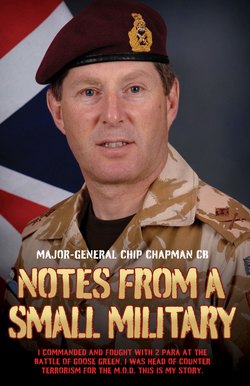

Читать книгу Notes From a Small Military - I Commanded and Fought with 2 Para at the Battle of Goose Green. I was Head of Counter Terrorism for the M.O.D. This is my True Story - Major-General Chip Chapman - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

JOINING ‘THE REG’: P COMPANY AND PARACHUTING

ОглавлениеThere is no point being a member of the Barbie Club if you are a fan of the fantasy game Warhammer. The Parachute Regiment is Warhammer on steroids. It also believes itself to be – and it is – an elite organisation. Every man in the regiment, officer or soldier, has a bond that is sealed in the privation and shared experience of having had to undergo the same rigorous selection to earn and wear the Red Beret. Part of that is inculcation into the ethos of this particular ‘band of brothers’. It is best described by Field Marshal Montgomery’s famous quotation, which almost all paratroopers know off by heart:

What manner of men are these who wear the red beret? They are firstly all volunteers and are then toughened by hard physical training. As a result, they have that infectious optimism and that offensive eagerness which comes from physical well-being. They have jumped from the air and by doing so have conquered fear.

Their duty lies in the van of battle; they are proud of that honour and have never failed in any task. They have the highest standards in all things, whether it is skill in battle or smartness in the execution of all peacetime duties.

They have shown themselves to be as tenacious and determined in defence as they are courageous in attack.

They are, in fact, men apart – every man an Emperor.

Before you can become an emperor, you have a period of apprenticeship: a rite of passage. For the Parachute Regiment this is formed by Pre-Parachute Selection (PPS), more commonly known as ‘P Company’.

Not all pass, and the denouement after the conclusion of all the selection events is brutal. Each person stands up as an individual and is told simply in one-word terms, ‘pass’ or ‘fail’. There is absolutely nothing in between, and no discussion of the why or wherefore of the decision. I’m not too sure if this ‘men apart’ band has now been broadened to include ‘men and women apart’. It should, so that all genders have the equal right to pass if they are good enough, and fail if they are not good enough. That is and should be the standard: without any social engineering to take account of physiological or other factors, because the last time I looked, the enemies on the battlefield do not place much credence in social engineering. They merely want to kill you.

It is probably bleeding obvious that the first requirement is to be fit. But there is more beyond that: mental determination to carry on when the going gets tough, and for officers to show leadership and not to shun the limelight, merely seeking to ‘get through it’.

Cleanliness – both of clothing and body – really was next to godliness. Godliness only involved two things: fitness and determination. We all knew that God was Airborne: it was drummed in to us. Bullets and shrapnel may not take fitness into account, but many soldiers’ lives have been saved after they have been wounded because they were fit, and had the mental attitude not to give in.

These were the final days for the young officers on the course when they would have no overt leadership or command responsibility. You only needed to know two mantras and one quotation to sustain you and to help you through:

A thoroughbred horse runs until its heart gives out.

We have it easy compared to the French foreign legion.

No one actually expected us to die because our hearts had given out, but they certainly did expect us not to give up. By the end of the first day, the 51 who started the course had been whittled down to 46. Five were already not godly enough. They had not driven through the ‘no pain, no gain’ expectation to win the prize of their red beret, or as G B Shaw put it: ‘The most intolerable pain is produced by prolonging the keenest pleasure.’3 We wanted that red beret.

P Company had a ritualistic feel to it. Each day of the two-week ‘beat-up’ prior to the selection week began the same way with the Army Basic Fitness Test (BFT) along Queens Avenue in Aldershot. The BFT was a squad run for one-and-a-half miles followed by a ‘best effort’ one-and-a-half miles back. The rule of thumb was that anyone who could not complete the BFT in less than nine minutes, in their Directly Moulded Sole boots and puttees tucked in to their green lightweight army trousers, would struggle to pass. It was cannily accurate.

Each candidate wore their army issue red or white PT vest with their name written across the front. In some cases, this would be the front and back to cope with officers with double-barrelled names such as Lt Stewart Larter-Whitcher or Lt Nick De Tscharner-Vischer. It was probably a good thing that the officer with probably the longest name in the army – Patrick Elrington O’Reilly-Blackwood Davidson-Houston – never attempted P Company, for there would have been a problem finding enough black ink to write it on any shirt. I once went to a meeting where a fellow officer (the current Chief of Defence Staff, General Sir Nick Houghton, when he was commanding 38 Brigade in Northern Ireland) briefed that his oral report would be of greater brevity than PEO’R-BD-H’s name. I could almost imagine Patrick Elrington O’Reilly-Blackwood Davidson-Houston having to ‘mill’ (a form of boxing but without the Queensberry Rules) against Christopher James Piers De Lukacs Lessner De Szeged. I imagined them trading blows, with each blow leading to a letter of their respective names falling from their PT vests until we were left with an exhausted winner and the pronouncement that they had fought a good fight and the winner was declared by the ‘last letter standing’.

We would change into our army issue blue shorts and black PT shoes for gym sessions. The equipment issued to the British army has historically come in for a lot of criticism, but I have to commend the cotton blue PT shorts for their ruggedness and longevity. I still wear those shorts 32 years later. They are still working well. They may not have a designer logo on them but they sure are tough wearing. I even wore them in a race in 2012 while in Tampa. The whole-life cost of those shorts is something to behold; they represent real value for money. The same could not be said for our PT shoes. In reality, they were black plimsolls; exactly the same as worn as a young child in junior school. Soldiers really did complete half marathons and suchlike in these plimmys, even into the 1980s. It was no wonder we had so many lower-leg and foot injuries.

The conclusion of each day of P Company led to a ritual: officers would head back to the officers’ mess to indulge in a soothing Radox bath in an attempt to get some of the stiffness and pain from their aching limbs. In those days, ice baths were unheard of. In the evenings we drank nothing more at the bar than an orange juice and lemonade. Alcohol was verboten. It was little wonder that an orange juice and lemonade was ordered at the bar by its own official name. You would merely ask for a ‘P Company’ and the fizzy yellow concoction would appear.

Our administrative requirements as officers were simple. On the ‘things to do/things to buy’ list during P Company, the daily and weekly requirements were no more complex than:

| Wash kit |

| Buy Vaseline (for nipple rash) |

| Check kit in drying room |

| Clean boots and plimsolls |

| Press kit (lightweight trousers, PT shirts, puttees) |

| Adjust webbing and rucksack (to save on further applications of Vaseline elsewhere on the body) |

| Check alarm timing on clock radio |

| Buy Radox, foot pads, glucose drinks, energy tablets |

The set events in Test Week were designed to simulate various portions of an airborne battle. I’m not sure how ‘milling’ takes its place within the context of an airborne battle. Milling is like boxing, but one is not allowed to box. It is pure fighting. The object is to land as many blows on your opponent for as long as possible over a two-minute period in order to show tenacity, courage and determination. If one is knocked down, there is merely a brief pause while one gets up to start the battering (one way or another) again. I still recall the name of the opponent I fought – Baxter from 9 Parachute Squadron Royal Engineers. I was given as the victor for my bout. Fortunately, I was up against someone of comparable weight, so the bout was evenly matched. If the P Company staff did not like you, or wished you to be taught an early lesson, the weight differentials could be what one might term ‘unfair’. Acceptance of this unfairness was expected. After all, if we were to be clever in warfare we wanted and should expect an unfair fight. In most cases, and using the principles of war, this unfairness should be in our favour. As you will see throughout this book, it was often the other way around!

I believe that in the modern era of ‘health and safety’ and ‘duty of care’, the current P Company candidates are now allowed to wear head guards during the milling. We were protected only by our blue army shorts and white PT vests. The latter could be problematic, as it could quickly become bloodied. One was expected to turn out in pristine white PT vests sans blood for follow-on activities. Buying additional PT vests to lessen the load on the overworked washing machines was a sound policy in lessening the groundhog-day simplicity of the ‘things to do’ list.

Some people fell quickly by the wayside, not being able to complete the high bars confidence course successfully. The piéce de resistance of this event was the shuffle bars test 30ft above ground. This consisted of shuffling along a couple of parallel scaffolding bars, with the added bonus of being required to delicately raise your feet over the scaffold brace about half way along in order to proceed to the end, then bend over and touch your toes while screaming out your army number. The whole episode was a slight illusion; if you fell off there was a safety net somewhere below. But the illusion worked. There were people whose fear of heights paralysed them. There were people whose fear of heights was overcome by their determination to succeed. Those who were paralysed were instantly given the red card: there was to be no pass or fail for such soldiers or officers. They were, in the words no one ever wants to hear, Returned to Unit or RTU’d. If this was an officer who had been sponsored through Sandhurst by the Parachute Regiment he would now be instantly looking for another regiment to accept him. He was a casualty of peace.

Military marching with heavy weights is part of the Parachute Regiment ethos. They are good at it. Marching in the Paras is known as tabbing, which is supposed to be an elongated acronym for ‘tactical advance to battle’ (something I did not know for about 10 years). The Royal Marines’ equivalent is known as yomping. You will never get anyone from either organisation using the vernacular of the other; that would be akin to a criminal offence. Yomping is like tabbing but much, much slower. The Royal Marines will, in the competitive world of elite forces, tell you that it is the other way around.

Marching (tabbing) is therefore a core part of P Company. Two of the test events were the 10-miler, with a 10lb rifle and 35lb pack, to be completed in one hour and 45 minutes, and a 14-miler on the South Downs Way. Part of the start day ritual would be the weigh-in of all our backpacks (bergens) to ensure that no one could cheat on the weight. The only ones allowed to do that were the instructors: the clipboards they carried weighed more than their packs (but they did do the distances day in and day out, and so the toll on their knees over a two-year posting made this concession understandable). Although the location of P Company has changed over the years (it is now in Catterick, North Yorkshire, since Depot Para in Aldershot closed under earlier defence cuts), the style and pain remains the same. You, dear reader, now have your own chance to experience the 10-miler: there is now an annual ‘Paras 10’ charity event run in Catterick, Aldershot and Colchester. You can now pay to be put through the agony and hills of Catterick. The concession is that you can do this with or without a bergen – and you get a medal.

The key requirement in all the test marches was to stay with the main group. If you began to fall back, you would always be chasing the error in attempting to catch or keep up with the group. And it would begin to eat at you mentally as you crossed the features seared into our memories: Hungry Hill, Flagstaff Hill, Miles Hill, Seven Sisters (why are large sequences of hills always called sisters or, as in Australia and Cape Town, the 12 apostles?), Concrete Hill and finally, what sounded like the luxury of a valley but was in reality the energy-sucking glue of Long Valley. There were a lot of hills. If you had fallen behind, the worst thing would be to think you had caught up during one of the quick water stops, only for the group to set off again, once more beginning to leave you behind. Being ‘off-pace’ was weakness and therefore not tolerated.

Two other endurance events on the plat du jour of P Company were the Stretcher Race and the Log Race. Both of these are universally hated for the pain they inflict. The Log Race is designed to simulate bringing an artillery gun or large anti-tank weapon into action. This is a good idea, although I cannot think of too many battles – no, change that to ‘I cannot think of any battle’ – where a bunch of men have had to run seven miles to bring an artillery piece into action. The Naval Gun Race that used to be so popular at Earls Court in the days of the Royal Tournament was conducted over the length of two football fields and simulated a Boer War naval brigade engagement. Maybe our log race was designed to simulate trying to get the weapons in to Arnhem from the 1944 drop zones, for the distance involved was not dissimilar to this event.

In both the log race and the stretcher race, the most heinous crime was to come off the log or the stretcher. When it was your turn to be part of the carrying party, you were to be fixed to it no matter how painful or tired. To ‘jack’, the colloquial shortened version of to ‘jack something in’ (cease doing something), would once again lead to a fail. It showed a lack of determination and guts. The log was a spruce pine about 14ft long. The carrying handles were not designed by Conran, but by the Marquis de Sade. They were no more than thick ropes with a toggle on the end. They bit in to your hands, and with a number of log runners on the left and right, had the ergonomics of a dysfunctional attempt at sculling in an Oxford v Cambridge boat race – but one that you tried to row in once the boat had overturned.

The stretcher race was a similar distance and the stretcher too had been designed by the Marquis. With shortened scaffolding poles of tubular steel and a flat top, it resembled a stretcher but it was made of heavy metal. In the history of medicine there has been no example of a stretcher made of scaffolding poles – but our test was not designed to replicate medicine, more the pain of having teeth pulled without an aesthetic.

The assault course and steeplechase events (muddy deep water to wade through as routine and guaranteed to sap your energy) almost completed the P Company events. The most famous horse-racing steeplechase is the Grand National at Aintree. The average winning time is a touch over nine minutes (‘Mr Frisk’ holds the course record with 8:47.8 for those about to go to the pub quiz after reading this chapter). Our steeplechase was scored on points rather than position. You only got six points for 18 minutes and 30 seconds of two miles of soft-going agony, and like Aintree it was two circuits. The preview of running the steeplechase was rather like a jockey doing his own notation at Aintree:

Attack the first water obstacle by going to the left.

Attack the second by going left.

Jump all poles; trying to clamber over them will slow you down.

Large pole: keep right, watch the second ditch.

Single pole: shallow, watch your ankle on landing.

Run and run until your heart gives out.

The assault course was more like Aintree in relation to its timings. A scoring mark of six points only required you to complete the course in seven minutes and 30 seconds. Considering that most of the soldiers could run a mile in somewhere around six minutes, this was no ordinary assault course. Neither were the instructions. They were far simpler than the steeplechase: ‘Always run and attack all obstacles.’

The final 14-mile South Downs march was a picnic after the previous events. My reward came when we were back in base and assembled in a silent room. I was asked to stand and was told, ‘Pass’. I was now the official proud owner of a red beret.

There were two interesting cultural bookends either side of P Company. Just prior to the start of P Company, I attended an army football dinner. The speaker was the first England football manager from 1946 to 1962, Sir Walter Winterbottom, who gave an insight into the pressures of being a top class football manager.

At the conclusion of P Company, I travelled to Blackpool to stay with a university friend for the weekend. I had never been on such a depressing train journey. The coaches were for a ‘holiday special’: two words that did not fit easily together in any trip to Blackpool in the early 1980s. The average age of those on board was about the same as the top speed of the train, with the packed ranks heading to the north to re-live the memories of their youth. Blackpool is as good a reason as you can find for cheap air travel.

I hope the good folk of Blackpool will forgive my memories of the place, but its heyday was rather like the era of the speaker we turned up to see at a country club – the legendary Stan Mortensen. As every soccer-loving fan will know, he scored a hat-trick in the 1953 ‘Matthews Final’ – Blackpool’s 4-3 defeat of Bolton Wanderers. I sincerely hope that that, like the modern Blackpool football team, the town is once more enjoying moments in the regenerative sunshine, as they did under that newest of football philosophers, their manager Ian Holloway. But he has now moved elsewhere, and my memories of Blackpool may cast me in the same treacherous mould as those who turn their backs on their football teams. Football is not, despite the pressures that Winterbottom and Mortensen spoke of (and both served in the Second World War), a matter of life and death. What I would experience in 1982 most certainly was.

With P Company done with, it was time to complete our jumps training at RAF Brize Norton. The sun seemed to shine relentlessly. It was a glorious summer, and the final few weeks that the officers on the course would have with no responsibility before they would be unleashed on their unsuspecting battalions. In many ways, those halcyon summer days put one in mind of the seminal work on the RAF during the Second World War – Richard Hillary’s The Last Enemy.4 For some, this notion of a halcyon summer before a storm would become a reality: one of our fellow parachuting students was Captain John Hamilton who had just passed SAS selection and was also completing his jumps training. He was killed in the Falklands War almost a year later.

The on-camp cinema at Brize Norton showed the film A Bridge Too Far, and all the soon-to-be-qualified paratroopers would rush to see it. It had been released in 1977 and it was now 1981, so either the film was on a continuous loop, the most successful and longest-running film in history, or recycled with every parachuting course that trooped through the base. I favour my final theory.

It may seem curious that in a parachute course that lasted for four weeks, one was required to complete only eight jumps, with and without equipment, and by day and by night. Military parachuting is something that does require an almost automatic and learnt response, for time in the air in which to correct errors is precious, and the decision-making needs to be swift.

While it is rare these days for people to be killed in military parachuting, the numbers of jumpers in the air at any one time can be vast – all potentially occupying, or attempting to occupy, the same air space. Air space, along with time, is a precious commodity, for an ‘air steal’ – where someone glides across the top of your canopy – causes your own parachute to deflate and collapse. Should this occur the laws of physics apply, and you have the aerial buoyancy of a stone. Plummeting to earth occurs unless corrective action is taken – and quickly.

The first weeks are conducted in a large hanger in either flight swings, or on rubber mats, learning, relearning and reinforcing what has already been learnt. It is little wonder that the motto of the Parachute Training School is ‘Knowledge Dispels Fear’.

Everyone remembers their first jump. It occurs at Weston-on-the Green, near Oxford, overlooking the A40. Four men rise from the ground in a cage with a large barrage balloon inflated above them. This initiation will be the balloon jump. It is eerily quiet as the jumpmaster declares, ‘Up 800, four men jumping.’

A winch cranks into gear, and a soft, swaying journey takes place. Sergeant Martin, the parachute jump instructor from the RAF, does a supreme man-management job in the ascending balloon to take our minds off the altitude. The winch stops. We are 800ft above the ground. The balloon blows gently, and the first novice is called to the door.

Me: ‘Red On’.

Hands swiftly close on the top of the reserve parachute.

‘Go.’

A leap occurs into the air.

‘1,000, 2,000, 3,000, CHECK CANOPY.’

You look up in anticipation that above your head is a growing envelope of silk attached by parachute cord to the webbing straps that secure the harness via your ‘risers’ to your back. The inside of the canopy is a welcome sight. The noise as the chute opens reminds me of the wind billowing through bed linen on a washing line from my childhood days. The absence of a canopy leads to the instant deployment of the reserve chute – rare on a balloon jump. You quickly separate the risers to peer above, beneath, and around to assess that you are in clear air space. You are now a parachutist. You smile with glee, and then keep all body parts tightly together to conduct a safe roll as you come in to the ground. You smile after you collapse your parachute and roll it up. It will be repacked for a future descent. Your smile is now ear-to-ear. You are happy. You are on your way to earning your wings and become part of Airborne Forces. And someone has paid for you to have that smile.

As more descents occur, further complications are added. These include aircraft, equipment, people trying to invade the same air as you, and the night. Additional vocabularies are added. An unclean aircraft exit inevitably leads to a few spins and the authoritatively shouted informative instruction to those around to ‘STEER AWAY, I’M IN TWISTS!’ This is rightly shouted in capital letters, for until one has managed to kick out of twists, the ability to control any movement of the canopy is severely constrained. Other jumpers must steer away, for you are at that moment a dangerous hazard.

‘Twists’ also mean you cannot lower your equipment. Military parachuting requires you to carry all that you need with you. The rucksack, which will be carried once on the ground, is attached by a device to the legs. Once in clear air space, you must lower your equipment as quickly as possible; failure to do so will almost inevitably lead to broken legs, as there will be no ability to turn off the limbs for any sort of landing. Watching men fail to lower their equipment due to entanglements with other parachutists (another not-to-be-recommended technique or procedure for landing) or other problems will inevitably lead to screams from those already on the ground to ‘LOWER YOUR EQUIPMENT!!’ The capital letters will get bigger as the parachutist gets closer to the ground. You assume that reserve parachutes have already been deployed in the first few seconds after an entanglement: entwined parachutes look more like a basket of laundry. They also have the properties of a bag of laundry and not of a parachute. Deployment of the reserve parachute must be a reflex action. It almost inevitably is.

The third jump saw us jumping at the maximum permitted wind speed of 13 knots. The fourth was at night. Sixty exited our plane; three were injured as they attempted to distinguish between the darkness of the night and the darkness of the ground. They all suffered ankle fractures after attempting to do a ‘pointy toes’ impression of a three-year-old having a first ballet lesson. They had forgotten ‘never anticipate the ground; keep your feet and knees tight together’.

Jumps five, six and seven all took place on the same day. They required me to revisit my ‘administrative requirements matrix’ and specifically to ‘check alarm timing on clock radio’. We mustered at four in the morning for increasingly complex jump sequences with both equipment and multiple parachutists in the air from both port and starboard doors of the Hercules aircraft as we practised simultaneous stick exits. On 19 June 1981, I completed my eighth and final qualifying jump. I now had my wings to go with the red beret.

Military parachuting can be dangerous. The most senior non-combat death since the Second World War is Brigadier O’Kane. He died in a parachute malfunction whilst commanding 44 Parachute Brigade (Volunteer). A rather unfortunate exercise name was the ill-fated DYNAMIC IMPACT. This battalion drop by 1 PARA in Sardinia led to around 28 serious casualties with the paratroopers exiting in high winds into a badly reconnoitred drop zone strewn with debris. The most poignant and frequent sound you hear on a DZ, even if it is pitch black, which only serves to amplify the effect, is the scream of ‘MEDIC!!’ It comes from those who have, in the popular vernacular, ‘creamed in’ and become casualties who will not walk off the DZ under their own steam. All men want to get out of the plane as quickly as possible, for RAF pilots have to fly at low level. This entails them flying at 200ft to simulate evading radar. The buffeting this provides to the paratroopers inevitably leads to sustained amounts of sickness in the aircraft. Not all of this will land in the blue-and-white sick bags. There is nothing worse than streams of vomit splashing up and down the floor of a buffeted C-130. The smell and colour provides further contagion. Military parachuting in large numbers cannot be described as anything like sports parachuting. It is a relief when they open the jump doors and the men once again get to taste fresh air.

Wind on the ground can be as problematic as wind in the air. The first action on landing is to get rid of one of the capewells – the metal risers on either shoulder – which helps to deflate the canopy. Failure to execute this manoeuvre leads to a wind-assisted drag along the ground at speed, with all the facial and bodily abrasions that follow.

Hard landings can lead to concussion. Once this occurs, the injured party is banned from parachuting for two weeks. On a major exercise, a number of simulated parachute assaults may take place within a couple of weeks. This occurred in February 1982 when 2 PARA were exercising in Thetford. Corporal Taff Evans was concussed in the first jump, and subsequently not allowed to parachute during the remaining exercise jumps. He was confined to the drop zone at Tottington Warren as ‘hired ground support help’ when an unfortunate paratrooper landed (and was stuck) in a tree. This is not recommended. Corporal Evans raced over to the entangled jumper and shouted to him to jettison his container. The container is the ‘wrapping’ for all the operational equipment, including the fighting order and weaponry that the men use on the ground. It is the life-blood: of their rations, ammunition, medical stores, clothing, sleeping bag and any ponchos for living in the field protected from the elements. The soldier duly dropped his container, which landed squarely on the head of Corporal Evans. The medics shook their heads in disbelief as they drove the once more unconscious corporal to the hospital for the second time. He never even had the opportunity to cry ‘MEDIC!’

Corporal Evans became the 28th casualty of the February 1982 jump. It was one of those jumps where the ground party hides the wind meter under their jackets to make the jump seem within legal limits – or at least that is what we used to tell ourselves on those jumps with large casualty numbers. These figures did not include Private McVey, who did not jump, as he had passed out from extreme air sickness in the Hercules aircraft after two hours of low-level buffeting over the North Sea.

Concussions and hard landings are all amplified if forced to conduct a back landing. In the menu of landings there are really only six alternatives: a forward left, a forward right, a side left, a side right, a back left and a back right. There is no such thing as an ‘ass over elbow straight forward’ or ‘straight back’, as each jumper is required to pull on the risers on one side in order to enable a landing in the best direction, which is determined by the wind. Pulling on the risers, which spills wind from the canopy above, is also the technique to steer away from other jumpers in the crowded airspace.

Jumps involving large streams of Hercules aircraft (affectionately known as Fat Alberts) used to occur regularly on ABEX’s (Airborne Exercises). In the 1980s and 1990s there would be nine stretched Hercules which could each drop over 90 troops, with a further six aircraft dropping platforms with heavier equipment such as trucks or light artillery pieces. A typical stream would drop 792 troops in one wave – as long as the DZ was big enough. I was the Chief of Staff of 5 Airborne Brigade when our Staff Officers Handbook, the bible on planning from that era, told me that we had over 60 Hercules in the fleet. With the attrition of the fleet since that time, and the air bridges to Iraq and Afghanistan of the last 10 years, we now only have around one-third of that total.

I was CO of 2 PARA when we assembled nine Hercules aircraft for a large battalion-sized jump back into southern England from an exercise in Scotland. The weather was perfect. It was a bright summer’s day with no wind and no cloud cover – ideal parachuting weather. What we did not bank on was the incompetence of the senior staff officer of 16 Air Assault Brigade. Under the latest round of defence cuts in late 1999, 5 Airborne Brigade was disbanded and merged with 24 Airmobile Brigade. The majority of the staff of 24 Airmobile Brigade stayed in place to form 16 Air Assault Brigade. Not many of the staff knew much about parachuting. As it turned out, not many of them even knew how to tell the time.

All operations around the world (and military exercises) are timed against Zulu time so there is a common baseline for all clocks. It was the summer and we were now on British Summer Time, which is Alpha time: one hour forward of Zulu time. The staff had never been taught the ‘spring forward, fall back’ approach to understanding where the clock should be at the correct time of the year.

We commenced our activity at P minus 40 minutes (P hour is parachuting hour) with checking our equipment, hooking up and getting ready for the jump. But when we approached the DZ we were told we would have to abort: there was live firing on the ground and we would run straight into it. We would be killed by rifle fire should we jump. Our jump window had closed one hour earlier. The staff had used the wrong clock. I was furious. To give the commander of 16 Air Assault Brigade his due, he subsequently came to my office to apologise. This was one of those rare occurrences – normally the protocol is the other way round – as he metaphorically ‘placed his feet in my in-tray’. His chief-of-staff who had made the cock-up never did progress very far in the army, but the apologetic commander was a gentleman and became the Chief of the General Staff and Head of the Army as General Sir Peter Wall. I would follow him to war anywhere and at any time (as long as he has staff who can convert the time zone clocks).

You can never have too much information on time zones. In the digital era, I had four clocks on my wall in Tampa, which read from left to right and top to bottom:

| 12:31 | 16:31 | 19:31 | 21:01 | |

| TAMPA | ZULU | QATAR | AFGHANISTAN |

Confusion of time zones leads to bizarre anomalies. They forgot to adjust the clocks incrementally on the voyage to the South Atlantic during the Falklands War, so there was a four-hour time jump on our watches in one go while in the same latitude and longitude, producing a sort of ‘jet lag by proxy’. Once we had landed in the Falklands, we got up at 11am according to our Zulu time watches (in reality it was 7am local time). We attacked Goose Green at 6am on our watches: 2am in the Falklands. Video conferences may take place at a leisurely 11.00am in London but it is 6am in the USA (the bane of my Monday mornings on my Tampa, USA tour).

Not one of these parachuting problems occurred at Brize Norton. With the jumps course completed and men awarded their wings, the soldiers and officers scurried away to sew their prized new possessions on their sweaters. It was remarkable how many sewed them on the left arm – the wrong arm. They were very much still ‘crows’: those with no experience and novices.

I now had my beret and my wings. I was about to lead the lions of 6 Platoon, B Company, 2 PARA who already had their berets and wings, and by the end of the Falklands campaign in June 1982, I might even class myself as one of that breed. I would then be a lion in a den of Daniels. I would absolutely know the real meaning behind Talleyrand’s saying that he feared one lion leading 100 sheep more than he feared one sheep leading 100 lions. I make no apologies for repeating that from the opening chapter.4a

3 All of these were written in my diary. Shaw’s quote is from Man and Superman. We wanted to be the latter.

4 Richard Hillary was also included as a subject in a chapter in Sebastian Faulks’ book The Fatal Englishman. The army equivalent of this is probably Memoirs of an Infantry Officer by Siegfried Sassoon. My naval colleagues have not come up with a satisfactory answer to their seminal work, although one told me that the seminal RAF book is probably The Brake Fluid Manager’s Handbook.

4a I am related by marriage to the famous comedian, the late Ronnie Barker. His sister is my Aunt Eileen who married my mother’s brother, Uncle Raymond. I think he would have rather liked my use of the English language in this section.