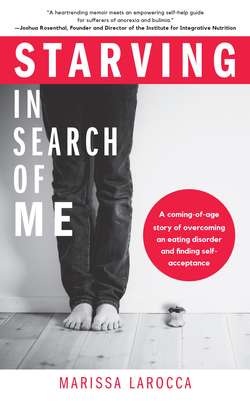

Читать книгу Starving In Search of Me - Marissa LaRocca - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1 WHY ARE YOU SO QUIET?

-

In this first section, I’ll share with you my personal story with as much gritty emotional truth as I can. I’ll tell you about how I felt like an outcast throughout my school years due to being painfully introverted, how I related to my family, how I felt plagued with fear and confusion around my sexuality beginning around puberty, and how I struggled to transition from adolescence into adulthood with only a frighteningly subtle sense of who I was and what I needed to be happy.

Early Struggles with Social Anxiety and Fitting In

To this day, I’m not sure there’s anything more terrifying than entering the cafeteria alone on the first day of school. For an eternal moment, you hover in the entranceway, watching everyone take a seat as if choreographed, as if summer was just another day gone by and no one’s kinships have skipped a beat. Then the bell rings with a frantic shrill, and soon enough you’re the only one left standing. What do you do? Your backpack weighs on your adolescent shoulders, heavy with too many textbooks. It’s too late to be inconspicuous. You have to make a decision. Now really, what do you do?

Both literally and metaphorically, I’ve never really known where to sit. So I spent many of my elementary and high school lunch periods hiding out in a stall in the girls’ bathroom, discreetly peeling the aluminum foil off my peanut butter and jelly sandwich, hoping to God no one would notice my feet under the door.

From the time I was very young, I sensed there was something different about me. I was first exposed to people my age at a Catholic elementary school, and it didn’t come naturally to me to reach out of my comfort zone and make friends. I was highly observant, perceptive, and painfully shy. While the other kids goofed off during recess and competed for attention during gym class, I sat watching them, harboring this feeling that there were infinite universes between me and other human beings. A wallflower by nature, I did the best I could to conceal my nerves and blend in. But I very quickly learned that keeping to myself was a widely unacceptable manner of existing.

“Why are you so quiet?” my classmates would ask me, interrupting the concentrated effort I put into trying to make myself invisible.

“I don’t know,” I’d reply with a bashful grin and eyes that begged them to leave me alone. Then I’d return to my default personality—well behaved and petrified. Eventually, through the years, my classmates stopped asking questions, and I was just the quiet girl in class who did all her homework and rarely raised her hand.

I remember getting on the school bus, always choosing the third or fourth seat. The middle of the bus, slightly favoring the front, felt safest to me. Of course, the back of the bus was reserved for the cooler kids, the rowdy troublemakers and the itchy little perverts. And the first two rows were for those with some quality about them considered by the cooler kids to be a drastic impediment—the boy with the stutter, the girl with the retainer that wrapped around her whole head. So by choosing the middle, I made a commitment to my place within the unspoken social hierarchy—I wasn’t cool, but I wasn’t a “loser” either. I was just there, lost beneath the hum of the school bus engine and the indistinct chatter, wanting to draw as little attention to myself as possible.

My parents were never religious people. I’m pretty sure they sent my sister and I to Catholic school thinking that we’d get a better education than in public school, and we’d be safer. And that may have been true. But I do wonder to what extent I may have been negatively impacted by the years of seeing Jesus nailed to a cross, with the nuns and priests reinforcing this as the ultimate symbol of sacrifice. Throughout my formative years, when my mind was most impressionable, I was taught that sinning is bad; people who sin burn forever in hell. God was a powerful man in the sky and I was a little girl on the ground being evaluated for the “goodness” or “badness” of my every decision. Then they told me I was already made of sin for being a human being because Adam and Eve ate an apple that God told them not to eat. And so every morning after the first school bell, my entire class had to recite the Our Father prayer in unison. “Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. Amen.”

In the seventh grade, after six straight years spent wearing green knee socks and a plaid uniform, I switched from Catholic school to public school, where I felt even more out of place than before. It was 1998 and girls wore makeup, bellbottom jeans, and platform shoes. They chewed gum, spoke out, even cursed in class. The boys were just as much of a leap in the opposite direction of what I was used to. There were sporty kids and preppy kids and drug dealer kids (I had won a D.A.R.E. essay contest in the fifth grade, and up until this point, I thought drugs were something I would never encounter in real life). Everyone seemed to be part of a tightknit clique or a gang, and as far as I was concerned, they were all aliens from another planet. Needless to say, I felt culture-shocked and naive, ill-equipped to navigate this strange new land of pubescent people.

I remember shaking, literally shaking with social anxiety, before I knew what social anxiety even was. I trembled in the hallways and in all my classes each time a teacher made me read aloud or uttered the dreaded phrase, “Everybody find a partner.” My stomach was perpetually twisting, tightening around its own knots.

The Pressures of Puberty

About halfway through my adolescence, I suddenly felt an enormous amount of pressure to find a boyfriend, to experience my first kiss, and to start experimenting with my body. Suddenly, everyone at school was dating, not just the first-to-bloom kids at the top of the social totem pole. But for me, there were obstacles. For starters, my hormones weren’t making me hungry for boys. Second, I still didn’t have an “in” with any particular group of people in my grade, nor was I willing to participate in contrived social activities like pep rallies and school dances. And third, possibly the biggest hurdle of all, was that I knew that in order to engage in any of these new experiences, I would have to become a woman in my parents’ eyes.

The thought of growing up felt somehow taboo to me, as if in doing so, I’d be letting down two of the only people I’d ever truly cared for. I’m not entirely sure what led me to feel this way. It could’ve been because both of my parents were very involved in my life and seemed very attached to being parents, and so perhaps I was afraid I’d hurt them if I was no longer their little girl. My home life and the role I played in my family as a child was the only comfort I’d ever really known. My parents’ love and approval was my greatest sense of security and self-esteem.

I grew up with one sibling, my twin sister, Kristy, and we had similar feelings of guilt attached to our impending developing selves. I recall, for example, hoping to God that Kristy would get her period for the first time before I did so that she could pioneer coping with the shame and embarrassment that would come with it. But sure enough, one day while playing volleyball in gym class, I felt a painful, burning sensation between my legs, and when I went to the bathroom, all I saw was red. Of course I panicked. I purchased a Kotex pad from the cold metal vending machine for feminine products (thank all the goodness in the world it wasn’t empty, and that I found a quarter in my book bag). Moments later, I found myself on a payphone with my mom, voice trembling, completely mortified, confessing to her that I was having my “time of the month” for the first time. My mom’s voice on the other end of the line was motherly and joyful. “We’ll have to celebrate when you get home,” she said. But I was afraid of what that celebration would entail. In fact, now that I was bleeding like a woman, I couldn’t imagine how life would go on.

This mortification around my femininity surfaced in many other ways as well. For one, I always felt awkward changing in front of other girls in the gym locker room. Long before it ever occurred to me I might be attracted to women, I felt “naughty” for being able to see other females undressing in my peripheral vision. My body was a different body—not like theirs. My discomfort with my own parts was furthered by the fact that I didn’t shave my legs or armpits until high school, so I dreaded wearing shorts that would expose my hairy limbs.

In the lunchroom, boys would approach me from time to time, and it was always the same story: “Hi, my friend thinks you’re cute. He’s sitting over there. He wants to know if you’d like to go out sometime.” I always said no without looking, unable to imagine uttering the phrase to my parents, “I’m going out with a boy.” I was equally incapable of imagining myself batting my eyelashes and flirting playfully with a seventh-grade boy. I just wasn’t ready.

Things got confusing when I became friends with a girl named Jessica. Jessica was slightly more popular than I was. In my mind, she was my ticket into a higher popularity bracket, and so making sure she liked me was important. The problem was that every time Jessica was around me, I’d become filled with a paralyzing anxiety. When the second period bell rang, I’d begin trembling, knowing I was going to see her in my third period typing class. Eventually, I started going over to Jessica’s house and she would occasionally come over to mine. We did basic things together—played checkers, played video games, and ate dinner with either her parents or mine.

I don’t recall there being anything profound about our friendship, nor did we ever become particularly close. But it’s funny the way people sometimes enter our lives just to teach us things about ourselves. It’s funny the way a moment can shift you. One day I went over to Jessica’s house just as she and her mom were getting home from the grocery store. I went to the trunk of the car to help carry some of the groceries, but Jessica smiled and refused to allow me to help. Instead, she grabbed every plastic bag, her arms overloaded, and all I could think was, “That’s hot.” I don’t know why, or where the thought came from. But it turned me on somewhere in my body, the fact that she took it upon herself to spare me from this one silly chore. Days later, I woke up from a dream where Jessica was on top of me, making out with me. And all I thought was, “That’s interesting.”

My Parents’ Influence

Here’s something I’ve come to accept: we can’t deny the ways in which we are shaped by our upbringings—regardless of the intentions of our caretakers. Our parents play an undeniably significant role in influencing our personalities, our temperaments, and the ways we come to view the world, especially when we are young. Also, we are shaped by more than our experiences—we’re shaped by the meaning we assign to those experiences. That said, my parents are two of the most loving people on this earth and I’m grateful beyond words for them both. But I’d be leaving out an important part of my story if I didn’t include their effect on me as a teenager.

My mom was the primary caretaker for my sister and I throughout our developing years, while my dad worked very long hours as a salesman. She carried much of the burden of caring for two twin girls, often on her own, and dedicated much of her life to our wellbeing. Perhaps because of this, she was very overprotective of my sister and I growing up—nothing I did made it past her, and in her mind, imminent danger was always just ahead. As kids, my sister and I weren’t allowed to go over to our friends’ houses for sleepovers unless my mom met and approved of each friend’s parents—while this may have been appropriate for a period of time, it went on until we were well into our teens. She warned us time and again not to go to public bathrooms alone, not to talk to strangers, and to stay away from large, windowless vans. She opted to be a chaperone on most school trips; otherwise, we just wouldn’t go. There were times my sister and I even caught my mom listening in on phone calls with our friends.

While I understand now that my mom’s overly suspicious nature was rooted in her intention to keep me healthy and safe, as a young teenager with very little life experience, I had not yet reached the vantage point from which I could appreciate my mom’s intense involvement in my life for what it was. I knew only that I was anxious, confused, and curious about so many things still beyond my conception. I came to believe that freedom was dangerous. Freedom came with a price tag, and so it was difficult for me to develop an early sense of who I was. Nonetheless, the last thing I wanted to do was disappoint my mom, and so I made it my responsibility to earn her approval at any cost, even when it meant sacrificing my own need for more independence.

As for my dad, his larger-than-life personality has always been endearing, but it felt a bit intrusive to me as a sensitive adolescent as I struggled to connect with the quiet depths that would later define me. My dad has the kind of carelessly extroverted presence that spills all over the place, fills up rooms, and dominates the spaces he enters. As a child, my dad was my hero—the guy who took me to experience new things and made everything more fun and exciting. He made snowmen with me in the snow, played volleyball with me in the pool, and gave me piggyback rides on the living room carpet. But when the disease of becoming a woman set in, I had the sense that my dad didn’t know how to involve himself in my life in ways that would support my evolving emotional needs at the time.

Branching Out as an Individual

Although my sister and I had been around one another constantly for all our childhood years, by the time we reached high school, we each began to branch out more as individuals. No longer did we share the exact same friends, musical tastes, or clothing styles (pretty much the only things that matter when you’re a teenager). But this is not to say we “grew apart,” necessarily. Instead, the distance felt more like an unspoken agreement between our souls. The need to grow as separate beings and the desire to explore our budding selves had become too intense at this point to ignore. And although we were not yet mature enough to confide everything in one another throughout the rocky phases of self-discovery, in time, our separate journeys actually brought us closer.

When it came to socializing, Kristy and I were a little bit different. Kristy attempted to break away from a contained upbringing by having adventures with new people who enabled her to feel a new sense of freedom and possibility. I, on the other hand, went out and socialized in more conservative ways, cautiously collecting new experiences and reflecting on them. Kristy had different ways of dealing with her growing pains, too. She, a degree more rebellious than I, would wage wars with my parents, especially my mom, in the name of her independence. I remember angst-filled yelling matches during which my sister would argue for her God-given right to stay out past ten o’ clock, while my mother retorted back at her that she could live on her own if she wanted to make her own rules. I was different in that I avoided confrontation at all costs. Instead, I internalized a lot of my feelings and let fear control most of my decisions until eventually I did what all teenagers do. I started telling white lies to protect my parents from who I needed to become.

Another layer of oppression many people experience as adolescents has to do with society. My sister, who is a psychotherapist now, agrees that while adolescents are typically stereotyped as bratty or narcissistic in their quest to discover who they are, the need to formulate an identity at this age is so critical. And yet, it’s precisely at this age that we are first plagued with many responsibilities of adulthood. It’s no wonder so many teenagers are moved to rebel and express themselves through radical means; they’re not given the room to explore themselves as they go through one of the biggest transitions of their lives. Instead, society places all this weight on their shoulders.

Another important element to take into consideration here is that not every teenager’s temperament is the same. My sister and I have always been exceptionally deep, observant, highly sensitive people. So our need to reflect and take our time with developing was perhaps even greater than for the average person. Not having this time caused me a great deal of overwhelm and anxiety.

Hallelujah, I’m a Lesbian

I didn’t date anyone until the eleventh grade. My first boyfriend, Joe, had sweaty hands and a frog-like face. He wore emo glasses, played guitar, and listened to Green Day. As horrible as it is to say, my agreeing to date Joe was more of an “all right, let’s get this boyfriend thing over with” thing than anything based on any sort of attraction. I remember my first kiss. Joe and I were at the movies, and we’d planned to plant our mouths on one another’s for the first time as soon as the lights went dark in the theater. He’d just finished eating a Butterfinger, and I could smell the candy on his breath before I tasted it. It was an unremarkable kiss, devoid of sparks, triggering zero emotions (at least on my end). But the possibility that I might be a lesbian still had yet to cross my mind. I had so little experience socially and romantically that I chalked up the lack of fireworks to the fact that I was a novice, that I hadn’t yet discovered “my type,” or that I wasn’t popular enough to attract someone I could actually be attracted to.

Shortly after Joe came Mike and Jon and Chris and Matt. To me, they were all the same. I went through the motions of what I thought it meant to flirt, though I was only mimicking what I saw other girls doing and it came with extreme discomfort. I don’t know how else to describe the role I felt forced into each time I sat in the passenger seat of a guy’s car, except to say that I felt in every sense a passenger. Next to men, I have always felt as if I should be expected to concede…to their agendas, to their ideas, and to their physical desires. They were never in tune with me emotionally; instead, they had a predetermined sense of how I should fit myself into their lives. Even when certain guys worshipped me for my intelligence and qualities I appreciate being noticed for, it still felt as if I was this “thing” to them, an accessory they could show off and from which they could derive satisfaction.

My realizing-I-was-gay story is funny, in that it was literally a realization I came to overnight. I was dating Matt at this point, a fairly decent looking boy I had met in acting class. Sometimes on school nights Matt would pick me up in his van to go to the local diner for “hot chocolate.” What this really meant is that I’d watch him stuff his face with a disgusting cheeseburger, and then he’d ask me for a blowjob in the parking lot.

Eventually came the day our acting class took a field trip to see Wicked on Broadway, and Matt introduced me to his friend Cat. Within seconds of meeting Cat, I felt as if I had known her for years. There was something familiar and endearing about her—perhaps I was sensing echoes of my future self, already aware she would shape my life in a way that would forever shift me. But never before had I felt so instantly compatible with another person. Cat was bubbly and affectionate; she laughed at the things I said and made me feel comfortable in my skin.

One night shortly after we met, Cat and I were chatting on AOL instant messenger when the possibility occurred to me that I might be attracted to women. Matt was constantly flirting with other girls. The status of having a boyfriend was the only part of being with Matt that actually appealed to me. Other than that, he didn’t make my heart beat any faster. Something just wasn’t right. Struck with the sudden urge to confide in someone, I told Cat how I’d been feeling. To my surprise, Cat replied, “I’ve been wondering the same thing about myself.” And with that, we agreed to “test” ourselves out on one another, despite both having boyfriends. The very next night, Cat came over, and after a few shots of vodka borrowed from my parents’ liquor cabinet, she leaned in to me and said, “I told you I wouldn’t be afraid.” Then we kissed, and electricity ran through every part of my body. Overcome with a combination of lust and shame, I felt desire for the first time. I wanted more.

For a moment, I sought refuge in my new discovery. I asked myself, Is this why I’ve felt different all my life? Because I’m a lesbian? Is this why I’ve never felt like other girls? Suddenly, everything made sense. I could read the writing on the wall.

Now that I’d resolved this tremendous part of my identity, I finally felt motivated to take the risks required to get to know myself more intimately. This is when I began to tell more substantial lies to my parents, like the time I said I was staying at a friend’s house for the day so I could take an Amtrak to Philadelphia to visit Alex, a girl I had met online, and experiment with her sexually; or the several times I snuck out my bedroom window, or smuggled a girl in through it. It was all pretty harmless, honestly. But it was harmful in the way that each time I told a lie, I reinforced something terrible in my own mind: that I had to keep secrets in order to get what I wanted.

My Sister’s Encounter with Self-Harm

Unbeknownst to me, around the time I discovered I liked girls, my sister had discovered the same thing about herself. In fact, she’d been discreetly fooling around with a girl for a couple of months (I’ll call the girl “Hanna”) and was in the midst of having her heart broken for the very first time. As I found out from my sister later, Hanna was moody, mentally unstable, and perhaps sexually confused. She took Kristy on a lust-filled roller coaster ride only to eventually go back to her boyfriend, leaving Kristy in the dust. The fling ended dramatically and abruptly with Hanna being hospitalized for cutting herself.

The day I found out what Kristy had gone through was the day my mom noticed scabbed streaks of red emerging from Kristy’s long-sleeved shirt and demanded that she roll back her sleeves to expose her forearms. Kristy refused as adamantly as I’d ever heard her refuse anything, but my mom persisted until she finally forced Kristy to reveal her arms. The gasp that came from my mom next was the gasp that changed everything. My sister had cut herself deeply with a box cutter—so deeply, in fact, that she has scars to this day.

Recently, I asked my sister’s permission to include this part of the story in this book and also asked her if she could tell me more. She sent me the following in a text:

“I did it because I was in pain and it didn’t seem like anyone really knew. I was a depressed, closeted homo in love with a very disturbed yet very alluring girl. I did it because I felt trapped. Seeking support around this would have meant ‘coming out’ and I just wasn’t ready for all that yet. I wasn’t even sure yet myself what I was. At the time I was aware that in a sick way I wanted Hanna to find out what I’d done to myself. I wanted her to know how much I cared about her and how hurt I was about her hurting herself. I wanted her to see her own reflection in me. I wanted her to see that perhaps we were more alike than she knew. In a weird way, cutting myself brought me to terms with the level of pain and numbness I was experiencing. The fact that I could harm myself to such an extent and barely feel it was evidence of my suffering, and so was the blood. It was proof of my existence, and so are the scars.”

After my sister’s encounter with self-harm, there was a significant shift in my family’s dynamics. My mother and father, concerned as any parents would be, took every measure they could to prevent Kristy from hurting herself again, from an initial trip to the emergency room to getting Kristy enrolled into psychotherapy. Patronizing doctors and concerned family members asked my sister, “Why would you do this to your precious skin?” Eventually, my mom sought treatment of her own and began seeing a therapist for a time, who I think pushed her to let Kristy and I have more trust and independence. This ultimately led to my mom pulling back and giving Kristy and I more room to grow as individuals.

My sister and I came out as gay a couple of years later, and my parents actually took the news lovingly and well. But still we had this in common: our first notions of romantic love were that it involved things we had to conceal. Euphoria and joy were feelings to be ashamed of, feelings we had to steal.