Читать книгу The Quest for the Irish Celt - Mairéad Carew - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

THE HARVARD ARCHAEOLOGICAL MISSION IN THE IRISH CULTURAL REPUBLIC

The outstanding feature of Ireland’s cultural development and of her position in the civilised world may be stated thus: she is not the cradle of the Celtic stock, but she was its foremost stronghold at the time of the decline of the Celts elsewhere; she is the most wonderful artistic province of the Celtic spirit, its centre of missionary enterprise, its last refuge; pre-eminently the Celtic country. Ireland is now the only self-governing State with an uninterrupted Celtic tradition, and has the duty of becoming the country for Celtic Studies.1

– Adolf Mahr, 1927

Archaeology and Politics in the Irish Free State

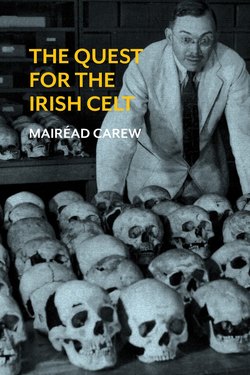

The Harvard Mission to Ireland2 was a large-scale anthropological study of the Celtic race in Ireland, funded mainly through grants and donations administered by the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University.3 The Irish Free State made funding available for the archaeological strand from 1934 by defraying the costs of labour through Unemployment Schemes.4 While the project contained three strands: social anthropology, physical anthropology and archaeology, the focus of this chapter and the book as a whole is the archaeological strand and the corroborating evidence from physical anthropology.5 In America in the 1930s the academic discipline of anthropology was sub-divided into four topics for study: archaeology, physical anthropology, ethnology and linguistics. The Harvard School specialised in archaeology and physical anthropology.6 The aim of the Harvard Mission was to study the origin and development of the races and cultures of Ireland.7 Large-scale scientific excavations were carried out between the years 1932 and 1936 and the physical examinations of thousands of Irish people became part of the nation-building project of the Irish Free State, focussing on cultural revitalisation programmes (between 1922 and 1948) under the auspices of nationalist governments.8 The Harvard Mission archaeologists included Northern Ireland in their survey of the Irish Free State. This was because, as the Director of the archaeological strand, Hugh O’Neill Hencken asserted, ‘the territory was an integral part of Ireland’ prior to the seventeenth century.9 Excavations were carried out on both sides of the border. Academic journals such as the Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland and Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy welcomed articles on Irish archaeology from all over the island. Neither organisation changed this policy after the establishment of the border. In contrast, The Ulster Journal of Archaeology had a regionalist policy and papers were primarily focussed on Ulster archaeological research.10 The Harvard Mission to Ireland included three years of fieldwork and two years of analysis and preparation of reports.

The Harvard Mission became part of the essentialist drive of the de Valera government to establish a cultural republic in the 1930s. The institutionalisation and professionalisation of native cultural endeavour began after 1922. It included archaeological initiatives as antiquities were considered crucial in the process of imagining the nation.11 The ‘imagined community’ envisaged by Benedict Anderson12 was given visual and tactile expression through material culture. Monuments and artefacts applied a sense of concreteness, permanence and longevity to the abstract concept of the nation. The Harvard Mission was also an expression of diaspora nationalism which saw an attempt to improve the social and economic circumstances of the Irish in America through Celtic cultural endeavour.13 Irish-Americans contributed financially to the Harvard research: this was facilitated by Judge Daniel O’Connell and his brother, the ex-Congressman Joseph O’Connell, who organised the Friends of the Harvard Anthropological Survey of Ireland.14

Hugh O’Neill Hencken, the leader of the archaeological strand, was of Irish and German extraction. His grandfather, also called Hugh O’Neill, left Newtownards, County Down in 1854 to travel to Belfast, where he sailed for New York. He became a well-known dry-goods merchant in New York and served as Patron of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Natural History Museum.15 Hencken was educated at Princeton University in America and Cambridge University in England. By 1931 he was Assistant Curator of European Archaeology at the Peabody Museum in Harvard. This success reflected the rising fortunes in social and economic terms of the Irish in America in the early decades of the twentieth century. In 1934, the early Irish historian, Eoin MacNeill, expressed the view that ‘a right appreciation of Ireland’s place in history disseminated in America must contribute to the cultural and spiritual upbuilding of America’.16 Indeed, it was following MacNeill’s successful tour of universities in the United States in 1930 that the Harvard Mission began its work in Ireland in 1932.17

Irish Archaeology: The Playground of the Politician?

Irish-Ireland ideology and anthropological modernism underpinned the cultural regeneration of the nation-state between 1922 and 1948.18 De Valera sent the Saorstát Éireann Official Handbook of the Irish Free State, edited by Bulmer Hobson, and commissioned by the Cosgrave government, to the Chicago World Fair (1933–4) to accompany an Irish Free State cultural exhibition. It was intended to provide ‘a survey of the progress made’ by ‘the end of the first decade of national freedom’ and included essays on Irish history, archaeology, folklore, literature, Irish language, art, industries, geology and tourism.19 Despite this progress, R.A.S. Macalister, professor of Celtic Archaeology at UCD from 1909 to 1943, continued to worry about the intertwining of archaeology and politics, and expressed the view that ‘the archaeology of Ireland is worthy of a better fate than to become the playground of the politician’.20 However, in Ireland between the years 1922 and 1948 it was virtually impossible to disentangle archaeology from political influence. This was because archaeology as a discipline does not function independently of the societies in which it is practised and has a value for the present.21 In order to understand the rise of archaeology as a discipline it must be examined in a socio-cultural and political context.22 This is important in the interpretation of the work of the Harvard Mission to Ireland, which began with a trip by American archaeologists to Ireland in 1931 in order to determine which archaeological sites would be selected for excavation as part of a five-year project.

The Harvard Mission excavations took place during a period, described by the Cambridge archaeologist, Grahame Clark, of ‘intense archaeological activity’ following the establishment of the Irish Free State.23 However, while this comment is correct it is made without elaboration. Other important initiatives which could be included were the development of a native school of Irish scientific archaeology and the setting up of the Unemployment Schemes for archaeological research in 1934. These initiatives, driven by nationalist ideals, placed Ireland at the forefront of European archaeology in the 1930s. The Harvard Mission excavations were central to this development. After independence, Clark noted that the state continued to strive for a separate national identity through the medium of archaeology and described the process as the ‘nationalisation of archaeological activities’.24 He points out that this intense activity did not fully survive the attainment of political objectives. Waddell agrees that ‘the bright promise of the 1930s is hard to discern in the following two decades’.25 However, the important fact remains that Irish archaeology was a necessary ingredient to the attainment of political objectives as cultural activity often presages or acts as a catalyst for political activity. It was hugely important to the nation-building project during this period as it was then scientifically possible, through the practice and methods of archaeology, to recover proof of the antiquity of the Irish Celtic race. This cultural authority of science consolidated and validated political identity. The discipline of archaeology was rooted in the landscape and, therefore, the territory defined as the homeland, the definition of which was essential to the nationalist agenda. Attempts were also made in the 1930s to establish an American School of Celtic Studies at the National Museum of Ireland.26 While this did not materialise, de Valera included a School of Celtic Studies in the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies in 1940, an idea initially mooted by Eoin MacNeill.27

The Harvard Mission and Irish-Ireland Ideology

In the Irish Free State the native expression of cultural activity was the consolidation of the doctrine of Douglas Hyde when he pleaded for an Irish nation ‘upon Irish lines’ in his famous speech ‘The Necessity for De-Anglicising Ireland’, delivered to the National Literary Society in Dublin on 25 November 1892.28 Hyde (later to become the first President of the Irish Free State in 1938) postulated that it was ‘our Gaelic past’ which prevented the Irish from becoming ‘citizens of the Empire’.29 He exhorted all Irishmen to speak the Irish language, revive Irish customs, buy Irish goods, and play Irish music and Irish sports. Hyde believed that ‘our antiquities can best throw light upon the pre-Romanised inhabitants of half Europe’.30 This was important to the creation of an Irish national identity because it was believed that Ireland, unlike many other European nations, had developed independently and was, therefore, free of Roman influence. This belief, which the Harvard archaeologists shared, influenced their interpretations of the crannóg excavations.31 Archaeology was necessary to demonstrate the material culture of a nation which Hyde described as ‘the descendant of the Ireland of the seventh century, then the school of Europe and the torch of learning’.32

With independence came the prioritisation of native cultural expression. There was also an impetus to institutionalise the cultural endeavours which had previously been the preserve of the educated middle and, particularly, the upper classes, such as the collection of antiquities and folktales. In his discussion of the Gaelic League Tom Garvin argues that politicians of independent Ireland ‘had imbibed versions of its ideology of cultural revitalisation’.33 Archaeology became the material expression of this ‘cultural revitalisation’ in the 1920s and 1930s. These ideas were also reflected in D.P. Moran’s book The Philosophy of Irish Ireland, published in 1905. Eoin MacNeill expressed a similar view in the Irish Statesman on 17 October 1925 and commented that ‘if Irish nationality were not to mean a distinctive Irish civilisation, I would attach no very great value to Irish national independence’.34

Archaeology, Modernism and the Celtic Revival

In his book Modernism and the Celtic Revival, Gregory Castle refers to ‘the increasing cultural pessimism of the late nineteenth century and the claim that not only the population of cities but the world itself, that is the West, was degenerating’.35 This resulted in an idealisation of rural life which is evident in the writings of W.B. Yeats and others from the Cultural Revival period. This was a rejection of urban culture with its associated side effects of industrialisation, including poverty and social problems. Hyde’s version of the nation, emphasising the soil, the Irish race and the Irish language was the vision of deAnglicisation which de Valera promoted. Eugen Weber discusses similar ideas in French culture in his book Peasants into Frenchmen. He explores how land, the soil, physical activity and health were essential to ruralist conservatism in France. This was interpreted as an expression of the nation’s soul with its hostility to modernity, urban life and cultural diversity.36 de Valera’s much derided 1943 speech, broadcast on the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the Gaelic League, expressing ideas of rural romanticism, youthful health and racial purity, can also be seen in this light.37

In his book Castle explores what he terms, ‘an underlying affinity between anthropology and modernism’.38 He explains that anthropological observations and the study of the past was an essential part of the modernist agenda. The Harvard Mission to Ireland could be placed in this context whereby modern physical and social problems could be solved through the medium of science in the 1930s. Castle notes that ‘the desire to revive an authentic, indigenous Irish folk culture is the effect of an ethnographic imagination that emerges in the interplay of native cultural aspirations and an array of practices associated with the disciplines of anthropology, ethnography, archaeology, folklore, comparative mythology, and travel writing’.39 In the 1890s anthropology, archaeology and ethnography were emerging scientific disciplines. The West of Ireland became important to the Celtic Revivalist and anthropologist alike. For example, J.M. Synge, author of The Aran Islands, was educated in continental Celticism and studied under the French Celtic scholar, Henri D’Arbois de Jubainville. Synge attended lectures on Celtic culture and mythology, philology and cultural anthropology at the Sorbonne in Paris.40 Revivalists and anthropologists attempted to reclaim traditions, histories, and cultures from imperialism and ‘to reclaim, rename, and reinhabit the land’.41 This pivotal role of anthropology in the Celtic Revival resulted in ‘autoethnography’, as native intellectuals attempted to represent themselves to the coloniser using the language and methodology of the colonial discipline of anthropology.42

In the Irish Free State’s programme of native cultural revitalisation, anthropology, archaeology, Irish language, folklore and native traditions became important in themselves rather than as motifs illustrating Irish literature in the English language. The Harvard Mission as part of this revitalisation programme can be described as a modernist project in the sense that it was an anthropological survey to study scientifically a society in transition between tradition and modernity. John Brannigan, in his book Race in Modern Irish Literature and Culture, explains that ‘the Harvard study should be contextualised as an important moment in the evolution of the modernist state, in which social and physical sciences were understood to be strategic instruments vital to the bio-political ambitions of the state’.43 The scientific establishment of the credentials of the Celtic race by international archaeological and anthropological expertise was essential to these political aspirations.

The combined native and internationalist dimensions to cultural production fitted de Valera’s anthropological cultural vision, emphasising cultural heritage as a pathway to the future for an independent republic. Nicholas Allen, in his paper ‘States of Mind: Science, Culture and the Irish Intellectual Revival, 1900–1930’, makes the point that ‘Immediately after the Anglo-Irish and Civil Wars, we find the discourse of science applied widely in support of cultural, political, and economic development in the new state’.44 While Allen doesn’t refer to archaeology in his article, his ideas can also be applied to the Harvard Mission’s work as the Harvard academics applied scientific techniques of American archaeology to their work in Ireland. American archaeology had become increasingly scientised in the early decades of the twentieth century.45

Irish: The Language of the Celts

Albert Earnest Hooton46, the American physical anthropologist and manager of the Harvard Mission, wrote about the importance of the Irish Free State, citing that one of the reasons for choosing it for a Harvard survey was because of ‘the Celtic tongue, an archaic Aryan language once spoken over a large part of Europe’.47 Hugh O’Neill Hencken, like his contemporaries, took an interest in Celtic, an Indo-European language. He was later to publish a book entitled Indo-European Languages and Archaeology as a volume of the American Anthropologist in 1955.48 According to G.R. Isaac in his paper ‘The Origins of the Celtic Languages: Language Spread from East to West,’ it is still impossible to discuss the origin of the Celts without reference to the Celtic language. He argues that ‘without language, there are no Celts, ancient or modern, but only populations bearing certain genetic markers or carriers of certain Bronze Age and Iron Age material cultures. The origin of the Celts therefore is the prehistory and protohistory of the Celtic languages’.49 The Irish language, therefore, as well as the material culture of the Celts, were deemed important areas of study in Irish universities in the nineteenth century and this continued after independence in 1922.

In 1854, Eugene O’Curry had been appointed to the first Chair of Celtic Archaeology at the Catholic University. R.A.S. Macalister became the first Professor of Celtic Archaeology at University College Dublin in 1909. Douglas Hyde, president of the Gaelic League from its foundation in 1893 to his resignation in 1915 for political reasons, campaigned for and succeeded in making Irish a compulsory subject for matriculation to the newly established National University of Ireland in 1908.50 The state took over the Gaelic League’s educational function by including Irish as a compulsory subject in the educational system and by setting up the special Government Publications Office, An Gúm, in 1926.51 The Irish language was established as the national language in Cosgrave’s 1922 constitution and was also given this status in de Valera’s 1937 constitution. By 1934, in his keynote speech at the International Celtic Congress held in Dublin from 9–12 July, Douglas Hyde was still advocating for the preservation and propagation of the Irish language. At this stage, Éamon de Valera, who was in the audience together with Maud Gonne, Agnes O’Farrelly and delegates from Brittany, Scotland, Wales and the Isle of Man, had pledged his backing for a permanent research institute where all the Celtic languages might be studied’.52

Patrick Pearse, who had served as the editor of the League’s journal, An Claidheamh Soluis (1903-1909), aimed to create ‘a modernist literature in Irish’.53 He argued that ‘Irish literature if it is to live and grow, must get into contact on the one hand with its own past and on the other with the mind of contemporary Europe’.54 By the 1930s literary works of ‘an indigenous tradition of amateur self-ethnography’ appeared.55 These included books such as Maurice O’Sullivan’s Twenty years A-Growing, The Autobiography of Peig Sayers of the Great Blasket Island, Tomás Ó Crohan’s The Islandman, and Pat Mullen’s Man of Aran. Irish-speaking islanders were regarded in this period as pre-industrial and pre-modern. Ideas about degeneration in cultural and racial terms, a common discourse in the 1930s, fed into the need for regeneration through cultural, economic, political and moral projects in the Irish Free State. One of the most influential cultural critics in the interwar period in Ireland, the writer Seán O’Faoláin, criticised the Irish language revival, referring to ‘the poverty and degenerate nature’ of Gaeltacht culture’.56 This rhetoric is similar to that of the nineteenth-century colonialist writers on Ireland. The use of the word degenerate is disingenuous as the impetus of the Irish language revival and native cultural regeneration in general was an attempt to address the perceived degenerate nature of culture, race and society at that time.57 Comhdháil Náisiúnta na Gaeilge (a new umbrella co-ordinating body for Irish-language organisations) was established in 1943.

The 1930s can be seen as the apogée of a native cultural revitalisation programme which began with Hyde’s speech and served as the cultural blueprint for the independent state. The Irish Free State, under Cosgrave in the 1920s and de Valera in the 1930s, favoured cultural activity which fitted into this ideological framework. Unfortunately, Irish-Ireland ideology got a bad name because of the vitriolic outpourings of journalists such as D.P. Moran.58 The impetus for regeneration in the Irish Free State was part of a wider European project where nation-states across Europe defined their nationhood in terms of race, culture, language and purity. These modernist regeneration projects included the enactment of laws which institutionalised concepts of national culture, and embedded it in the political agenda of the state. The nationalist governments of Cosgrave and de Valera shared a similar Irish-Ireland cultural ideology. Attempts to establish the racial credentials of the Irish as Celtic dovetailed neatly with the American agenda of the Harvard anthropologists and archaeologists. They concentrated on rural dwellers for their anthropometric survey as they believed that ‘the country people were perhaps more truly representative of Irish racial types and less likely to be mixed with recent foreign blood than would be the city dwellers’.59

From Hyde to Lithberg

As part of the deAnglicisation project Douglas Hyde had written about the importance to the Irish nation of the collections of a national museum and the necessity of gathering antiquities and ‘enshrining’ each one of them in ‘the temple that shall be raised to the godhead of Irish nationhood’.60 When Hyde penned these words, no doubt, he was not referring to all vestiges of the past but to selected items from what he perceived to be a Celtic, Irish and Christian past. The idea that ‘relics’ of the Gaelic past should be displayed or contained in a sacred building such as a temple expresses the veneration of an idyllic past, or Golden Age, which was a central tenet of the doctrine of Irish nationalism. The raising of this building to ‘the godhead of Irish nationhood’ further expands on the idea that the past and how its interpretation was controlled through museum display became important in terms of imagining and defining the nation.61 These museum exhibits were a means of transmitting ideas about national territory, history and homeland, and reflect the nation in microcosm. The selection process itself was part of this nationalist endeavour. The Dublin Museum of Science and Art was opened in 1890 and was formally renamed the ‘National Museum of Science and Art, Dublin’ by its Director, George Noble Count Plunkett, in 1908. Count Plunkett, a cultural nationalist and Home Ruler, was father of the executed 1916 leader Joseph Mary Plunkett. The new title, according to Plunkett, was ‘more appropriate for the institution having regard to its representative position in the capital as the Museum of Ireland and the treasury of Celtic antiquities’.62

A State Framework for Irish Archaeology

Archaeology, as a useful political tool, underpinned visually the identity of the state as Celtic and Catholic. The process whereby ‘culture became a surrogate for politics’ applied to the discipline.63 It is described by Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh as a ‘cultural vision of decolonisation’.64 This decolonisation process, involving the reclamation, culturally and politically, of archaeological monuments and artefacts, had already begun in the nineteenth century. This is exemplified in the media furore over the British Israelite excavations for the Ark of the Covenant at the Hill of Tara in 1899–1902. Cultural nationalists, including Arthur Griffith, Douglas Hyde, W.B. Yeats, Maud Gonne and George Moore were involved in the protests to get the digging stopped as they regarded it as a ‘desecration’ of Tara, the capital of an ancient and independent Ireland. At the time, British Israelites regarded Tara as a royal site in the British Empire. They wished to recover the Ark and present it first to Queen Victoria and later to her son Edward VII.65

Another controversy of note at the end of the nineteenth century was the contested ownership of the Broighter hoard, discovered in 1896 in Co. Derry. The hoard, deposited some time after 100 BC consisted of gold objects, including two bar torcs, two necklaces, a bowl, a buffer torc and a beautiful model boat with oars and a mast. The objects were sold to a Derry jeweller, who sold them to Robert Day, an antiquarian, who sold them to the British Museum. The prominent Unionist, Edward Carson, represented the Royal Irish Academy (RIA) at a subsequent court case. The hoard was deemed to be ‘treasure trove’ and handed over to King Edward VII, who gave it to the RIA and the hoard later became part of the celebrated gold collection of the National Museum of Ireland.66

After independence the dominant cultural vision of nationalist elites was embedded into the discipline, reflected in the policies and practices of Irish archaeology. In 1927 the creation of a state framework for Irish archaeology was achieved by the provision of a new cultural policy document for the National Museum of Ireland: the 1927 Lithberg Report, prioritising Celtic and Christian artefacts; and the framing of the National Monuments Act, 1930, which defined a ‘National Monument’ for the first time. These important initiatives not only provided the framework within which Irish archaeology was practised under state control but also reflected the influence of Gaelic League ideology. Professor Nils Lithberg of the Northern Museum of Stockholm was commissioned to write a report on the purpose of the National Museum by the Irish Government. He was chosen for the task because the Northern Museum of Stockholm was ‘one of the most notable national museums in Europe’.67 Lithberg had been appointed as the first holder of the position of Professor of Nordic and Comparative Folklife Research there in 1918. The Northern Museum of Stockholm was described by Barbro Klein as a ‘culture-historical museum’.68 Culture-historical archaeology became popular towards the end of the nineteenth century. It was influenced by nationalist political agendas and used to prove a direct cultural or ethnic link from prehistoric peoples to modern nation-states. Growing nationalism and racism, according to Bruce Trigger ‘made ethnicity appear to be the most important factor shaping human history’.69 The Lithberg Report was the blueprint for a culture-historical museum in Ireland. It was very important in the context of the politics of museum display and was a key document in the nationalisation policy of the government for Irish archaeology.70 It was recommended that the collections should be ‘firmly based on Ireland’s native culture’ and that the gold ornaments from the Early Bronze Age, the artefacts from the pre-Roman Iron Age and the Early Christian Period should be kept separate so that ‘the collections will receive the glamour of ancient greatness to which they are entitled’.71 In the process, as Elizabeth Crooke put it, ‘The Museum and the Irish nation was reinventing itself’.72

The Lithberg Report was also important in the context of European identity. The American involvement in Irish Free State archaeology gave it a global resonance and satisfied an American desire in the 1930s for roots in old Europe. Thousands of artefacts recovered by the Harvard Mission archaeologists during their five-year project in Ireland were deposited in the National Museum. How the past was packaged for the viewer and how selected artefacts were displayed in the museum illustrated the official narrative of the nation’s history. This reflects Ernest Gellner’s view of the political principle of nationalism that ‘the political and the national unit should be congruent’.73 Culture, as represented by archaeology in the Irish Free State and its strategic display in a national institution was a politically aspirational endeavour. The emphasis on archaeology in the National Museum was heavily criticised by Sir Thomas Bodkin. He blamed this on the two former directors of the National Museum, the prehistorians Walther Bremer and Adolf Mahr, writing that ‘neither of them professed interest in the Fine Arts, and their well-nigh exclusive preoccupation with archaeology worked to the great disadvantage of the Museum’.74

The introduction of new legislation for the protection of archaeological heritage was also politically aspirational. In an address delivered to the Royal Irish Academy in 1927, R.A.S. Macalister, President of the Royal Society of Antiquaries, stated that ‘Ireland must remember that she holds in trust for Europe a large number of ancient monuments of unique importance: and the sooner legislation is obtained to facilitate the nationalisation of these monuments, the better it will be for the national credit of the Free State’.75

In the legislation enacted finally in 1930, a ‘National Monument’ was defined as ‘a monument or the remains of a monument the preservation of which is a matter of national importance by reason of the historical, architectural, traditional, artistic, or archaeological interest attaching thereto’.76 The word ‘national’ was a political rather than a cultural designation.77 The definition of ‘national monument’ caused difficulty because if politicians decided that the preservation of particular monuments was not a matter of ‘national’ importance, in theory at least, they didn’t have to be protected. The Dáil debates surrounding the National Monuments Bill give an insight into the political opinions involved in the interpretation of key concepts contained in the legislation. The embeddedness of a desired identity, reflected in the type of monument deemed to need protection, served the cultural and political needs of the state at that time.78

The debate about the validity of protecting Big Houses, seen as a vestige of Protestant identity, also surfaced. According to Terence Dooley, this was because the landed class ‘had come to symbolise colonial rule and their houses were symbols of an old order.’79 Apart from the symbolic and political difficulties inherent in their preservation there was also the prohibitive cost to consider’.80 For example, Coole Park, the residence of Lady Gregory, was sold to the Department of Lands in 1927 and demolished in 1941. There was some disquiet about its demolition expressed in newspaper coverage of the time because of Lady Gregory’s association with the Irish Literary Revival, W.B. Yeats and the founding of the Abbey Theatre. At the time, Lady Gregory and Coole Park were not seen as culturally valuable from an Irish-Ireland perspective.81 The Chairman of the Board of Works expressed the view that ‘no one is going to deny Lady Gregory’s claim to a place of honour in Anglo-Irish literature but it is straining it somewhat to suggest that her home should be preserved as a National Monument on that account’.82 If money was spent on preserving such buildings, it was argued, the excessive cost might affect the preservation of ‘real national monuments’.83 Examples of ‘real national monuments’ included Newgrange, round towers, churches at Glendalough and the Rock of Cashel. If the meaning of the monument was contested, its ‘national’ essence was not secure, resulting in the structure not being covered under the definition in the legislation. Similar legislation to protect national monuments was enacted in France, Germany, Italy, Greece, Austria, Belgium, Holland, Switzerland, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Spain, Portugal, Russia, Turkey, Palestine and Great Britain.84

The law against unlicensed excavations and the unauthorised export of antiquities was very important as prior to this, archaeological expeditions, carried out by America and Britain to Egypt and other countries, had resulted in the looting of archaeological material and the export of it to the country of origin of the archaeologists. This was something which worried Macalister with regard to the Harvard Mission. A concern among archaeologists had been reported in an article published in the Irish Press in 1932 ‘that a wealth of Irish antiquities may find their way across the Atlantic instead of being preserved at home’.85 Hugh O’Neill Hencken and Hallam L. Movius Jr. made a statement in 1934 that ‘It is the policy of Harvard University that the objects found during excavations should become the property of the National Museum of Ireland’.86 Unlike the strict legislation in the Irish Free State, the Ancient Monuments Acts (Northern Ireland) of 1926 and 1937 did not make illegal the export of archaeological material which resulted in the shipment of material to America.87

While Douglas Hyde’s ideas about embracing all Irish cultural activity were adopted by the government of the Irish Free State, this did not include archaeological manifestations of Protestant identity. Síghle Bhreathnach-Lynch expresses this idea succinctly:

In keeping with other nations emerging from colonial rule, not surprisingly, the new Irish state was anxious to establish as soon as possible a distinctive national character, one that was as different as possible from that of its erstwhile ruler. Great Britain was perceived as urban, English-speaking and Protestant. Ireland would go to endless lengths to prove itself to be the opposite: rural, Irish-speaking and Catholic. A significant aspect of this construct of identity was the belief that Ireland’s national identity was rooted in a Golden Age, that is the ancient Celtic past.88

Culture-historical ideas were embedded in the Lithberg Report and the National Monuments Act as the cultural value of artefacts and archaeological monuments were established within this framework. The parameters of the selection process of sites excavated by the Harvard Mission and under the Unemployment Schemes and the subsequent interpretative paradigm used was also defined by this. It enabled the state to control the creation of archaeological knowledge and to make political claims to disputed territory though the medium of archaeological discourse (see Chapter 6).

Archaeology and Folklife

The Harvard Mission archaeologists included reports on local folklore in their scientific papers.89 Archaeology in this period was directly linked with the life of ordinary people. This was part of a democratisation of culture, a European phenomenon, and an expression of anthropological modernism. In the Lithberg Report, for example, it was recommended that ‘on these two principles, that is, the knowledge of Ireland’s earlier culture and of the present day life of the people, should in my opinion, an Irish National Museum be based’.90 To this end it recommended the creation of a folklife section in the National Museum. The Folklore of Ireland Society was created in 1926. The Irish Folklore Institute was formed in 1930 and received finance by way of a Cumann na nGael government grant and a Rockefeller Foundation grant of £500. Within five years the institute had built up a collection of over 100 manuscript volumes. This important work was continued by the de Valera government with the establishment of the Irish Folklore Commission in 1935 and in 1937–8 the innovative Schools Collection was carried out. Séamus Ó Duillearga, who was involved in the setting up of the Irish Folklore Commission, travelled extensively in Scandinavia and established strong academic and cultural ties there.91 Micheál Briody notes that the Irish Folkore Commission was the first such organisation devoted solely to the collection of folklore in any country and succeeded in ‘assembling one of the finest and most extensive collections of folk tradition in the world’. 92 In 1936, at the inaugural meeting of the Historical Society of UCD, Ó Duillearga, then director of the Folklore Commission, pointed out that scholars on the continent and in America were taking particular interest in its work. In a letter dated 2 November 1938 from the Department of External Affairs to Maurice Moynihan, Secretary, Department of the Taoiseach, it was noted that ‘Ó Duillearga was going to deliver a series of lectures on folklore in the American Universities in the Spring and that Ó Duillearga desired ‘to extend the operations of the Folklore Commission to the Six county area.93 Ó Duillearga’s UCD address in 1936 on the oral tradition was entitled ‘An Untapped Source of Irish History’. He described the work of the Folklore Commission as embracing ‘everything of a traditional character which could throw light on the social and cultural life of the Irish people of past times’.94 In his book, Briody observed that ‘The Irish Folklore Commission achieved international status by bypassing England and going to, what it considered, the fountainhead of folklore scholarship,’95 the northern countries of Europe. The establishment of a folklife collection at the National Museum became more important after political independence. In 1935 the Folklore Commission invited Ake Campbell and Albert Nilsson, two Swedish ethnologists, to come to Ireland on a ‘Folk-Life Mission’ to make a survey of Irish rural farmhouses.96

Adolf Mahr, a friend of Ó Duillearga’s, and board member of the Irish Folklore Commission, was also involved in the Quaternary Research Committee, set up in 1934, which brought the Danish mission to Ireland; their work on the bogs had important scientific implications for Irish archaeology.97

Archaeology and the Democratic Ideal

It was explained in the Lithberg Report that the object of a Historical Museum was not to collect objects of artistic and monetary value as these objects have ‘an intrinsic capacity of preserving themselves’ but to collect ‘more simple objects which have a small market value and for this reason are threatened with destruction’.98 The ideal of a National Museum should be ‘to give a consecutive representation of the native civilisation of the country from the time when the human mind first showed its creative power until the present day, and it should embrace all classes which have been or still are components of its society’.99 This sentiment reflects the democratic ideal of the independent nation-state. It also reflects the fact that archaeology was no longer the preserve of the monied and leisured classes but was a state-sponsored activity.

Malcolm Chapman has noted that the ‘Celts’ and the ‘folk’ often seem ‘virtually conterminous categories’ because ‘folklore’ like the idea of the Celts had become romanticised.100 This idea of the idyllic life of the peasantry was a throwback to the nineteenth-century cultural-nationalist idea of the pure, native, Gaelic-speaking, rural-dwelling Irishman. According to Joep Leerssen, a sense of Irish cultural identity came to be located in antiquity and peasantry in the nineteenth century.101 This trend of glorifying ‘past and peasant’ continued into the twentieth century and was given material expression in the nationalist museums of Europe in their folk-life collections. The recommendations for the folklife section contained in the Lithberg Report were based on the open-air museum at Skansen in Stockholm.102

One of the Harvard Mission anthropologists, Conrad M. Arensberg, commented in his book The Irish Countryman that: ‘The folklorist has discovered Ireland, and today the Free State Government subsidises the preservation of folklore as a monument to national greatness’.103 Folklore and superstition were also important in the preservation of archaeological monuments. Macalister lamented the fact that superstitions were ‘once potent in preserving the ancient monuments’. He worried that ‘unless something intervenes to stay the damage, the world will lose many of the lessons that Ireland, and Ireland alone, can teach’.104 But these superstitions lingered and local people were sometimes suspicious of the scientific work of the Harvard archaeologists, with their emphasis on physical anthropology. For example, Rev. L.P. Murray, editor of the County Louth Archaeological Journal was worried that the respect shown for burial grounds by ordinary people would be diminished by the work of the Harvard Misssion and would lead inevitably to the destruction of more monuments in the future. He criticised the methods used in excavating the Bronze Age burial site at Knockast, Co. Westmeath. He did not agree with disturbing the remains of the dead and he questioned the use of bone measurements to acquire useful archaeological data.105 He described their work at burial-sites as ‘ghoulish performances’ and posed the question: ‘If it is permissible, today, to rifle a Bronze Age cemetery, will it not also be permissible, in the years to come, to excavate the consecrated burial grounds of today?’106

The Irish Free State in a Global Cultural Context

The Harvard Mission work took place during a time when, Terence Brown asserts, the Irish Free State, was ‘notable for a stultifying lack of social, cultural, and economic ambition’.107 This popular idea of cultural barrenness has persisted despite being challenged in a collection of essays edited by Joost Augusteijn entitled Ireland in the 1930s.108 Auguesteijn argues that, in this decade when Fianna Fáil came to power, attempts were made to develop the Free State into ‘an entity which was not only politically but also socially, culturally and economically independent and which dealt with its citizens in a purely Irish manner’.109 This theme is explored in a diverse range of papers whose topics include the Irish language revival, the cottage schemes for agricultural labourers and the centenary celebrations for Catholic Emancipation. While archaeological initiatives are not included in his book, they can also be considered as part of this wider cultural continuum.

Native cultural achievements in the early decades of independence, including the work of the Harvard Mission, are often not recognised by cultural historians as there has been a tendency to view cultural history through the lens of the censorship laws. In Brown’s opinion, the relationship between Irish-Ireland ideology and ‘exclusivist’ cultural and social pressures culminated in the Censorship of Publications Act, 1929.110 There was also the enactment of the Censorship of Films Act, 1923. In Brian Fallon’s opinion the importance of the censorship laws has been ‘much overplayed’.111 Indeed, the analysis of native cultural achievement celebrating archaeology, literature, ancient manuscripts written in the Irish language, oral traditions, folklore, the rural way of Irish life and Catholicism has been severely limited by this methodology and has resulted in a skewed view of this period as culturally underachieving and stagnant. The placing of ‘Anglo-Irish’ literature on a pedestal as the defining Irish cultural expression of this period means that the intellectual movement of this era, which was not purely a literary one, has not been fully analysed to date. Ian Morris, an archaeologist and historian at the Stanford Department of Classics, wrote that archaeology is ‘cultural history or it is nothing’.112 The history of other forms of successful native Irish cultural endeavour likewise are essential in the writing of Irish cultural history in the early decades of independence.

According to Paul Delaney, the post-colonialist writer, Seán O’Faoláin, ‘helped to shape the ways in which subsequent generations of readers viewed the cultural history of the Free State’.113 O’Faoláin, who was not a trained historian, eschewed native achievements in favour of what he considered to be an internationalist agenda in an English-speaking world.114 The interpretation of culture through a broader lens shows how native cultural achievement was also internationalist in its scope. Cultural ideologues such as Douglas Hyde and Eoin MacNeill were very influential in the creation of a cultural identity for the independent state and the institutionalisation of native forms of cultural expression. Hyde’s ideas about cultural revitalisation in his speech was later developed by MacNeill in his own writings and in his work as a public intellectual.115 However, in a recent book, Histories of the Irish Future by Bryan Fanning (2015), exploring intellectual history through the writings of Irish thinkers, cultural nationalists such as Eoin MacNeill and Douglas Hyde are omitted. The impact of Hyde’s speech, ‘The Necessity for deAnglicising Ireland’ on the intellectual and cultural life of twentieth-century Ireland has been underestimated. The ideas contained in it were essential to the cultural underpinnings of the nationalist state. Eoin MacNeill’s academic work, as a cultural activist in the public sphere and in his cultural work abroad, was also essential to the process of state formation. His leadership of cultural institutions such as the Irish Manuscripts Commission which he cofounded in 1928, serving as its first president, was crucial to the post-colonial writing of Irish history and its establishment as a viable academic discipline in Irish universities. After the destruction of the Public Records Office at the Four Courts on 30 June 1922 during the Civil War, the importance of an organisation dedicated to the publication of original historical source materials in English and Irish was crucial.116 State cultural institutions were based on and validated by the important writings and ideas of Hyde and MacNeill, and very important cultural and scientific work such as that of the Harvard Mission was also facilitated during this period of cultural renewal.

Cultural Protectionism and Diaspora Nationalism

The much criticised censorship laws can also be interpreted as a form of cultural protectionism in this period. Peter Martin points out that Irish nationalists combined ideas about censorship with their objections to British and Anglo-American culture.117 This combination of ideas about social, cultural and racial purity of the Irish was to underpin nationalist ideology It was also an expression of fears about the degeneracy of the race reflected in social problems and a perceived decline in the physical quality of the race and in the quality of cultural production. It is also worth noting that censorship in the 1920s and 1930s was not peculiar to Ireland and can be placed in an international context.118 The agenda of the Harvard Mission to Ireland merged with the nationalist, Celtic agenda of the Irish Free State Government. Paradoxically, while Ireland was culturally and economically protectionist, her sights were fixed firmly on Europe and, to a lesser extent America, for cultural sustenance. However, native Irish cultural institutions and projects held their own in European and global cultural contexts. The Harvard Mission, which itself was an expression of Irish diaspora nationalism, involved American academics at the height of their professions, bringing international expertise to the discipline of Irish archaeology. The popular idea of insular self-obsession is belied by the fact that international expertise was actively sought by the Irish Free State Government. Examples of this include the seeking of a keeper of Irish Antiquities with European archaeological expertise, such as the German, Walther Bremer, an expert in German archaeology and Celtic culture who was appointed in 1926; Adolf Mahr, the Austrian Celtic archaeologist, succeeded Bremer in 1927 as Keeper of Irish Antiquities and was later appointed to the position of Director of the National Museum in 1934; American/Harvard expertise in archaeological methodology and physical anthropology was embraced with enthusiasm; Danish expertise was acquired for the Quaternary Research Committee; and Scandinavian expertise was sought for the establishment of the Folklore Commission. Some important senior state jobs in the economic and cultural sector in the Irish Free State were held by Germans during the 1930s. Heinz Meking was the chief adviser with the Turf Development Board; Ludwig Mühlhausen was a Professor of Celtic Studies; Colonel Fritz Brase was head of the Irish Army’s School of Music; Otto Reinhard was Director of Forestry in the Department of Lands; Robert Stumpf was a radiologist at Baggot Street; Friedrich Herkner was Professor of Sculpture at the National College of Art; Friedrich Weckler was chief accountant of the ESB from 1930 to 1943; and Oswald Muller Dubrow was Director of the Siemens-Schuckert Group, which built the Shannon Hydroelectric Scheme.119 A dam and power station was constructed at Ardnacrusha, Co. Limerick on the River Shannon and the first national electrification grid in Europe was created. It was opened by W.T. Cosgrave in 1929. Trips to the Shannon development were offered by Great Southern Railways.120 This massive undertaking cost the state £5.2 million, an astronomical sum at the time.121

Political progress was expressed through scientific and technological progress and the scheme became ‘a potent symbol of a new post-Treaty Ireland, as an indigenous source of energy to power industrial development’.122 The view was expressed in the Irish Statesman that this project reflected the ‘attitude of mind proper to a self-governing nation’123 This attitude of mind was also evident in the paintings of the artist, Seán Keating. Keating was commissioned to create a series of paintings on the theme of ‘the dawn of a new Ireland’, to celebrate this industrial achievement. One of the most famous of these paintings was Night’s Candles are Burnt Out, first exhibited at the Royal Academy in London in 1929.124 Some of Keating’s paintings were also sent as part of a cultural package which centred on the collections of the National Museum of Ireland to the Chicago World Fair in 1933 and 1934.125 In a New York Times Magazine article, ‘The Shannon stirs new hope in Ireland,’ it was noted that it was ‘the outward sign of transforming forces liberated by the Treaty settlement that are destined to create an Ireland that need no longer turn wistfully to the past for its golden age’.126 However, nationalist governments in Ireland continued to look to the future through the perceived achievements of the Irish nation expressed through cultural production during its past golden ages, Celtic and Christian. During the construction of the Hydroelectric Scheme there was much contemporary debate about the preservation of national monuments. One example was the contested treatment of St. Lua’s Oratory, a medieval ruin which was moved from Friar’s Island to the grounds of St. Flannan’s Roman Catholic Church in Killaloe.127

Catholic Identity and Material Culture

The identity of the Irish Free State as Celtic and Catholic was important to the first two nationalist governments. The Cosgrave government organised the centenary of Catholic Emancipation in 1929. The de Valera government oversaw the Eucharistic Congress of 1932, described in the Round Table journal as ‘a hosting of the Gael from every country under the sun’. There was much appropriation of material culture for Catholic purposes in the celebrations of the Eucharistic Congress in 1932. The congress became ‘a culminating event in the Irish national struggle’, in which images of the past played an important role.128 For example, replicas of round towers were erected at College Green and St. Stephen’s Green. St. Patrick’s bell was borrowed from the National Museum for use in the Pontifical High Mass on 26 June 1932.129 The sound of St. Patrick’s bell at the event was described by the Catholic writer, G.K. Chesterton, as follows:

It was as if it came out of the Stone Age; when even musical instruments might be made of stone. It was the bell of St. Patrick, which had been silent for 1,500 years. I know of no poetical parallel to the effect of that little noise in that huge presence. From far away in the most forgotten of the centuries, as if down avenues that were colonnades of corpses, one dead man had spoken. It was St. Patrick; and he only said: ‘My master is here.’130

The association of St. Patrick’s bell exclusively with Catholicism in this way was an appropriation of an archaeological artefact for use in the construction of an identity for Ireland which was different culturally and socially from their Anglo-Saxon neighbours. In his address at the Eucharistic Congress at a state reception at Dublin Castle in honour of the Cardinal Legate, de Valera stated that ‘At this time when we welcome to Ireland this latest Legation from the Eternal City, we are commemorating the Apostolic Mission to Ireland, given fifteen centuries ago to St. Patrick, Apostle of our Nation’.131

The Eucharistic Congress was described as ‘a flashpoint in the formation of a specific Irish Catholic identity’.132 More than a million people attended masses in the Phoenix Park over five days. Adolf Mahr was commissioned to write a book, Christian Art in Ancient Ireland: Selected Objects Illustrated and Described, for the event. It was presented by de Valera to the Cardinal Legate at Government Buildings on 23 June 1932.133 Volume II of the book was completed by Mahr’s successor, the archaeologist Joseph Raftery, in 1941. In his review of Mahr’s book, Cyril Fox wrote in 1932, that ‘we warmly congratulate the Government of Saorstát Éireann on this new evidence of their appreciation of “the vital function which art has in the life of a nation.”’134 This viewpoint about art and the nation provides an interesting counterpoint to that espoused by Brian P. Kennedy on the importance of art in independent Ireland.135 The cultural revival, prior to 1922, was infused with the Protestant ethos of W.B. Yeats, Lady Gregory and others but was supplanted by a catholicisation of culture in the newly independent state where ‘Celtic’ was assumed to be synonymous with Catholic. Indeed, Celtic Art was a politically hot topic as it was considered essential to the identity of the state and the prospect of discovering valuable Celtic objects was a core ambition of the Harvard archaeologists. While Hyde advocated an inclusive religious ethos, the cultural vision of the first two nationalist governments under Cosgrave and de Valera was a Catholic one. As modernist thinking did not necessarily take the form of secularism in the interwar period, expressions of Catholicism fitted the broader cultural regenerative model, driven by nationalist ideology.

This cultural blossoming became imbued with the catholicity of the newly independent State. The ‘Early Christian Period’, in archaeology, for example, came to be seen as exclusively Catholic. This is also reflected in the setting up of the Academy of Christian Art in 1929 which was under the patronage of Saints Patrick, Brigid and Columcille. Article iv of its constitution stated that ‘For reasons of doctrine and ritual the academy shall include none but Catholics’.136 In 1922, the Central Catholic Library in Dublin was established.137 It was de Valera’s view that ‘the Irish genius has always stressed spiritual and intellectual values rather than material ones’.138 This emphasis on the spiritual was also expressed in the foreword to the catalogue, The Pageant of the Celt, performed at the Chicago World Fair in 1934. One example of this type of sentiment included the statement: ‘We who have seen our world wrecked on the reefs of material philosophy must seek our own rebirth and the salvation of our heirs in the beacon light of that Celtic philosophy which in other days saved the world for Christian ideals’.139 The Pageant of the Celt, narrated by Micheál MacLiammóir, covered a 3,500-year period of Irish history in nine scenes, from the arrival of the ‘Milesians’ in prehistory to the 1916 Rising.140 It was reported in the Chicago Herald that John V. Ryan, President of Irish Historical Productions, Inc., and a Chicago attorney, composed the ‘richly poetic version of Ireland’s history’.141 The objective of the pageant was ‘to present a spectacle worthy of their Celtic past, and reveal to Americans of Celtic tradition a glimpse of their rich racial heritage’.142

A Century of Progress in Irish Archaeology

An official Irish Free State exhibition was displayed in the modernist Travel and Transport building at the Chicago World Fair in 1934, the theme of which was ‘A Century of Progress’.143 This was organised by Daniel J. McGrath, the Irish Consul-General in Chicago and centred around antiquities in the National Museum. An ‘impressive effort’ involved the collaboration of the National Museum of Ireland, the Royal Irish Academy and the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland to present ‘A Century of Progress in Irish Archaeology’.144 Artefacts and copies of them included ‘Celtic’ cultural items from the Early Christian Period and ‘Celtic’ cultural items from the Early Bronze Age. Artefacts discovered by the Harvard Mission archaeologists included a cast of the Viking gaming board and an electrotype of a bronze hanging bowl from Ballinderry 1 Crannóg, Co. Westmeath. The antiquities were considered at the time to be very important because of ‘the all-European and indeed, universal importance of Irish archaeology’.145 Editions of the Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland and the Journal of the Co. Louth Archaeological Journal were displayed. Also exhibited were popular guides on archaeological sites; a copy of the National Monuments Act, 1930; the ‘List of scheduled monuments in the care of the Commissioners of Public Works’; and some Office of Public Works (OPW) Annual Reports with descriptions of famous sites such as Glendalough, Clonmacnoise and the Rock of Cashel. A photographic album compiled by the Dublin optician and antiquarian Thomas Holmes Mason, MRIA, contained photographs of the well-known archaeological monuments in their natural settings including Newgrange, Dowth, Dun Aengus, the Skelligs, Glendalough, Monasterboice and Clonmacnoise. The archaeological exhibit was part of a wider cultural package which reflected the ideas and values and aspirations of the Irish Free State. Included were facsimiles of the Book of Kells and the Book of Durrow; stills from the film Man of Aran, paintings by Jack B. Yeats, Paul Henry and George Russell (AE), books and cards from the Cuala Press, tapestries from the Dún Emer Guild and books in the Irish language.146

The correlation of race, religion and cultural expression was typical of the period. The idea that a pure race would produce a pure cultural product was an idea common in archaeological discourse. MacNeill’s academic tour of universities in the United States in 1930 not only attracted the Harvard Mission to Ireland, but the Mission’s work in turn gave scientific credence to Irish archaeological and medieval historical scholarship. MacNeill, who can be seen as a cultural ambassador for Ireland, was working hard to encourage the development of Celtic Studies in the United States.147 Celtic Studies became an important conduit for the post-colonial desire to re-establish cultural connections within the diaspora as a way of gaining a cultural and, therefore, economic, foothold on the world stage.

A World Centre of Celtic Culture

Douglas Hyde had expressed his gratitude for the interest of American academics in ‘everything concerned with us – history, archaeology and language’.148 He corresponded regularly with the American Celticists including Fred Norris Robinson, Arthur L.C. Brown and Roger Sherman Loomis. He also kept an autographed photograph of Theodore Roosevelt, a Celtophile, on the wall in his study.149 In 1930, Eoin MacNeill was invited to tour some American universities by Professor Arthur L.C. Brown, of Northwestern University; Professor J. Peet Cross, of Chicago University and Professor Robert D. Scott, of the University of Nebraska.150 He described these scholars as ‘of the highest reputation on both sides of the Atlantic as authorities on the mediaeval literatures of Northern and Western Europe’.151 During his tour, he visited Harvard, Columbia, New York, Yale, Fordham, Notre Dame, and Northwestern University in Chicago. At that time Harvard and the Catholic University of America were the two institutions at the forefront of the development and promotion of Celtic Studies in the United States. Fred Robinson of Harvard was central to the development of Celtic Studies at Harvard and its increasing importance in the cultural life of North America.152 When he arrived in New York on 2 April 1930 MacNeill was met by detectives and the police as political threats had been made against him.153 His first lecture was on early Celtic institutions and law which was delivered at New York University (NYU) on 2 April 1930. A dinner was hosted in his honour by the American Irish Historical Society of New York and the Law School of New York University. The American Irish Historical Society (AIHS) was founded in 1897 for the purpose of correcting the perception of Ireland’s role in American history.154 By the 1930s this perception was beginning to change. Other speakers at the dinner included Daniel F. Cohalan, who took an active role in the AIHS. Cohalan was the son of an Irish immigrant who left Cork at the height of the Famine in 1847. He had a lot of political influence and was regarded as the ‘leader of the Irish race in America’.155 Prior to his meeting with Eoin MacNeill, Cohalan had met with important cultural and political figures including Douglas Hyde, Patrick Pearse and Roger Casement. He served as President of the Board of Directors of the influential Irish-American newspaper, the Gaelic American from 1903 and was co-founder of the Sinn Féin League of New York with John Devoy in 1907. Cohalan was leader of the Irish-American organisation Friends of Irish Freedom (FOIF) which was launched a few weeks prior to the 1916 Rising. He supported the Irish Treaty of 1921. MacNeill revealed in his speech in the NYU Law School that ‘he did not believe in impartial national histories’ and that he was ‘willing frankly to admit his inability to write an impartial history of Ireland’.156 This admission gives an insight into his philosophy of history, his nationalist perspective of the past and the expectations of his Irish-American audience.

In 1931 Professor John L. Gerig announced a plan that Harvard and Columbia universities would join together to establish a university in the Scottish Highlands ‘to serve as a world centre of Celtic culture and to preserve the Scottish and Irish dialects from the extinction threatened by the rapid advance of English as a world tongue’.157 Gerig taught Celtic for many years at Columbia University and had been a student of d’Arbois de Jubainville, the famous nineteenth-century French Celticist.158 He wrote to E.J. Gwynn, Provost of Trinity College Dublin, that the plans for the university should ‘emphasise to the Scots and the Irish the role of America in world culture’. E.J. Gwynn replied that ‘The real centre of Celtic studies, ought, of course, to be [….] in Dublin’.159

In the Gaelic American of 27 June 1931 it was reported that Gerig bemoaned the lack of endowments and special chairs for Gaelic studies and the fact that there were ‘no special professors to devote their whole time to the racial heritage of the Gael’.160 For many years the Gaelic American newspaper had highlighted ‘the neglect of Americans of Irish blood in safeguarding their cultural heritage and their backwardness in this respect as compared with other races that make up the cosmopolitan population of America’.161

Gerig’s ‘arresting plea’ for a campaign to stimulate interest in Celtic culture in America was discussed in an article published in the Irish Independent on 6 June 1931. The view was expressed by the author that ‘Ireland was once the centre of learning for Europe. There is no reason why it should not again become the fountain of culture at least for the children of her own race’.162 In the Gaelic American newspaper, 27 June 1931, it was reported that the quality of research work was recognised by leading Irish scholars and colleges, and that this had ‘inspired the hope that America will take the place of Germany in this field of endeavour’. E.J. Gwynn strongly approved of American interest in Celtic Studies. He wrote to Gerig on 10 November 1930 that ‘it is a great satisfaction to know that the decline of Celtic scholarship in France and Germany is being counterbalanced to some extent by the increasing interest shown in the universities of U.S.A’.163 James McGurrin, President-General of the AIHS of New York, in a letter published in The Irish Times, 21 June 1934, acknowledged the fact that the growing interest in things Celtic had produced a large body of research work, ‘and its highest practical expression is seen in the work of the Harvard University Archaeological Mission’.164 After his American tour, Eoin MacNeill suggested that in order to promote a knowledge of Irish national culture, both past and present, special Irish cultural sections in US public libraries and in the libraries of schools, colleges and universities should be set up.165 J.P. Walshe, Secretary at the Department of External Affairs, advised de Valera on 5 October 1937 that ‘the time has come to interest ourselves directly as a Government in what we might call, for want of a better expression, cultural propaganda in the United States’.166 It was his view that it would be money well spent as it would increase the number of tourists. In 1936, a proposal was made to establish in the US an institute similar to the American-Scandinavian Foundation.167

In 1940, a School of Celtic Studies and a School of Theoretical Physics were combined in de Valera’s modernist project – the Institute for Advanced Studies in Dublin. It was de Valera’s ambition that the institute would be a world centre for Celtic Studies and he modelled it on the Institute for Advanced Studies at Princeton University. In a Dáil debate on the Institute for Advanced Studies Bill, 1939, de Valera had explained that ‘at the moment we have the leadership of the Celtic nations in so far as we alone of these have a government which can foster, with special interest, the prosecution of such studies’.168 The purpose of the school was to edit and publish material relating to early modern Irish and to produce grammars and dictionaries. De Valera explained what he meant by the term ‘Celtic’:

By ‘Celtic,’ I want it to be clearly understood, we mean more than merely Irish studies. We are thinking of the related Celtic nations and we are anxious to hold our place, as I indicated at the start, as the chief centre for Celtic Studies. There was a time when the centre for Celtic Studies was outside this country but, as time goes on, it is becoming more and more apparent that this country is the natural centre for Celtic studies and we have the men for the work.169

Timothy Linehan of Fine Gael objected to the expenditure on the proposed institute and the abuse of the term ‘Celtic’, stating that ‘you can justify any expenditure of money in this country, you can justify anything in this country by making it Celtic, Gaelic, Irish or national. Anybody who would attack this Bill probably would be attacked all over the country as anti-national and anti-Celtic’.170 The School of Celtic Studies at the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies did not include archaeology among its disciplines. It is likely that there were political reasons for this.

Daniel A. Binchy, a scholar of Irish linguistics and early Irish law, and later a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, had been appointed as the first Chairman of the Governing Board of the School of Celtic Studies in 1940. He had served on the Board of the Irish Folklore Commission with Adolf Mahr. Binchy and Mahr had ‘diametrically opposed views on Nazism’.171 These political tensions had affected Binchy’s attendance at meetings of the Board. He had served as an Irish diplomat in Germany between 1929 and 1932 and later wrote articles which were very critical of Hitler and the Nazis.172 The study of prehistory was getting a bad name in Germany because of the abuse of the discipline by the state.173 Binchy, no doubt, feared that something similar could happen in Ireland considering that an influential Nazi had been director of the National Museum until 1939. By 1946, the Professor of Celtic Archaeology at UCD, Seán P. Ó Ríordáin was complaining about the ‘limited number engaged in the pursuit of archaeology’ in Ireland and made an appeal for financial aid for research, ‘whether it be provided through the Universities or through a special research institute. It is hoped that the State will prove as generous in this as it has been to other intellectual disciplines’.174 However, this was not to be and no archaeological institute was established.