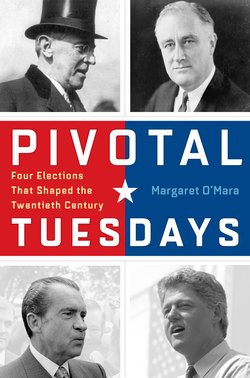

Читать книгу Pivotal Tuesdays - Margaret O'Mara - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

The Great Transformation

In the early morning of 18 June 1910, the ocean liner Kaiserin Augusta Victoria steamed into a fog-shrouded New York Harbor. The mist and intermittent drizzle of the morning had not kept a large flotilla of boats—from battleships to pleasure cruisers—from crowding the harbor, nor had it dissuaded the thousands of people who lined the streets in anticipation of the day to come. For the liner Kaiserin was bringing home former president Theodore Roosevelt, who was returning to the United States after more than a year overseas. Roosevelt was not only New York City’s favorite son, but a beloved national figure. On African safari for eleven months, and then on a tour of Europe for another four, he had been gone but hardly forgotten. Instead, his celebrity seemed to have increased over his prolonged absence.

The celebration that followed on that June day showed what a major public presence the ex-president continued to be, fifteen months after he turned over the White House to his handpicked successor, William Howard Taft. American flags waved as the day turned sunny. Roosevelt paraded down Manhattan streets, tipping his top hat to the jostling spectators, as policemen held back the eager crowds. A band played “Roosevelt’s Grand Triumphal March,” specially commissioned for the occasion.

On an outdoor stage festooned with bunting, he gave a classic, rousing speech to the assembled throng. Immediately below, reporters scribbled furiously in their notebooks, composing hyperbolic accounts that appeared on the front pages of newspapers from coast to coast. “Well, He’s ‘Back from Elba,’” proclaimed a banner headline in the Tacoma Times in far-off Washington State, calling it the “greatest welcome in the nation’s history.”1

Figure 1. Theodore Roosevelt’s triumphal return to the New York City after many months abroad made front-page news across the country. Tacoma Times, 18 June 1910, 1.

Political leaders also showered Roosevelt with praise. In the pages of a leading national magazine, President Taft gave the returning leader a flattering welcome. “After the heavy cares of the presidential office for eight strenuous years, he sought rest by contrast in the depths of the African forest and in great physical exertion in the hunting of large game,” Taft wrote. “His path since the time he landed in Europe until he sailed has been a royal progress,” a rapturous reception that “shows the deep impress his character, his aims, and his methods as a civil and social reformer have made on the world at large.”2

In a letter Roosevelt wrote Taft two days later, he could hardly contain his glee at the rapturous reception, even as he professed a desire to stay away from public life. “I am having a perfect fight to avoid being made to give lectures, and even of the invitations I have accepted there are at least half of them I wish I had not.”3

If bets were being made in June 1910 about the man most likely to win the presidency in 1912, the good money was on Theodore Roosevelt. The odds weighed in his favor not only because of his fame and biography, but also because of the weakness of any other possible contender. Chief among the weak was the incumbent in the White House. TR would have been a hard act for any politician to follow, but it was doubly difficult for Taft—amiable, intelligent, but lacking the political instincts and personality of his predecessor. His political missteps on bedrock Republican issues like the protective tariff had shaken the faith of both the GOP leadership and key constituencies. His more cautious and incremental approach to progressive issues like corporate regulation and conservation had alienated those who desired reform.

On the other side of the aisle, discord and frustration consumed the Democrats. The party had run the same man—William Jennings Bryan—as their nominee in three of the previous four presidential elections. He had lost every time. Grover Cleveland had been the only Democrat elected president since the Civil War. Although Bryan’s fiery populism had roused mass support among discontented farmers and working people, it failed as a national political strategy. The inroads that Democrats had made into some traditionally Republican states of the Northeast and Midwest during the Cleveland years had dissipated, and the Party now struggled to rebuild a coalition that could win the White House.4

Making the landscape even rockier for the two major parties were independent political movements bubbling up on the leftward end of the political spectrum. The Socialist Party was the most powerful among them, having brought together a range of left-leaning groups and ideologies into a political organization with a powerful and persuasive message about the inequities of industrial capitalism. The Socialist leader, Eugene V. Debs, had run for president in 1904 and 1908 with impressive, if not election-altering results.

Yet seasoned political observers know not to predict election outcomes too far in advance. The odds-makers of July 1910 might have been amazed to learn that the 1912 race would go to a man who, on the day of TR’s triumphant homecoming, had not yet been elected to political office.

Woodrow Wilson was a scholarly type who, although politically savvy, disliked the sorts of political spectacles Roosevelt relished. A Southerner of moderate-to-conservative views, the highest office he had obtained prior to 1910 was the presidency of Princeton University, from which he had rather unceremoniously stepped down after attempting dramatic reforms of campus traditions and institutions. Despite this setback, Wilson had already started to build a national political reputation as a leading voice for a new kind of Democratic ideology—an alternative to the populism of Bryan, but one that still supported public action to curb the power of corporations and protect individual rights. To a national Democratic Party looking rather desperately for a fresh face, Wilson provided it.5

Two months after Roosevelt’s “return from Elba,” Wilson won the Democratic nomination for governor of New Jersey. In a spectacular fall campaign, he turned on the machine politicians who had been responsible for securing his nomination and ran as a modern reformer. In November, Wilson secured the governorship, part of a Democratic wave in the midterm elections that signaled deep trouble for the national Republican Party.6

In the two years that followed, the political fortunes of the four men who became the significant candidates of 1912—Roosevelt, Taft, Wilson, and Debs—shifted dramatically, as did those of the other men who tried, and failed, to win the presidency. Friendships frayed. Alliances imploded. And as their prospects rose and fell, as new people entered the battle and others faded out of it, these politicians engaged in a debate about the nature of citizenship, corporate power, and government responsibility that had not been seen before in American politics. The men and women who supported their campaigns joined in the conversation, helping turn the nation’s focus away from the political issues that had consumed the nineteenth century and toward the ideas that defined the twentieth.

This extraordinary election brought ideas into the political mainstream that had been considered radical only a few years earlier. It realigned both the Democratic and Republican Parties in subtle but significant ways, and showed the power of third-party insurgencies to disrupt—but not overturn—the two-party system. It demonstrated how far the system had come from the styles and methods of politicking that had characterized national races since the days of Jefferson and Adams, and institutionalized an entirely new breed of campaign rituals and strategies that had emerged at the end of the nineteenth century and became business as usual in the twentieth.

America Transformed

Like all presidential contests, the 1912 election only can be fully understood in the context of the changes the United States had experienced in the years leading up to it. And for this election, we must go back farther than 1910, or even 1890 or 1870, but all the way to the eve of the Civil War to comprehend the men who ran and the people who protested, organized, agitated, and voted for them.

A good place to begin is 5 November 1855, when future Socialist presidential candidate Eugene Victor Debs was born into a family of French immigrant grocers in Terre Haute, Indiana. The America baby Gene came into was a place where three of four people lived in the countryside or small towns. Most of them were farmers. No city in the U.S. had more than a million people.7 While new technologies like the mechanized loom and the cotton gin were transforming markets, and new transportation networks of canal and rail were enabling new flows of goods, people, and communication, most Americans lived according to preindustrial rhythms. People wore watches and consulted clocks, but local time was not standardized and remained governed by the rising and setting of the sun. Families like the Debses immigrated across oceans while native-born white Americans continually migrated westward across the continent, but travel was slow and news moved just as slowly.8

Preindustrial rhythms of life held strongest sway in the pre-Civil War American South, where well over 90 percent of the population were rural, the manufacturing economy was minuscule, and roads and railroads were far scarcer than in the North.9 This was the world into which Thomas Woodrow Wilson was born in December 1858, the son of a clergyman in Staunton, Virginia. Moving as a baby to Georgia, and then to South Carolina, Wilson had a childhood surrounded by war’s terror and its devastating aftermath.10

The human suffering and physical destruction wrought by the war propelled a turning point in America’s understanding of itself. Before the Civil War, the country had operated as a sometimes tenuously connected “union” of self-governing states with markedly different economies, demographics, and cultural sensibilities. Afterward, the country increasingly came to be understood as, and function as, a “nation” whose federal government wielded increasing power and whose citizens shared common values and culture. As historian James McPherson writes, “the war marked the transition of the United States to a singular noun.”11

The end of war also escalated remarkable changes already underway in the American economy. In the span of a few decades, the United States became an industrial colossus, home to some of the largest corporations and richest people on the planet. Rapid industrialization triggered foreign immigration and urbanization of unprecedented scale and speed. As the population swelled, a growing nation became a giant consumer market for products made in American factories.

Some of this change became evident well before the Civil War in New York City, where Theodore Roosevelt was born to affluent parents in October 1858. Always a polyglot, multiethnic metropolis, New York had become intensely more so since the 1820s, as waves of immigrants from Ireland and continental Europe arrived at its docks and stayed for good, squeezing into overcrowded tenements and urban slums. Many of these immigrants—and the millions who would follow them in the decades to come—went to work in the new factories that were growing up in New York and cities like it. Men, women, and children alike worked long hours, six days a week, in factory jobs that ranged from moderately to extremely dangerous. They worked for low pay, few benefits, and no safety net if they got injured on the job.12

One year before and a thousand miles to the southwest, William Howard Taft had been born into prosperity in the Midwestern river city of Cincinnati. While his family were not quite as rich as Roosevelt’s, they were nonetheless quite comfortable and politically influential. Taft’s father, Alphonso, was a powerful Republican who served in President Ulysses S. Grant’s cabinet as attorney general and as secretary of war. Both a political power broker and an attentive father, the elder Taft had high expectations of his son Billy. The younger Taft rose to them. Although he struggled with obesity throughout his life, he was a natural athlete and became a star baseball player in high school, only giving it up when his parents cautioned him not to neglect his academic studies. He excelled in those as well, winning high grades and following his father and half-brother to Yale in 1874.

By this time, teenage “Teedie” Roosevelt was spending hours in the boxing gym and on the wrestling mat in an attempt to bulk up his skinny physique. Gene Debs had dropped out of school to support his family and was working on the railroad, first as a painter and cleaner, and then as a locomotive fireman. Tommy Wilson was preparing to leave the Reconstruction-era South and head North to college.

By the mid-1880s, Taft was an assistant county prosecutor in Ohio. After graduating from Harvard, Roosevelt had dropped out of law school but still managed to get himself elected to the New York State Assembly. Wilson received one of the very first Ph.D.s in history and was a junior faculty member trying to write his first book. Debs had become a full-time labor organizer for his fellow railroad workers.

In these two decades of change in the four men’s lives, the United States was undergoing an extraordinary transformation. In 1869, the transcontinental railroad had linked the West and East coasts. In 1876, Alexander Graham Bell had filed his patent for the telephone, and in 1879 Thomas Edison had developed his first incandescent light bulb. Beginning in the 1880s, the predominantly Northern European character of the nation began to change with the arrival of new waves of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe. As new arrivals had done before and since, they took on the dirtiest and hardest jobs, from urban factories to Western mines and oilfields. An increasingly diverse United States became home to millions who brought with them new languages, cultural traditions, and political ideologies.

Everything grew bigger. Farm production doubled. The U.S. population tripled. The value of manufacturing became six times larger. Cities grew up and out; between 1860 and 1910, the number of people living in American cities grew from 6 million to 44 million.

America lacked the institutions and governmental organizations to cope with such massive growth. It was the apex of the era of machine politics in the cities, kickbacks and bribery in the U.S. Congress and the state legislatures, and chaos nearly everywhere else. As muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens put it in his 1904 expose of urban political machines, the debilitating effects of this “boodle”—aka, political corruption—were “so complex, various, and far-reaching, that one mind could hardly grasp them.”13

Figure 2. Joseph Keppler, “The Bosses of the Senate,” 23 January 1889. Political corruption accompanied the explosive growth of the American industrial economy after the Civil War, and many in the U.S. Congress fell under the sway of big railroads and big oil. Library of Congress.

Meanwhile, the firms that ran the railroads, owned the mines and oilfields, and controlled the factories grew into enormous corporations and conglomerates of extraordinary power and reach. Their power overshadowed that of the government. In 1891, the Pennsylvania Railroad had 110,000 employees. The entire U.S army was less than a third that size. Federal government spending per capita was about $129, less than 10 percent of gross domestic product.

The speed and scale of change, and the failure of American social institutions to manage it, spurred Americans of all classes, regions, and political ideologies to question the status quo and agitate for alternative approaches. While grassroots protest and reform movements had been part of American civil society since before the Revolution, fast and ubiquitous national and transnational communications networks allowed reform ideas to gather force more rapidly and widely than before. News of strikes and protests crackled across telegraph wires in moments, students returned from abroad with radical new ideas, newspapers printed fiery speeches, and magazine editors filled pages with long-form investigative reporting on the excesses of the era. Cheaper printing, far-reaching networks of road and rail, and higher literacy rates expanded publishing and readership.

Farmers and laborers in the Midwest and West cursed the far-off bankers and corporate titans whose stranglehold on markets drove down crop prices and drove up shipping costs. They mobilized locally in the 1880s through organizations like the Grange, and nationally in the 1890s through the Populist Party, using modern media and charismatic leaders to voice their discontent with the modern order. A new wave of Democratic leaders seized the opportunity to broaden the Party’s regional constituencies and pushed for the adoption of key Populist Party principles into its 1896 party platform as well as nominating Bryan, populist firebrand and powerful orator, three times running.

Yet with a Congress under the sway of corporate “boodle” and a series of White House occupants more beholden to party bosses than to changing the status quo, much of the reform energy prior to 1900 emanated from outside national political institutions. Critiques of the industrial order ranged from moderate to radical. Some began to advocate for some regulation of the monopolistic companies that controlled disproportionate chunks of the national economy. Others thought the only solution was to break up the corporate giants altogether. The most ardent anti-monopolists advocated property reform and mandatory wealth redistribution.

Working-class people went on strike and mobilized into labor unions. Their middle-class allies joined them in crusading for workplace safety, workers compensation, and child labor laws. Socialists, communists, and anarchists argued that the entire capitalist system needed to be replaced. Some resorted to violence to express their fury at the system, resulting in a number of acts of domestic terrorism, including the 1901 assassination of William McKinley—the act that propelled Theodore Roosevelt into the President’s Office. Women, who didn’t get the right to vote in most states until the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, played prominent roles in many of these movements, from the anarchist fringe to the “respectable” middle.

The four candidates of 1912 resided at different places in this spectrum of reform. Roosevelt entered politics in 1882 when elected to the New York State Assembly, believing that more men of his class—educated, enlightened—needed to become involved in what he called “the raw coarseness and the eager struggle of political life.”14 Wilson, in contrast, spent the first three decades of his career in academia. While conservative when it came to social issues like race relations, his long tenure outside formal politics perhaps made him bolder when it came to bucking the party bosses; by the time he ran for president, he would argue for breaking up business monopolies. William Howard Taft was a good Republican Party man, winning a series of plum judicial and administrative appointments as a reward for his competence and amiability. Although sympathetic to Progressive causes, he was a quiet, unshowy sort of reformer.

The rise of Eugene Debs, on the other hand, attested to the great anguish and political discontent among the working people who suffered the most in the new industrial economy. By the early 1890s, Debs had given up working on the railroad and instead was working to represent the interests of railroad workers, becoming head of the powerful American Railway Union in 1893. The following year, workers at the Pullman Company went on strike to secure better wages and working conditions. Pullman was America’s leading manufacturer of railway sleeping cars, a critical cog in the railway machine. Debs organized a nationwide railway boycott of the Pullman cars in support. Workers in railway yards across the country refused to couple the Pullman cars to trains. Engineers refused to drive them. The entire national rail system ground to a complete halt.15

The railroad was so important to the functioning of the national economy that the federal government intervened. Democratic President Grover Cleveland sided with Pullman, not its workers, and dispatched U.S. soldiers to Chicago to restore the peace. Although Debs already had exhorted his members to keep the main trains running and mitigate the worst effects of the strike, the Cleveland administration still sent him to prison for blocking interstate commerce. He emerged a national celebrity and a hero of the workingman. A lifelong Democrat, he was so disgusted at Cleveland’s actions that he switched to the Socialist Party, first running for president on its ticket in 1904.

By this time, the many currents of protest and calls for reform had started to have significant policy implications. While many reform movements (particularly those led by native-born, middle-class women and men) had their origins in religious and voluntary organizations, it was clear that meaningful reform needed more than churches and charities, settlement houses and orphanages. Only larger, public entities could tackle the multiple challenges created by industrialization. Government needed to do more.

Figure 3. Eugene V. Debs, 1912. Debs’s leadership of the American Railway Union during the Pullman Strike of 1894 made him a working-class hero and decisively shifted his political allegiance from the Democrats to the Socialist Party. His 1912 Socialist candidacy was his third bid for the White House. Harris & Ewing Collection, Library of Congress.

The initial push for a larger public role came in big cities, where such problems were most acute and painfully visible. Progressive reformers pushed to clean up corrupt local governments and establish professional civil service systems. Theodore Roosevelt burnished his reform credentials after being appointed to lead New York City Police Board in 1895, where he proceeded to clean up the corrupt institution and pass regulations dear to many reformers’ hearts, such as banning Sunday liquor sales. While the federal government remained largely on the sidelines, reformers within and outside state and local governments in the 1890s and 1900s enacted a range of measures from town planning to workers’ compensation to stricter child labor laws. Cities built infrastructure from bridges to parks, schools, housing, and water and sewer systems.16

The various efforts of middle-class reformers blended particular ideas about morality and correct behavior with a faith in large-scale organization and specialized “expertise.” American reform did not exist in isolation; similar movements and politics arose at the same time throughout the industrialized world, and in many instances American reformers took their cues and inspiration from European models. Often referred to as “Progressivism,” the reform impulse was not an organized political party nor was it a single ideology.17

With the ascension of Theodore Roosevelt to the Oval Office, Progressivism became more central to the national political conversation. After a long succession of rather colorless chief executives who toed the party line, Roosevelt impressed those longing for reform with his forceful personality and willingness to buck the authority of the Republican Party’s conservative leadership. While some of his actions as president were bold—particularly when it came to conservation of natural resources—others left Progressives wishing for more. He did not hesitate use his bully pulpit to call Wall Street bankers and corporate titans on the carpet, but he believed in corporate regulation, not breaking up monopolies altogether.

Roosevelt picked Taft to succeed him because he found him a fitting person to carry on his legacy. The same amiability and loyalty that had earned Taft so many good appointments encouraged Roosevelt to believe that Taft would do little to alter Roosevelt’s reformist agenda. TR had declined to run for a third term, but in Taft he envisioned a third term by proxy.

Within a few months, the new president proved him wrong. Perhaps the most grievous blow was Taft’s firing of Roosevelt’s close advisor Gifford Pinchot, who had been instrumental in creating the U.S. Forest Service and crafting a new federal approach to the management of lands and natural resources. When it came to corporate reform, Taft was actually a little more reform-minded than Roosevelt had been. But his political bumbling and reluctance to break with the GOP stalwarts on ossified approaches to trade and commerce gave many people—Roosevelt included—the impression that he was hardly the Progressive hero they wanted and needed.

In a world of increasingly advanced technology and complex organizations, it no longer made sense to have a U.S. government whose biggest agency was the Post Office. As Progressive era author Herbert Croly put it in 1909, “an American statesman could not longer represent the national interest without becoming a reformer.”18

It was in this atmosphere that the campaign of 1912 began. The United States had had a long and venerable tradition of small government and limited executive power. It was a testament to the incredible changes that had occurred over the four candidates’ lifetimes that they all agreed that more government action and regulation was necessary, and inevitable.

They just disagreed on how to get there.

The End of a Friendship

William Howard Taft seemed like an uninteresting president to many of his contemporaries. It might have been because he was uninterested in being president.

Taft’s greatest dream was to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court. After obtaining his law degree, his quick ascent in the world of Republican politics came not through winning elections but through a series of judicial and administrative appointments. He once wrote that his professional rise was due to having his “plate right side up when offices were falling.”19 Yet this self-deprecating characterization belied his true accomplishments. First appointed a judge in 1887, by the mid-1890s Taft had distinguished himself as one of the most prominent and well-regarded jurists in the country, often mentioned as a likely appointee to the Supreme Court. Only his youth—he was less than forty at the time—put him out of serious contention.20

By this time, Taft and Roosevelt had become good friends. Their age, class, and political outlook gave them much in common. Their radically different personalities, extrovert and introvert, complimented one another. In Taft, Roosevelt had an attentive listener and advocate; in Roosevelt, Taft had both entertainment and intellectual stimulation. In the beginning, Taft was the senior of the two, having been appointed by Benjamin Harrison to be the nation’s number-three lawyer, solicitor general, in 1890. Roosevelt had a relatively less important appointment, civil service commissioner. When William McKinley became president in 1897, Taft urged him to appoint Roosevelt assistant secretary of the navy.

That appointment became TR’s springboard to national political celebrity, as he famously quit his job the following year to lead a brigade of roughneck cowboys and mercenaries into battle in Cuba. Despite his middle age and the general unpreparedness of U.S. troops, Roosevelt and his Rough Riders won the Battle of San Juan Hill and catapulted into legend. Riding the wave of postwar celebrity, he became governor of New York. Yet Roosevelt’s thirst for reform made him a thorn in the side of Republican Party bosses in New York, and by 1900 this contributed to his being dislodged from a job he enjoyed into one that had far less influence: the vice presidency of the United States. One commentator observed that the preternaturally vigorous Roosevelt had little desire to be “laid upon the shelf at his time of life.”21 He ended up spending little time on that shelf, however. On 14 September 1901, an assassin’s bullet felled McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt moved into the President’s Office.

The Spanish American War had resulted in Taft getting a new job as well: governor general of the Philippines, one of the remnants of the Spanish empire left in U.S. hands after the guns had been silenced. From 1900 to 1903, Taft took on this high-stakes, high-risk job and—from the perspective of his bosses in Washington—excelled at it. He walked into a political tinderbox. Most Filipinos had little desire to exchange one colonial ruler for another, and had launched a fiercely fought nationalist rebellion that was, in turn, being quite violently repressed by the U.S. military. By the time he left, the Filipino independence movement had been quashed and U.S.-led social and political institutions were in place that maintained civic stability and protected American economic interests. The regime Taft established helped perpetuate U.S. control over the nation and its people for another forty-one years.22

By 1904, Roosevelt had pulled his old friend back home to become his Secretary of War, one of the most powerful positions in Washington. The job further strengthened the relationship between Roosevelt and Taft. After some public dithering about whether to run again in 1908 (he had only been elected once, and the two-term limit then was a tradition rather than a statutory limitation), Roosevelt decided to step aside. Taft—supremely competent, unfailingly loyal, a strategic problem-solver—seemed like an eminently sensible choice to carry on the TR legacy.

It was not easy to convince Taft to run; he still had the Supreme Court highest in his mind. “The President and the Congress,” he once said, “are all very well in their way … but it rests with the Supreme Court to decide what they really thought.” He had repeatedly denied, publicly and privately, that he would ever agree to be put in the running for the presidency.23 However, Roosevelt had an ally in Taft’s ambitious wife Nellie, who had been aspiring to the First Ladyship since her husband’s earliest days in politics. Faced with the combined persuasive powers of Teddy and Nellie, Taft agreed to do it. He later called the 1908 campaign “the most uncomfortable four months of my life.”24 He won, quite decisively vanquishing William Jennings Bryan, who would never run for president again.

The next day, Roosevelt sat down to write Taft a congratulatory letter that, while effusive, reflected the complicated nature of the two men’s friendship. Taft was the winner, but Roosevelt saw the victory as a validation of his own good judgment. “Dear Will,” TR wrote. “The returns of the election make it evident to me that you are the only man who we could have nominated that could have been elected. You have won a great personal victory as well as a great victory for the party, and all those who love you, who admire and believe in you, and are proud of your great and fine qualities, must feel a thrill of exultation over the way in which the American people have shown their insight into character, their adherence to high principle.”25

Within days, however, Taft began to disappoint Roosevelt’s high expectations. The note of thanks the president-elect wrote his predecessor in response expressed great gratitude for all Roosevelt had done to help the campaign, but it also gave some credit to Taft’s brother Charles, a Republican Party moneyman and political fixer. Roosevelt fumed. To him, Charlie Taft was a hack; Roosevelt was a statesman. Would Billy Taft be in the White House without Roosevelt’s endorsement and encouragement? Was this any way to repay a friend?

Rumors of rift started buzzing in the early months of 1909, as Roosevelt prepared to hand over the reins to his successor. And Roosevelt did little to stop them. “He means well and he’ll do his best,” he told a sympathetic journalist on the last day of his presidency. “But he’s weak.”26 With that, the ex-president steamed away on safari. He and Taft did not correspond for a year.

The real problem was bigger than a breach in etiquette. Theodore Roosevelt had a hard time not being president any more. He was fifty years old, healthy and energetic, and unemployed. He was hugely popular. He also was spending a lot of time thinking and absorbing new ideas as he traveled abroad. Touring Europe in the first months of 1910, he was presented by a range of political ideas and policy solutions more audacious and far-reaching than American reforms. The sweeping social insurance programs of Germany, the support for mothers and children in France, the worker housing programs of Great Britain: all these impressed Roosevelt in their scope and ambition. They presented a new potential for national government to intervene in the workings of markets, to remedy inequity, to promote economic security.

The speeches he gave on this European tour intensified in their bold proclamation of reformist ideas. In Paris, he talked of human rights being more important than property rights. In Oxford, he spoke about income inequality and the need for an “acceptance of responsibility, one for each and one for all.” While he refrained from prescribing solutions, he began to develop a more audacious, more compelling language around the need for reform. Coming from a leader of such charisma and passion, the progressive message that TR returned home with in the summer of 1910 was poised to win over American hearts and minds.27

In the meantime, the new president had been stepping into one public relations fiasco after another. He flip-flopped on critical issues like the tariff in ways that left pretty much everyone unhappy with him.28 And as his old boss moved to the left, Taft appeared to move to the right, joining in closer alliances with old guard Republicans in Congress. In reality, Taft and Roosevelt were not that far apart on many issues, but political flubs and media missteps tended to magnify their differences. One aide remarked that Taft “does not understand the art of giving out news” in the way his predecessor had done so masterfully.29

Adding to Taft’s public relations woes was the mounting gossip about the sour turn that the Roosevelt and Taft friendship had taken. In an effort to quell them, Roosevelt orchestrated an elaborate photo opportunity by paying a visit to Taft at his summer home in Massachusetts on his return to the United States in the summer of 1910—accompanied by 200 scribbling reporters. The New York Times reported the meeting as “a warm embrace” involving much laughter and backslapping.30 Yet this was merely a photo op. The restless Roosevelt continued to complain privately to friends about Taft’s job performance.

The Taft-Roosevelt rift was personal and sometimes petty, but it became politically significant because it mirrored a broader identity crisis in the Republican Party as the issues that drove politics in the nineteenth century gave way to the debates that would shape politics and policymaking in the twentieth. Mainstream Republicans of 1912 were the party of industry and enterprise, and they were supporters of tariffs on foreign imports to protect domestic manufacturing. Having controlled both Congress and the White House for most of the late nineteenth century, the mainstream GOP was less a party of reform than one of status quo. Yet this relative conservatism was hardly a laissez faire, small-government philosophy. The Republicans were, after all, the party of Reconstruction, of major public infrastructure projects like the transcontinental railroad and the land grant colleges, and of major welfare programs like the veterans’ pension system. In 1912, the advocates of small government and states’ rights hailed from the Democratic Party, not the Republican.

Republican constituencies in 1912 also were far different than what they would become over the course of the twentieth century. In 1912, the GOP was still the party of Lincoln. African Americans usually voted Republican, when they could vote, but racially motivated maneuvers like poll taxes and literacy tests in the Jim Crow South had largely disenfranchised the Southern black population. The key to the Republican Party’s dominance of national politics in the post-Civil War years was its strong presence in the urban Northeast and Midwest, where the majority of Americans lived at the time. Yet by the beginning of the twentieth century, the growing size of the Republican base in Western states was beginning to shift this regional hegemony. The manufacturing-heavy Northeast and Midwest was the bastion of pro-tariff, pro-business Republicanism. The agrarian Far West represented a vastly different set of interests, ones that blended anti-monopolist politics with crusading middle-class moralism.

While Republicans had held majorities in a political system that was staggering in its level of corruption and favoritism, the GOP was not simply a party of cronies. It was the party of Progressives. Many of the middle-class, native-born reformers came from the base of the Republican electorate, and had very different ideas about the party’s destiny. Many of these new Progressive voices came from West of the Mississippi. The GOP, they argued, no longer should be the party of modest market regulation. It should be the party of action. The defining issues of modern politics, the progressive faction argued, was cleaning up an electoral process that favored party insiders, and replacing patronage with efficient, professionalized government bureaucracies. The government was the only possible counterweight to the power of the huge industrial corporations, and government needed to pass and enforce more aggressive laws protecting workers, conserving natural resources, and alleviating poverty. They generated momentum for reform at all levels of government that began to shift the Republican Party from the one of the status quo to the one of hope and change.

The Republicans were not the only political party with an identity crisis on its hands. The Democratic Party had multiple constituencies with quite different visions of the American future. By 1912, the Democrats’ big tent encompassed the populists of the Great Plains and West who were demanding national government action on monetary reform and regulation of Wall Street. It included Southern whites with a huge economic and social stake in keeping Jim Crow intact and who were suspicious of a powerful central government that might trample on states’ rights to maintain segregation. Foreign-born immigrants also voted Democratic, in part because of the powerful influence of Democratic machines in large cities. And, like the Republicans, the Democrats included some Progressive reformers. These reformers argued that the Democratic Party, not the GOP, could be the standard-bearer for a more activist central government, for better lives for working people, and for breaking up the monopolies and ushering in a fairer capitalist order.

After his return from abroad in 1910, Teddy Roosevelt had seized on the cresting Progressive wave and went on a nationwide speaking tour, sounding more progressive with every stop. More must be done to keep corporations out of politics, Roosevelt told mesmerized crowds of five, ten, and twenty thousand. Corporate directors whose companies broke the law should be subject to prosecution. The national government must do much, much more. In Osawatomie, Kansas, on 31 August, Roosevelt gave the definitive speech that gave this new philosophy a name—the “New Nationalism”—and declared it would not only fix the problems of industrial capitalism, but also allow the nation to transcend its vexing issues of sectionalism, corruption, and class divides.31

Yet while barnstorming the country like a presidential contender and drawing massive and enthusiastic crowds, Roosevelt continued to swat away all suggestions of running for president. “There is nothing I want less,” he told newspaper editor, leading progressive, and close ally William Allen White as 1910 drew to a close.32

Reluctance to challenge his old protégé Taft seemed the least of the reasons Roosevelt was refraining from a run. Like presidents before and after him, he worried that he might not win. New winds were blowing, but Roosevelt didn’t think the Republican Party was quite ready to swing to the progressive side. He figured he would have better luck remaking his party in 1916. Given the opposition within the party to progressive ideas, Roosevelt worried that, even if he won in 1912, he might ultimately risk his legacy. “I do not see how I could go out of the presidency again with the credit I had when I left it,” he confessed to White. But, as all savvy politicians do, he left the door open. If his supporters and friends felt he was the only hope for the progressive cause, “it would be unpatriotic of me” not to stand for election.33

Figure 4. William H. Taft and Theodore Roosevelt, 1909. Taft was Roosevelt’s hand-picked successor for the White House, but by the early months of Taft’s presidency the two men’s political alliance—and personal friendship—was in tatters. Brown Brothers, Library of Congress.

Whether motivated by duty, ego, or a combination of both, Roosevelt found it increasingly hard to resist the lure of the campaign trail as 1912 neared. As the next chapter will show, this had huge consequences.