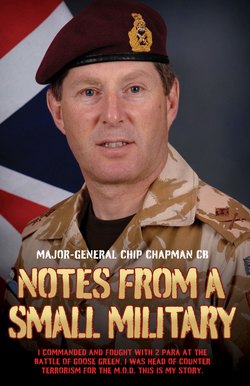

Читать книгу Notes From a Small Military - I Commanded and Fought with 2 Para at the Battle of Goose Green. I was Head of Counter Terrorism for the M.O.D. This is my True Story - Major-General Chip Chapman - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

LIONS LED BY DONKEYS

ОглавлениеI joined the army in 1980 on a three-year Short Service Commission and managed to extend it for 30 more years. It was an army 229,700-strong, including the Territorial Army (TA), and still full of historic names and nuances. The TA was more widely known among regular soldiers at the time as ‘Stupid TA Bastards’ or STABs. Now that the army is an Equal Opportunities Employer such language is no longer used: the TA now has an equal opportunity to be killed in Afghanistan alongside regular colleagues.

The TA reciprocated in their dislike of regular soldiers, who were known by them as ‘Arrogant Regular Army Bastards’ or ARABs. The Territorial Army is to change its name for the first time in more than 100 years to become the Army Reserve (AR) and we already have the first two letters of a new acronym for the regular army to use. Orwell was probably right that although all animals are equal, some are more equal than others; not that we were animals. The army’s two component parts, the Regular and the TA, each thought the others were bastards, and so collectively the army was made up a bunch of bastards – but an increasingly professional bunch of bastards.

We had Hussars and Lancers (including ‘vulgar fractions’ with regiments such as the 16/5th Lancers), and KINGS and QUEENS. A notice board in Gibraltar once told me to be warned as ‘4 QUEENS were exercising’ which seemed a more appropriate sign for a gay bar in the Vauxhall district of London, more particularly the famous Royal Vauxhall Tavern (or RVT), rather than as a military unit going about its tactical business.

Lest you think that there is anything untoward and prejudiced in my picture of the RVT, let me say that I lived in Vauxhall for three years. I walked to work, and on my way to the Ministry of Defence my route took me past the RVT, and then via either the Queen Ann Pub (reputedly the oldest strip joint in London), or the Headquarters of MI6 (or to give its official name, the Secret Intelligence Service). In my career, I only ever visited one of these three locations. It should be obvious which of these three it was, but let me say that both the RVT and the Queen Ann have security on a par with trying to get in to Sir Terry Farrell’s architecturally interesting Embankment Headquarters of the SIS. For the sake of both the Bond franchise and reasons of national security, I assume that MI6 have a refined business continuity plan, for the SIS Headquarters was blown to pieces in Skyfall.

It was a male and testosterone-dominated army, very different from the very professional inclusive army of today. There would have been no noted contradiction between the Soldier News front-page headline of 12 December 1980 that proclaimed ‘GIRLS TO GET GUNS’ following the announcement in the House of Commons by Francis Pym, the Secretary of State for Defence, with that newspaper’s ‘Soldier Bird’ colour photo portrait of a Miss Lyn McCarthy. Soldier Bird really was the title of the pin-up page. Although, as this was Christmas, the 1981 calendar included an added untitled double-spread bonus of another lady without pyjamas a few pages later. Miss McCarthy was currently appearing in Wot! No Pyjamas? at the Whitehall Theatre. I can confirm that she was not wearing any pyjamas. I do not believe you will see this theatrical tour de force from the artistic stable of the noted Soho impresario, Paul Raymond, revived any time soon. Nor did we know much about the role of women in the army. One exam howler on this subject included the statement: ‘Women were used extensively during the Second World War; some were even shipped over to France.’

I came from a family with little military background. There were no famous generals or soldiers in our lineage. If I had featured in the TV series Who Do You Think You Are? the bland answer of generations of Cornish agricultural labourers would not have been too far from the truth – and that was the successful side of the family.

Like most British families, we had suffered from death in the First World War: a great-uncle had been killed at the Battle of Loos as a young private in the 8th (Service) Battalion of the Devons, but that was about the limit of the family military prowess. Great-Uncle Albert Stone was one of the 1,105,5531 British military casualties in the 20th century, when a military death occurred at an average of one every 48 minutes.

The Second World War passed us by, bar the death of my grandmother who was killed in a Luftwaffe raid on Plymouth during the night of 22/23 April 1941 as she harboured in a communal air raid shelter that took a direct hit: the worst single civilian tragedy of the war in Plymouth. She was also a part of an increasing trend in the 20th century and beyond – that the brutality of war now reached civilians in a way that it had not in previous centuries. More civilians would die with each war (particularly in non-state conflicts such as civil wars) and the consequences of war would touch far more people, and in a wider arc, as the century unfolded. My father was an orphan at the age of five.

The catalyst for my application to join the army had been no more profound than watching the BBC current affairs programme Panorama about Sandhurst. I thought all the assault courses and running around looked like quite good fun: I could do that. Going to Sandhurst might at least solidify my future apolitical leanings. At university, one flirted with everything. I even flirted with anarchy: I attended an anarchist meeting. The assembled anarchists waited outside a locked room. They could not gain entry. The hall porter came along and inquired as to who was in charge.

‘No one, we’re anarchists,’ came the reply.

‘Well, someone has to say they are in charge and sign the book,’ the hall porter grumpily replied.

Suitably miffed, and in contravention of the universal principles of anarchy, an individual fulfilled the leadership burden and duly signed. For the next two hours, our nascent anarchists discussed how to arrange the chairs in a non-hierarchical fashion. My flirtation with anarchy was over. Not that this was serious. Student politics were absurd. At a student University General Meeting, the International Socialists proposed a motion to send a coach to attend an annual protest march against Bloody Sunday in Northern Ireland. I put an amendment to their motion to quash it. Thankfully for us all, the entire apathy of the student body meant that all came to naught, for the meeting was not quorate.

My Sandhurst training course was entitled Post-University Course Number 9, shortened to POSUC 9. This was accommodated in and run out of Victory College. Every officer cadet in the college was a university graduate and all were deemed to be already semi-competent, due to their service at a University Officer Training Corps (Liverpool OTC in my case). We were only to complete 17 weeks training at Sandhurst before we graduated. Our former OTC service meant that we were seemingly competent in the art of being able to dress ourselves and to strip and assemble a self-loading rifle (SLR). On completing the course I won a prize of sorts, being presented with the ‘Show Clean’ book by Colour Sergeant Scott of the Welsh Guards. If there was any dirt or crease out of line, this was recorded in the book every morning. It was this book that was paraded at 2200 hours, the misdemeanour was read out and it was checked whether the error had been corrected. My copy of the book was inscribed that it had been given to me for my inability to ‘appear neat, clean and tidy in any form of dress whatsoever’. A ‘show clean’ would be determined at the morning ritual of being inspected and being found wanting. In particular I could not bull (army parlance for polish vigorously) shoes to the correct standard of shininess. I still cannot. I still have those shoes, and they are still not very clean. Fluff was particularly offensive. Our mission at Sandhurst was not to destroy the enemy or hold a particular piece of ground: it was to rid the world of its offensive fluff.

We bounced off the walls with multiple ‘changing parades’. There was a different form of dress for different lessons at different parts of the day. The horror of being incorrectly dressed, or not having pristine clothing, worried more than the most junior. On 6 February 2011 – during my time as Senior British Military Advisor, HQ United States Central Command, Tampa – I was watching an evening screening at an American cinema of The King’s Speech in which Colin Firth gives his fine Oscar-winning representation of George VI. The audience seemed a curious assortment. The cinema was full of only two types of people – women and gay couples. I was the only heterosexual male member of the audience. I now know this to be because it was the same evening as Super Bowl XLV. This event, won in 2011 by the Green Bay Packers, attracts the largest television viewing figure of the American calendar. I can safely tell you which demographic is not watching the Super Bowl, if that would be of help to future advertising agencies.

The King’s Speech led to a number of requests to the British team working in Florida, via the British Consulate in Miami, for information on what the medal ribbons worn by George VI represented. Ever willing to do our bit for British foreign policy, the team duly complied. One of our young naval officers knew an academic at the Britannia Royal Naval College at Dartmouth who was an expert on the subject. In fact, the naval uniform of King George VI was kept on display in a glass cabinet at the college. This was a saving grace on the occasion that Field Marshal the Viscount Montgomery of Alamein KG (Knight of the Garter – the senior chivalric order of the UK) came to take a pass-off parade at Britannia. One detail was missing. His uniform was without the star of the Knight of the Garter. The professional head of the Armed Forces – the Chief of the Imperial General Staff – was incorrectly dressed. Or he would have been if his aides had not broken in to the cabinet containing the naval uniform of George VI, unpicked the Order of the Garter and quickly attached it to Monty’s jacket. He was now once again a KG. In former days, being incorrectly dressed would have been a treasonable offence.

Monty would have recognised elements of our dress from his own service in the trenches. This was the late 20th century, yet we still wore puttees around our ankles: pieces of flannelette cloth that would have been familiar to those who fought in the Boer War. These neatly complemented our Directly Moulded Sole (DMS) short combat boots, which were comfortable but made of compressed cardboard. These had only been introduced in 1958 so were a comparatively new addition to our fighting prowess. The compressed cardboard construction had an obvious flaw: when it rained they soaked up water like a sponge. A Daily Express Magazine article a couple of years later on ‘the boot that nearly lost us the Falklands War’ was not wholly inaccurate. Every other army in the world was wearing combat high boots.

My brief sojourn at Sandhurst was not the shortest course available. That was reserved for professional officers (a curious paradigm in that it might have contrasted with the notion that the remainder of us were unprofessional officers). Professional officers were those who had already completed training for a profession before joining the army. There were men of the cloth, doctors, nurses, lawyers and veterinary surgeons: they only did four weeks training. This really was only enough time to get to grips with the correct end of a rifle barrel and the right way to put on their pieces of flannelette. This course was fondly known as the ‘Vicars and Tarts’ course.

In the days of the Cold War, we often mused why doctors joined the army when they would be dealing only with blisters and venereal disease. As my career progressed, army doctors would indeed earn their pay dealing with the trauma of the battlefields they would subsequently confront with alarming regularity. But that was to be in the future. In the interim, it remained their lot to dole out condoms when a battalion exercised overseas. They were always conveniently positioned at the Guard Room as the soldiers exited an overseas camp to sample the local delights.

Soldiers have always been up for some ‘horizontal refreshment’. Field Marshal Montgomery (when a mere major general) nearly ended his career prematurely with an edict that condoms – and recognised brothels – should be used to prevent VD during the Phoney War with Germany of 1939. The complaints from the assembled chaplains of Monty’s so-called obscene language went right to the top of the army and Viscount Alanbrooke (who we will meet later) came to his rescue. Monty later reflected that his written order had caused VD to cease, although given the strictures of medical-in-confidence abided to by the medical fraternity I reckon Montgomery was in boastful territory on that one. Monty returned to the VD charge later in the war, chastising the New Zealander, General Freyberg (a VC winner from the First World War) about the health of the Second New Zealand Expeditionary Force. Freyberg is reputed to have replied, ‘If they can’t f***, they can’t fight.’ Not much has changed.

I leave the army as it seeks to implement ‘Army 2020’. This does not mean that the army will be left with only 2,020 soldiers. There are still seven years left to bring the figure down to 82,000 regulars and increase (if they find the funding) the TA to 30,000. The army has been reducing in size ever since the Korean War in 1952. At least the modern soldier no longer wears puttees.

The height of my incompetence at Sandhurst came on the one day when I was actually well turned out with good shoes, and no fluff. But the system was not to be outdone – this was not enough: it was raining and 8 o’clock in the morning. I was told to present myself at the 10pm ‘show clean’ parade and ‘show good weather’. Thankfully, I did not have to show sunny weather, as a raw December evening would have presented me with insurmountable problems.

Show clean parades were always preceded in the early evening by cleaning parades. This communal activity occurred for about two hours when the officer cadets collectively bulled their shoes, or buffed their Sam Browne leather belts. It meant there was no time for studying tactics manuals – a slight flaw when, within a year, I would be off to fight in the Falklands campaign. Sandhurst, as the instructors will tell you, is not an academy for tactics – it uses infantry tactics as a basis to teach or refine leadership.

Upon graduating from Sandhurst, young officers would go to their arm or branch of service, such as the artillery or infantry, for their special-to-arm training. For the infantry, this is the Platoon Commanders Battle Course (PCBC). I did rather well on that course, as did six of the seven Parachute Regiment officers who attended with me, as by 1983 – having already completed three years of service – the six had already fought a war. In the 1980s and 1990s, officers on Short Service Commissions did not do their special-to-arm training until they were shown to be serious about the army, and had an intention to convert to a longer commission. Only full-career officers were deemed to have a need to be competent. The army has now changed this. Due to duty of care considerations, it is deemed imprudent for you to be killed when you don’t know what you are doing.

We caught up and recovered from our perpetual tiredness by sleeping through the central lectures on battles, warfare and the history of warfare that were held in the Churchill Hall. There are very few officer cadets in the history of the Sandhurst Academy with a complete set of notes from any given military history lecture. This was a shame, as I might have learnt at an early age about those things that perplex later in one’s career. For instance, that concepts such as fear, honour and interest as related to us by Thucydides (in his classic book on the Peloponnesian War that should be required reading for all future military students) remain as relevant today as they were in the ancient world when seeking to understand why wars are fought. And that ‘tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat’, according to the ancient Chinese military general, Sun Tzu. All that would have to wait. The current instructors at Sandhurst, who sit in on lectures at the Churchill Hall, inform me that to overcome the problem of fatigue and prevent sleeping among officer cadets, a simple solution has been devised. The heating is turned down or off: the shivering assembled students can do no other than stay awake.

I was to join the Parachute Regiment. I had already been selected while at university. Each regiment of the British army looks for differing qualities in its officers. The Parachute Regiment, a regiment that believes its place to be in the ‘van of battle’, looks for a warrior leader (or at least I did when I went back to sit on boards to select officer cadets of the required quality), with intellect, who can triumph in adversity. A cavalry colleague of mine once told me that having sat on various selection boards, he believed that he had now got his system down to a fine art and actually only needed to ask one succinct question: ‘With whom does your mother hunt?’

Each regiment has its own flavour and particular social and cultural register given the subtle differences to which I have alluded. One is not better than the other – they are merely different. I know this to be true, for I had the temerity as a staff college student to do my research paper on ‘The Social and Educational Origins of the British Officer Corps in the Age of Meritocracy’, and to have my paper marked by a furious Guards lieutenant colonel. My top tip for youngsters wanting to join as an officer is: if you want to be a general do not join the Pioneer Corps. If you do want to be a general, joining the infantry, cavalry, artillery or engineers improves your prospects immeasurably.

The most meritocratic organisation in the British army is the Parachute Regiment. This is a proven fact. My own studies showed that 50 per cent of Parachute Regiment officers were from public schools and 50 per cent from grammar/comprehensive schools. We have everything from Old Etonians (one of the four officer cadets joining the regiment in my intake was indeed from ‘Slough Grammar’, the sobriquet for the toffs’ school) to those who went to (the generic) ‘Workington Comprehensive’. There was no hidden agenda in my interest in this subject; for me, it was a follow-on from a ‘War and Society’ course I had completed at Lancaster University (and where I first theoretically met the Prussian military theorist, Clausewitz) under the wonderful Professor John Gooch. This was back in the days when, in the university student lavatories, there would invariably be graffiti above a toilet roll holder of hard wax paper that told us: ‘Sociology degree – please take one’. With the passage of time, and changes in society (very close to what ‘War and Society’ was about – we no longer purchase our commissions), I gather that the modern equivalent is ‘Media Studies Degree: please take one’. Does anyone do sociology these days?

Napoleon once said, ‘Space I can recover, time, never’. So it was for us at Sandhurst. My space was in Room 101 (George Orwell would have been proud), a tiny enclave where dust was the enemy of the righteous and bad hospital corners on blanket ends incurred the wrath of the colour sergeant. To conserve time, and never having perfected the art of hospital corners (a fact to which my wife can testify), I spent too many nights sleeping on the floor in an army issue sleeping bag. I am glad to say that we have now progressed to the point where the duvet is now an acceptable sleeping accessory and that the modern generations of officer cadets do not know how lucky they are. Duvets are a real sign of progress. A wizened old Parachute Regiment quartermaster, Norman Menzies (inevitably nicknamed ‘Norman the Store Man’), who had joined the army in the late 1950s, once bemoaned to me that the army had gone soft when they started issuing sleeping bags in the 1960s instead of two blankets as part of the marching order equipment for exercises or operations.

Despite my incompetence, I graduated well. This had as much to do with the fact that I was very fit and very sporty. Being in the football First XI and one of the Academy’s star boxers was always a bonus. You even got to miss some exercises (a double bonus, as there were no show cleans on the hills of Scotland or on the rainy/snowy hills of Brecon). I even got to miss some of the drill parades in the mornings, as I would damage my nose (or rather my opponent would – I was no malingerer) in just about every bout and needed to report sick the morning after my pugilism to be patched up. I think they called this ‘duty of care’.

I left Sandhurst consciously incompetent. Fortunately – for the army and defence – I managed to move further to the right on the scale of competence with time and each succeeding job. With our postings system we change jobs roughly every two years, and the cycle begins again – subconsciously incompetent leading to consciously incompetent status and onwards to a state of being consciously competent and then the real nirvana of subconscious competency.

I had the illusion that I was competent when I received my first appraisal report. It told me that I was ‘GOOD’. I was rather pleased that I was good. I did not realise, due to inexperience, that this was code for CRAP. Above GOOD stood VERY GOOD and above VERY GOOD was EXCELLENT. This led to the pinnacle, which was OUTSTANDING. I was initially a D-grade officer.

During my RMA Sandhurst course, Ronald Reagan was elected US President, which I marked with a ‘permission to break out the live rounds’ radio message to higher HQ on a wet November night on Salisbury Plain. This message was a marvel – it showed I had managed to tune the impossibly difficult A41 Larkspur radio and that the batteries worked. The A41 battery resembled four house bricks in size and weight. Radios and batteries are the bane of all those in the infantry. If anyone out there can invent a battery that does not weigh far too much and that holds its power long enough not to require so many house bricks, I promise to buy them their choice of ale. Volunteering to carry five days’ worth of batteries on an airborne exercise was never the choice of a sane man.

Fortunately, we were issued with the new Clansman radio system in time for the Falklands War. This worked perfectly, and we were now down to two house bricks. The technological advancement of the last decade means the army now has the Bowman radio system. In its initial trials, its initials were deemed to stand for ‘Better Off with Map and Nokia’, thus proving that technology never delivers what it says and on time. Field Marshal Rommel once said that his most important weapon system was a radio; he never mentioned the batteries.

Weight is the bane of the infantry. Those who crossed no man’s land at the Somme in 1916 were carrying 90 pounds on their backs. Now we have equipment such as Osprey – the ballistic protection system (or body armour for those who like their language brief and simple) and one of the most inaptly named pieces of army equipment. An osprey is fast and agile, seizes its prey in an instant and carries the fish away (the fish is caught and carried so that it is forward facing, both for aerodynamic reasons and so it gets a good view of the world on its final fatal journey). The modern infantry is anything but agile, fast, and aerodynamic. The Osprey body armour weighs 22 pounds.

I thought I had put my description of the curse of weight to bed in my musings when I came upon an article in the August 2011 edition of Jane’s International Defence Review2 This is what it said, with my reflections in square brackets:

Burden reduction has been an abiding theme of DCC [Dismounted Close Combat. I preferred the more descriptive former title: FIST (Future Infantry Soldier Technology). But we always made a ham fist of bringing any equipment in which actually reduced the burden] systems since 2008 and will remain so. To date the maximum weight carried by the individual infantryman has been driven down by 9kg to 66kg. [That’s 145 pounds in imperial weight2a] through battery and power management improvements, adoption of lighter radios, polymer magazines, lighter equipment, water scavenging, and ‘other measures’. [So why is it still more weight than the first day of the Somme?] The aim is to reduce the maximum to 60kg by the end of Epoch 1 of the DCC capability management plan (which runs from 2010 – 15) to 40kg by the end of Epoch 2 (2016 – 20) and to 30kg by the end of Epoch 3 (2021 – 35).

This is a classic example of how defence ‘mystifies and misleads’ (a phrase first used about the Confederate general, Stonewall Jackson – acknowledged as one of the few geniuses of the American Civil War). The reader will be quite content with the familiarity of a number of years bracketed together and quite baffled (as am I) by what on earth the meaning of an epoch is that so sets it apart from the years.

Apparently, the insights I have let you into in the preceding section came from Major General Colin White. Now, I have come across Colin White and he is a very sound and competent officer. I remember him mostly for the fact that he had the most outstanding eyebrows of anyone I have met in the British army. You could land a helicopter on them: they protrude like a landing pad, and with such length. They are a marvel of eyebrow technology.

Major General White worked in the Defence Equipment and Support area (DE&S) when he shared his insights at a conference into the weight-carrying burden of the infantry. Given that we are still asked to carry more than the average mule, you might think that Major General White is one of those senior officers who must be a Gilbert and Sullivan caricature: the real life model of a modern major general. He is not. I am being careful here in not equating mules and donkeys in case you think I am one of those ‘lions’ (our soldiers) ‘led by donkeys’ (our officers). I am more in favour of Talleyrand’s suggestion (from the French Revolution) that he feared one lion leading 100 sheep more than he feared one sheep leading 100 lions. I would like to think that my career has shown a lion leading a pride of lions – an apt description of the pure leadership joy of working with motivated men – which is always the most efficacious outcome.

Major General White’s eyebrows and their proximity to helicopter landing pads and his employment in equipment procurement lead me to think of disastrous stories in this field. Helicopters (unlike General White’s eyebrows) are fragile machines. God created birds to fly. He did not intend helicopters to invade the space of birds, and that is why the testing of helicopters before they enter service includes their potential to cope with bird strikes. One test apparently involves launching dead chickens from a machine to simulate a bird flying into the windscreen of a helicopter. To show that this is a contemporaneous story, the helicopter in this case was the Merlin – the newest in the aviation inventory of the armed forces. What was not supposed to be in the test was the launching of a frozen chicken. It will not surprise you to learn that not only did the chicken penetrate the windscreen, but it also passed completely through the helicopter and exited after having punched its way through the disintegrating tail rotor. I hope I am never in a helicopter that runs in to a frozen chicken while in flight, for there is a sage lesson here that has nothing to do with the recipe for stuffing.

You would never expect two frozen chicken stories in a career, but another appeared during my sojourn in Tampa. This one was even more bizarre. During the Arab Spring of 2011 – 2012, a Yemeni garrison was beleaguered in a town called Zinjibar near the historic former Royal Naval coaling station of Aden. Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) was poised to overrun the garrison. The Americans used global positioning system (GPS)-guided parachutes to drop a number of days of resupply to the garrison in the expectation that a relieving local force from Aden would attack to produce a link-up with Zinjibar. Unfortunately, the relieving brigade sat on its haunches. The Americans became exasperated and after a number of days of Yemeni inactivity decided they would not waste their time resupplying the garrison for a second time. So it was left to a neighbouring friendly country’s air force, who were slightly more concerned with the situation than were the Americans, but with less technological know-how and capability to drop (among other commodities) 6,000 pounds of frozen chickens – along with sweet edible dates, because it was Ramadan – and other essentials such as bullets, fuel and water to help relieve the garrison.

Those not acquainted with military matters may have visions of frozen chickens with individual parachutes drifting towards terra firma. I can put your mind, and imagination, to rest on this account: these were palletised. Most of the chickens landed in the hands of the enemy from a spectacular miss-drop, well away from the intended objective.

I came across equipment woes early in my service. A certain Private Arpino of B Company 2 PARA in the Falklands War thought he was carrying the excellent Carl Gustav 84mm Anti-Tank weapon system. This was known more popularly as the ‘Charlie Gee’, except that the Charlie Gee was not popular, being apparently invented with the specific purpose of being the most difficult man-portable (a very loose use of that term) weapon system ever invented. It had a spongy and slightly elasticised carrying strap that made 33-plus pounds of metal bounce incessantly. It was the least-favoured weapon to be forced to carry on a company run and had to be rotated frequently to preclude it being tossed into the Aldershot Canal in times of peace. But we were now at war, and the Charlie Gee might come in useful against the limited number of Argentinian armoured vehicles scattered around the Falklands.

Arpino carried the Charlie Gee throughout the entire conflict. He had not had the chance to fire it in anger until an opportunity presented itself at the Battle of Wireless Ridge. The sun broke after the night attack, and so had the enemy. Their will to fight had collapsed. From the ridgeline, one could see Argentinian soldiers fleeing the hills surrounding Port Stanley. It was just about the end of the Falklands War. And there in the valley at Moody Brook lay a lone and docile abandoned helicopter. Arpino gave a pleading puppy dog look to the company commander, who needed to do no more than slightly acknowledge and nod his head to signify that Arpino deserved his moment to finally use his weapon system. The Charlie Gee required a loader for its rounds. Here is what happened.

Arpino: ‘Load.’

The Loader: ‘Load’ (repeated by the loader to indicate he had understood and would comply with the instruction from the firer) followed by ‘Loaded’ when the system was ‘bombed up’.

Arpino: ‘Firing now’… Click… Pause… ‘Misfire’… Click again. ‘Misfire, unload.’

The drill was repeated and repeated with nothing happening. The firing pin was replaced… and still nothing happened. Arpino had been carrying a lump of useless metal rather than a functioning weapon system.

But we rarely broke out the live rounds during the era of Reagan and Margaret Thatcher in the way that the USA and UK did in the subsequent decades that followed from the 1990s onwards. Well, the UK might have broken out the live ammunition in the Falklands in 1982, and the Americans in Nicaragua and Grenada in 1983, but these were sideshows in the stable era of the Cold War.

But sideshows can have a dramatic influence on individual lives. It is when ordinary men can do extraordinary things – and some pay with their lives. One of those who died in the Falklands was Corporal Steve Prior. Twenty-eight years later I was asked to attend a 2 PARA Goose Green lunch at Colchester. The guest of honour was a frail Margaret (Baroness) Thatcher. One of the men serving in 2 PARA was the nephew of Steve Prior. He asked to meet me. He was subsequently killed in action in Afghanistan in 2011 at the same age, 27, as his uncle. His wife had given birth only some weeks before.

I had the privilege – and I use that word advisedly – to attend the funeral of Corporal Mark Wright in 2006. It does not matter if the following story is not 100 per cent accurate, for as the famous line in John Ford’s film The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance tells us, ‘When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.’ In military circles that is amplified more than most – think Melville and Coghill saving the Colours at Isandlwana in 1879 prior to the defence of Rorke’s Drift, best known from the film Zulu. We do not know what really happened, but for their troubles, and following a tireless campaign by Mrs Coghill, both were – perhaps slightly extraordinarily – awarded the Victoria Cross 29 years after they were killed.

The Mark Wright story goes something as follows. Corporal Mark Wright had joined the army because he was in awe of his uncle Andy, who was originally in 3 Para. Wright was a Mortar Fire Controller (MFC) on a hillside in Afghanistan when a number of his fellow paratroopers were caught and wounded in a Soviet era minefield. When the personnel were ‘hit’, Mark Wright left his position and prodded in to rescue the first man. He then rescued the second. He was rescuing the third when, the story goes, a Chinook helicopter hovered above and the downdraft set off a number of ‘sympathetic’ explosions (a totally inappropriate but technical phrase in the military). Mark Wright was badly wounded. The paratrooper he was rescuing at the time (who had lost a leg) said, ‘You’re going to be OK; you’re going to be OK.’

‘I’m not,’ Wright replied. ‘It’s 45 degrees out here and I’m f***ing freezing, I’m dying, but before I die I want you to pass on two messages. First, tell my fiancée Gillian that I love her, and secondly, tell my Uncle Alex that I died a professional soldier.’

It is men like this that I had the privilege to serve with – the good and the bad, but all committed to each other, with an innate sense of ‘mate-hood’. Sergeant Barry Norman of 2 PARA (Lieutenant Colonel H Jones’ bodyguard in the Falklands) summed this up a few years after the Falklands War when he said of the men in that conflict: ‘It was the blokes… It was the section commanders and Toms who went forward and took the enemy positions. They didn’t do it for the government; they didn’t do it for the Falkland Islanders; they didn’t even do it for Maggie Thatcher. They did it for each other.’

The first battle honour for the Parachute Regiment was the Bruneval Raid in France in February 1942. At a time when Britain was on the strategic, operational, and tactical defensive, Churchill demanded an active raiding policy designed to keep the spirit of the offence alive. In February 1982, 2 PARA celebrated the 40th anniversary of that battle with the living veterans. The CO of 2 PARA at the time, H Jones, gave the after-dinner speech pleading that if we, the modern 2 PARA, were ever committed to battle, then he hoped that we could live up to the deeds of those who had come before. He could not have predicted that only four months later, on 28 May 1982, he would be leading a charge at Goose Green that would lead to his own death. Nevertheless, the spirit lived on. He was not merely the CO, he was the custodian of all those great officers and paratroopers who had come before. For the Parachute Regiment, the spirit of our early defining Battle of Arnhem lived and still lives on. In General Eisenhower’s letter to the defeated General Urquhart of 1st Airborne Division, dated 8 October 1944, Ike said, ‘Your officers and men were magnificent. Pressed from every side, without relief, reinforcement or respite, they inflicted such losses on the Nazis that his infantry dared not close with them. In an unremitting hail of steel from German snipers, machine guns, mortars, rockets, cannon of all calibres and self-propelled and tank artillery, they never flinched, never wavered. They held steadfastly.’

The British army is still like that. About 25 years ago we rediscovered the military philosopher, Clausewitz. What that great Prussian said some two centuries ago is still applicable today, as the British army continues to campaign in trying circumstances, sometimes akin to Arnhem in its current fights in Afghanistan. The steadfastness that Clausewitz spoke of resonates wider. It is summed up in his words, and is as applicable to individuals, units and the wider army. It is this: ‘An army that maintains its cohesion under the most murderous fire; that cannot be shaken by imaginary fears and resists well-found ones with all its might; whose physical power like the muscles of an athlete, have been steeled by training in privation and effort; that is mindful of all these duties and qualities by virtue of the single powerful idea of the honour of its arms – such an army is imbued with the true military spirit.’

We still have such an army: whether we will for much longer might lead you to the final chapter. My Sandhurst course was not to equip me with the above qualities – but the Parachute Regiment eventually, and by chance or design, would.

1 From ‘A Century of Change: Trends in UK Statistics Since 1900’, House of Commons research paper 99/11, dated 21 December 1999.

2 Jane’s International Defence Review, Volume 44, August 2011, page 6: ‘UK Seeks Coherence for Dismounted Close Combat’.

2a Equivalent to the weight of a light welterweight boxer for the WBO, super lightweight for the WBA and junior welterweight for the IBF and WBO. Boxing is more confusing than the army. I use light welterweight as it is the weight I boxed at every time an opponent broke my nose. No one has ever gone in to combat carrying a boxer on his back but we continue to want our infantrymen to do so.