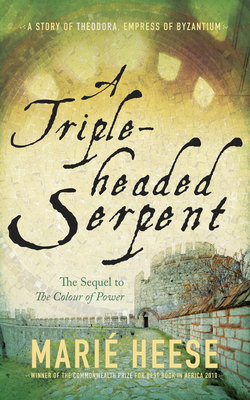

Читать книгу A Triple-headed Serpent - Marié Heese - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Narses the eunuch: his journal, AD 532

No easy thing

Оглавление2 February, AD 532

It is no easy thing, to get rid of an emperor. One who has been chosen by the Senate, supported by the army and proclaimed to the populace. Thrice August. Crowned and consecrated, God’s Vice-regent here on earth. Even when that same populace has varied and deeply felt grievances and wants to get rid of the man they once hailed and revered.

The people of Constantinople now know this fact. The Sanitation Department has removed the corpses, all thirty thousand of them, from the Hippodrome, and the tiers of seats that ran red with blood have been scrubbed with lye. But memories are harder to eradicate. All over the city there are walking reminders of the day they tried to put a different despotes on the throne: men marked with terrible scars or mutilations. But the most grievous reminders are invisible; they are the empty places where once there was a father, a brother or a son, a friend or lover, forever lost when the generals Belisarius and Mundus, with their Goths and Heruls, fell upon the mutinous gathering in the great circus, and cut out the heart of the revolt.

I was there, that day, I saw it all. Disguised as a slave in a tattered cloak, I stood with my back to the wall near the Nekra gate and I watched the slaughter. I saw the blood of thirty thousand men spilled in one day in one place, an urban place, not the kind of ground where battles are usually fought. I saw the blood drip and puddle on wooden stands and marble seats and on the hard earth compacted by thousands of thundering horses’ hooves. I saw the entire Hippodrome painted red. That frightful scene brought a sudden insight to my mind: red, rather than purple, is the true colour of power. Whoever wields absolute power will, sooner or later, have to consolidate it with blood. No matter how noble the autocrat’s ideals, it will inevitably come to this.

I saw, also, framed above the holding pens for racing chariots like a puppet show, the palace guards come rushing into the Kathisma to lay hold of the newly crowned Hypatius and his brother Pompeius and drag them back into the palace through the Ivory Gate, together with their recently assembled entourage. I witnessed the brief reign of the usurper coming to an ignominious end. I remember that I noticed the sun glinting on the ferocious fangs of the triple-headed serpent that tops the tower of Apollo on the spina around which the racing chariots hurl themselves to victory or disaster. The three heads appeared to me to be grinning in mockery.

As the Commander of the Imperial Guard, I oversaw the execution of the brothers as ordered by Justinian, and I stood on the icy shore when their bodies were cast into the sea. I saw the usurper float away into the deep.

I believe that Justinian, left to himself, would have been merciful. But the Empress Theodora, whose stirring words had stiffened the resolve of those who had been suggesting flight, pointed out that the sorry pair would always remain a possible focus for discontents, since they do have royal blood from the late Emperor Anastasius, their uncle; moreover, said Theodora, with characteristic pragmatism and clarity, Hypatius had been crowned. Even such a travesty as it had been, lacking the blessing of the Patriarch and enacted with a borrowed golden chain fashioned into a makeshift diadem – even so, he had been crowned. But the Empire of Byzantium can have only one emperor.

They had to be executed. So they were. And I saw them taken away like flotsam, drifting out to sea on an ebbing tide, the would-be emperor nothing more than food for nibbling fish.

No, no easy task to unseat a reigning emperor. Justinian has reasserted his right to the throne and his power in utterly convincing terms.

And yet he has been weakened. The formerly unthinkable has been thought, and almost turned to deed: there nearly was another emperor. The populace desired another emperor. So did the great landowners and the nobility, who have never truly accepted a peasant and a former actress and courtesan on the throne. Everybody has considered this possibility: there could be another emperor.

Perhaps this end may yet be striven for, though possibly by other means.

We must be vigilant.