Читать книгу Pivotal Tuesdays - Margaret O'Mara - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

The process of election affords a moral certainty, that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications. Talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity, may alone suffice to elevate a man to the first honors in a single State; but it will require other talents, and a different kind of merit, to establish him in the esteem and confidence of the whole Union.

—Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 68, 1788

The newspapers were merciless. One candidate for president was a “libertine” with a “lust for power.” He and his followers were “discontented hotheads” who had “long endeavored to destroy the Federal Constitution.” If he was elected, warned one political adversary, “murder, robbery, rape, adultery and incest will all be openly taught and practiced, the air will be rent with the cries of distress, the soil will be soaked with blood.”1 Similarly sharp language zinged back toward his opponent, the embattled incumbent. The sitting president was a man of “limited talents” who was not a defender of democracy, but the head of a “monarchic, aristocratic, tory faction” that only cared about the rich and powerful elite.2

As the election got tighter, the allegations became more personal. Drawing-room whispers about the challenger’s affairs with his female slaves became printed denunciations of his “Congo Harem.” His earlier expressions of religious tolerance stoked allegations that he was a “howling atheist” who would confiscate the Bibles of God-fearing people. Perhaps the lowest blows of the campaign fell on the incumbent, whom one scribe accused of having a “hideous hermaphroditical character, which has neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman.”3

Although modern conventional wisdom has it that American presidential elections are nastier and more polarizing than ever, few recent elections can compare with the down-and-dirty partisan warfare on display in the election of 1800. The targets of all this mudslinging: Federalist president John Adams and his Democratic-Republican challenger Thomas Jefferson, two now-beloved architects of the American Revolution.

Once great friends, the men had become bitter political enemies with profoundly different views about how the young nation might reach its destiny. On the one hand, Adams and his Federalist allies believed that the future of the young nation was in its cities and in commerce, and it needed a strong central government to do things like acquire new territories and regulate foreign trade. On the other, Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans believed that the heart and soul of the United States was in the agricultural countryside, and that all should be done to protect the independent interests of the yeoman farmer. Geography divided them as well. The Federalists had strongholds in the towns and cities of the North; the Democratic-Republicans drew support from the slave-owning South and the hardscrabble Western frontier.

The stakes in 1800 seemed extraordinarily high. In the first years of the new republic, the two-party system as we know it today did not exist, and there was a reason for that absence. Many of the Founding Fathers believed partisan elections did more harm than good. “The common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party,” George Washington had remarked as he left office in 1796, “are sufficient to make it the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it.”4 The election of 1800 was only the nation’s second partisan election, and the first that resulted in a turnover of the presidency from one party to another. The toxic campaigning and divided polity resulted in a deadlocked election that had to be decided by the House of Representatives barely two weeks before Inauguration Day. Jefferson won, and called his victory over the incumbent “the Revolution of 1800.”5 While subsequent observers have argued over the degree to which the moment truly was a “revolution,” the election precipitated the passage of the 12th Amendment to the Constitution, which took the responsibility of breaking a deadlock away from the politics of the House and established a separate, ostensibly nonpartisan Electoral College.

In the two centuries since, many presidential election contests have provided ample evidence that partisan politicking can bring out the worst in human nature. Personal attacks, apocalyptic pronouncements, and intricate political machinations have been hallmarks of nearly every competitive presidential race. The growth of modern media has further amplified the less appealing qualities of the American electoral process. By the time it was completed, the 2012 presidential contest between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney had lasted more than two years, involved campaign expenditures of close to $2 billion, unleashed thousands of television hours of vitriolic campaign advertising and political punditry, and lit up the Internet with heated commentary and name-calling.

Yet the Obama-Romney race also demonstrated that—just as in 1800—the American democratic system could withstand the blows of partisan warfare. In referring to the election that made him president as “the revolution of 1800,” Jefferson believed that the basic freedoms for which the American Revolution had been fought were imperiled by the rise of the Federalist Party and its leaders like Adams and Alexander Hamilton, who had advocated for a stronger central government, trading relationships with Great Britain, and more limited democracy. Jefferson saw his election as bringing about a restoration of the founding principles of limited government and individual liberties. Power moved from one party to another without a drop of blood being shed. It was, in his mind, the true culmination of the revolution of 1776.

Historians have since argued over the degree to which 1800 was as significant a turning point as Jefferson liked to portray it, and debates continue to rage over whether his small-government vision was, in fact, truly the Founders’ intent. What is indisputable, however, is that a fiercely contested election did not shatter the fragile new republic, as some observers worried. Candidates fought, political operatives schemed, but the system survived and thrived.6

More than that, elections from the age of George Washington to the age of Barack Obama have showed the power of presidential contests to provoke and inspire mass engagement of ordinary citizens in the political system. Elections are expressions of national identity, and mirrors of individual desires and priorities. No matter how frustrated or disinterested voters might be about politics and government, every four years the attention of the nation—and the world—focuses on the candidates, the contest, and the issues. As elections have become tighter, and the money spent on them greater, attention and enthusiasm about them has increased rather than decreased. George Washington may not have approved, but the partisan election process has been a way for a messy, jumbled, raucous nation to come together as a slightly-more-perfect union. As they cast their ballots, ordinary people make history.

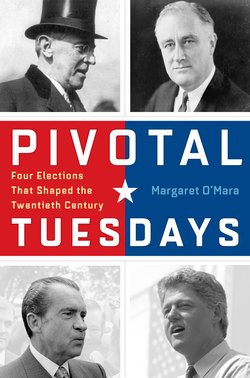

This book looks back at four presidential races of the past hundred years to show how this history was made. It begins with the rowdy four-way contest in 1912 between Teddy Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, Eugene Debs, and Woodrow Wilson that resulted in Wilson’s victory. It continues with Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal campaign and his win over Herbert Hoover in 1932. The third case profiles the eventful and tragic campaign of 1968 and the election of Richard Nixon, and the final story follows the three-way race that led to Bill Clinton’s victory in 1992.

Why these four elections? Why not 1948, when Harry S Truman beat Thomas Dewey in perhaps the greatest election upset in American history? Or 1980, when Ronald Reagan’s election ushered in a new age of conservative resurgence? Part of the reason is personal: having worked on the 1992 Clinton campaign, I could bring an eyewitness perspective to an election, and an era, that historians are now beginning to explore. Yet there are larger reasons as well. I wanted to use elections as a way to explore bigger changes in American society, from industrialization and urbanization, to the crisis of the Great Depression and response of the New Deal, to the rise of the Sunbelt and the advent of the high-tech economy. These four elections thus help tell us about more than who got elected and why; they illuminate the trajectory of the nation’s experience through what publisher Henry Luce proclaimed “The American Century.”7

While I was writing this book, it became clear that everyone has an opinion about the most important presidential elections in history; indeed, debating the merits of one’s list is part of the fun of being a political junkie. But there is more to it than personal preference. Many a former political science major will be familiar with the theory of “realigning” elections, which argues that certain years have been watersheds in terms of both partisan affiliations and policy innovations. Historians, too, once embraced the idea that political history was cyclical, and that the nation’s mood swung back and forth from left to right in successive eras.8 As the criticisms of these theories have showed, however, abstract formulations can ignore the contingencies, the messiness, and the unpredictability of history. Relying heavily on data about voter turnout and preferences, such approaches tend to isolate the process of politicking and voting as something separate from the broader tapestry of economic, social, and cultural change. This obscures the intricate and fascinating interrelationship between formal politics and lived experience, between governments and markets, between the rhetoric of the leaders and the actions of the voters.9

The four electoral contests profiled here reveal these rich connections, and underscore the important dynamics of political change that occur in nearly every presidential election cycle. Each of them opens a revealing window not just into their moment in history but into particular aspects of the American political process: its interdependence with economic and social realignment, its distinctive partisan organization, its changing modes of mass communication, and its periodic disruption by particular interests, factions, and third parties.

To be sure, there are many other elections of the past century that served as both hinges of history and windows into a wider landscape of social change. The story of the era’s “pivotal Tuesdays” could cover twenty-five elections just as easily as only four. My point here is not to pick favorites. In fact, I deliberately avoided profiling some of the most familiar races and personalities, for to focus on them alone can keep us in the conventional wisdom comfort zone.

Alone, each of these four races is a terrific story. But by putting them together in one book, we can also see the connective tissue between them and better understand the patterns and continuities of history, as well as the remarkable disruptions and pivot points. They reveal the messiness of the past, the foibles of our leaders, and the fractious, frustrating, two-steps-forward, one-step-back nature of politics and policy. Taken together, the cases also challenge modern notions of what is “left-wing” or “right-wing.” Candidate and party ideologies in this pluralistic, bumptious political system are rarely black or white, but often made up of many shades of gray. The reality is that elections are evolutionary, not revolutionary; they provide clues to bigger changes that have happened, that are underway, that are soon to come.

It’s hardly surprising that presidential contests have received so much attention from scholars and writers, not to mention pundits, policy wonks, Hollywood screenwriters, and pop-culture commentators. Filled with oversized personalities, overheated rhetoric, and unpredictable twists and turns, American presidential campaigns can make for some of the most entertaining kind of history. Yet they are more than just ripping yarns. They are moments that both reflect their times and shape what comes next. They remind us that leadership matters, and that certain individuals have had an outsized effect on the course of national and international affairs. That’s not all. The stories of presidential campaigns remind us that political leaders are one part of a vastly larger picture, and that presidents and would-be presidents are products of their times. Their electoral success and failure depend on a whole host of factors, including ones far out of the candidates’ control.

Elections hinge on whether the nation is in economic boom times or recessions, as well as reflect the shifting social and economic priorities of a country as it moved from being predominantly rural and agricultural to urban and industrial, and then suburban and postindustrial. They hinge on who can vote, who is motivated to vote, and the technologies of communication that influence choices at the ballot box. The advisors, campaign managers, and party organization that surround a candidate can make or break an election. Demographics, economics, culture: all these things make the difference between winning and losing. In turn, the elections and their outcomes can have a profound effect on nearly every other aspect of society.

While these connections were present in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it was in the twentieth century that they truly took center stage. After decades of largely unmemorable chief executives who took a back seat to power brokers in Congress, the twentieth century’s first elected president, Theodore Roosevelt, enlarged the prominence of the office and embarked on a steady expansion of executive branch powers. Roosevelt’s oversized personality helped create a new template for the modern presidency, a role that demanded a leader to be both policy-savvy and paternal, commanding and charismatic, powerful and populist. While the framers of the Constitution had originally envisioned the legislative branch as the instrument of the people’s will, the corruption and ineffectiveness of Gilded Age Congresses made the moment right for the presidency to assume the mantle. The growth of the federal government over the course of the century reinforced the centrality of the White House and its occupants. America’s dominant role in world affairs further propelled the president to the center of popular consciousness. Innovations in communication technology—from radio to television to Internet—continually upped the demand for a president, or presidential candidate, to be persuasive and likeable.10

In the twentieth century, it mattered tremendously who was president, and thus the process of getting presidents elected took on a significance unparalleled in earlier eras. Elections themselves became windows into broader changes. They revealed the remarkable evolution of the two major parties, the campaign process, and the modern presidency. They also revealed shifting currents in the American economy and society, in how people lived, worked, dreamed, and voted.

In the election of 1912, Teddy Roosevelt returned from the political sidelines to run a fiery third-party campaign against Democrat Woodrow Wilson and Roosevelt’s old friend and political disciple William Howard Taft. No third-party candidate before or since has won such a large portion of the vote. Propelled by modern campaign machinery like barnstorming tours and savvy use of the media, the candidates of 1912 sidestepped traditional party organization and brought their appeals directly to voters. The election also laid bare the great tensions and debates generated by the rapid industrialization, urbanization, and immigration of the Gilded Age. The laissez faire approaches of earlier presidencies seemed to be a thing of the past. Now, all parties agreed that something had to be done by the government to regulate and alleviate the inequities of the industrial economy.

The 1932 election unfolded amid the depths of the Great Depression, in a nation where industrial production had plummeted and nearly 25 percent of Americans were out of work. The two major candidates offered voters different solutions to the crisis. President Herbert Hoover argued that government’s role was to encourage business to fix itself, while his challenger Franklin Roosevelt declared that bold government action was the only way to restore prosperity. Voters sided with boldness, and Roosevelt—and his vision of a “New Deal” with the American people—won, fundamentally changing the relationship between citizens and the state. As with nearly every twentieth-century president, Roosevelt won not just because of the substance of his message, but because of the style of his delivery. He used the new medium of radio to deliver powerful, personal messages into voters’ living rooms. His campaign staff used stagecraft as well as tough-minded political strategy to edge out the other Democratic challengers and, ultimately, Hoover himself.

Full of political plot twists, electrifying moments, and unbearable tragedies, the election of 1968 redefined both liberal and conservative politics. It also set the stage for the next four decades of presidential campaigning. An incumbent president chose not to run again, hobbled politically by an escalating and increasingly unwinnable overseas war. Inner-city neighborhoods were in flames, protests rocked college campuses, and assassins’ bullets felled iconic leaders. Television brought all this strife and cultural transformation into American living rooms. The tensions between the political establishment and the youthful counterculture erupted violently at the Democratic convention, helping set up a Republican victory in November by a candidate whose political career seemed finished only a few years before, and laying the foundations for today’s red- and blue-state America.

Ultimately, the story of 1968 doesn’t just explain 1968. It explains what comes afterward. The Democratic Party was a much bigger tent, and much more open to new voices, but it had lost the establishment power it had enjoyed from the New Deal through the Johnson years. Meanwhile, the Republican Party had found a new way to talk to voters, and had made inroads into critical parts of the old Democratic base. Twelve years later, Ronald Reagan’s landslide victory over Democratic incumbent Jimmy Carter was a triumphal execution of the political messages and strategies employed by Richard Nixon in his first White House win.

For all its drama and hype, the 1992 election can be overlooked because it seems to pale in comparison to the earth-shaking contest of Reagan versus Carter, and the cliff-hanging and hotly disputed 2000 race between Al Gore and George W. Bush. Without diminishing those other two critical political moments, the 1992 election rises in significance because of the profound global transformations surrounding it. It was the first presidential race after the end of the Cold War, and the first to feature a candidate born after World War II. It happened at the cusp of the high-technology revolution, and was the first campaign driven by—and perhaps decided by—the all-consuming media environment of cable television.

Riding high after the success of the Gulf War, incumbent George H. W. Bush seemed at first to be a sure bet for reelection, but a souring economy changed the electoral math. After a series of failed Democratic campaigns for the White House in which “liberal” became a dirty word, Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton ran as a centrist “New Democrat,” espousing policies like welfare reform and government efficiency. But the election, and Clinton’s ultimate victory, hinged on the insurgent third-party candidacy of businessman H. Ross Perot, whose campaign reflected the growing power of the independent voter and of communication in the Information Age.

Elections connect to one another. The progressive themes of 1912 echoed on in the campaigns following it, creating a rhetorical and substantive foundation for the debates of 1932. The contest of 1968 revolved around debates and constituencies set in place by Roosevelt’s New Deal, and reflected both the great hopes and crushing disappointments that emerged from the struggles of the 1960s, from civil rights to Vietnam. It also signaled the rise of a powerful new sort of conservatism, born of frustration with social unrest and anxiety about the new racial and economic order, and fueled by the movement of people and jobs from North to South, East to West. The connective tissue stretches across election cycles. While 1968 laid the groundwork for Reagan’s victory in 1980, the Reagan Revolution helped make possible the political rise and electoral triumph of Bill Clinton in 1992.

Three major themes run throughout the chapters that follow. The first is the extraordinary dynamism of the American political spectrum over time. These cases show us that the United States is neither a conservative nor a liberal nation, but one in which political categories and identities are far more messy, multilayered, and difficult to categorize. Politics has a symbiotic relationship to the broader society. The balance between the two ends of the political spectrum and the composition of the debates and temperaments along it change as the economy changes, as culture changes, and as the makeup of the electorate changes. Rather than thinking of American political history as a pendulum swinging between left and right, we should focus on the center, which shifted more incrementally in either a liberal or a conservative direction as times changed. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the center of American politics was several steps to the left of where it landed two decades later, in the eras of Reagan, Bush, and Clinton. Definitions of “liberal” and “conservative” changed over the course of the century, and something considered dangerously radical (or alarmingly conservative) in one generation became centrist in the next.

Successful candidates adapted and responded to these electoral recalibrations. The winners were those who adapted the best to changing times, not necessarily those candidates who first gained traction because they epitomized the new political mood. Teddy Roosevelt brought progressive political ideas to the national stage in 1912, and Woodrow Wilson won partly because he took on some of these ideas as his own. Law-and-order populism propelled the southern segregationist and Democratic candidate George Wallace into the national spotlight in 1968, but Nixon won in part by delivering the same message in less strident and more slickly packaged ways. Reagan led the conservative revolution after 1980; Clinton adapted some of these ideas and words into the platform that brought him victory in 1992.

The second major strand is the continual redefinition of the two major parties through pivotal presidential contests, and the role of third parties in this redefinition. The bedrock constituencies of the Republican and Democratic parties changed profoundly over the course of the twentieth century, as did the issues the two parties championed. At the start of the century, the GOP was the more progressive of the two parties, based in the urban Northeast and advocating a bold government action and promoting the growth of a public bureaucracy. The Democrats were the party of the rural South, of more minimal central government and less federal regulation.

Independent parties and voters also made a difference. In three of these four elections, third-party candidates played a disruptive, even decisive role in the ultimate outcome of the election. Teddy Roosevelt’s run siphoned so many votes from the Republicans that the Democrats won back the White House for the first time in years. George Wallace garnered far fewer votes, but he fractured the Democratic base and introduced populist rhetoric that Republicans later employed to win national victories after decades of Democratic dominance. While H. Ross Perot did not manage to win a single electoral vote, he won the largest share of the popular vote of any third-party candidate since TR, and he forced the other candidates to take new issues seriously. Even when third parties don’t win, they have an indelible effect on how elections play out—and on the two major parties.

The third theme of the book concerns political communication. Over the century, changes in media and communications changed not only the way campaigns were run, but also the relationship between presidential candidates and individual voters. Breaking with the nineteenth-century pattern where candidates gave few speeches and relied on surrogates to hit the road on their behalf, the 1912 election ushered in a new era of candidate-centered campaigning. The rise of national media further fueled a new emphasis on the personalities and charisma of the men who ran for president. By 1932, most American homes had a radio, and this created an opportunity for an even more personal relationship to develop between president and voter. Television was another earthquake on the campaign landscape by 1968, beaming news from around the world into American living rooms and demanding candidates who were telegenic and able to spout snappy sound bites rather than long-winded speeches. By 1992, the 24-hour news cycle propelled by the rise of cable television news not only created a demand for perpetual feeding of the media “beast” but allowed campaigns ample air time to take their messages, and their campaign “spin,” directly to the voters.

All these themes are intertwined and interdependent. Changing modes of political communication contributed to the decline in partisan attachments and helped third-party candidates gain traction. New technologies gave politicians fresh ways to communicate to voters, and an ability to talk to citizens directly without the mediating influence of party organization. At the same time, innovations in the way American elections worked encouraged the widespread adaptation of new media. Late nineteenth-century reforms like the adoption of the secret ballot made more direct means of political communication and persuasion necessary, sowing the seeds of entirely new fields of campaign communications and political advertising. The rise of organized political interest groups in the early decades of the twentieth century helped propel the growth of print media and radio as means of political communication, as different lobbies appealed to voters’ hearts and heads through ever more sophisticated appeals. Successive waves of communication innovation, from radio to television to the Internet, allowed third-party candidates to spread their message and win voter support. More broadly, the rapid expansion of the electorate due to population growth, immigration, and women’s suffrage meant communication needed to be carried out on a scale that was simultaneously mass in its reach and targeted in its messages.11

Ultimately, presidential elections are places where the ordinary and the extraordinary meet. While it is wrong to assert that certain elections “changed everything,” they are nonetheless singular and significant events in the historical landscape, with effects that resonate far beyond the first Tuesday in November. Elections are driven by giant personalities and increasingly complex and expensive campaign organizations, but for all their bluster and spin and hanging chads, they are instruments of democracy. Once every four years on the first Tuesday in November, American voters make their choices, mark their ballots, and determine who wins and who loses. The heat and light of a presidential campaign leaves an indelible mark on all who decide to run, and especially those who win. Even the fiercest political rivals ultimately bond together because of the shared experience of being president.

Once friends, Jefferson and Adams became bitterly divided by the election of 1800. With the passage of time and the mellowing of old age, however, their enmity began to thaw. In 1812, Adams finally reached out to Jefferson, writing a letter to which Jefferson quickly and warmly responded. Adams’s letter, he wrote “carries me back to the times when … we were laborers in the same cause, struggling for what is most valuable to man, his right of self-government.”12 Thus began a lively and affectionate correspondence between the two old rivals that continued until the end of their lives. On hearing of the election of Adams’s son John Quincy to the presidency, Jefferson wrote: “I sincerely congratulate you on the high gratification which the issue of the late election must have afforded you…. So deeply are the principles of order, and of obedience to law impressed on the minds of our citizens generally that I am persuaded there will be as immediate an acquiescence in the will of the majority as if Mr. Adams had been the choice of every man.”13 Elections come and go, Jefferson seemed to say, but the values of democracy endured.

Remarkably, Jefferson and Adams died on the same day: 4 July 1826, the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Politics had consumed most of their lives and torn apart their friendship, but they ultimately found common cause in the democratic ideas that had made them revolutionaries. In the decades that followed, many other giant personalities occupied the office of the presidency. It was not until the turn of a new century, however, that the great debate that had consumed the early republic—big government or small government? a nation of farms or a nation of factories?—took center stage once more in presidential politics.