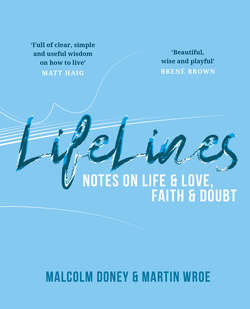

Читать книгу LifeLines - Malcolm Doney - Страница 32

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление23

TELL IT LIKE IT IS

Most of us are happy giving organisations and institutions a piece of our mind. It’s a vital part of our liberty to call such monoliths and their ethos to account. As writer Salman Rushdie says: ‘The moment you say that any idea system is sacred, whether it’s a religious belief system or a secular ideology, the moment you declare a set of ideas to be immune from criticism, satire, derision, or contempt, freedom of thought becomes impossible.’1

But what about when it gets personal? What do we do when someone we know needs to be brought to book? How honest are we prepared to be?

‘Criticism may not be agreeable, but it is necessary,’ said Winston Churchill. ‘It fulfils the same function as pain in the human body; it calls attention to the development of an unhealthy state of things.’2 Constructive criticism – from a coach, a mentor or a tutor – is essential for anyone who wants to improve their performance, in whatever field. And we’re sometimes too close to see what we’re doing wrong, or how to correct it.

If someone’s actions are in danger of ruining their own lives, or hurting other people, then we have a duty to intervene. It’s the shadow side of kindness. Another world leader from another century, Abraham Lincoln, said: ‘He has a right to criticise, who has a heart to help.’ But it’s then a question of how, and when.

The playwright Alan Bennett once said that there’s only one appropriate response on an opening night, and that’s: ‘Marvelous, marvellous, marvellous!’3 Anything else appears niggardly, cruel and discouraging to someone who’s at their most vulnerable. But what about that creaky bit in the second act? To be fair, Bennett isn’t saying that we ignore defects, it’s a matter of waiting until the excitement and paranoia has died down.

When one of Lincoln’s generals, say, screwed up, he would write him an enraged letter pointing out his deficiencies in excoriating detail. He called these his ‘hot’ letters. But they would remain unposted. He would put them in an envelope, marked, ‘never sent, never signed’. He waited for his rage to cool before delivering a more measured critique.

We live in the age of the ‘hot’ email, when we unload our vitriol on unsuspecting victims. This purging may be of some temporary use to us but not to anyone else. If we want to help someone else effect change, then we need to couch honest criticism in a positive framework.

In management speak, there’s a (much-derided) feedback technique known as the ‘shit sandwich’. You start by telling your colleague how well they’re generally doing, before forensically pulling apart their performance. You then end by saying how much better it’s going to be from now on. Critics of this critique have a point. It’s a formula which doesn’t recognise that individuals respond to criticism – and how it’s delivered – very differently. Some will only hear the good news; some will only hear the bad.

We have to gauge our honesty, and our criticism, to each circumstance and individual. But the shit still needs some kind of positive, helpful sandwich, otherwise it’s simply belittling. The only point of honest criticism is to help us get better. That’s why we need critical friends. As the tender, ancient psalmist pleaded: ‘Smite me in kindness.’