Читать книгу Babaji - Message from the Himalayas - Maria-Gabriele Wosien - Страница 5

I SADASHIVA AVATAR 1) ENCOUNTER

ОглавлениеBhole Baba ki jai! ..... Bhole Baba ki jai! ..... Bhole Baba ki jai! These shouts of joy can be heard from the direction of the river ..... becoming more and more distinct now. In a few minutes Babaji will come into view as the thick line of bushes along the dusty village track turns wispy and comes to an end. Every afternoon, after bathing in the river, he returns to the temple on the hill, always pursued by a motley group of people - a mixture of devotees, curious onlookers and a straggle of children.

It is about five o'clock. The intense heat of the day has passed and it feels good to be outside again, beyond the dormitory'; cool and shady shelter so eagerly sought a few hours ago. I feel refreshed after taking a bath in the pleasant late afternoon sunshine and relieved that it's over and done with, happy at the sight of the washing completed - metres and metres of colourful, dripping wet saris and other garments hanging out on a line strung between two trees near our room.

Accustomed to the mod cons of western urban life, I have been finding it difficult to adapt to the 'simple' ways of an Indian village. I hadn't even known such ways existed! For instance, I've only just figured out how to bathe in public while fully dressed - well practically anyhow. It's' far easier on a moonless night when we take the morning bath. The twice daily bathing ritual, before sunrise and at sunset, is a sacred duty for every religious Indian.

My attempt goes something like this: unravel the sari and let it fall to the ground; hitch up the half-petticoat to the underarms and secure it tightly; remove the sari blouse; if lucky enough to have found a rare bucket at this hour, lower it slowly, slowly into the deep well and take care to keep my balance. The well's familiar inhabitant, a giant tortoise, nimbly dodges the shakily descending bucket, and then there's the job of heaving up the pailful of precious water.

By now a wide-eyed audience - several village women and a horde of children of all ages - has come out of nowhere to witness the rare spectacle of how a white memsahib tries to have her wash. My soap is the subject of much attention. The other day I had observed from a respectful distance how some Indian women at the riverside were rubbing each other down with pumice stones. Now squealing and shrieking and waving their arms about in excitement, they move in on me so closely, having a very different sense of personal space, and leave me no room to manoeuvre!

Next to pour the water in cupfuls over my body and try, despite intense public scrutiny, to arrange the dry clean clothes over the sopping wet petticoat and against the friction of wet skin. Meanwhile the uneven ground beneath me has become very slippery, so now there is the added tension of performing a balancing act to avoid a likely mud bath.

When the ordeal is finally over, I grab the bucket and laundry and make a speedy getaway from my rapt audience through a hole in the back fence of the ashram. There is one more obstacle - to climb over the pile of leaf-plates which get thrown over the fence after the midday meal and which by now have been thoroughly licked clean by all the stray dogs.

I had just finished hanging up the washing when the signal for Babaji's return was sounded.

As if magnetised, the devotees start running excitedly from all corners of the ashram towards the main entrance gates or further down the path and stand in joyful anticipation. Everyone wants to be the first to touch the beloved one's feet or at least the hem of his garment - in any case, a chance to get dose to him. Babaji is now stepping onto the narrow plank placed across a ditch full of running water skirting the outer wall of the temple. Soon he passes under the archway decorated with palm fronds, flowers and sacred symbols. A couple of flower garlands are reverently and deftly placed around his neck.

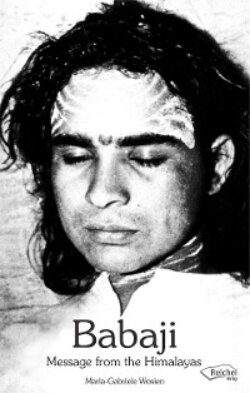

For many people newly arrived today, it is their first sighting of the legendary saint and avatar [divine incarnation]: his presence makes him seem taller than he really is; his face with its fine features is youthful and appealing and shines with pure radiance; you cannot miss his sparkling eyes with their seemingly casual but deeply penetrating focus; and around the corners of his lips lurks a playful smile.

Some young mischief-makers have managed to crawl between his legs. He suddenly assumes a mock-fierce grimace and brandishes his stick and so gets them speedily scurrying off. With the pathway now partially cleared, his walk changes into a sprint, creating a moving picture of sheer lightness and gracefulness enfolded in the flying colours of his robes. In no time he has reached the dais, specially erected for him under the brightly-hued marquee. All the others have yet to catch up.

Alighting on his asana, he throws back his head and laughs gleefully, like a child. The young ones finally catch up, squealing with delight but Babaji's face has already adopted a serious, almost dark expression. He tells someone standing beside him to bring the crowd to silent order. The people quickly move in and squat down, men to one side, women to the other, leaving an aisle down the middle.

Again Babaji is on his feet, running down the aisle gathering all the children with the aid of his stick and sweeping them towards the back of the tent. Soon he has them sitting in orderly rows and begins an improvised lesson: "Om namaha Shivaya. Om na - ma - ha Shi - va - ya. Om na - ....." ['I surrender to God; Thy will be done, O Lord']. Babaji takes care that the syllables are pronounced correctly. In high-pitched eager voices the chorus begins to repeat the prayer and the initial gabble soon becomes dear and rhythmic. Before long the cheeky little brats become amazingly transformed.

Awe-inspired and timid, they gaze up with huge eyes at the formidable radiant figure standing before them, staff in hand, resembling an angel of the Lord. It brings to mind Rafael's painting of the angels sitting at the feet of the Sistine Madonna. The lesson lasts about ten minutes and Babaji returns to his seat.

Meanwhile a long queue of devotees, some of whom have come from distant parts, has formed to pay their respects to the saint from the Himalayas and to offer him gifts. Each one in turn bows down or kneels and touches his feet, places the gift beside him and then humbly moves away. The devotion and reverence with which these people approach the adored master is deeply moving to watch. Some come with a request for advice or assistance, but to all Babaji bestows blessing, sometimes raising his right hand or lightly placing it on the person's head and inclining towards him or her in a kindly way.

The offerings of fruits and garlands of flowers are by now piling up on the dais and Babaji has them distributed to all the people present. Through his touch these gifts have become imbued with divine grace and blessing and are therefore regarded as something very precious. Sometimes, especially when Babaji tosses pieces of fruit and sweets,to the crowd, a jolly scuffle ensues as to who will catch the prasad [blessed food]. There are always many more hands than projectile gifts, yet this game is particularly enjoyed by the people.

"What kind of saint is this supposed to be who behaves so frivolously inside the temple precinct?" asked a disgusted villager earlier this morning.

"He is Bhole Baba", a devotee ventured to explain, "he is the Lord whose nature is simplicity - bhola, like a child."

There are precisely 1008 names, or masks, or aspects by which God is known and Bhole Nat]; the Lord of Simplicity, is but one of his manifestations. His childlike behaviour makes him approachable yet it masks the unfathomable seriousness of his Being. Kashi Vishwanath Bhagwan is the title his disciples use when paying homage to him. Kashi is the classical name of Benares, the sacred city of the Hindus and seat of the main Shiva temple; Vishwanath Bhagwan means 'Lord of the Universe' and refers to his pure divine nature.

It gets dark suddenly, the little coloured lights are turned on and the accumulated pile of flower garlands is removed and used to decorate the dais and the rest are laced around the tent poles. Babaji retires for a short while to his kuti [little room].

In the temple area the crowds are getting thicker as more and more devotees and spectators arrive for the evening arati - the offering of lights, soon to begin. Chanting is already filling the room, particularly the intoning of the mantra Om namaha Shivaya to the accompaniment of a harmonium, various drums and cymbals. Between chants a babble of murmuring voices can be heard instead and the ones who have recently arrived take the opportunity to push through and step over (on!) everyone to join their friends and relatives sitting in the coveted front rows; someone is passing a screaming baby over my head to its mother and with all the jostling I am shaken out of a brief and peaceful contemplative state.

Quiet once more. Babaji has come and is seated on the asana, cross-legged, hands resting on his knees, head inclined slightly forward, eyes lowered. The arati begins.

This divine worship at sunrise and sunset is the most sacred part of the day. To the chosen form of divinity, whether it be a picture, a statue, or the avatar himself, are offered incense, flowers, fire and water to the accompaniment of sacred chants and ritual gestures. Fire is the symbol of the sun - a life-giving divinity - it is the power that purifies and its perfection reflects the enlightened one. Water is offered as the elixir of life.

The arati to Babaji himself is a time when one can catch a glimpse of his essential transcendent quality. Today, dressed in white, it seems as though his body is no longer touching the seat, his frame appears nonphysical, almost a part of the stillness that emanates from him. His eyes are wide open now and gaze calmly into the sacrificial fire; it is as though his body has become translucent, letting through the light which is the very nature of his being. I turn and look into the faces of those sitting near me; all of them are etched with weathered lines born of a hard life, yet the sincerity of these people's devotion imparts such a softness to their features and the same light shines through their eyes also. I cannot remember ever having witnessed a more moving ceremony than this celebration of the mystery of light.

The evening arati ceremony is followed by an improvised programme of chanting, the opportunity of darshan and a couple of brief addresses given by devotees to the assembled group. Little by little the evening's events take on the atmosphere of a folk festival - the bright decorations blend well with the colourful character of all the goings on, the 'theatre', fitting the maxim: 'no colours, no guru'. Eventually Babaji stands up and makes his way down the aisle to leave and retire for the night. The crowd quickly disperses and soon there is only silence and darkness.

An odd little group or two remains quietly holding satsang [sharing of spiritual experiences]. Some brahmins have gathered round the yagna-shala where tomorrow the traditional fire ritual, which has been performed daily over the last few days, will reach its climactic end. After that a bhandara [great feast] will be held and the whole village is invited. Out on the wide terrace one disciple is attempting to explain to a newcomer the historical background of the phenomenon of Babaji as avatar.

All else is very still now. The sky is so vast and starry in this place and amplifies the peace of the blackened landscape. Some more shrouded figures join the disciple on the terrace and squat down to hear his stories in the dim light of a little oil lamp. I too go softly over to them and listen.