Читать книгу Dispossessed Lives - Marisa J. Fuentes - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Dispossessed Lives constructs historical accounts of urban Caribbean slavery from the positions and perspectives of enslaved women within the traditional archive.1 It does so by engaging archival sources with black feminist epistemologies, critical studies of archival power and form, and historiographical debates in slavery studies on agency and resistance. To trace the distortions of enslaved women’s lives inherent in the archive, this book raises questions about the nature of history and the difficulties in narrating ephemeral archival presences by dwelling on the fragmentary, disfigured bodies of enslaved women. How do we narrate the fleeting glimpses of enslaved subjects in the archives and meet the disciplinary demands of history that requires us to construct unbiased accounts from these very documents? How do we construct a coherent historical accounting out of that which defies coherence and representability? How do we critically confront or reproduce these accounts to open up possibilities for historicizing, mourning, remembering, and listening to the condition of enslaved women?

This study probes the constructions of race, gender, and sexuality, the machinations of archival power, and the complexities of “agency” in the lives of enslaved and free(d) women in colonial Bridgetown, Barbados. A micro-history of urban Caribbean slavery, it explores the significance of an urban slave society that was numerically dominated by women, white and black. By the turn of the eighteenth century, Barbados sustained an enslaved female majority whose reproduction rates contributed to a natural increase in the slave population by 1800.2 Similarly, white women made up a slight majority of the island’s white population and owned predominately female slaves who, in turn, allowed white women a measure of economic independence.3 This unusual demography and the underexplored, intra-gendered relationships between different groups of women mark an important shift from the extant scholarly focus on white men’s domination of black and brown women in slave societies.

Despite its small size in relation to other Caribbean islands, an examination of Barbados, and in particular Bridgetown, enhances our understanding of how race, gender, and sexuality were formed in British Atlantic slave societies and how these constructions of identity directed and influenced the life experiences of urban enslaved women. Unlike similar works on enslaved women of the antebellum U.S. South that draw on the limited voices of the enslaved, this book does not feature sources written by enslaved people themselves.4 On the contrary, the very nature of slavery in the eighteenth-century Caribbean made enslaved life fleeting and rendered access to literacy nearly impossible. Yet the women who appear in the archival fragments on which this book draws offer a crucial glimpse into lives lived under the domination of slavery—lives that were just as important as those of more visible and literate people in this period, who most consistently left an abundance of documentary material. Throughout this work I interrogate the quotidian lives of enslaved women in Bridgetown and account for the conditions in which they emerge from the archives. This is done to bring attention to the challenges enslaved women faced and the continued effects of white colonial power that constrain and control what can be known about these women in the archive. Instead of a social history of enslaved life in Bridgetown and Barbados, I examine archival fragments in order to understand how these documents shape the meaning produced about them in their own time and our current historical practices. In other words, this is a methodological and ethical project that seeks to examine the archive and historical production on multiple levels to destabilize the British colonial discourse invested in enslaved women as property. The impetus to “recover” knowledge about how enslaved women made meaning from their lives is an important aspect of the historiography of Caribbean slavery. A significant amount of historical scholarship now exists showing how these women enacted their personhood despite their experiences of dehumanization and commodification.5 This book builds on that scholarship; indeed, it has allowed me to ask a different set of questions concerning the body of the archive, the enslaved body in the archive, and the materiality of the enslaved body. This work seeks to understand the production of “personhood” in the context of Bridgetown and this British Caribbean archive, while troubling the political project of agency.6 It articulates the forces of power that bore down on enslaved women, who sometimes survived in ways not typically heroic, and who sometimes succumbed to the violence inflicted on them. Each chapter examines one woman in the context of eighteenth-century Bridgetown as she came into archival view. The chapters are titled after the women who are named in the fragments I explore when possible, in order to contest their fragmentation and to challenge the impetus of colonial authorities to objectify enslaved people in the records by generic namings such as “Negro” or “slave.”

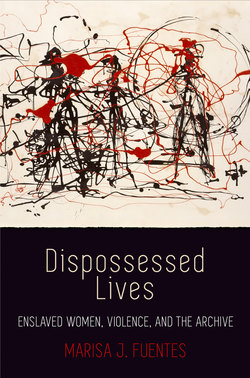

Figure 1. Prospect of Bridgetown in Barbados, by Samuel Copen (London, 1695). Courtesy of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society.

Dispossessed Lives sets out to answer several questions pertaining to enslaved women in the urban Caribbean. How did these women negotiate physical and sexual violence, colonial power, and the demands of their female owners in the eighteenth century? In what ways did urban enslavement differ from the plantation complex? How was freedom defined in this slave society? How did architectures and symbols of terror—such as the Cage that held runaway slaves, and the execution gallows—shape how enslaved women were confined and controlled in an urban context? And finally, what do the archival fragments describing enslaved women alternately uncover and refuse to reveal about their racial, gendered, and sexual experiences as enslaved subjects?

In answering these questions this book thematically illustrates the connections between gender, urban space, and enslavement. Chapter 1 follows an enslaved runaway named Jane through the streets of Bridgetown revealing the precarity of fugitive bodies in urban areas and within colonial discourses in runaway advertisements. Chapters 2 and 3 concentrate on the production of enslaved female “sexuality” dialectically connected to white female identities and enslaved prostitution. These issues are addressed by revisiting the archives of a free(d) mulatto brothel owner and in chapter 3, closely reading an elite white adulteress’s deposition about her sexual affair. In Chapter 4, Molly, an enslaved woman executed for allegedly attempting to poison a white man, characterizes the construction of enslaved (female) criminality and the empty terms of “guilt” and “innocence” in the Barbados legal system governing slavery, which denied the enslaved the ability to testify in any courts. Executions of the enslaved map the functions of physical urban spaces in rituals of colonial punishments, and the power colonial authorities mobilized to invade enslaved afterlives. Finally, in Chapter 5, I bring attention to the “excessive” images of violence on enslaved female bodies that emerge in the debates to abolish the slave trade and contemplate the aurality of pain as a way to consider the rhetorical demands of otherwise anonymous historical subjects.

Over two decades of scholarship on the social histories of gender and slavery and theoretical work on the politics of the archive serve as the foundation for this book’s emphasis on historical production and the archives of enslaved women in Caribbean slavery. These social histories of enslaved women’s everyday lives allow me to focus specific attention on the questions of archival fragmentation and historicity without reproducing their labors on the historical, social, and economic circumstances of slavery in the Atlantic world.7 Driven by questions of historical production in the context of archives that are partial, incomplete, and structured by privileges of class, race, and gender, my work follows the path-breaking scholarship of Deborah Gray White, Jennifer Morgan, Camilla Townsend, and Natalie Zemon Davis, who found ingenious ways to use known biases within particular archives to ask seemingly impossible questions of subjects whose presence, when noted, is systematically distorted. Scholars in the fields of colonial slavery and women’s history more broadly understand and contend with scant sources from the enslaved perspective, and this is particularly true in the colonial British Caribbean.

This study also draws attention to the nature of the archives that inform historical works on slavery by employing a methodology that purposely subverts the overdetermining power of colonial discourses. By changing the perspective of a document’s author to that of an enslaved subject, questioning the archives’ veracity and filling out miniscule fragmentary mentions or the absence of evidence with spatial and historical context our historical interpretation shifts to the enslaved viewpoint in important ways. As previous scholarship has generated substantial knowledge about how enslaved women made meaning in their lives despite commodification and domination, my book does not simply seek to recover enslaved female subjects from historical obscurity. Instead, it makes plain the manner in which the violent systems and structures of white supremacy produced devastating images of enslaved female personhood, and how these pervade the archive and govern what can be known about them. Rather than leaving enslaved women “vulnerable to the readings and misreadings of whoever chooses to make assumptions about them,”8 my book probes the construction of enslaved women in the archival records, using methods that at once subvert and illuminate biases in these accounts in order to map a range of life conditions that profoundly challenge assumptions about the “slave experience” in Caribbean systems of domination.

What would a narrative of slavery look like when taking into account “power in the production of history?” That is, how do slaveholders’ interests affect how they document their world, and in turn, how do these very documents result in persistent historical silences?9 What would it mean to be critical of how our historical methodologies dependent on such sources often reproduce these silences? There is not a paucity of sources about slavery in the Caribbean from the words and perspectives of white authorities and slave owners. In fact, there are vital archival materials that describe the contours of enslaved women’s work and reproduction in the Caribbean. Using sources such as probate records, inventories of property, and descriptions of punishment and profit, scholars have mined the words and worlds of colonial authorities for clues to how the enslaved lived, worked, reproduced, and perished. Indeed, there are few if any new sources in this field; and Dispossessed Lives uses some of these same records but draws different conclusions by productively mining archival silences and pausing at the corruptive nature of this material.10 The objectification of the enslaved allowed authorities to reduce them to valued objects to be bought and sold, used to produce profit and to retain and bequeath wealth. It also made the enslaved disposable when they could no longer labor for profit. This same objectification led to the violence in and of the archive. Enslaved women appear as historical subjects through the form and content of archival documents in the manner in which they lived: spectacularly violated, objectified, disposable, hypersexualized, and silenced. The violence is transferred from the enslaved bodies to the documents that count, condemn, assess, and evoke them, and we receive them in this condition. Epistemic violence originates from the knowledge produced about enslaved women by white men and women in this society, and that knowledge is what survives in archival form. With sole reliance on the empirical matter of the eighteenth-century Caribbean, we can only create historical narratives that reproduce these violent colonial discourses. The work of this book is to make plain how and why this knowledge was created and reproduced, and to employ new methodologies that disrupt this process in order to illuminate subjugated, “marginalized and fugitive knowledge [and perspectives] from,” enslaved women.11

In each chapter I contend with the historical paradox and methodological challenges produced by the near erasure of enslaved women’s own perspectives, in spite and because of the superabundance of words white Europeans wrote about them. By applying theoretical approaches to power, the production of text, and constructions of race and gender to the written archive, I question historical methods that search for archival veracity, statistical substantiation, and empiricism in sources wherein enslaved women are voiceless and objectified. The subjects in this study, the laborers, the enslaved women, men, and children, lived their “historical” lives as numbers on an estate inventory or a ship’s ledger and their afterlives often shaped by additional commodification. The very call to “find more sources” about people who left few if any of their own reproduces the same erasures and silences they experienced in the eighteenth-century Caribbean world by demanding the impossible. Paying attention to these archival imbalances illuminates systems of power and deconstructs the influences of colonial constructions of race, gender, and sexuality on the sources that inform our work. This enables a nuanced engagement with the layers of domination under which enslaved women and men endured, resisted, and died. This is a methodological project concerned with the ethical implications of historical practice and representations of enslaved life and death produced through different types of violence.

Violence pervades the histories of slavery and this book. The violence committed on enslaved bodies permeates the archive, and the methods of history heretofore have not adequately offered the vocabulary to reconstitute “the depth, density, and intricacies of the dialectic of subjection and subjectivity” in enslaved lives.12 A legible and linear narrative cannot sufficiently account for the palimpsest of material and meaning embedded in the lives of people shaped by the intimacies and ubiquity of violence. Therefore, this book dwells on violence in its many configurations: physical, archival, and epistemic. The most obvious instances are physical—the ways violence inflicted on enslaved bodies turned them into objects in slave societies. Chapter 5 features and reproduces the inordinate accounts of enslaved women’s beatings in the records of the slave trade abolition debates. This reproduction brings to the fore how the excessive nature of such images works to silence these violent experiences beneath the titillated gazes of white men, abolitionist sensationalism, and historiographical skepticism, as well as our unavoidable complicity in replicating these accounts in order to historicize them.

Violence, then, is the historical material that animates this book in its subtle and excessive modes—on the body of the archive, the body in the archive and the material body.13 Focusing on the “mutilated historicity” of enslaved women (the violent condition in which enslaved women appear in the archive disfigured and violated), this book shows how “the violence of slavery made actual bodies disappear.”14 For example, Chapter 4 assesses execution records of enslaved women and men to challenge our understanding of colonial laws. In a system that forbade the enslaved a legal voice, the arbitrary and capricious nature of enslaved “crime” and punishment comes to the fore and challenges our readings of enslaved resistance. It also explicates the reach of these laws, which in 1768 demanded that the bodies of executed slaves be weighted down and thrown into the sea to prevent the enslaved community from rituals of mourning. Colonial power subsequently made the archive complicit in obscuring the offenses committed against the enslaved through the language of criminality. My work resists the authority of the traditional archive that legitimates structures built on racial and gendered subjugation and spectacles of terror. This violence of slavery concealed enslaved bodies and voices from others in their own the time and we lose them in the archive due to those systems of power and violence. Each chapter contends with these circumstances and uses different methods to draw out the link between violence, archival disappearance, and historical representation in the fragmentary records in which enslaved women materialize. The nature of this archive demands this effort.

Dispossessed Lives uses archival sources at times “for contrary purposes.”15 I stretch archival fragments by reading along the bias grain to eke out extinguished and invisible but no less historically important lives.16 In Chapter 3, for example, I use the court case of sexual entanglement between two white men and a married white woman to discuss the ways the presence and expectations of enslaved women in Bridgetown gave white women particular forms of power. Beliefs about enslaved women also enabled a young enslaved boy, owned by one of the men in the case, to dress as a woman in order to access public spaces without being perceived as a threat. Here the absence of explicit representations of enslaved women does not mean they have no bearing on the subjectivities and possibilities for other people in this society. I purposely fill out their absence as one way to address the above methodological questions. Dispossessed Lives demonstrates what other knowledge can be produced from archival sources if we apply the theoretical concerns of both cultural studies and critical historiography to documents and sources. It is an argument that history can still be made, and we can gain an understanding of the past even as we consciously resist efforts to reproduce the lived inequities of our subjects and the discourses that served to distort them.

Within the scope of this book I make two interventions into the extant literature on slavery in the Atlantic world. First, I argue that close attention to the specificities of urban slavery challenges scholarly representations of plantation slavery as more violent and spatially confining than slavery in other locales.17 To do this, I map how urban slave owners constructed and used architectures of terror and control on this seemingly mobile enslaved population through imprisonment, public punishment, and legal restrictions. Second, much of the previous historical scholarship on slavery influenced by the crucial Civil Rights and Black Power activism of the 1960s and 1970s focuses on enslaved resistance, a vital (and decades long) effort to gain insight into the “agency” of enslaved people and to refute earlier depictions of the enslaved as passive and submissive.18 The agency of enslaved and free(d) people of color, however, was more complex than the “liberal humanist” framework allows.19 We need to examine the excruciating conditions faced by enslaved women in order to understand the significance of their behaviors within the confounding and violent world of the colonial Caribbean. Finally, the centrality of gender in this study illuminates how African and Afro-Caribbean women experienced constructions of sexuality and gender in relation to white women and, as important, how enslaved women’s subaltern positions in slave society shaped the ways they entered the archive and, consequently, history.

A significant amount of scholarship on Atlantic slavery necessarily highlights life in the sugar plantation complex.20 Certainly, the majority of enslaved Africans and Afro-Caribbean people lived and died producing sugar for mass exportation from the Caribbean. But a focus on the rural conditions of slavery leaves the urban context underexamined and too easily subject to generalizations. Scholarly distinctions between rural and urban slavery tend to create a rigid dichotomy between the violence of rural slavery and the mobility and less arduous conditions of urban life, ignoring systems of surveillance and control in urban architectures and spaces. In addition, the predominantly domestic labor performed by enslaved women in towns might be read as less dangerous than field labor. To be sure, the enslaved who worked in sugar production were more vulnerable to early deaths, lack of sustenance, and the terror of plantation punishments. However, this did not mean that domestic or urban labor was necessarily easier and less constraining or violent. Dispossessed Lives reconsiders these assertions by examining the continuities and distinctions of violence from the planation to the urban complex. I explore the mechanisms and technologies created and employed by colonial authorities to control an enslaved population outside the confines of a plantation or the surveillance of an overseer. Although not large in terms of area, nor as densely populated as other Caribbean towns, Bridgetown sustained a significant population of urban slaves who labored under the duress of strict laws limiting their movement and architectures—both the structures of policy and the built environment—that ensured their confinement and punishment. Moreover, the surplus enslaved and female population of this town allowed slaveowners to turn enslaved women into sexual objects for incoming soldiers and sailors, a lucrative informal economy for their owners. Examining the degree to which colonial authorities utilized public punishments and structures of confinement complicates discussions of the possibilities of freedom and mobility in urban enslavement.

Since the late 1990s, scholars from a range of fields, including history, have challenged and refined the concept of agency as it applies to enslaved people. In her now definitive book, Saidiya Hartman argues that agency connotes the idea of “will” and “intent,” both of which were foreclosed by the legal condition of chattel slavery.21 Walter Johnson contends that agency as a trope originated from noble origins in the Civil Rights era but should be carefully interrogated for the conflation of its meaning with resistance and humanity in slavery scholarship.22 These scholars argue that the issue of “redress” is inescapable in writing histories of black life as the legacies of racism, racialized sexism, and poverty continue to haunt our present. In this effort, Hartman’s concerns shed light on the contradictions, exclusions, and demands of black people in post-emancipation liberal humanist discourses of rights and duties.23 She asks us to consider to what extent our work on the past is in service of redress and therefore what is the historian’s relationship to her subjects? To what end do we write these narratives?24

At stake here are the ways in which scholars, working within the paradigm of traditional African American historiography, insist that agency—akin to resistance—is still the most appropriate lens through which to examine slave life.25 Stephanie Camp contends that “slave resistance in its many forms is a necessary point of historical inquiry, and it continues to demand research.”26 Camp recognizes that studies of resistance have changed but, she argues, we “need not [abandon] the category altogether.”27 The present study troubles similar tropes of agency in Chapters 2 and 3 by examining the lives of white and free(d) women of color whose social and economic power relied on patriarchy and slave ownership.28 In Chapter 2 I address this issue in relationship to Rachael Pringle Polgreen, a mixed-race slave-owning woman in Barbados.29 Using the scholarship of Michel-Rolph Trouillot and Saba Mahmood, I question the application of sexual agency to enslaved and free(d) women’s sexual relations with white men in the context of this slave society where many enslaved and free women were subjected to unequal power relations and violence. Focusing specifically on women also deconstructs “resistance” as armed, militaristic, physical, and triumphant—a vision of resistance particularly resonant in the Caribbean with its histories of large-scale uprisings.

In counterpoint to definitions of agency, the concept of “social death” addresses how the enslaved were constrained by law, commodification, and subjection. In recent years, scholars have expanded on Orlando Patterson’s pivotal text Slavery and Social Death (1982), detailing the process by which Africans were made into property and how the condition of slavery in the past adversely affects how they can be accounted for historically. Still, prominent scholars reassert the imperative of resistance studies. In Vincent Brown’s important analysis of social death, he urges us away “from seeing slavery as a condition to viewing enslavement as a predicament, in which enslaved Africans and their descendants never ceased to pursue a politics of belonging, mourning, accounting, and regeneration.”30 Chapter 4, however, reminds us of the extent of power wielded by authorities and how the enslaved were subjected to arbitrary executions at the caprice of their owners and colonial officials, therefore limiting their strategies of mourning and shaping the perceptions of enslaved humanity and resistance.

Arguably, as many have noted, concepts of agency, resistance, and social death, perhaps even more than in other historical fields, continue to influence the ways we write and think about the enslaved and about systems of slavery and domination. Dispossessed Lives maintains that these historiographical debates are as important as illuminating the actions of the enslaved, because they have implications for what we have come to know and the limits of what we can know about the history of slavery. While the majority of studies of slavery have focused on the antebellum U.S. South, the British Caribbean offers a different tale, one in which slavery depended on a factory of violence in sugar production unsurpassed in North America. Life spans for most of the enslaved were brief and the physical distance from imperial control allowed particular types of atrocities on their bodies. On an island like Barbados, where sustained or permanent flight was nearly impossible, “rival geographies”—spaces created by the enslaved in defiance of the restrictions of plantation life—were threatened by surveillance, dangerous waterways, and deplorable material conditions.31 This study does not suppress the historical efforts of enslaved people to resist their circumstances. Rather, it presents the agonizing decisions they made in the face of violent retribution from colonial authorities. Dwelling on these uncomfortable junctures in history highlights the messy and contradictory behaviors of enslaved people. This book’s theoretical underpinnings at once read along the bias grain of the archive32 and against the politics of the historiography to gain nuanced understandings of what Avery Gordon calls “complex personhood” and the minute details of fragmentary lives that are challenging for historians to access.33

The fields of women’s and gender studies and black feminist theory give significant attention to knowledge production and the intersectional experiences of women; and these fields frame the questions with which I approach this history and these enslaved female subjects. This study argues that there was something particular about being enslaved and female in slave societies even as it resists more traditional concepts of gender; it dwells purposely on feminist epistemological questions concerning how (historical) knowledge is produced about enslaved female subjects through the archive. I draw on a range of interdisciplinary black feminist scholars, including historians, cultural studies scholars, and novelists who interrogate how black women have been represented historically and contemporarily; their sexual violations; and their hypersexualized images.34 Moreover, these scholars use analyses of race and gender to destabilize the power of dominant knowledge and representations of women of the African diaspora. My focus on the centrality of enslaved women to the project of slavery follows in the wake of such work and elucidates the manner in which their specific sexualized identities and social constructions placed them in particular roles and positions in Caribbean and Barbadian slave societies. It also demonstrates how gender and sexuality were shaped and produced in a society where white and Afro-Barbadian women outnumbered men. Building on Jennifer Morgan’s scholarship, which illustrates how reproduction signified a central experience for enslaved women, I consider the ways in which sexuality was inhabited, performed and consequential for urban female slaves.

Finally, this book examines our own desires as historical scholars to recover what might never be recoverable and to allow for uncertainty, unresolvable narratives, and contradictions. It begins from the premise that history is a production as much as an accounting of the past, and that our ability to recount has much to do with the conditions under which our subjects lived. This is project concerned with an ethics of history and the consequences of reproducing indifference to violence against and the silencing of black lives. Our responsibility to these vulnerable historical subjects is to acknowledge and actively resist the perpetuation of their subjugation and commodification in our own discourse and historical practices. It is a gesture toward redress.