 1893 and signed by Professor A.C. Haddon. Haddon, described by H.J. Fleure as ‘a pioneer of modern anthropology’, and a ‘keen and vigorous evolutionist’ was a demonstrator in zoology at Cambridge from 1879 until he left his position to take up a Professorship at the Royal College of Science in Dublin in 1880.34 Haddon co-founded the Anthropometric Laboratory at Trinity College which was modelled on the London Laboratory of Francis Galton, a cousin of Charles Darwin’s. Galton set up his laboratory in 1884, a year after he had first coined the term ‘eugenics’. The aim of the work conducted at the Dublin Anthropometric Laboratory was to gain an ‘understanding [of] the racial characteristics of the Irish people’.35 Haddon and Browne expressed the opinion that ‘the ethnical characteristics of a people are to be found in their arts, habits, language, and beliefs as well as in their physical characters’.36 However, this survey was not undertaken under the auspices of any specific eugenics society even though the direction of the research had eugenic overtones. There was no eugenics society established in Dublin but one was set up in Belfast in 1911, and eugenic ideas permeated the social sciences of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century in Ireland.37

Race could be scientised by categorising it using instruments of measurement common in physical anthropology.38 There was in turn the scientising of social status by correlating it with race. The methods employed in the examination of the physical characteristics of the Aran natives were based on those employed by John Beddoe, outlined in his influential book, The Races of Britain, published in 1885. Beddoe had paid a visit to Inis Mór in 1861. Haddon and Browne also made use of Beddoe’s ‘Index of Nigresence’ which worked out the degree of prognathism (protrusion of the lower jaw) of each skull. John Messenger described the conflicting results between literary and scientific interpretations of cultural reality in the Aran Islands. One of the reasons for this, he argued, was primitivism, a type of utopianism and nativism which was influenced by nationalism. This led to beliefs about the Aran Islanders which ‘run counter to scientific opinion’ and included the idea that they were ‘direct descendants of Celts;’ that the Irish were a ‘pure Celtic race’ and that ‘Celtic civilization developed long before and was superior to Greek and Roman civilizations’.39 The racial aspect of Celtic identity was expounded by Douglas Hyde in his 1893 speech, ‘The Necessity for de-Anglicising Ireland’: ‘We must strive to cultivate everything that is most racial, most smacking of the soil, most Gaelic, most Irish, because in spite of the little admixture of Saxon blood in the north-east corner, this island is and will ever remain Celtic at the core’.40 Eoin MacNeill developed this idea, writing in 1921 that: ‘In ancient Ireland alone we find the autobiography of a people of European white men who come into history not moulded into the mould of the complex East nor forced to accept the law of imperial Rome’.41 The previous year, de Valera, during his fundraising tour of the United States, attempted to get political recognition for the Irish Republic by arguing that ‘Ireland is now the last white nation that is deprived of its liberty’.42

Macalister asserted in 1927 that Ireland and Scandinavia were the most important European countries to the ethnologist and social historian because ‘all the rest have been forced into a Roman mould which has distorted or destroyed the native institutions’.43 When Eoin MacNeill published Celtic Ireland in 1921, the author had clearly accepted the premise that Ireland was indeed a Celtic country, explaining that he had ‘sought to establish the foundations of our early historical polity on a supposed Celtic colonisation coincident with the Roman conquest of Britain. 44 MacNeill was wary of the misuse of historical sources for political reasons and warned that ‘superficial methods of expounding history are perhaps the main cause of modern race-delusions’.45 As archaeology was interpreted as scientific evidence for historical events, MacNeill was satisfied that Macalister, whom he described as ‘the highest Irish archaeological authority’, believed that the Celtic colonisation of Britain and Ireland began in the Late Celtic or La Tène Period of the Iron Age.46 Macalister expressed the view in an address delivered to the RIA in 1927 that ‘on the current, and most probable, hypothesis, the Celtic culture was introduced into this country by a body of invaders – or, rather, a succession of invaders – who came at some time during the course of the European Iron Age’.47

Archaeology as a discipline is intimately connected with the political and social context in which it is interpreted. The author of the interpretation is invariably influenced by his/her own social background and education. As Christopher Evans explained it, ‘the practice of archaeology is never divorced from its times’.48 Macalister, for example, was of the view that the putative invaders of Ireland abstained from intermarriage with the natives and that: ‘The fair-complexioned and the dark-complexioned people are rigorously kept apart: the former are the aristocrats, with the attributes, physical and mental, of nobility, while the latter are the serfs’.49 Macalister’s idea of aristocrats and serfs is an observation based more on social prejudice than scientific fact. Macalister wrote in his book Ireland in Pre-Celtic Times (1921) that there was evidence for two stocks in Ireland ‘separated from one another by social position running parallel with racial character’.50 This correlation between race and social position was a common eugenic notion. Greta Jones has described how eugenic societies ‘showed a clear bias toward seeing eugenic worth as reflected in superior social status’.51 In the United States there was also a belief in the eugenic superiority of the North European.52 Macalister’s belief that ‘the distinction was maintained by obstacles to intermarriage’ may reflect the global debates about miscegenation that were current in the 1920s. He was also of the opinion ‘that the ruling classes were an importation, a tribe of conquerers, who had subdued and reduced the original inhabitants to a subordinate position, if not to actual serfdom’.53 This view reflected the nineteenth-century colonialist attitude of archaeologists to wards human progress. Macalister was aware of the problems associated with the issue of race in physical anthropological surveys, noting that ‘Mankind is scientifically divided into races, a term too often misused’.54 He defined race as follows:

It must be clearly understood that Race depends simply and solely on physical characteristics, and on psychical and temperamental idiosyncrasies: the peculiarities with which a man is born. It has nothing to do with religion, language, political and social connexions or sympathies, or with any other of the peculiarities which a man acquires from his environment as he grows up.55

Macalister and Eugenics

Race was integral to nineteenth-century archaeological scholarship and continued to be important in the twentieth century, particularly in the interwar period. The 1930’s Harvard eugenic survey of the Celtic/Irish race side by side with the archaeological study of human remains was an example of this. In his address to the Royal Irish Academy in 1927 Macalister had expressed the view that ‘there is the greatest need’ for an Anthropological Committee, commenting that ‘there are few countries in the world of whose ethnology we know less than we do of Ireland’.56 He had also observed in his book, Ireland in Pre-Celtic Times, that ‘the subject of Irish craniology, both ancient and modern, is as yet an almost untilled field’.57 He was familiar with the physical anthropologist’s use of the cephalic index which was used to determine skull type and explained the cephalic index as a figure which ‘expresses the breadth of the head as a percentage of the length’.58 A Swedish professor of anatomy, Anders Retzius, was first to use the cephalic index in physical anthropology in the nineteenth century, to classify ancient human remains found in Europe. He classified brains into three main categories, ‘dolichocephalic’ which were long and thin, ‘brachycephalic’ which were short and broad and ‘mesocephalic’ which were of intermediate length and width. These ideas were later used by the eugenic theorist Georges Vacher de Lapouge who in L’Aryan et Son Role Social (1899) divided humans into hierarchical races with the Aryan white dolichocephalic at the top.

It was Macalister’s opinion that these physical measurements of Irish skeletons showed that the Bronze Age culture was introduced into Ireland by trade and not by conquest or invasion and that, ‘until the process of contamination began after the Anglo-Norman conquest, no brachycephalic race found a footing in the country’.59 Similar classifications had been used by the American anthropologist William Z. Ripley in The Races of Europe in 1899. Ripley’s book was rewritten in 1939 by Carleton S. Coon, a student of Hooton’s.60 Coon believed that Caucasians had followed a separate evolutionary path from other humans and that the earliest Homo Sapiens were long-headed white men. Coon attempted to use Darwinian adaptation to explain the physical characteristics of race.61

Macalister expressed disappointment that the study of the Irish race was hampered by the limited amount of skeletons available for examination. This was because most of the burials found were cremations. There was also the problem of excavations being carried out ‘either by ignorant labourers dreaming of treasure, or by equally ignorant and far more reprehensible collectors, in search of curiosities for their cabinets’.62 The main collection available for study was a number of crania dug up from a ‘charnel mound’ near Donnybrook in south Dublin in 1880.63 Other than this collection Macalister acknowledged that he could ‘discover nothing but isolated measurements of individual bones, scattered through books and the proceedings of societies’.64 Despite this lack of evidence he concluded that the results showed that ‘the pre-Norman population of Ireland was dolichocephalic, this belonging either to the Nordic or the Mediterranean Race.’65 In a supplementary examination of descriptions from the literature, Macalister deducted from a section which he selected specifically for the purpose that ‘all persons of importance native to Ireland are described as having golden hair’ and that ‘there is evidence that the superior classes had light-coloured eyes’.66 He acknowledged that this assertion was made despite the fact that while measurements of stature and of head-shape can be obtained from skeletons ‘the test of coloration cannot be applied except to a living person’.67 He was very much in favour of this new anthropological approach to Irish archaeology.

Ireland as a Microcosm of Celtic Europe

The notion of Ireland as a microcosm of Celtic Europe was explored by the Harvard Mission. The Aran Islands Survey itself could be seen as the precursor, in microcosm, of the Harvard Mission project with its three-stranded approach to the study of the Irish Celt. Apart from the difference in scale there was also a difference in political and cultural perspective. Haddon and Browne fused the old colonialist approach of a study of exotic natives on tiny secluded islands with the increasingly nationalistic outlook of the Royal Irish Academy. Previous work such as that by Beddoe reflects a nineteenth century colonialist perspective and the use of anthropology as an instrument of government information to control inferior, subject races. Liam S. Gogan, Assistant Keeper of Irish Antiquities at the National Museum of Ireland, dismissed Beddoe in 1933 as ‘that old fool Beddoe who for the satisfaction of Victorian Britain demonstrated that a large section of our population was negroid’.68 The idea of the Celt in the 1930s was that of a noble, tall, blue-eyed and fair-haired warrior. The Harvard Mission represented an Irish-American rediscovery of the noble Celt of antiquity, which had a European and global resonance. In his privately published memoir Hugh O’Neill Hencken remembered Hooton saying to him ‘I think the Department should do something about Ireland and I think the Boston Irish would support it’.69 Wealthy Irish-Americans contributed to the funding of the project.70

The American Anthropologists and their Theoretical Framework

An understanding of the intellectual background and politics of the Harvard anthropologists is essential to the academic framework and the political context within which the Harvard Mission carried out its work. Hooton is best known for his anthropological work on human evolution, racial differentiation, the description and classification of human populations and criminal behaviour.71 He believed that ‘Physical anthropology is properly the working mate of cultural anthropology’ and in turn physical anthropology was ‘the hand-maiden of human anatomy’.72 A biological determinist, Hooton expressed admiration for the work of scholars engaged in scientific racism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.73 He obtained a PhD in Classics at Harvard in 1911 and went to study under Sir Arthur Keith while he was on a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford. There, he developed his interest in human palaeontology and in particular palaeoanthropic fossils from England and Europe. He also studied classical archaeology, Iron Age and Viking archaeology and was involved in the excavation of Viking boat burials. In 1912 he took a diploma in anthropology under R.R. Marrett, an ethnologist who had established a Department of Social Anthropology at Oxford in 1914.74 In 1913, Marrett had helped Hooton to get a job as an instructor in anthropology at Harvard. It was noted in Life Magazine in 1939 that Marrett was one of the men at Oxford ‘who helped to mold Earnest Albert Hooton into what Hooton is today’.75 Before he embarked on his work in Ireland Hooton had gained extensive professional experience in organising large surveys, training personnel for field work, and the analysis of results obtained.76 During the 1930s he organised large-scale anthropometric surveys of human beings – students attending Harvard University and attendees at the Chicago and New York World Fairs.77 His statistical laboratory was located over the Peabody Museum at Harvard. The bone lab, over which he presided, held extensive collections of human skeletons from all over the world. For thirty years between 1920 and 1950 he was eminent in American anthropology and many students of physical anthropology came under his influence. This ultimately changed the composition of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists.78

In the 1930s American anthropology came under the influence of British anthropologists who espoused theories of functionalism. This idea was that all structures and institutions of a social group work in a sort of physiological manner and to understand society the functional relationship of its component parts need to be understood.79 Those most associated with this school were the Cambridge anthropologists, A.R. Radcliffe-Brown who spent six years at Chicago and Bronislaw Malinowski who spent three years at Yale. Lloyd Warner, who was responsible for the social anthropological strand of the Harvard Mission’s work in Ireland, came under Radcliffe-Brown’s influence and was himself influential at Harvard in the early 1930s.80 At Cambridge in the 1930s the functionalist school of anthropologists, under Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown, wished to remove themselves from the discipline of archaeology because that discipline had more in common with history. Malinowski believed that anthropology needed to discard ‘the purely antiquarian associations with archaeology and even pre-history’.81 Radcliffe-Brown was of the opinion that archaeology had a natural affinity with history.82 Hooton’s view was that ‘archaeology shares with history the function of interpreting the present through knowledge of the past’.83

Warner wanted to design a research framework which allowed the researcher to see ‘society as a total system of interdependent, inter-related statuses’.84 At that time Warner was working as a tutor and instructor in the Anthropology Division of Harvard University where he was an Assistant Professor of Social Anthropology. He had carried out extensive studies in the social anthropology of primitive peoples and directed a survey of the social structure and functioning of a large New England town. He had previously carried out fieldwork among the Aborigines in Australia. He was also collaborating in anthropological research in the industrial field with the Harvard School of Business Administration. His job in Ireland was to participate in the sociological field work and to personally train and supervise the workers.85

Warner’s ideas reflect Hooton’s understanding that: ‘The function of the anthropologist is to interpret man in his entirety – not piecemeal’.86 Warner sought to study communities in the New World rather than in exotic locations. He was instrumental in bringing to American anthropology the ideas of the social scientist, Emile Durkheim.87 Hooton’s difficulty with social anthropology was that ‘they wilfully abstract social phenomena and divorce man’s activities as a social animal from man himself’. He believed that it was possible ‘to predict from the physical type of racial hybrid his occupational, educational, and social status’.88 This reflected his own view that biology was the main predictor of man’s place in the world and not environment or education. This idea is the essence of scientific racism. According to Stocking this ‘scientizing trend’ in American anthropology during the 1930s was a ‘renewal of Morganian tradition’.89 Lewis Henry Morgan was a lawyer, statesman and ethnologist who earned himself the title ‘Father of American Anthropology’ for his scientific work on social anthropology, which was heavily influenced by the ideas of Darwin.90 In 1875 he was responsible for forming the section of anthropology in the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The physical anthropological expedition was the last strand of the Harvard Mission to start work in Ireland. At first it consisted of only one man, C.W. Dupertuis, who was an advanced student of Physical Anthropology at Harvard. In his lecture to the Experimental Science Association of Dublin University on 26 February 1935 entitled ‘Notes and Observations of Recent Anthropometric Investigations’, Dupertuis explained that for the first time in history an attempt had been made to make a racial survey of the population of a whole country. In an Irish Times article the following day it was reported that Dupertuis believed that the survey ‘would go a long way towards clearing up the racial problems of Europe’. The reasons given for the expression of this eugenic ideal were as follows:

Ireland being more or less an isolated country, was probably not so mixed racially as Continental countries, and he [Dupertuis] felt that in certain parts of this country the descendants of more or less pure racial types which came in from across the waters would be found. He hoped to be able, at the end of the survey, to answer such questions as who were the Celts, and what was their racial type or types, and what element in the present day population represented the descendants of the earliest inhabitants of this island and just where they were to be found today.91

Dupertuis spent a lot of time in many districts of Ireland and grants were put at his disposal by the Irish Free State Government to help him during the later stages of his work. He already had two years of experience in anthropometry at the Century of Progress International Exposition, 1933–4, in Chicago, where he organised the Harvard Anthropometric Laboratory, which measured and observed visitors to the fair. After the first year of anthropometric work in Ireland Dupertuis returned to America. The following year he came back to Ireland accompanied by his wife, Helen Dawson. She worked as his recorder and collaborator in the Irish survey. She held a National Research Council Fellowship in Anthropology and used this to study Irish women of the West Coast. She collected an anthropometric sample of some 1,800 women for analysis in an effort to establish the characteristics of the Celtic race.92

Hooton acknowledged that Seosamh Ó Néill, Secretary of the Department of Education for the Irish Free State was very cooperative with the physical survey of the Harvard Mission. Ó Néill was instrumental in coaxing members of his and other government departments to submit themselves to an anthropometric examination. He was also responsible for administrating the grant of £40 given by the Government for the work towards defraying of expenses incurred during the collection of data.93 De Valera not only manifested keen interest in the anthropometric survey, but also offered helpful suggestions, and Sir Richard Dawson Bates, the Home Secretary for Northern Ireland, also gave his official sanction to the work there.94 Dupertuis interviewed Major-General W.R.E. Murphy, the Deputy Commissioner of the Garda Síochána, who agreed to provide letters of introduction to the superintendents of the Civic Guard in various parts of the country. This was approved by the Commissioner of the Garda Síochána, Colonel Éamon Broy. The Gardaí therefore became, ‘active co-workers in the gathering of anthropometric material’. The cooperation of the Royal Ulster Constabulary of Northern Ireland was also acquired and their members helped in collecting or facilitating the collection of anthropometric data. Bishops and parish priests around the country were useful to the survey and ‘helped round up subjects’ for examination.95

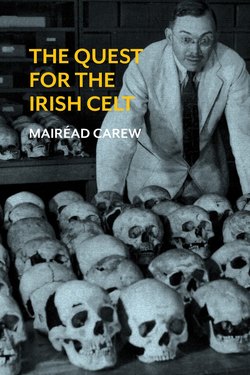

Measuring Celtic Skulls

To ascertain the race to which skulls recovered during archaeological excavations belonged, the Harvard Mission anthropologists employed the discredited nineteenth-century technique of mustard seed measurement. This technique, used to assess cranial capacity, was designed by a physician from Philadelphia, Samuel George Morton (who died in 1851), to find out the average size of human brains. Morton attempted to rank races according to the sizes of their brains. Stephen Jay Gould describes Morton’s technique and his abandonment of it in his book The Mismeasure of Man:

He [Morton] filled the cranial cavity with sifted white mustard seed, poured the seed back into a graduated cylinder and read the skulls’ volume in cubic inches. Later on, he became dissatisfied with mustard seed because he could not obtain consistent results. The seeds did not pack well, for they were too light and still varied too much in size, despite sieving. Re-measurements of single skulls might differ by more than 5 per cent, or 4 cubic inches. Consequently, he switched to one-eighth-inch-diameter lead shot ‘of the size called BB’ and achieved consistent results that never varied by more than a single cubic inch for the same skull.96

The physical anthropological examinations conducted by the Harvard team on skeletons from archaeological sites showed whether the skeletons had large brow ridges, pronounced prognathism or very long arms. Simian-type stereotyping of the Irish Celt, with negroid features, had been popular in American and British newspapers published in the nineteenth century.97 Scientific results obtained by the Harvard academics rivalled these imaginative and discriminatory depictions.

Hooton made helpful suggestions with regard to the reconstruction of the skeletons at the Bronze Age cemetery-cairn at Knockast in County Westmeath, excavated by the Harvard archaeologists, and collaborated with them in the preparation of the site report. Aleš Hrdlička also assisted in the examination of the bones.98 Hrdlička, a physical anthropologist, served on the anthropometric sub-committee of the American Eugenics Society (AES) with Hooton. They were both also on the Committee of the Negro with the leading American eugenicist Charles Davenport. This committee was established in 1926 by the American Association of Physical Anthropology and the National Research Council. Classifications of skulls at Knockast were deemed by the Harvard team to be significant as a large skull contained a brain which ‘from point of size is well above the average for modern Europeans’.99 The skull was described as dolichocephalic and orthognathous and the cranial capacity was established using mustard seed measurement.100 The archaeologists interpreted some skeletons at Knockast to be of a type which ‘one would normally expect on the basis of the present data with respect to Bronze Age man in Ireland’ a type which had been identified by Professor Shea of University College Galway. Professor Shea compared this type with that of the ‘short-cist people of Scotland’.101 The Harvard archaeologists believed that they could identify different races of people in the archaeological record based on physical anthropology, which they associated with differentiated cultural activities. For example, the ‘small cremating people’ identified at Knockast were deemed to represent a different physical type to those contained in the inhumation burials at the site.102 It was extrapolated from this that they represented an intrusive element at Knockast. The cairn was considered to have affinities with similar Late Bronze Age types in Britain. The conclusion was made that ‘the Late Bronze Age in Ireland must be considered intrusive, and Knockast the result of these new elements mingling with indigenous Bronze Age culture’.103

The idea that the cremating people were a different race, based largely on their different funerary practices, was contradicted by other evidence from Knockast where cremation and inhumation were for a time at least, contemporary rites. Bones from a cremated burial of a young woman were mixed with the skeleton of a child and some cremated remains were found under the child’s skull.104 These difficulties associated with correlating racial types with particular cultural assemblages or practices were acknowledged by the excavators.105 But, despite the limitations, much interesting information from an archaeological viewpoint was gleaned from physical anthropology about the lifestyle and health of the inhabitants of the site. For example, one male individual at Knockast had been badly crippled by arthritis and had recovered from a bad ear infection, leading Hooton to muse that ‘his recuperative powers must have been extraordinary’. There was also evidence for right-handedness and squatting.106 Sir Arthur Keith wrote about the skeleton found in the flexed position in the cairn at Knockast that it ‘may have Round Barrow (or beaker) blood in him’.107 The concept of equating a particular race with a specific artefact, pottery type, or monument type was popular in 1930s archaeological discourse.

Most of the human remains found in the Harvard excavations were sent to America for examination by physical anthropologists. A huge survey of skeletal remains was undertaken by the Harvard Mission at Gallen Priory, County Offaly in 1934 and 1935. T.D. Kendrick108 from the British Museum directed the excavation. He was assisted by Michael V. Duignan109 of the National Museum and the site was excavated under the Unemployment Schemes. Kendrick had invited the Harvard anthropologists to examine the site as ‘such quantities came to light that he felt the anthropological opportunities should not be wasted’.110 Gallen Priory was included in Harold G. Leask’s report on the more important archaeological results obtained from the Unemployment Schemes in 1935.111 Hooton along with William White Howells112 undertook the examination of the skeletons. They were both members of the Anthropometry sub-committee of the AES. Howells was Research Associate in Physical Anthropology at the American Museum of Natural History, New York (and later became a director of the AES in 1954). He pioneered cranial measurements in world population studies. In his study of the skeletons at Gallen Priory he observed that ‘the series has been described by the ordinary methods of craniometry’.113 Craniometry was a technique employed by Harvard anthropologists on the Irish sites and was ‘the leading numerical science of biological determinism during the nineteenth century’.114 Howells accepted the limitations of this technique, acknowledging that the examination of morphological features were sometimes subjective, such as the measurement of the ‘degree of prognathism’. Two observers may differ in their personal perceptions of a classification, and, in his opinion, it was ‘difficult for a single observer to maintain a constant standard when he has no ‘standard’ outside of his own mind to which to refer’.115 Hooton remarked that ‘if they are somewhat unsatisfactory they are at least better than nothing at all’. He advocated that the standard should be ‘the typical development in the adult male cranium of the north of Europe’.116 Howells, despite using the technique was not convinced of its accuracy and wrote prophetically that ‘these conclusions with regard to the prehistoric people have been arrived at on the basis of craniology alone. Therefore, even though archaeology may in the future show them to be wrong, the cranial evidence will have been given its full weight’.117

The study of the Gallen skeletons was published in the Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy in 1941.118 Hooton referred to the work as an ‘admirable study’. Howells’s work was used as a basis for comparison of the modern Irish population as it was the largest skeletal series of the Irish that had ever been available for examination.119 Adolf Mahr was satisfied that the Gallen skeletons ‘will provide a welcome body of information, from which to draw conclusions also as to the racial characteristics of the population in the period immediately preceding the Early Christian centuries’.120 Howells observes in his study of the skeletal remains that three quarters of the Gallen skulls can be described as orthognathous, ‘as is to be expected among Europeans’.121

The comparative material used included Aleš Hrdlička’s work on the Irish in the USA, included in a general discussion on the white race, published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology in 1932.122 Howells also based his work on that of G.M. Morant, who examined crania in England and Scotland and compiled series of cranial types for Neolithic, Bronze and Iron Age peoples.123 Howells described the Neolithic type as ‘homogeneous, purely dolichocephalic, narrow-nosed and short-faced’. However, this changes in the Early Bronze Age ‘due to the incursion of a well-defined brachycephalic type’.124 Howells suggested that ‘the true time-sequence be violated’ and that the larger collections of Iron Age crania should be compared with those of later times.125 These larger collections included the Anglo-Saxons and seventeenth-century Londoners. He observed that ‘The evidence which the later groups afford has led Hooke and Morant, and Keith also, to conclude that the Iron Age folk, whatever their own origins, form the basis of the modern population without influences from the Anglo-Saxons’.126 Howells concluded that the Gallen type ‘can only be descended directly from the Irish Iron Age’.127 He ascertained that the skeletons represented an ‘homogeneous blend’ of dolicocephalic Neolithic and brachycephalic Bronze Age stock.128 This anthropological blending allowed for a solid continuity without compromising the purity of the stock.

In 1935, C.P. Martin, Chief Demonstrator of Anatomy at Trinity College Dublin, wrote that ‘The Iron age passes almost imperceptibly into the early Christian era so far as archaeology is concerned’.129 C.P. Martin’s work was dismissed by Howells because Martin had ‘published measurements on all of the known Irish crania of early and recent times, but without reaching any significant conclusions’.130 Martin himself conceded in his book Prehistoric Man in Ireland that his series of skulls was ‘small as a basis for compiling reliable statistics’.131 Howells saw similarities between the Iron Age, Crannóg and Early Christian skulls, arguing that ‘the Iron Age and crannóg skulls approach the Gallen type; the Iron Age skulls are very much like the British Iron Age series, or between this and the Gallen type; while the Crannóg skulls are near to the Gallen series, and the Early Christians [ …] are practically identical with it’.132 While Howells acknowledged that ‘archaeology makes it clear that in England the advent of iron was accompanied by invaders’ he also accepts Adolf Mahr’s theory that ‘in point of numbers the Iron Age immigration to Ireland was small and unimportant’.133 Howells corroborated Mahr’s stance, stating that the Gallen skeletons ‘gives a cranial type which calls for no Iron Age invasion’.134 Hooton published a paper entitled ‘Stature, head form and pigmentation of adult male Irish’ in 1940.135 In MacNeill’s view ‘the anthropometric statistics in this paper are deeply interesting and must have great significance. They should form a basis and give a stimulus for a more complete study’. However, MacNeill dismissed remarks made in Hooton’s paper which connected the Irish language with physical racial features.136

The Racial Celts: Modernist Fantasy or Scientific Fact?

The Australian prehistorian, V. Gordon Childe, described in Sally Green’s biography, as ‘the most eminent and influential scholar of European prehistory in the twentieth century’,137 influenced a generation of British and Irish archaeologists, including Macalister.

Childe was influenced by the racial ideology of the times, reflecting the pervasiveness of eugenic ideas and the nineteenth-century ranking of races which was still in vogue in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1926, he published a book The Aryans, expressing the view that the Aryans were ‘the linguistic ancestors’ of the Celts.138 He commented that the Aryans bequeathed to their linguistic heirs ‘if not skull-types and bodily characteristics, at least something of this more subtle and more precious spiritual identity’.139 This reference to the Celtic language reflected Childe’s interest in philology and Indo-European origins.140 He asserted that ‘it was the linguistic heirs of this people who played the leading part in Europe from the dawn of history and in Western Asia during the last millennium before our era’.141 While he was later to dismiss this tome and exclude it from his ‘Retrospect’,142 published towards the end of his life, it is worth noting that he too, came under the influence of prevailing political ideologies. Childe described the physical attributes of the Aryans as follows:

The physical qualities of that stock did enable them by the bare fact of superior strength to conquer even more advanced peoples and so to impose their language on areas from which their bodily type has almost completely vanished. This is the truth underlying the panegyrics of the Germanists: the Nordics’ superiority in physique fitted them to be the vehicles of a superior language.143

This physical description could equally be applied to the story of the Celtic invasion of Ireland. In 1935, Macalister described the Iron Age ‘invasion’ in terms of ‘the flashing iron blades of the tall, fair-haired newcomers, who landed one fateful day in or about the fourth century BC’.144 This white supremacist, Eurocentric worldview allowed for the Irish to be classified as European stock, with the implication of a Nordic dolichocephalic heritage. Andrew P. Fitzpatrick made the point that studies of the Celts creates ‘an essentially modernist fantasy.’145