Читать книгу The Full Ridiculous - Mark Lamprell - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

Most stories begin long before the point at which we choose to start telling them. You could have begun this story with…

I was born on the green vinyl seat of a two-tone Valiant;

or

I had never heard her utter a single syllable but when Wendy Weinstein spoke, she instantly sounded like home;

or

Wendy and I decided we were too young to have children so we adopted a cat.

But the most useful entry point to the story of your winter that began in summer and lasted one whole year occurs three days before you are run down by Frannie Prager’s blue Toyota.

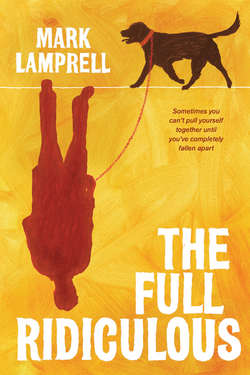

You remember most of that year like you never forget the squeal of nails down a blackboard. Some of it you’ve had to imagine, darn the holes between the facts to stitch together a proper story. But all of it, hand-on-your-heart, is the truest version you can offer. The full ridiculous.

It begins at Rosie’s school, where you are attending an information evening for the French tour. At the end of the year, Rosie and a group of her classmates will travel to Paris where they will practise and improve leur Français. Rosie’s school, Boomerang, is an institution from an era when people said gosh and gracious instead of shit and fuck; it reminds you of jolly adventures in a Girl’s Own Annual. You can’t afford it, but you and Wendy have taken out a second mortgage which the bank thinks is for home improvements but is actually to pay for school fees while you take a year off, researching and writing a book on Australian cinema.

Wendy works as the sales and marketing manager of a company that imports and exports high-end furnishing fabrics. She started as a part-timer when the kids were little and the flexible conditions meant she could pick Rosie up from pre-school or duck off when Declan got an award in assembly for Sitting Up Nicely When Mrs Donlan Is Speaking. With a degree in politics and history and a post-graduate diploma in conflict resolution, she only intended it to be temporary but quickly became indispensable and over a decade later she’s still there. The job is neither particularly well paid nor challenging (although the conflict-resolution training does come in handy wrangling flighty designers and belligerent sales reps). Wendy is prepared to ignore the drawbacks, at least while your children are at school, as long as it remains a family-tolerant corporate environment.

Her wage covers your mortgage and some living expenses but, because you are no longer on a salary, a black hole of debt widens before you. Your life savings are gone, courtesy of a sad little high-risk share portfolio masticated by the GFC, but you’re not too worried because your book is going to be a success and soon there will be champagne for everybody. Actually you’re not that dumb—you know this book might not make you rich—but if it’s successful there will be at least two more books: one on Russian cinema and one on German cinema. Eventually you plan a complete anthology of world cinema. You may be getting ahead of yourself but your gut tells you you’re going to be okay financially and sometimes you just have to listen to your gut, don’t you?

Don’t you?

Rosie’s trip to France is an expense you don’t need but it’s part of the deal at a school like Boomerang. Anyway, it’s almost a year away, which means you can hold it out like a carrot to coax her through the next few terms without any major disasters. Thus far, touch wood, this appears to be working.

Miss (not Ms) Crowden Clark (no hyphen), the French mistress, approaches the podium and gives the microphone a timid tap. Breathless with excitement, she welcomes the parents and expresses her joy at seeing such a fine turnout. You can tell it’s going to be a long night. You shift in your seat and stifle a yawn. Rosie leans over and whispers, ‘If you think this is boring, you should try her French classes.’ You share a smile and Rosie’s boyfriend, Juan, leans forward to catch what he’s missing out on.

Juan is living under your house in the single garage you converted into a rumpus room. He’s been kicked out of his own three-storey home, one floor of which was designed exclusively for him and his older sister. His parents adopted them both out of an orphanage in Buenos Aires when they were toddlers. Of African–Spanish lineage, Juan is handsome and dark and always being stopped by the police—a living echo of the dead rappers Rosie listens to so devotedly.

Your friends say you’re crazy letting him stay but he’s been nothing but polite and helpful and, while he remains so, he’s welcome. Your friends say they’re having sex and you know they could be but you believe Rosie when she says she’s going to wait until she’s sixteen, which is a bridge you’ll cross when you come to it. Your friends say she’s lying but it is not in her nature to lie. She may be wilful and defiant but she has always been alarmingly truthful—

Look Daddy, I’m flying out of the treehouse.

I’m just cutting Barbie’s legs to fit her in the box.

I’m only using petrol to light the fire.

Your niece Mel, who is thirteen years older than Rosie, says she’s the only child she has ever seen advance on an advancing adult; as you stride towards the three-year-old with your finger raised, she strides towards you, outraged that you would address her in such an impertinent manner. Once, when she was four, you smacked her for trying to cut off the cat’s tail and she followed you around for days showing you the red mark on her leg long after it had faded, repeating, ‘Look. Look what you done.’

While Miss Crowden Clark meanders into a monologue on the French roots of English words, you look around the restless prison of her audience hoping that someone has remembered to bring their poison darts. Rosie puts her hand up.

‘Yes, Rosie?’

‘Um, Miss, Ursula O’Brien hasn’t put her name down or anything but she was wondering if it’s too late to come.’

Later, in the car on the way home, you ask Rosie if this was a genuine question or a clever ploy to end Miss Crowden Clark’s ramblings. She rolls her adolescent eyes and looks out the window. You remember Wendy’s edict that driving is one of the few times you can dialogue with teenagers because they’re stuck in the car with you so you make a few stabs at conversation before Rosie snaps the radio on. Juan shrugs and grins at you in the rear-vision mirror and you doof-doof home.

And that’s it. An unremarkable evening appears to end uneventfully. Only it doesn’t. The evening may have ended but events have just begun. Something is happening. Rosie’s question to Miss Crowden Clark is setting off a chain reaction that will devastate you all.