Читать книгу Born to Be Posthumous - Mark Dery - Страница 7

INTRODUCTION A GOOD MYSTERY

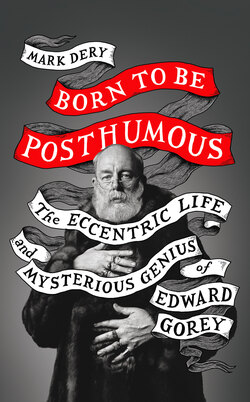

ОглавлениеDon Bachardy, Portrait of Edward Gorey (1974), graphite on paper. (Don Bachardy and Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica, California. Image provided by the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.)

Edward Gorey was born to be posthumous. After he died, struck down by a heart attack in 2000, a joke made the rounds among his fans: During his lifetime, most people assumed he was British, Victorian, and dead. Finally, at least one of the above was true.

In fact, he was born in Chicago in 1925. And although he was an ardent Anglophile, he never traveled in England, despite passing through the place on his one trip across the pond. He was, however, intrigued by death; it was his enduring theme. He returned to it time and again in his little picture books, deadpan accounts of murder, disaster, and discreet depravity with suitably disquieting titles: The Fatal Lozenge, The Evil Garden, The Hapless Child. Children are victims, more often than not, in Gorey stories: at its christening, a baby is drowned in the baptismal font; one hollow-eyed tyke dies of ennui; another is devoured by mice. The setting is unmistakably British, an atmosphere heightened by Gorey’s insistence on British spelling; the time is vaguely Victorian, Edwardian, and Jazz Age all at once. Cars start with cranks, music squawks out of gramophones, and boater-hatted men in Eton collars knock croquet balls around the lawn while sloe-eyed vamps look on.

Gorey wrote in verse, for the most part, in a style suggestive of a weirder Edward Lear or a curiouser Lewis Carroll. His point of view is comically jaundiced; his tone a kind of high-camp macabre. And those illustrations! Drawn in the six-by-seven-inch format of the published page, they’re a marvel of pen-and-ink draftsmanship: minutely detailed renderings of cobblestoned streets, no two cobbles alike; Victorian wallpaper writhing with serpentine patterns. Gorey’s machinelike cross-hatching would have been the envy of the nineteenth-century printmaker Gustave Doré or John Tenniel, illustrator of Lewis Carroll’s Alice books. Hand-drawn antique engravings is what they are.

Gorey first blipped across the cultural radar in 1959, when the literary critic Edmund Wilson introduced New Yorker readers to his work. “I find that I cannot remember to have seen a single printed word about the books of Edward Gorey,” Wilson wrote, noting that the artist “has been working quite perversely to please himself, and has created a whole little world, equally amusing and somber, nostalgic and claustrophobic, at the same time poetic and poisoned.”1

That “little world” has won itself a mainstream cult (to put it oxymoronically). Millions know Gorey’s work without knowing it. Whether they noticed his name in the credits or not, Boomers and Gen-Xers who grew up with the PBS series Mystery! remember the dark whimsy of Gorey’s animated intro: the lady fainting dead away with a melodramatic wail; the sleuths tiptoeing through pea-soup fog; cocktail partiers feigning obliviousness while a stiff subsides in a lake. Then, too, every Tim Burton fan is a Gorey fan at heart. Burton owes Gorey a considerable debt, most obviously in his animated movies The Nightmare Before Christmas and Corpse Bride. Likewise, the millions of kids who devoured A Series of Unfortunate Events, the young-adult mystery novels by Lemony Snicket, were seduced by a narrator whose arch persona was consciously modeled on Gorey’s. Daniel Handler—the man behind the nom de plume—calls it “the flâneur.” “When I was first writing A Series of Unfortunate Events,” he says, “I was wandering around everywhere saying, ‘I am a complete rip-off of Edward Gorey,’ and everyone said, ‘Who’s that?’ ” That was in 1999. “Now, everyone says, ‘That’s right, you are a complete rip-off of Edward Gorey!’”

Neil Gaiman’s dark-fantasy novella Coraline bears Gorey’s stamp, too. A devout fan since childhood, when he fell for Gorey’s illustrations in The Shrinking of Treehorn by Florence Parry Heide, Gaiman has an original Gorey hanging on his bedroom wall, a drawing of “children gathered around a sick bed.”2 Gaiman’s wife, the dark-cabaret singer Amanda Palmer, references Gorey’s book The Doubtful Guest in her song “Girl Anachronism”: “I don’t necessarily believe there is a cure for this / So I might join your century but only as a doubtful guest.”3

His influence is percolating out of the goth, neo-Victorian, and dark-fantasy subcultures into pop culture at large. The market for Gorey books, calendars, and gift cards is insatiable, buoying indie publishers like Pomegranate, which is resurrecting his out-of-print titles. Since his death, his work has inspired a half dozen ballets, an avant-garde jazz album, and a loosely biographical play, Gorey: The Secret Lives of Edward Gorey (2016). Of course, there’s no surer sign that you’ve arrived than a Simpsons homage. Narrated in verse, in a toffee-nosed English accent, and rendered in Gorey’s gloomy palette and spidery line, the goofy-creepy playlet “A Simpsons ‘Show’s Too Short’ Story” (2012) indicates just how deeply his work has seeped into the pop unconscious.

But the leading indicator of Gorey’s influence is his transformation into an adjective. Among critics and trend-story reporters, “Goreyesque” has become shorthand for a postmodern twist on the gothic—anything that shakes it up with a shot of black comedy, a jigger of irony, and a dash of high camp to produce something droll, disquieting, and morbidly funny.

But is that all we’re talking about when we talk about Gorey? An aesthetic? A style? The way we wear our bowler hats?

Truth to tell, we hardly know him.

Gorey’s work offers an amusingly ironic, fatalistic way of viewing the human comedy as well as a code for signaling a conscientious objection to the present. Handler attributes Gorey’s enduring appeal to the sophisticated understatement and wit of his hand-cranked world, dark though it may be—a sensibility that stands in sharp contrast to the Trumpian vulgarity of our times. The Gorey “worldview—that a well-timed scathing remark might shame an uncouth person into acting better—seems worthy to me,” says Handler.

Like Handler, the steampunks and goths with Gorey tattoos who flock to the annual Edwardian Ball, “an elegant and whimsical celebration” inspired by Gorey’s work, dream of stepping into the gaslit, sepia-toned world of his stories.4 Justin Katz, who cofounded the Ball, believes revelers, many of whom come dressed in Victorian or Edwardian attire, are drawn by the promise of escape from our “Age of Anxiety,” a “chaotic time” of “accelerated media” that is “stressful and rootless” for many.

Gorey, it should be noted, groaned at being typecast as the granddaddy of the goths and would have shrunk from the embrace of neo-Victorians. “I hate being characterized,” he said. “I don’t like to read about the ‘Gorey details’ and that kind of thing.”5 There was more—much more—to the man than charming anachronisms and morbid obsessions.

Only now are art critics, scholars of children’s literature, historians of book-cover design and commercial illustration, and chroniclers of the gay experience in postwar America waking up to the fact that Gorey is a critically neglected genius. His consummately original vision—expressed in virtuosic illustrations and poetic texts but articulated with equal verve in book-jacket design, verse plays, puppet shows, and costumes and sets for ballets and Broadway productions—has earned him a place in the history of American art and letters.

Gorey was a seminal figure in the postwar revolution in children’s literature that reshaped American ideas about children and childhood. Author-illustrators such as Maurice Sendak, Tomi Ungerer, and Shel Silverstein spearheaded the movement away from the bland Fun with Dick and Jane fare of the Wonder Bread ’50s toward a more authentic representation of the hopes, anxieties, terrors, and wonders of childhood—childhood as children live it, not as the angelic age of innocence adults imagine it to be, a sentimental chromo handed down from the Victorians. Gorey was never a mass-market children’s author for the simple reason that publishers, despite his urgings, refused to market his books to children. They were squeamish about the darkness of his subject matter, not to mention the absence of anything resembling a moral in his absurdist parables.

Nonetheless, the Wednesday and Pugsley Addamses of America did read Gorey. In a nice twist, Boomer and Gen-X fans raised their children on The Gashlycrumb Tinies, turning a mock-moralistic ABC that plays the deaths of little innocents for laughs (“A is for Amy who fell down the stairs / B is for Basil assaulted by bears …”) into a bona fide children’s book. Some of those kids grew up to be cultural shakers and movers. The graphic novelist Alison Bechdel, whose scarifying tales of her childhood earned her a MacArthur “genius grant,” is a careful student of Gorey’s “illustrated masterpieces,” as she calls them; the Gorey anthology Amphigorey is among her ten favorite books.6 Following Gorey’s lead, she and others have turned traditionally juvenile genres—the comic book, the stop-motion animated movie, the young-adult novel—to adult ends, opening the door to a new honesty about the moral complexity of childhood. Bechdel’s graphic memoir Fun Home, an unflinching exploration of growing up lesbian in the shadow of her abusive father, is only one of a host of examples.

The contemporary turn toward an aesthetic, in children’s and YA media, that is darker, more ironic, and self-consciously metatextual (that is, aware of, and often parodying, genre conventions and retro styles) would be unthinkable without Gorey. Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children (2011), a bestselling YA novel by Ransom Riggs, is typical of the genre. Unsurprisingly, it was inspired by the “Edward Gorey–like Victorian weirdness” of the antique photos Riggs collected, “haunting images of peculiar children.”7 He told the Los Angeles Times, “I was thinking maybe they could be a book, like The Gashlycrumb Tinies. Rhyming couplets about kids who had drowned. That kind of thing.”8

Gorey’s art—and highly aestheticized persona—foreshadowed some of the most influential trends of his time. His work as a cover designer and illustrator for Anchor Books in the 1950s put him at the forefront of the paperback revolution, a shift in American reading habits that, along with TV, rock ’n’ roll, the transistor radio, and the movies, helped midwife postwar pop culture. Before the Beats, before the hippies, before the Williamsburg hipster with his vest and man bun, Gorey was part of a charmed circle of gay literati at Harvard that included the poets Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery; O’Hara’s biographer calls Gorey’s college clique “an early and elitist” premonition of countercultures to come, at a time—the late ’40s—when there was no counterculture beyond the gay demimonde.9 Though he’d shudder to hear it, Gorey was the original hipster, a truism underscored by the uncannily Goreyesque bohemians swanning around Brooklyn today in their Edwardian beards and close-cropped hairstyles—the very look Gorey sported in the ’50s.

Before retro took up permanent residence in our cultural consciousness; before the embrace, in the ’80s, of irony as a way of viewing the world; before postmodernism made it safe to like high and low culture (and to borrow, as an artist, from both); before the blurring of the distinction between kids’ media and adult media; before the mainstreaming of the gay sensibility (in the pre-Stonewall sense of a Wildean wit crossed with a tendency to treat life as art), Gorey led the way, not only in his art but in his life as well.

Yet during his lifetime the art world and literary mandarins barely deigned to notice him or, when they did, dismissed him as a minor talent. His books are little, about the size of a Pop-Tart, and rarely more than thirty pages—mere trifles, obviously, undeserving of serious scrutiny. He worked in a children’s genre, the picture book, and wrote in nonsense verse. Even more damningly, his books are funny, often wickedly so. (Tastemakers take a dim view of humor.)

But the nail in Gorey’s coffin, as far as high-culture gatekeepers were concerned, was his status as an illustrator. For much of his lifetime, critics and curators patrolled the cordon sanitaire between serious art, epitomized by abstract expressionism, and commercial art, that wasteland of kitsch and schlock. Clement Greenberg, the high priest of postwar art criticism, dismissed all representational art as kitsch; illustration, it went without saying, was beneath contempt. Decades after abstract expressionism’s heyday, the art world was still doubling down on its disdain for the genre: a 1989 article in the Christian Science Monitor noted that prominent museums were “reluctant to display or even collect” illustration art, an observation that holds true to this day.10 By the same token, graduate programs discourage dissertations on the subject because, as a source quoted in the Monitor informed, “If you choose to get involved in a secondary art form, which is where American illustration fits in, you are regarded as a secondary art historian.”

Gorey didn’t help matters by standing the logic of the critical establishment on its head. He had zero tolerance for intellectual pretension and seemed to regard gravitas as dead weight, a millstone for the mind. Like the baroque music he loved, he had an exquisite lightness of touch, both in his inked line and in his conversation, which sparkled with quips and aperçus. He pooh-poohed the search for meaning in his work (“When people are finding meaning in things—beware,” he warned) and championed as aesthetic virtues (with tongue only partly in cheek) the inconsequential, the inconclusive, and the nonchalant.11

Those virtues, as well as Gorey’s persona—a pose that incorporated elements of the aesthete, the idler, the dandy, the wit, the connoisseur of gossip, and the puckish ironist, wryly amused by life’s absurdities—were steeped in the aestheticism of Oscar Wilde and in the ennui-stricken social satire of ’20s and ’30s English novelists such as Ronald Firbank and Ivy Compton-Burnett, both of whom, like Wilde, were gay.

Gorey’s own sexuality was famously inscrutable. He showed little interest in the question, claiming, when interviewers pressed the question, to be asexual, by which he meant “reasonably undersexed or something,” a state of affairs he deemed “fortunate,” though why that should be fortunate only he knew.12 To nearly everyone who met him, however, his sexuality was a secret hidden in plain sight. There was the bitchy wit. The fluttery hand gestures. The flamboyant dress: floor-sweeping fur coats, pierced ears, beringed fingers, and pendants and necklaces, the more the better, jingling and jangling. And that campy delivery, plunging into sepulchral tones, then swooping into near falsetto. “Gorey’s conversation is speckled with whoops and giggles and noisy, theatrical sighs,” wrote Stephen Schiff in a New Yorker profile. “He can sustain a girlish falsetto for a very long time and then dip into a tone of clogged-sinus skepticism that’s worthy of Eve Arden.”13 Many of his intellectual passions—ballet, opera, theater, silent movies, Marlene Dietrich, Bette Davis, Gilbert and Sullivan, English novelists like E. F. Benson and Saki—were stereotypically gay. Nearly everyone who met him pegged him as such.

Viewing Gorey’s art through the lens of gay history and queer studies reveals fascinating subtexts in his work and argues persuasively for his place in gay history, situating him in an artistic continuum whose influence on American culture has been profound.

“At the heart of all of Gorey, everything is about something else,” his friend Peter Neumeyer, the literary critic, once observed.14 In his life as well as his art, he embraced opposites and straddled extremes. His tastes ranged from highbrow (Balthus, Beckett) to middlebrow (Golden Girls, Buffy the Vampire Slayer) to lowbrow (true-crime potboilers, Star Trek novelizations, the Friday the 13th franchise). He was equally unpredictable in his critical verdicts, pitilessly skewering dancers in George Balanchine’s ballets yet zealously defending, with a perfectly straight face, William Shatner’s animatronic acting. Allowing that his work might hark back “to the Victorian and Edwardian periods,” he pulled an abrupt about-face, asserting, “Basically I am absolutely contemporary because there is no way not to be. You’ve got to be contemporary.”15

What you saw wasn’t always what you got. Take his name. It was too perfect. Edward fits like a dream because his neo-Victorian nonsense verse is modeled, unapologetically, on that of Edward Lear (of “The Owl and the Pussycat” fame). His mock-moralistic tales are set, more often than not, in Edwardian times. Moreover, Gorey was an eternal Anglophile, and Edward is one of the most English of English names, a hardy survivor of the Norman Conquest that dates back to Anglo-Saxon times, when it was Ēadweard—“Ed Weird” to modern eyes unfamiliar with Old English, an apt sobriquet for a legendary eccentric. (Did I mention that he lived, in his later years, in a ramshackle nineteenth-century house that he shared with a family of raccoons and a poison-ivy vine creeping through a crack in the living-room wall? Gorey was benignly tolerant of both infestations—for a while.)

As for Gorey, well, the thing speaks for itself: his characters often meet messy ends. The novelist and essayist Alexander Theroux, a member of Gorey’s social circle on Cape Cod, thinks “he felt obliged to be gory-esque, G-O-R-Y, because of that name.” “Nominative determinism,” the British writer Will Self calls it.16 No doubt, the body count is high in Gorey’s oeuvre. In his first published book, The Unstrung Harp, persons unknown may have drowned in the pond at Disshiver Cottage; in The Headless Bust, the last title published during his lifetime, “crocheted gloves and knitted socks” are found on the ominously named Stranglegurgle Rocks, leading the missing person’s relatives to suspect the worst.*

Bookended by this pair of fatalities, the deaths in Gorey’s hundred or so books include homicides, suicides, parricides, the dispatching of a big black bug with an even bigger rock, murder with malice aforethought, vehicular manslaughter, crimes of passion, a pious infant carried off by illness, a witch spirited away by the Devil, at least one instance of serial killing, and a ritual sacrifice (to an insect deity worshipped by man-size mantids, no less). In keeping with the author’s unshakable fatalism, there are Acts of God: in The Hapless Child, a luckless uncle is brained by falling masonry; in The Willowdale Handcar, Wobbling Rock flattens a picnicking family.

And, of course, infanticides abound: children, in Gorey stories, are an endangered species, beaten by drug fiends, catapulted into stagnant ponds, throttled by thugs, fated to die in Dickensian squalor, or swallowed whole by the Wuggly Ump, a galumphing creature with a crocodilian grin.

To relieve the tedium between murders, there are random acts of senseless violence and whimsical mishaps:

There was a young woman named Plunnery

Who rejoiced in the practice of gunnery,

Till one day unobservant,

She blew up a servant,

And was forced to retire to a nunnery.17

Only rarely, though, does Gorey stoop to slasher-movie clichés, and then only in early works such as The Fatal Lozenge, an abecedarium whose grim limericks cross nonsense verse with the Victorian true-crime gazette. Graphic violence is the exception in Gorey’s stories. He embraced an aesthetic of knowing glances furtively exchanged or of eyes averted altogether; of banal objects that, as clues at the scene of a crime, suddenly phosphoresce with meaning; of empty rooms noisy with psychic echoes, reverberations of things that happened there, which the house remembers even if its residents do not; of rustlings in the corridor late at night and conspiratorial whispers behind cocktail napkins—an aesthetic of the inscrutable, the ambiguous, the evasive, the oblique, the insinuated, the understated, the unspoken.

Gorey believed that the deepest, most mysterious things in life are ineffable, too slippery for the crude snares of word or image. To manage the Zen-like trick of expressing the inexpressible, he suggests, we must use poetry or, better yet, silence (and its visual equivalent, empty space) to step outside language or to allude to a world beyond it. With sinister tact, he leaves the gory details to our imaginations. For Gorey, discretion is the better part of horror.

The gory details: how he detested the phrase, not least because, year after dreary year, editors repurposed that shopworn pun as a headline for profiles but chiefly because it cast his sensibility as splatter-film shtick when in fact it was just the opposite—Victorian in its repression, British in its restraint, surrealist in its dream logic, gay in its arch wit, Asian in its attention to social undercurrents and its understanding of the eloquence of the unsaid.

Gorey was an ardent admirer of Chinese and Japanese aesthetics. “Classical Japanese literature concerns very much what is left out,” he noted, adding elsewhere that he liked “to work in that way, leaving things out, being very brief.”18 His use of haikulike compression—he thought of his little books as “Victorian novels all scrunched up”19—had partly to do with a philosophical critique of the limits of language, at once Taoist and Derridean. Taoist because the opening lines of the Tao Te Ching echo his thoughts on language: “The name that can be named / is not the eternal Name. / The unnamable is the eternally real.”20 Derridean because Gorey would have agreed, intuitively, with the French philosopher Jacques Derrida’s observations on the slipperiness of language and the indeterminacy of meaning.

Gorey believed in the mutability and the inscrutability of things and in the deceptiveness of appearances. “You are a noted macabre, of sorts,” an interviewer observed, prompting Gorey to reply, “It sort of annoys me to be stuck with that. I don’t think that’s what I do exactly. I know I do it, but what I’m really doing is something else entirely. It just looks like I’m doing that.”21 Pressed to explain what, exactly, he was doing, Gorey was characteristically evasive: “I don’t know what it is I’m doing; but it’s not that, despite all evidence to the contrary.”22

It’s the closest thing to a skeleton key he ever gave us. Apply it to his work, and you can hear the tumblers click. Take death, his all-consuming obsession. Or is it? Despite the lugubrious atmosphere and morbid wit of his art and writing, Gorey uses death to talk about its opposite, life. In his determinedly frivolous way, he’s asking deep questions: What’s the meaning of existence? Is there an order to things in a godless cosmos? Do we really have free will? Gorey once observed that his “mission in life” was “to make everybody as uneasy as possible, because that’s what the world is like”—as succinct a definition of the philosopher’s role as ever there was.23

Gorey inclined naturally toward the Taoist view that philosophical dualisms hang in interdependent, yin-yang balance. And while his innate suspicion of anything resembling cant and pretension would undoubtedly have produced a pained “Oh, gawd!” if he’d dipped into one of Derrida’s notoriously impenetrable books, he had more in common with the French philosopher than he knew. Derrida, too, questioned the notion of hierarchical oppositions, using the analytical method he called deconstruction to expose the fact that, within the closed system of language, the “superior” term in such philosophical pairs exists only in contrast to its “inferior” opposite, not in any absolute sense. Or, as the Tao Te Ching puts it, “When people see some things as beautiful, / other things become ugly. / When people see some things as good, / other things become bad.”24 Better yet, as Gorey put it: “I admire work that is neither one thing nor the other, really.”25

Revealingly, there’s an almost word-for-word echo, here, of the dismissive quip he tossed at the interviewer who asked him, point-blank, what his sexual preference was: “I’m neither one thing nor the other particularly.”26 The close harmony of these two answers invites the speculation that his aesthetic preference for things that aren’t either/or but rather both/and—as well as his fondness for ambiguity and indirection, puns and pseudonyms, and, most of all, mysteries—may have had personal roots.

“What I’m trying to say,” he told the journalist who pressed him on the question of his sexuality, “is that I am a person before I am anything else.”27 In the end, isn’t it a hobgoblin of little minds, this attempt to skewer a mercurial intelligence like Gorey’s on the pin of language? “Explaining something makes it go away,” he maintained. “Ideally, if anything were any good, it would be indescribable.”28

The paradoxical, yin-yang nature of the man and his art bedeviled critics’ attempts to sum up his sensibility in a glib one-liner, a point underscored by the train of oxymoronic catchphrases that trails behind Gorey. Writers trying to transfix that elusive thing, the Goreyesque, reach instinctively for phrases that conjoin like and unlike, describing his work as embodying “[the] comic macabre,” “morbid whimsy,” “the elusive whimsy of children’s nonsense … with the discreet charm of black comedy,” and “[the] whimsically macabre.”29 (Where would we be without the long-suffering “whimsy”?)

Gorey didn’t fit neatly into philosophical binaries: goth or Golden Girls fan? “Genuine eccentric” or (his words) “a bit of a put-on”?30 Unaffectedly who he was or, as he once confided, “not real at all, just a fake persona”?31 Commercial illustrator or fine artist? Children’s book author or confirmed pedophobe who found children “quite frequently not terribly likeable”?32

We can even see the quintessential Gorey look—Harvard scarf, immense fur coat, sneakers, and jeans, accessorized with a Victorian beard and a profusion of jewelry—as a sly rejoinder to black-or-white binaries, resolving Wildean aesthete and Harvardian, New York balletomane and Cape Cod beachcomber in an unnamable style that one journalist called “half bongo-drum beatnik, half fin-de-siècle dandy.”33 The effect, as the eye moves from the flowing white beard of a nineteenth-century litterateur to the elegant fur coat to land, anticlimactically, on scuffed white Keds, is a kind of sight gag—a goofy plunge from highbrow to low, with the sneakers as punch line.

Goths who knocked on Gorey’s door, in his semiretired final decade on Cape Cod, were crestfallen to be greeted not by a palely loitering Victorian in a Wildean fur coat but by an avuncular gent in a polo shirt and, during the summer, those mortifying short shorts old guys insist on wearing. Gorey refused to play to type: in his driveway, where you’d expect to find a decommissioned hearse, sat a cheery yellow Volkswagen Beetle and, later, a shockingly suburban Volkswagen Golf (though it was black, at least). Not for him the sinister suavity of Vincent Price or the open-casket affect of Morticia Addams; Gorey alternated between the languorous air of the aesthete, all world-weary sighs and theatrically aghast “Oh, dear”s, and a Midwestern affability born of his Chicago roots, most evident in the bobby-soxer slang that peppered his speech (“zippy,” “zingy,” “goody,” “jeepers”).

For an auteur of crosshatched horrors who collected postmortem photographs of Victorian children, Gorey was disappointingly normal. “His work and his personality [were] enormously separate from one another,” says Ken Morton, his first cousin once removed. “His day-today life was fairly frivolous and lazy and laid-back. It was watching Buffy the Vampire Slayer with a bunch of cats hanging on his shoulders and maybe reading a book at the same time or doing a crossword puzzle.”34

As Morton points out, Gorey’s everyday life wasn’t terribly Goreyesque. When he wasn’t hunched over his drawing board, he was cycling through routines so ritualized they verged on the obsessive. His virtually unbroken record of attendance at the New York City Ballet, from 1956 to 1979, is only the best known of his compulsions. “I’m a terrible creature of habit,” he admitted.35 “I do the same thing over and over and over and over. I tend to go to pieces if my routine is broken.”36

The routines that filled his days added up to an existence that, by his own avowal, was essentially “featureless.”37 Gorey was a bookworm. Waiting in line, killing time before the curtain went up at the ballet, even walking down the street, he went through life with his nose in a book. (His library, at the time of his death, comprised more than twenty-one thousand volumes.) He was a movie junkie, taking in as many as a thousand films a year. Of course, he spent countless hours lost in George Balanchine’s dances.

Not exactly the stuff of pulse-racing biography. This, after all, is the man who, when asked what his favorite journey was, replied, “Looking out the window”; who “never could understand why people always feel they love to climb up Mount Everest when you know it’s quite dangerous getting out of bed.”38 And if his uneventful life makes him an unlikely biographical subject, his tendency to snap shut, oyster-tight, when interviewers probed too deep makes him an especially uncooperative one. An only child, he was solitary by nature and single by choice. He had good friends, but whether he had any close friends is an open question. With rare exception, he was silent as a tomb on personal matters—his childhood, his parents, his love life. Even those who’d known him for decades doubted they truly knew him.

Gorey was inscrutable because he didn’t want to be scruted. He was a master of misdirection, adroit at dodging the direct question (about his art, his sexuality). His theatrical persona was part of that strategy of concealment. (Freddy English, a member of his Harvard circle, always felt that behind the Victorian beard, the flowing coats, and “the millions of rings,” Ted, as Gorey was known to his friends, was “a nice Midwestern boy” who “got himself done up in this drag.”)

In 1983, I came face-to-face with that persona. I was twenty-three, fresh out of college and newly arrived in New York, working as a clerk at the Gotham Book Mart. The store’s owner, Andreas Brown, was the architect of Gorey’s ascent to mainstream-cult status, publishing his books, mounting exhibitions of his illustrations, inking deals for merchandise based on his characters. Now and then, Gorey dropped by, usually to sign a limited edition of a newly published title. I was running down a book for a customer when a tall man with a beard worthy of Walt Whitman swept down the aisle. He was chattering away in a stage voice of almost self-parodic campiness, and his costume was equally outlandish, a traffic-stopping getup of Keds, rings on each finger, and clanking amulets, topped off with a floor-length fur coat dyed the radioactive yellow of Easter Peeps. Taking in this improbable apparition, I wondered who was inside the disguise.

This book is the answer to that question.

Gorey is grist for the biographer’s mill after all, not only because he was an artist of uncommon gifts but because he was a world-class eccentric to boot. If his life looked, from the outside, like an exercise in well-rutted routines, its inner truth recalls the universe as characterized by the biologist J. B. S. Haldane: not only queerer than we suppose but queerer than we can suppose.39 To be sure, he lived much of his life on the page, in the worlds he conjured up with pen and ink, and did most of his adventuring between his ears. In large part, the art is the life. But Gorey’s work also gives us a spyhole into his mind (as does his conversation and his correspondence).

And what a mind: poetic, playful, darkly nonsensical à la Lewis Carroll, exuberantly silly as Edward Lear, generally nonchalant but prone to melancholy in the sleepless watches of insomniac nights, surrealist, Taoist, Dadaist, mysterious, mercurial, giddy with leaps of logic and free-associated connections, rich in spontaneous insights, childlike in the unselfconsciousness of his pet peeves, hilarious in the self-contradicting capriciousness of his likes and dislikes. Gorey charms us by virtue of his inimitable Goreyness—the million little idiosyncrasies that made him who he was. And he was always who he was—utterly, unaffectedly himself; a species of one, like his character Figbash, or the Zote in The Utter Zoo, or better yet the Doubtful Guest, his enigmatic alter ego in the book of the same name, a furry, sneaker-shod enfant terrible who turns an Edwardian household upside down.

That’s as good a personification as any. Gorey was a dubious character, particularly in the eyes of children’s book publishers and Comstockian guardians of childhood innocence. But he was also doubtful in the sense that he was fraught with doubts: about his art (“To take my work seriously would be the height of folly”40), his fellow Homo sapiens (“I just don’t think humanity is the ultimate end”41), free will (“You never really choose anything. It’s all presented to you, and then you have alternatives”42), God, romantic love, language, the Meaning of Life, you name it. On occasion, he even doubted his own existence: “I’ve always had a rather strong sense of unreality. I feel other people exist in a way that I don’t.”43

Then, too, Gorey was a Doubtful Guest in the sense that he seemed as if he’d been born in the wrong time, maybe even on the wrong planet. By all accounts, he regarded the human condition with a kind of wry, anthropologist-from-Mars mixture of amusement and bemusement. “In one way I’ve never related to people or understood why they behave the way they do,” he confessed.44

How to get to the bottom of a man whose mind was intricate as Chinese boxes? In the pages to come, we’ll use the tools of psycho-biography to make sense of Gorey’s relationships with his absent father and smothering mother and of the lifelong effects of growing up an only child with a prodigious intellect (as measured by the numerous IQ tests he endured). Gay history, queer theory, and critical analyses of Wildean aestheticism and the sensibility of camp will be indispensable, too, in unraveling his tangled feelings about his sexuality, his stance vis-à-vis gay culture, and the “queerness” (or not) of his work. A familiarity with the ideas underpinning surrealism will help us unpack his art, and a close study of nonsense (as a literary genre) will shed light on his writing. An understanding of Balanchine, Borges, and Beckett will come in handy, as will an appreciation of Asian art and philosophy (especially Taoism), the visual eloquence of silent film, the mind-set of the Anglophile, and the psychology of the obsessive collector (not just of objects but of ideas and images, too).

Yet no matter how carefully we prowl the lawn for footprints or scour the Persian rug for bloodstains, like the sleuths in the Agatha Christie whodunits he loved so much, the Mystery of Edward St. John Gorey is, ultimately, uncrackable. “Each Gorey drawing and each Gorey tale is a mystery that ends—meaningfully—with the absence of meaning,” Thomas Curwen observed in the Los Angeles Times. “He would never presume to know, and if he did, he would never tell.”45 “Always be circumspect. Disdain explanation,” wrote Gorey in a postcard to Andreas Brown.46 The deeper we go into the hedge maze, the more stealthily we try the doorknobs in the rambling manor’s abandoned west wing, the more elusive he seems. Not that it matters: with Gorey, never getting there is half the fun.

* Publishers, dates of publication, and related details can be found, with a few exceptions, in “A Gorey Bibliography” at the end of this book. Quoted matter isn’t cited in endnotes for the simple reason that nearly all Gorey’s books are unpaginated; even so, readers shouldn’t have much trouble tracking down quotations, since few Gorey titles are longer than thirty pages.