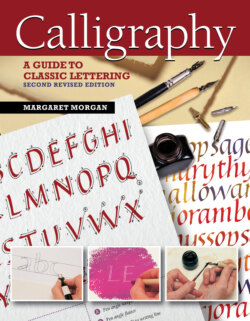

Читать книгу Calligraphy, Second Revised Edition - Маргарет Морган - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA Brief History of Western Calligraphy

The history of calligraphy, like many other histories, is cyclical: a new writing style is born, developed, and eventually dies or goes out of fashion; this is followed by rediscovery, reappraisal, and further improvement. What follows is just a general outline of how our current letterforms came into being.

roman capitals

Our familiar Western letterforms mostly stem from the Roman capitals (or majuscules) of the early centuries AD. These capitals were used for important and formal inscriptions. It is generally believed that the letters were first painted with a square-edged brush, then cut into a V-section in stone. The pattern of thick and thin strokes shows the calligraphic influence of the tools used to make them and the angle at which the tools were held. They weren’t “everyday” letterforms, though, as they required care and precision in the making. Square and rustic capitals fall into the same category. These early book hands were used for writing out classical texts. They were slow to write and required much pen manipulation to achieve the shapes—not natural pen-written forms at all.

Scribes gradually modified the capitals to economize on effort for the sake of speed; they took notes with their metal styli onto wax tablets, and, gradually, a cursive or running hand evolved. These tablets could be smoothed over and reused after the text had been transferred to a more permanent form, such as with reeds or quills on papyrus.

ROMAN CAPITALS

RUSTIC CAPITALS

SQUARE CAPITALS

uncials and half uncials

Between the 4th and 8th centuries AD, uncials developed out of the old Roman cursive hand, for writing out Christian texts. The forms were rounded, written with a slanted pen at a shallow angle, and showed the first real suggestion of ascenders and descenders. These are the first true pen-made letters, the shapes being created by the nature of the tool, not by trying to imitate anything else. They are clear, simple, and legible, and continue to provide inspiration to modern calligraphers. Later forms were written with a flat pen angle.

The spread of Christianity had much to do with the next development of written forms. The Roman Empire began to decline into chaos, incessant wars caused further difficulties, and much “pagan” classical literature was lost during the period we call the Dark Ages (550–750 AD). Cultural life in Europe more or less ceased as barbarians invaded and care of books and teaching passed to the care of the church. Half uncials developed independently during this time in Ireland and England from early examples of Roman uncials; they show clear ascenders and descenders. The most famous examples of the different types of “insular” half uncials can be seen in the Irish Book of Kells and the English Lindisfarne Gospels.

UNCIALS

UNCIALS WRITTEN WITH A FLAT PEN ANGLE

HALF UNCIALS

carolingian minuscules

The Age of Charlemagne was another important milestone. The Emperor Charlemagne was passionate about books and learning. His ambition was the revival of cultural life, for which books were essential. In 789 AD he decreed that all liturgical books should be revised. The Carolingian hand is characterized by a clear fluency and legibility that was ideal for these book texts. It was combined with the majuscules (built-up Roman letters, rustic capitals, and unicals) of antiquity, which were used for chapter headings, sub-headings, and the beginnings of verses—the hierarchy of scripts scribes still use today.

An English version of this hand was developed as an almost perfect model for formal writing—strong forms, logically made, with a consistent pen angle and easily read.

CAROLINGIAN MINUSCULES

CAROLINGIAN ENGLISH

gothic

By the 12th century, letterforms were becoming more and more compressed, and the soft flow of Carolingian gradually gave way to the heavy, angular, black letters of northern Europe known as Gothic. Materials became more expensive as demand for books increased, so the need to economize was greatly helped by the narrow Gothic letters that took up a lot less space but which were harder to read.

There were regional variations of the style across the European continent: the northern European quadrata had diamond feet and was very angular; rotunda, used in Spain and Italy, was much rounder in form; and the precissus Gothic of English manuscripts was characterized by its flat feet.

GOTHIC HAND

PRECISSUS

ROTUNDA

QUADRATA

the renaissance

SQUARE CAPITALS

During the Renaissance period in Italy (c. 1300–1500), there was a resurgence of interest in classical literature, and Italian scribes rediscovered the Carolingian minuscule. They also studied the Roman inscriptional letters and Bartolommeo San Vito revived the use of square capitals, developing his own distinctive style. Humanist minuscules, closely based on Carolingian, with their rounded forms, were very legible, dignified, and perfectly suited to formal texts.

HUMANIST MINUSCULES

What we now call italics also emerged at this time. Written with a slight slant and fewer pen lifts, italics were oval in form and flowed elegantly and relatively swiftly from the pen, making them ideal for secretaries writing documents at speed. Italics eventually evolved into copperplate script, where thicks and thins are made by applying degrees of pressure to a pointed nib, a move away from true pen-written forms.

HUMANIST ITALICS

calligraphy in modern times

Printing with movable type was invented around the mid-15th century, but printing didn’t entirely destroy the art of penmanship. Letters, patents, and diplomas were still produced in the traditional way. However, much of the craft fell out of use for almost two centuries, until William Morris rekindled interest in pen-lettering for the Arts and Crafts movement in the 19th century. Morris championed the cause of the craftsman-made objects in an age of increasing mass production, putting his studies of old manuscripts to good use when he set up his Kelmscott Press in 1890 in order to print beautiful and individual books. The real breakthrough for calligraphy came with the researches of Edward Johnston during the early part of the 20th century. His painstaking work brought about the rediscovery of broad-edged nibs and their importance in the development of the Western alphabet. His influence spread throughout Britain and into Europe in the 1940s and 50s, as well as to the United States.