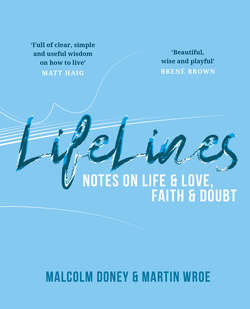

Читать книгу LifeLines - Malcolm Doney - Страница 28

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление19

Seize the day

Some days you wake up and it feels like morning hasn’t come. And that it won’t. You reach for the alarm and turn it off and now the alarm’s inside you. Warning you this will be a dark day. And then that thing which is not light dawns on you.

She’s gone.

He’s not going to make it.

It’s over.

Perhaps it’s less personal, more political. It really happened. Change was going to come, and it came, and it was not a good change.

The sense of dread rises. Queasiness. The pit in your stomach as your fears become physical.

Notice these emotions, don’t deny them, says the Persian poet Rumi:1 ‘Even if they’re a crowd of sorrows who violently sweep your house empty of its furniture.’

These sorrows don’t have to be buried. Bleak is how some days look, and we don’t have to know how to react. We might have to sit in this gloom for a while. Perhaps time will help our sight adjust.

‘Dear Americans,’ wrote Canadian novelist Margaret Atwood, the day after the 2016 US presidential election: ‘It will be all right in the long run. (How long? We will see.) You’ve been through worse, remember.’2

‘History takes such a long, long time,’ as the songwriter Bruce Cockburn, 3 sang. It was our mistake to think we could dictate its arrival time. No one knew this better than Civil Rights activist Martin Luther King, even on the darkest days. ‘The arc of the moral universe is long,’ he insisted, ‘but it bends towards justice.’4

Hope is not a synonym for optimism. Optimism is generated by the available evidence. But hope, says Professor Cornel West, will dare to defy the evidence. Hope says we can ‘go beyond the evidence to create new possibilities... to allow people to engage in heroic actions always against the odds, no guarantee whatsoever’.5

No guarantee, but our agnosticism about the future provides what essayist Rebecca Solnit calls a ‘spaciousness of uncertainty’. ‘Hope,’ she says ‘is a sense of the grand mystery of it all, the knowledge that we don’t know how it will turn out, that anything is possible.’6

The waiting is our chance to decide how we’d like things to be. ‘Hope imagines the future,’ says theologian Walter Wink. ‘And then acts as if that future is irresistible.’7 People of faith may draw on the conviction that good is at work in history, the hope the ancient psalmist had when she could say: ‘Even though I walk through the darkest valley, I will fear no evil, for you are with me; your rod and your staff, they comfort me.’8

For others, hope may rest in a sense that, for all the wrong turns, history’s general direction of travel is promising. The novelist E. B. White put this beautifully in a letter to a reader who harboured doubts about the future of humanity. Human society, wrote White, reminded him of how sailors talk of the weather as ‘a great bluffer’: ‘Things can look dark, then a break shows in the clouds, and all is changed, sometimes rather suddenly... Hang on to your hat. Hang on to your hope. And wind the clock, for tomorrow is another day.’9

The break in the clouds may come to us as friend, or stranger. As unexpected event. Even unwelcome. J. R. R. Tolkien, who had seen darker days than most in the trenches of the First World War, refused to give up on hope. Perhaps this was at the back of his mind when he wrote a scene in The Lord of the Rings, as war approached in Middle Earth:

‘“I wish it need not have happened in my time,” said Frodo.

“So do I,” said Gandalf, “And so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to us.”’10