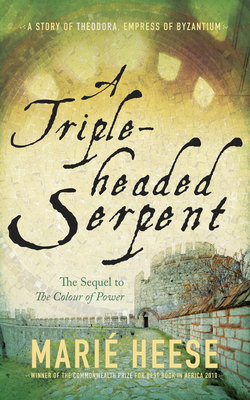

Читать книгу A Triple-headed Serpent - Marié Heese - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Prologue: A visit at dusk

ОглавлениеA chill breeze carried the bitter scent of ash. Still strong enough to mask the salt tang of the sea, it made the solitary pedestrian cough. No wonder, he thought, when almost a third of the city had been set to the torch. Swathed in a heavy woollen cloak with the hood drawn well over his head, he strode along the street, his authoritative boots asserting his right to be where he was. He was tall, and broad with it; armed, of course, with a short sword and a dagger, but he did not anticipate being set upon. Normally he would have been accompanied by an entourage, but his mission this night was one that he wished not to be witnessed.

Around him in the deepening dusk lay the still smoking ruins that now disfigured Constantinople: the Baths of Zeuxippus, the Church of the Holy Wisdom, the Hospice of St Samson, the Church of Eirene, all reduced to blackened rubble. Jagged walls, broken arches, drunken pillars and defaced mosaics were all that remained of the great buildings, sacred and profane, that had been destroyed by the rebellious mob, aided and abetted by a wild wind from the north. Shattered statues littered the street. He stepped nimbly over a cracked head that still maintained a haughty stare with one remaining marble eye.

But all was quiet now, the wind grown tame, the populace gone to earth, some men still nursing wounds and all of them shocked into submission by the radical violence of the two generals and their mercenaries. He had the street to himself. Even the beggars had not yet returned. The only sign of life besides himself was a rat that pattered past and darted into a crevice with a flick of its tail.

He reached an alley between two shops with their fronts boarded up. This was where he had been told to go. Now he stepped more quietly: careful, alert. Reached the third door on the left, a heavy one with iron studs. Yes, this was it. He rapped on it. Stood a while, rocking on his heels. Rapped again, impatiently. Then a couple of bolts rattled, the door swung open and he went in.

“The Kyria is expecting you,” said the servile eunuch who had let him in. “Follow me.” He led the way down a narrow passage to a room warmed by a brazier, scented with incense.

A woman sat at a small round table draped in wine-red velvet, in a pool of light cast by an oil lamp. She sat upright, apparently staring down at her hands clasped in front of her. At first glance she looked young and lovely. A second look showed the first impression to be quite wrong: in fact, she was old, with white hair braided and pinned and thin shoulders draped in a grey shawl. But she had the strong clear bones of a beauty still, covered in almost transparent skin like pale porcelain, finely fissured by time. He stood wordless, made to feel huge and clumsy by her pale delicacy.

She tilted her head up. “Good evening, Sir,” she said in a musical voice. “You should take a seat.”

The eunuch offered a chair opposite hers. The man sat down heavily, throwing back the hood of his cloak to reveal the face of a man accustomed to dominating the company he found himself in. Fleshy lips, firmly clamped; a nose broken at least once, attesting to a violent youth; the broad flat cheekbones of marauding Slavic ancestors who rode the Steppes before coming to rest in a verdant Cappadocian valley; dark eyes with a guarded yet penetrating glare beneath wiry eyebrows.

But she did not react to his striking appearance. Her eyes were milky pearls.

“Evening,” he grunted. He felt out of place. He resented women he could not dominate or use.

“I am Alicia,” she said. “Bring the gentleman some wine.”

The eunuch trotted off.

She sat quietly, waiting.

He coughed. “I am John,” he said. “Known as the Cappadocian.”

She nodded. “A man of considerable energy and power. Capable and ruthless. Huge appetites.”

He chuckled, richly selfsatisfied. “That much anybody could have told you. Doesn’t need extraordinary divining skills.”

She nodded again. “A man of overweening ambition.”

“Fairly obvious.”

“Who never knew a mother’s love.”

He was silent for a few counts. Then: “A lucky guess,” he said.

The eunuch brought wine in a crystal goblet.

“Leave us,” she said. “When I need you, I’ll ring the bell.”

“Yes, Kyria.” He backed out.

“Give me your hand, John,” she said.

He put out a peasant’s hand, broad, with thick fingers and dark hair on the back. She took it in both of hers, fine-boned and cool to the touch. He looked down at her delicate, tapered fingers.

She moved her fingertips across his palm as if reading something there by touch. “Ah. A long life, and an eventful one.”

“Glad to hear it’ll be long,” he said. “First thing you couldn’t have already heard or guessed. But then, who’s to know if you turn out to be wrong?”

“Riches. Yes, great riches.”

“I’m already rich,” he said. “Everybody knows that.”

“And poverty,” she went on. “Dire poverty.”

“Well, I grew up poor,” he said. “Also common knowledge.”

“No, no. Still to come.”

“Poverty? Nonsense. I am very, very well off.”

“You shall be poor again,” she insisted.

“I don’t believe you. I have so much … No, no. Impossible.”

She shrugged.

“What else can you tell me?”

“What is your chief concern?”

He leaned forward eagerly. “The future of … my career?”

She considered, drawing circles on his palm.

“And don’t tell me I have been dismissed from my post. There’s nobody in this city that doesn’t know that.”

“That which has been taken away, shall be restored,” she told him.

He sighed with relief. “When?”

“I cannot say exactly. But probably quite soon.”

He grunted with satisfaction. “The same post? I’ll be Prefect of the East again? In charge of taxes?”

“If you are careful, yes. Wait patiently and do nothing to attract attention.” Her questing fingers pressed more firmly on his palm. “Eventually,” she said, “the mantle of Augustus will fall upon your shoulders.”

He drew in a deep breath. Now, suddenly, he was ready to believe her. “The mantle of Augustus? Are you sure?”

“I read it, here. I tell you truly. The mantle of Augustus.”

“When?”

“I cannot tell exactly when. Eventually.”

“It will take time,” he breathed. “I can wait. And plan. And be ready.”

She continued to stroke his hard hand. “A girl,” she said. “A young girl. Important in your life.”

“My daughter,” he told her. “Only one of any importance.”

She nodded. “She is your weakness. You must beware.”

“Beware? But not of her, surely! She loves me! She is my one ewe lamb!”

“Beware,” she reiterated. “There is danger here, associated with her.”

“I must take care of her,” he said, interpreting the warning in the only way it made sense to him. “People could strike at me through her. It is right that you should make me more aware of this.” He was now completely convinced of the sibyl’s capabilities. “She shall have bodyguards. Well, well. And … anything else of import?”

“You have been a follower of Mithra,” she said, suddenly.

He drew in a deep breath, horrified that she should say this. Paganism was completely forbidden and could cause him to be exiled, if not executed. Certainly it would keep him out of a civil post. “But no longer,” he said quickly.

“No. Now you are a man who knows no god.”

At this he sat mute.

“But one day you will turn to the Christ … This will happen when … the mantle of Augustus falls upon you.”

“Yes,” he agreed. “The Emperor is God’s Vice-regent here on earth. He must be seen to be devoutly Christian. Yes, that makes sense. And? What more?”

She sighed. “I have told you all I am able to divine.”

“You can’t say how … or when … ?”

“I have told you all I can,” she said. “But you have heard what you wanted to hear, no?”

He cleared his throat. “I suppose so. Yes.”

She smiled, a smile still as sweet as it must have been when she was young and comely, revealing rotten teeth. She let go of his hand, turned her two slender hands upward and extended them toward him. He filled them with gold, before stalking off into the night.