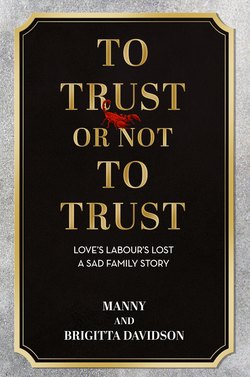

Читать книгу To Trust or Not To Trust - Love's Labours Lost. A Sad Family Story - Manny & Brigitta Davidson - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Manny’s Story, 1931–58

ОглавлениеThe story that follows is a story of families and of homes. It starts in 1901, when a thirteen-year-old Jewish boy set sail from the coast of what is now Latvia. He was leaving his family and his home. His name was Joseph Davidovics. His destination: South Africa.

In one sense, Joseph was alone. He was travelling without his parents, his brothers or his sisters. But he was not the only young Jewish person to be fleeing Latvia at the turn of the century. Anti-Semitism was commonplace. Terrible pogroms were to come. In 1901, that corner of the Russian Empire was not a promising place for a young Latvian Jewish boy with plans of improving himself.

The ship that carried Joseph to South Africa travelled via Liverpool. Here, he was obliged to show his passport to a British immigration officer.

‘Name?’ the immigration officer asked him.

‘Joseph Davidovics,’ Joseph replied.

‘Huh?’

‘Joseph Davidovics.’

‘Not any more,’ the immigration officer told him. ‘From now on, you’re Joseph Davidson.’

It was not uncommon in those days for Jewish people to anglicise their names. Joseph was my father, and the family name he passed on was decided upon by the whim of that Liverpudlian immigration official. We have remained Davidsons ever since.

Despite his unusual childhood, my father was a highly educated man, though I know very little about his education. He had exquisite copperplate handwriting and an incredibly wide and versatile vocabulary. He was erudite, articulate and spoke three or four languages. On his arrival in South Africa, he set about making enough money to bring his siblings over from Latvia. He had two brothers and two sisters, and all but one made the trip to the new continent that my father now called home. Reunited, they opened up what they called a ‘bazaar’, selling goods to the locals. It must have thrived, because over the next couple of decades the family set up a few of them. The entrepreneurial spirit was clearly strong in our family in spite of my father’s left-wing views, which were shaped, of course, by his background.

It was in South Africa that Joseph met my mother. Her name was Annie Sarah Gelb and she too came from a large family. Families were bigger in those days! Joseph and Annie married, and Annie took Joseph’s new, anglicised name. I would later name my property company ASDA Securities. ASDA stood for Annie Sarah Davidson. My mother was a very hardworking woman, supportive of my father, my sisters and myself. ASDA is a very sentimental name for me, and that made the events that were to follow just that little bit harder to bear. My parents had two daughters – Zelda and Barbara – and they moved to London in 1928. Mainly because they disliked the political situation in South Africa, but also to make the purchases that he sent to South Africa. The discrimination against black people was something that he was uncomfortable with. I was born in London in 1931. I was eight years old when Germany invaded Poland. On the first day of World War II, labelled as if I were a piece of luggage, I found myself being evacuated from supposedly dangerous Willesden to the safe haven of Northampton in the East Midlands. My memory of that time is very sketchy. I do not remember whether I was one of the cheerful mass of children whom the history books tell us sang their way to the station, or if my mother was one of the tearful mums weeping at the platform. But I do remember arriving in my new home town of Northampton, where there were whole streets of foster parents waiting to take in these sudden evacuees. Neither I nor my sisters had any idea whom we would be fostered with. Children were allocated on arrival: we were simply walked down the street and were told which house and family was to be ours.

Barbara and I were fostered by an elderly couple called Mr and Mrs Ballos. Our sister Zelda was next door. And although there would later be many horror stories about the indignities young people endured by less-than-sympathetic foster parents, my memories of my time in Northampton are happy ones. The Ballos family were kind to me. In fact, the worst memory I have of that time is of sitting on the ledge of a sweet shop in Northampton and getting my finger caught in the door. Someone came in, my finger got crushed and I lost part of it.

My mother came to visit us several times when we were living there, and in fact we weren’t there for very long. It turned out that the terror and devastation that everyone had expected to be unleashed upon London had failed to materialise. As far as the British public was concerned, nothing really seemed to be happening. There were no aircraft flying over the capital. No bombs. No troops were mobilised. This new war with Germany was labelled the ‘Phoney War’. And so, in common with many other young refugees, after six months of living in Northampton with Mr and Mrs Ballos, my sisters and I returned to the family home in Willesden.

Of course, the Phoney War was anything but! On 7 September 1940, a year after war had been declared, German bombers began a sustained period of aerial raids over the capital. The Blitz had started. Our home in Willesden was no longer safe, so I was evacuated for a second time – not to Northampton on this occasion, but to Wales.

My new home was a small coal-mining village called Nantyffyllon, near Bridgend in South Wales. I was housed with a lovely family who, although they didn’t have much money, certainly had a good deal of self-respect. Every Sunday, they would get dressed up in their very best clothes for church – a tradition that seemed rather unusual to me at the time, but which I liked. I was made to feel very much part of that family. But I suppose, being just nine years of age, it was inevitable that I should feel homesick. I was certainly too young to feel particularly terrified at the prospect of returning to the Blitz. So that’s exactly what I did. I remained in Nantyffyllon for no longer than three or four months before returning to Willesden where, for the bulk of the war, I found myself in the thick of the Blitz and all that it entailed. Small wonder my education was disrupted, and that I found school very difficult.

There was no way my father could have afforded to pay for me to be educated privately, so I had three options in terms of my schooling. At the age of eleven, I could try for a grammar school. This was the option for those who were very strong academically, not for those like me who struggled at school. At thirteen, you could take an examination to get you into a technical college. Or you could see out your time at a secondary modern and, at the age of fourteen, it was time to get a job.

I went the secondary modern route in 1942 when I was eleven. There I learned the three Rs (reading, writing and arithmetic), plus a little history, geography and English – all taught by the same teacher because what we were learning was nothing like as advanced as the grammar school kids. We were in and out of air-raid shelters. This was very disruptive to our education, and it meant that some of my strongest memories of my formative years were little to do with schoolwork and more to do with the arrival of the dreaded doodlebugs.

The doodlebugs – or the V-1 flying bombs to give them their proper name – were the scourge of London in 1944. They looked rather like a small aeroplane, with no pilot. The Germans launched thousands of them against Britain. They were fitted with a special guidance system and kept flying until they ran out of fuel. Then they fell from the sky and exploded where they hit the ground, with potentially disastrous consequences. Anybody who lived in London during that period will remember the sound of the doodlebugs: the tremendous, screaming roar of the engines that made you shake as they approached, and the sudden silence that meant they were falling from the sky and that any moment there would be a terrific explosion. If you heard the doodlebug fly overhead, you were safe; if you heard the sudden silence, it was time to worry.

The doodlebugs were a terrible weapon and the British did all they could to destroy them before they reached London. Anti-aircraft guns were positioned from the North Downs to the South Coast in an effort to bring the bombs down before they reached highly populated areas. Some were shot down over the Channel by the RAF. Barrage balloons were deployed in the hope that the bombs would become entangled in their tethering cables. But inevitably, many doodlebugs made it to the capital. I well remember the day in 1944 when one of them landed near Willesden Green station, not far from where we lived.

Having joined the Cub Scouts when I was eight, I was now a Boy Scout. I saw it as my duty to help the war effort in whatever way I could. It must have been early in the morning that the Willesden Green doodlebug hit, because when it happened I spent the whole day helping to clear up the terrible mess it had caused. (Doodlebugs didn’t cause deep craters. Instead, they inflicted considerable damage over a very wide area.) I was only thirteen years old, but I was out there from first thing in the morning until eight or nine o’clock at night. By that time, as you can imagine, I was absolutely filthy from picking through the wreckage of burning houses and the general debris. I returned home and climbed straight into the bath.

I was alone in the house that night. There was a special roster during the war which meant that from eight in the evening until eight in the morning the streets were patrolled by adults carrying a bucket of sand, a bucket of water and a stirrup pump. Known as fire-watching duty, this was a very important job since the Germans were not only dropping doodlebugs on London, they were also dropping incendiary bombs. These contained highly combustible chemicals and were dropped in clusters – or ‘breadbaskets’ – in order to spread fires across the capital. It was the job of those on fire-watching duty to call in any fires to the fire brigade, and to extinguish whatever they could. I was alone that night because my mother and father were on fire-watching duty.

I sat in the bath, scrubbing off the dirt after my gruelling day clearing up after the doodlebug. As I was washing, I happened to look out of the bathroom window. Even now, more than seventy years later, I can picture what I saw as if it were yesterday. The house opposite us was on fire: a smouldering, burning blaze.

I jumped out of the bath, dried myself as quickly as I could and pulled my Boy Scout uniform back on. Then I sprinted from the house and rushed across the road to see what I could do to help. It was only then that I looked back over my shoulder to see that our own house – from which I had only just escaped – was also on fire. The Germans had dropped a basket of incendiary bombs on our street. If I hadn’t jumped out of the bath to go and help our neighbours, the chances are that I would have been killed in what was fast turning into an inferno.

My parents came back from fire-watching duty to find their own house in need of the fire brigade. I can only imagine how my father must have felt, watching everything for which he had worked so hard go up in flames. He certainly wasn’t going to let it all be destroyed without a fight.

For as long as I could remember, my father had collected antique silver. He was extremely knowledgeable about the subject and would spend hours at the house of a silver dealer in the next road, going through the history of each piece and buying those items that particularly interested him, and which he could afford. It wasn’t an especially valuable or important collection, but I believe it gave him a great deal of pleasure, and as a young boy I was transfixed by it too. So much so that, as I saw the flames spread through our house, my thoughts, like my father’s, immediately turned to that silver collection. He and I rushed into the burning house. I managed to locate a pair of old silver candlesticks that formed part of his collection. My dad got his hands on an antique table. We rescued those pieces, but that was as much as we could do. It was impossible to get back into the house for a second time; it was simply too hot.

Our house burned to the ground that night. I had spent the previous day clearing up the devastation of somebody else’s misfortune, now it was our turn. The next morning, my dad and I embarked upon the grim work of picking through the wreckage of our own home. I don’t know what my parents must have been feeling that day. A mixture, I suppose, of horror that their home had been destroyed, and relief that their family was safe.

I had celebrated my Bar Mitzvah about two weeks previously. It had been a small affair. Although Jewish by tradition, we were not an especially religious family. We obeyed the kosher rules, though, and I sometimes went to Hebrew classes, although these were sporadic because of the war. My Bar Mitzvah had taken place at a local synagogue. Afterwards, a few people had come round to the house for a simple party, and I had received some small gifts – prayer books, pens and trinkets. Those gifts were all lost in the fire. In the days and weeks that followed, some people were very kind and replaced the gifts they had given me. But of course, most of our belongings could not be replaced. I remember quite clearly that Dad’s prized silver collection was among the rubble, but those antique objects he loved so much had simply melted in the flames. We collected four sackfuls of the shapeless molten silver. It was now good for nothing other than selling for scrap, which is what we did.

Our family home flattened, we moved to a house further up the road. With me having only just escaped with my life when that bomb fell on our first home, we were now more diligent about taking cover when the doodlebugs came. Many people disappeared down the Tube stations when the air-raid warnings sounded. Others had Anderson shelters in their gardens. These were corrugated iron sheets bolted together with steel plates at either end, half-buried in the ground with a thick layer of earth heaped on top. But the Davidson family used neither of these options. The house opposite us had a cellar. When the doodlebugs arrived, we used to rush down into that cellar and sleep there. I’m not sure it was a particularly clever idea, because if the house was hit, there was a good chance we’d have been trapped or worse. Thankfully, though, that never happened. The remainder of the war passed, for us, in relative safety.

* * *

I left school in 1945 at the age of fourteen. My father couldn’t have afforded to send me to a private school to continue my education, and I think I probably wanted to leave school anyway. There was, however, no possibility of taking life easy from that moment on. I may have been just a boy by today’s standards, but in 1945 it was quite normal for a fourteen-year-old to go out to work. So, thanks to the good offices of a nextdoor neighbour, I found myself a position in the City, working for a garment manufacturer.

It was a proper job. Each morning, I would leave the house in time to catch a seven o’clock train from Willesden Green to Baker Street. There, I would change trains to be in the City by eight o’clock, and I was usually there until six at night. It was hard work. There was no goods lift at the premises where I worked, and part of my job was to drag heavy materials up and down the stairs. Getting them down was easy enough – you just rolled them – but taking them up the stairs was backbreaking work. I certainly felt that I’d earned my first pay cheque of thirty shillings. It was a lot of money in those days, at least it seemed that way to me. But I suppose I was beginning to learn an important lesson about business: if you want to earn a lot of money, it is better if you work for yourself.

I stuck at that job for four years, all the while living with my parents in Willesden Green. As the years passed, my responsibilities grew. I became in charge of the trimmings department. My job was to supply the correct materials and have them delivered to the ‘outdoor workers’ who were actually making the garments. If they were making fifty articles, I’d ensure they had sufficient material – shoulder pads, buttons and the like – to make those fifty articles. (I was reasonably liberal in what I gave them, however, and so they were generally in a position to make extra clothes, which they called, for some reason, ‘cabbage’!)

In 1948, the National Service Act altered and extended post-war British conscription. The age of service became eighteen to twenty-one and the length of service became eighteen months. This applied to all healthy men who were not registered as conscientious objectors (COs). At the age of eighteen, therefore, I was obliged to embark upon my National Service. It was quite common for young men of my age to try to dodge their conscription. They would claim they were not healthy enough, or come up with some other ruse that meant they didn’t do their eighteen-month stint with the armed forces. However, I felt strongly that, since my parents had been allowed to come and live in the UK, it was important that I should be prepared to do my bit. So, in June 1949, I stopped working at the garment manufacturer, and joined the air force.

There was an RAF camp in West Kirby, Cheshire. It was there that I spent my first twelve weeks. It didn’t matter what your eventual role would be in the RAF, everyone had to perform an initial three months of military drill, or ‘square-bashing’, as it was known. We were billeted in pre-fab huts, each housing about twenty men. They provided very basic accommodation, with a coke fire in the middle and lines of beds along both sides. We soon learned how to make those beds very precisely every single day when we got up. The officers regularly came to inspect them, and if your bed was just an inch away from perfect, you’d be in big trouble. Discipline at RAF West Kirby was notoriously strict. Our drill master was a corporal who used to scream and shout at the top of his voice. It could be quite alarming. And in the time-honoured fashion, you had to polish your boots until you could see your face reflected in them. It wasn’t my forte, so I used to get someone else to do mine for me – some things never change, my wife says!

I did, however, get very fit. As part of our square-bashing, we would be sent on fourteen-mile runs with a full pack and rifle. It’s impossible not to get in shape when you’ve done a few of those, so I was in good condition by the time my basic training was over. Having completed my twelve weeks, I was assigned to the balloon unit at RAF Cardington, Bedfordshire. It was here that they used to house the RAF’s barrage balloons – the same instruments used during the war to protect against the doodlebugs. My overriding memory of Cardington is of the enormous hangars that were built to house the R101 airships. There were no longer any of these, so the hangars had been reassigned to the balloon unit. And in fact, even though this was the RAF, there was only one aeroplane in the entire unit. A Tiger Moth, it was flown by an absolutely crazy Polish pilot – he used to take people up in it and scare them senseless. One day, he came up to me and said, ‘Right, Davidson, it’s your turn.’ I didn’t want to chicken out, so I climbed into the Tiger Moth and let him take me for a spin. Literally. He flew upside down, looped the loop and did every piece of aeronautical acrobatics you can imagine. When we came back down to earth I was absolutely white, and that was the extent of my exposure to aircraft during my stint in the RAF.

For the rest of the time I worked in the office, where one of my jobs was writing out the orders for the day using a stencil. It was not very taxing work but I was happy enough to be doing my bit. And it was during my time in the air force that my entrepreneurial streak started to show itself.

In the 1950s, rationing was still in force. There were certain luxury items that, even though they weren’t rationed, were particularly hard to come by. One of those items was whisky. Since I was doing my military service, I was able to do my shopping in the NAAFI, where I was able to buy whisky at a fixed price of 30 shillings, or £1.50. I would buy a couple of bottles at a time, but rather than drink them, I would take them to London whenever I had a day off. In London I was able to sell my whisky for more than double the price I’d paid. I’ll admit now that such entrepreneurship was not strictly legal, but nobody ever queried what I was doing and the NAAFI seemed perfectly happy to keep selling me the Scotch.

Quite soon, I had built up a substantial sum ‘enough, in fact, to buy myself a very old Lanchester car, which cost me £50. This meant that I was able to drive down to London whenever I had a free weekend. My newfound mobility soon caught the eye of my commanding officer. He was an old wing commander whose habit was to leave the RAF base at Cardington on a Thursday and return on a Tuesday, spending the intervening period in London. When he saw that I was the proud owner of a car, he asked if I would give him a lift to London. I obliged, of course, and as I dropped him off in town, he said, ‘See you Tuesday, then, Davidson?’ Fine, I thought. I stayed in town until the following Tuesday, picked up my CO and drove him back to Cardington. Before too long, this became a regular schedule. I was back and forth to London, chauffeuring the Wing Commander and spending long periods of time in the capital, rather than at the air force base.

I was originally only supposed to spend eighteen months in the air force. However, the Korean War broke out while I was doing my National Service and so that period was extended to two years. I had no real complaints. With my newfound entrepreneurship, and my role as the CO’s chauffeur, it would be fair to say that I had a much easier time than many in the RAF.

* * *

I left the air force on 23 June 1951, exactly two years after I had entered. I was twenty years of age and frankly, unemployable. My education hadn’t been great; I’d spent four years doing unskilled work in a textile factory and my time in the RAF had been profitable thanks to my whisky sideline, but hardly improving. I had no trade, no profession. My life stretched ahead of me and I didn’t really know what to do with it.

I was still living with my parents. My father knew some people who ran an estate agency in Kilburn and he persuaded them to give me a job. I only lasted a couple of weeks of running around and showing people houses, but it opened my eyes to an exciting new world: the world of buying and selling properties. Property trade people were constantly coming in and out of the office, and I remember thinking to myself that this seemed like an interesting business.

Being an estate agent wasn’t my calling, but I was beginning to have an inkling that maybe the property business was. So I left that job and joined forces with my father.

I was very close to my father. It was hard not to be, because he was a wonderful man. And I learned something about business from him. Before the war, he had run a small but quite successful shipping business, shipping to South Africa. My sister Zelda, who contracted TB at an early age and never married, worked for that company until she retired in her sixties. My father and I worked together to build up a property business. Over the next seven years, we established quite a successful little operation, buying and refurbishing properties around London. We used to employ our own builders and part of my job was to drive a van around London, delivering materials to the builders so that they didn’t have to waste time fetching them themselves, or waiting around when they could be working.

Working with my father was the best apprenticeship I could have had, and not just in the ways of the property business. He was a very clever man, and a thoroughly decent one. I learned a great deal from him about how to treat other people. He was philanthropic by nature. Whenever anyone came to my father for help, they were never turned away empty-handed. He wasn’t a particularly wealthy man, in fact, he was rather mercurial, one day he was up, the next he was down. He never believed in insurance so when our house burned down during the war, he didn’t get a penny for it, and it was hard to know what his financial situation was from one day to the next. But he would always find a way to give help to those who needed it. He was well known for his generosity. If somebody came to him in genuine need, he would always help: sometimes that help would be financial, other times he would find another way of giving them assistance. The medieval Jewish philosopher Maimonides said that if you give a man a fish, he eats for a day, but if you teach a man how to fish, he feeds his family for a lifetime. That was also my father’s philosophy. He was always prepared to help someone gain the means to earn a living; he was always prepared to teach them to fish, and sometimes even to give them a fishing rod.

In the years that were to follow, I would take pains to remember my father’s willingness to help others in need, and try to adopt it into my own life. In the meantime, however, I was a young man in post-war London, doing what I could to earn a living with my father. When I wasn’t working, I was socialising. And in 1957, I found myself at a dance at the Brent Bridge Hotel in Hendon in the Borough of Barnet. It was here that I was to meet a young woman who would change my life. Her name was Brigitta. Like me, her family was not from these shores, and the story of her early years was a remarkable one.