Читать книгу Dispossessed Lives - Marisa J. Fuentes - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

Rachael and Joanna: Power, Historical Figuring, and Troubling Freedom

Scandal and excess inundate the archive … The libidinal investment in violence is everywhere apparent in the documents, statements, and institutions that decide our knowledge of the past.

—Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts”

[H]istory reveals itself only through the production of specific narratives. What matters most are the process and conditions of such narratives…. Only through that overlap can we discover the differential exercise of power that makes some narratives possible and silences others.

—Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past

Item it is my Will, and I do hereby manumit and set free my negro Woman named Joannah from all Servitude whatsoever, and for compleating that purpose I do hereby desire my Executors herein after named to pay all such Sums of money and Execute such deeds as are necessary about the same:—And I do give, devise and bequeath unto the said woman Joannah, her child Richard, and a negro Woman named Amber, with her future Issue and Increase, to her the said Joannah and her heirs forever.

—Will of Rachael Pringle Polgreen, 1791

The great hurricane of 1780 destroyed lives, homes, and businesses, and free people of color felt acutely the tenuous nature of their freedom in Bridgetown. On 20 July 1793, Captain Henry Carter and William Willoughby—two white men—swore under oath that Joanna Polgreen, “a certain negroe or mulatto woman,” had been freed in 1780 but had lost her manumission papers in the storm.1 Carter and Willoughby testified that Joanna was once owned by Bridgetown hotelier Rachael Pringle Polgreen, but Rachael sold her to a soldier named Joseph Haycock who promptly freed her from slavery. After her successful reclamation of her freedom Joanna enters another document into the archive, this time a deed wherein she frees her son Richard Braithwaite, “for the natural love & affection which She hath to [him].”2

Joanna’s quest for freedom for herself and her son involved a long journey from slavery in a brothel to freedom and back, and has until recently remained in the shadows of Rachael Pringle Polgreen’s sensational narrative of infamy and fortune.3 Drawing Joanna’s story from underneath Pringle Polgreen’s dominance as a historical agent allows us to reconsider the terms of agency and sexuality in this slave society. We also gain insight into the dynamics between women of color and enslaved women in the context of a sexual economy in an urban slave society. Deconstructing Pringle Polgreen’s historical narrative ultimately exposes the power of certain narratives to obscure the politics of representing success, the violence fundamental to slavery, and the lives relegated to historical anonymity. The challenge, then, is to track power in the production of Pringle Polgreen’s history while recognizing that her historical visibility is also an erasure of the lives of those she enslaved. Doing so reveals, for the first time, the story of Joanna’s struggle and determination in freedom and the limits of freedom, sexual commerce, and agency in eighteenth-century Bridgetown.

Rachael Pringle Polgreen, Historicity, and Liminality

It may be precisely due to Rachael Pringle Polgreen’s “exorbitant circumstances”4 during her life as a free(d) woman of color in late eighteenth-century Bridgetown that historical narratives about her life have not changed since she appeared in J. W. Orderson’s 1842 novel, Creoleana.5 Apart from an important critique by Melanie Newton of the political and historical context of Orderson’s novel, Polgreen’s life story—her triumphs, extraordinary relationships, and visual depictions—has not altered since the nineteenth century. Thus both the archive and secondary historical accounts beg reexamination.

Polgreen was a woman of color, a former slave turned slave owner, and many stories circulate that she ran a well-known brothel without much controversy.6 Persistent representations of Polgreen’s life draw from an archive unusual for women of color in eighteenth-century slave societies. She left a will, and her estate was inventoried by white men on her death—a process used primarily by the society’s wealthier (white) citizens. Her relationships with elite white men and the British Royal Navy are well documented in newspaper accounts and, most significantly, in the nineteenth-century novel by a Bridgetown resident who was likely well acquainted with Polgreen. In the 1770s and 1780s, this female entrepreneur appears in Bridgetown’s tax records as a propertied resident, and her advertisements in a local newspaper allude to the importance she placed on property. From a caricatured 1796 lithograph to the folkloric accounts of Prince William Henry’s (King William Henry IV’s) rampage through her brothel, Polgreen’s story has in many ways been rendered impermeable, difficult to revise, and overdetermined by the language and power of the archive.

Yet the archive conceals, distorts, and silences as much as it reveals. In Creoleana, a “complete” dramatized life story of Polgreen is narrated; it provides a tantalizing but fictional solution to gaps and uncertainties for scholars who struggle with the fragmented and fraught records of female enslavement marked by the embedded silences, commodified representations of bodies, and epistemic violence. However, for Polgreen, it is perhaps her hypervisibility in images and stories that continues to obscure her everyday life, even when the archive appears to substantiate certain aspects of that life. Such powerful narratives, visual reproductions, and archival assumptions erase the crucial complexities of her personhood and obfuscate the violent and violating relationships she maintained with other women of color in Bridgetown’s slave society.

In the scholarship of slavery and slave societies of the Caribbean, Polgreen and other free(d) women of color are centered in narratives about business acumen and entrepreneurship. Several historians discuss the significant role prostitution played in the local and transnational market economy.7 Indeed, in many eighteenth-century Caribbean and metropolitan Atlantic port cities prostitution was rampant and served a significant mobile military population as well as providing local “entertainment.” During the 1790s, “the symbol of non-white business success in Barbados was the female hotelier.”8 A number of free(d) women found slave-owning and prostitution economically viable routes to self-sustenance, since they and other free(d) people of color were systemically excluded from most occupations and opportunities.9 Bridgetown’s white female (mostly slave-owning) majority, however, tended to own more women than men and set the precedent for selling and renting out enslaved women for sexual purposes.10 Moreover, without the possibility of employing their enslaved laborers in agricultural pursuits, urban white women profited from the surplus of domestic workers by hiring them out to island visitors.11 It is in this environment of slaves, sailors, Royal Navy officers, and other maritime traffic in Bridgetown’s bustling port that Rachael Pringle Polgreen made her living.

However Polgreen’s seductive narrative too often eclipses and silences the experiences of other enslaved and free(d) women who lived during her time. This chapter revisits her story to analyze how material and discursive power moves through the archive in the historical production of subaltern women.12 Reexamining the documentary traces of Polgreen’s life and death illuminates several contradictions and historical paradoxes that make it problematic to characterize Polgreen or enslaved and free(d) women’s sexual relations with white men as unmediated examples of black female agency. How does one write a narrative of enslaved “prostitution”? What language should we use to describe this economy of forced sexual labor? How do we write against historical scholarship, which too often relies on the discourses of will, agency, choice, and volunteerism that reproduce a troubling archive, one that cements enslaved and free(d) women of color in representations of “their willingness to become mistresses of white men”?13 If “freedom” meant being free from bondage but not from social, economic, and political degradation, what did it mean to survive under such conditions?

In the 1770s and 1780s, Bridgetown’s free population of color remained relatively small, but it experienced significant growth by the turn of the nineteenth century.14 This group of “free colored” women and men survived through store-keeping, huckstering, ship-building, prostitution, and a small range of other trades. The Royal Navy’s military infrastructure perpetuated the demand for an informal sexual economy that was not fully met by the efforts of white slave owners in Bridgetown. For former slaves like Polgreen, who had certainly witnessed white owners profiting from sexual violations of black women, it was possible to imagine hiring enslaved women out for similar purposes. And, if it is true that Polgreen’s original owner was her own father, then the sexual dynamics of her life and her business become even more complex.15 Women comprised a majority of slave owners in Bridgetown, some of them women of color. Therefore, female slave owners like Polgreen comprised an important part of the urban landscape. However, Polgreen’s business of brothel keeping diverged sharply from the public economic pursuits of most white female slave owners. Although many white women engaged in “hiring-out” their female slaves for sexual purposes, there is no evidence suggesting that they engaged in running houses of prostitution in Bridgetown.16 While Polgreen’s ability to accumulate wealth was comparable to that of her white counterparts, her avenues for profit restricted her to an arena that would likely have been shameful and disreputable for them.

For studies focused on Barbados specifically, Jerome Handler’s two publications, The Unappropriated People: Freedman in the Slave Society of Barbados (1974), and “Joseph Rachell and Rachael Pringle-Polgreen: Petty Entrepreneurs” (1981), laid the foundation for later discussions of Rachael Pringle Polgreen, free(d) women of color and prostitution.17 Handler’s discussion recounts Polgreen’s enslavement by William Lauder and her freedom and rise to “business” woman—a story drawn directly from the nineteenth-century novel Creoleana. Understandably, subsequent historical work has drawn extensively on Handler’s authority on Polgreen and free(d) people of color in Barbados.18 Consequently, several texts mention Polgreen’s property accumulation, her relationships with white male elites, her shrewd business management, and her demurring yet assertive challenge to the prince of Britain.19 One historian of Barbados contends that property ownership by free(d) women of color, “managed [to] challenge the economic hegemony of whites.”20

Polgreen was part of a “colored elite” who owned property—including slaves—and were able to maintain a standard of living comparable to their white counterparts. But focusing on economic prosperity alone obscures the coercive nature of the enterprise of enslaved prostitution. When concentrated on the economic possibilities for enslaved and free(d) women of color, it is easy to equate black female agency with sexuality without critically examining some of the violating attributes of this labor. Discussions of black women, free(d) or enslaved, using white men as an avenue to freedom often erase the reality of coercion and violence, and the complicated place of black women in this system of domination. Indeed, attention only to opportunities for material benefit suggests that women of color wielded an inordinate amount of power in these sexual encounters. How then, do we tease out the ways narratives of “resistance,” “sexual power,” and “will” shape our understanding of female slavery? Is will, as Hartman asks, “an overextended approximation of the agency of the dispossessed subject/object of property or perhaps simply unrecognizable in a context in which agency and intentionality are inseparable from the threat of punishment?”21 The power gained from slave ownership and enslaved prostitution benefited slave owners while leaving enslaved women in a position in which they could not refuse this work. Polgreen herself was dependent on this system of exploitation that left few other avenues for economic prosperity. This reality, and the archive that documented these circumstances, shaped the way her history has been written, leaving the lives of the vast majority of exploited enslaved women virtually invisible.

Michel-Rolph Trouillot writes of historical power, arguing that history represents both the past (facts and archival materials) and the stories told about the past (narratives).22 Polgreen’s archival remains and the histories written about her clearly represent this interaction between the processes of historical production and her limited power of self-representation, as well as the ways authors who narrated her life represent her agency through her material success. Throughout her life and afterlife, Polgreen served the agendas of divergent political discourses. In the nineteenth century, she was used as a motif to remind white society that black women’s sexuality must be contained; for the postcolonial Barbados elite, she exemplified loyalty to Britain, accommodation, and peaceful negotiation. In more recent scholarship dating to the 1980s, Polgreen and women of color represented successful challenges to colonial domination.

The documents and processes used to fashion “truths” about Polgreen’s experiences represent material accumulation as a triumph over adversity. Polgreen’s inner self—her fears and confidences—remain impossible to retrieve using documents produced in a slave society limited by capitalist and elite perspectives.23 A critical reengagement with the sources elucidates the complexities and contradictions she embodied. Although no birth record survives, historians contend that Rachael Pringle Polgreen was born Rachael Lauder sometime around 1753.24 Her burial was recorded on 23 July 1791 at the Parish Church of St. Michael.25 At her death, her estate was worth “Two Thousand nine hundred & thirty Six pounds nine Shillings four pence half penny,” an amount comparable to a moderately wealthy white person living at the same time.26 According to her inventory, along with ample material wealth in the form of houses, furniture, and household sundries, Polgreen owned thirty-eight enslaved people: fifteen men and boys and twenty-three women and girls.27 In her will she freed a Negro woman named Joanna and bequeathed to her an enslaved Negro woman named Amber. Joanna was also given her own son Richard, who was still enslaved. Polgreen also freed a “mulatto” woman named Princess and four “mulatto” children (not listed in familial relation to any “parents”). Polgreen ordered that the rest of her estate—including William, Dickey, Rachael, Teresa, Dido Beckey, Pickett, Jack Thomas, Betsey, Cesar, a boy named Peter, and nineteen other enslaved people—be divided among William Firebrace and his female relatives, William Stevens, and Captain Thomas Pringle, all white people with whom she had social ties. This bequest—giving away the enslaved as property—was to them and “their heirs forever.”28

The above information survives precisely because of the value placed on property. Produced through her material wealth, Polgreen’s archival visibility relies on the logic of white colonial patriarchal and capitalist functions, reproducing the terms of the system of enslavement. Her burial in the yard of the Anglican Church of Saint Michael’s Parish did not, as a triumphal narrative might argue, exemplify transcendence over racial and gendered systems of domination. Rather, it illustrates the power of her social connections, without which permission for a church burial would not have been granted. We may speculate that the limited degree of Polgreen’s integration into the white Anglican religious community of Bridgetown granted her unusual status given her profession as a brothel owner, even as we acknowledge that her participation in, even acceptance of, the economic and social circles of white slave owners granted her unusual power.

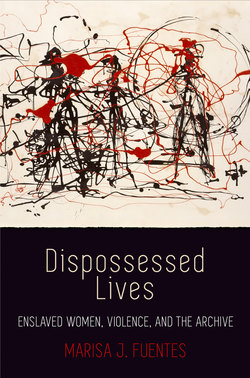

Beyond her will and estate inventory, another remarkable document has survived: a lithograph produced by British artist Thomas Rowlandson and printed in 1796.29 It pictures a large and dark-skinned Rachael Pringle Polgreen seated in front of a house purported to be her “hotel.” Her breasts are revealed through a low-cut dress as she sits open-legged and bejeweled. In the background of the lithograph are three other figures, a young woman and two white men. The young woman is similarly dressed, with a bodice cut even lower than Polgreen’s. She stares, almost sullen-faced, at a large white man appearing in the rear of the picture in a tattered jacket and hat.30 Observing the young woman from the right side of the picture is a younger white man wearing a British military uniform. He is a partial figure, shown in profile only. A sign posted behind Polgreen reads: “Pawpaw Sweetmeats & Pickles of all Sorts by Rachel PP.”31

In 1958, an anonymous editorial preceded the first “scholarly” article about Polgreen in the Journal of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society. The editorial reads the image as a narrative about her life, contending that “a gifted [caricaturist] such as Rowlandson would not … have placed as a background to the central figure of Polgreen in her later and prosperous years characters such as “a tall girl in a white frock,” etc. and an officer looking through a window, which had no relation to her or to her career.”32 In the writer’s view, the figures in the background represent a young Polgreen, averting the repulsive advances of her master/father. The young military man represents her “savior” Captain Pringle, the man credited with granting her freedom. Deduced from the most pervasive narrative about her life, Polgreen’s name came from Pringle after the captain who allegedly purchased her from her father/master William Lauder (d. 1771). After settling Polgreen in a house in Bridgetown, Pringle left the island to pursue his military career, and in his absence Rachael Pringle added the name Polgreen.33

Figure 6. Illustration by Thomas Rowlandson, published by William Holland (London, 1796). Courtesy of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society.

The editorial does not, however, consider the explicit sexual tone of the sign posted above Polgreen. “Pawpaw, Sweetmeats & Pickles of all Sorts” advertised more than the culinary items available for purchase. Free(d) and enslaved women in towns played a significant role in the informal market economy, selling a variety of ground provisions to locals and incoming ships, and the sign above Polgreen clearly situates her within a well-established economic system. She can easily assume the part of a market woman seated outside her “shop.”34 However, the artist’s phallic references on the sign also allude to sexual services offered. The language of “sweetmeats and pickles” worked to both mask and advertise the sexually overt activities within the tavern. At the same time, the image reinforces the positionality of enslaved black women as sexually available, consenting, consumable, and disposable. Many of Rowlandson’s works depict London and other maritime scenes and are filled with sexual references. These include sailors and prostitutes in various sexual acts and stages of undress. It may not be surprising, then, to find him dedicating an entire collection to what was then described as “erotic” art.35 Rowlandson’s caricature of Rachael Pringle Polgreen depicts an extravagant woman of color in various stages of her life. In this single frame, she is racialized, discursively and visually sexualized, and carried across her life-span from a younger, lighter self to an older, darker, larger self. This visual production intertwines Polgreen’s race, gender, and sexuality with a complete narrative of her life story as the artist imagined it. The material fragments of Polgreen’s existence evident in her will, inventory and the lithograph exemplify Trouillot’s concept of archival power.36 Operating on two levels, it influences what it is possible to know or not to know about her life. In the first instance, power is present in the making of the archival fragments during her lifetime. Her will, recorded by a white male contemporary, only leaves evidence of what was valued in Polgreen’s time—the material worth of her assets in property. She left no diary or self-produced records.37 Second, illustrated by the lithographic representation, Polgreen’s image and life history were imagined by a British man whose own socioeconomic and racial reality limited and informed what he produced about a woman of African descent.

In 1842, nearly fifty-one years after Polgreen’s death, Creoleana, or Social and Domestic Scenes and Incidents in Barbados in the Days of Yore, written by J. W. Orderson, was published in London. Orderson was born in Barbados in 1767 and grew up in Bridgetown. His father John Orderson owned the Barbados Mercury, a local newspaper, and J. W. became its sole proprietor in 1795.38 Thus, he would have been a teenager when many of the events he wrote about in Creoleana occurred, although he wrote about them when he was seventy-five. It was likely, as evidenced in the numerous newspaper advertisements Polgreen placed in his paper, that J. W. Orderson knew the female hotelier.39 It is important to read Creoleana as a “sentimental” novel of its time, for the historical context in and the literary conventions with which the novel was written are as pertinent as Orderson’s characterization of Polgreen. The novel was, as Newton suggests, both “a revision of slavery and a moral reformist tale to guide behavior in post-emancipation society.”40 Slavery and apprenticeship had officially been abolished in Britain’s Caribbean colonies by 1842, only four years prior to the novel’s publication. Orderson was clear about his nostalgia for a time in which the enslaved were “happier” in their bondage than in freedom.41 The consequences for Polgreen’s historical reproduction are clear, as Melanie Newton notes in her critical reading of the novel:

In the post-slavery era, as had been the case during slavery, stereotyped and sexualized representations of women of color, especially the “mulatto” woman, often served as the means through which white reactionaries expressed both anti-black sentiment and fear of racial “amalgamation.”42

Acknowledging the pro-slavery project constituent to such representations raises questions about how to use a text like Creoleana as a primary source for Polgreen’s historical “reality.” This is not to dismiss entirely the novel’s potential to historically inform readers or scholars, but rather to offer insight into its distorting representations of Polgreen. At the moment when the British and North American anti-slavery movements were storming across the Atlantic and into the Caribbean, Orderson articulated his pro-slavery beliefs while condemning the “perversion” of inter-racial sex.43 In a pamphlet published in 1816, Orderson responded to British Parliamentary debates concerning the illicit international trade in Africans and the gradual abolition of slavery in their colonies, but his remarks center specifically on the growth of the free population of color in Bridgetown. Using less symbolic language than the novel to describe his abhorrence of inter-racial sex and unions, Orderson explicitly expressed his opinions guided by his own “moral” ideologies. Beyond even his disapprobation for the public display of interracial coupling between military men and women of color, he remarks on the moral decline of white society through this “licentious intercourse” with women of color: