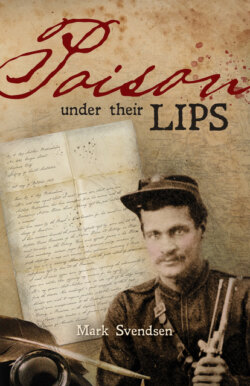

Читать книгу Poison Under Their Lips - Mark Svendsen - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

the disquietness of my heart

ОглавлениеNative Police Barracks,

Mistake Creek/Belyando District,

Dittley via Clermont,

Colony of Queensland.

15th March, 1876.

My only friend,

I have been witness to the most horrendous crime. My soul quakes before God at the barbarity I have seen. By my witness I am guilty also, as guilty as the perpetrators. But I am guilty of the greatest of all sins. I would not help my fellow man — despite his pleadings, despite the fact that I had it within my power to end the assault on him, despite the fact that it was a crime born of lust made terrible with malice, made coherent by madness, made desperate by the fear which fills this place — the fear of those who cannot belong. I am guilty and I am damned.

Who is there in this hell-hole to tell of my suffering? I cannot speak to the other white men. Many of them are as bad — though not all, by a long shot. If only I could find a priest to whom I could offer up my sins for redemption, but there are so few priests in this Godless land. To speak true, I have even stopped calling on our Lord in prayer. He has left this place to the white heathens. There is no one to turn to in my distress but you, my dear friend, my journal. Faithfully and honestly as I have tried to write you, how will I be able to tell even you of this cowardly attack?

I will take several deep breaths to still my heart, to clear my mind, to begin telling all, slowly and deliberately, from the beginning. If I stumble in the telling, please wait. I will rise up from the filth into which I have fallen. I will rise up because I must. I will rise up singing.

We had a quiet day in camp two days ago. The boys, as Lieutenant Wheeler calls them, had various jobs to complete — restuffing saddles, sewing buckles to girths, replacing reins on the metal bits, plaiting greenhide thongs — all the small but necessary jobs bushmen must catch up with after an expedition.

Trooper Toby had set himself up on the lean-to verandah of the Troopers’ quarters where he inspected all the work which the other boys completed. He then hung up the stirrups and girths and greenhide rope in an ordered collection on pegs fashioned from forked tree branches, which he had fixed to the wall of the slab hut.

Trooper Toby is the oldest of the boys. He has served the longest with the Native Police, but he is not of higher rank, as all six of the black-fellows with our patrol, including the special trackers, are indistinguishable in that regard — all are simply Troopers. Toby grunted when one of the boys presented him with some well-finished work, but spat nikki-nikki juice and derision when the work did not meet with his approval. The boys were scared of him and he was content to keep them that way. If he spat at one of them they grabbed their work and scuttled back to their place under the shady wattle trees to busy themselves in fault fixing. The other boys would smile secretly, thinking themselves lucky they were not singled out. They never laughed aloud though — such action would tempt fate and draw Toby’s ire to them.

We have been on the road for several weeks to get here and will be leaving again for patrol the day after tomorrow, this time to the Southern districts. The Lieutenant is very keen to go. I expect, if the horses were not in such desperate need of rest and feed, he would have turned us out again after only one night at the Barracks here in Belyando.

‘Barracks’ is probably too grand a word for our accommodation here but, as we are in the Police Force, I suspect it is the word the Force would use, even if we were living in canvas tents.

I could see the entire Barracks and its activities from the doorway of the smallest of the three huts which comprise the police compound. This abode I share with the Sergeant. How I wish that if circumstances had proved different I could share such a humble dwelling with my dearest Eurydice ...

Our hut is furnished with the small explorer’s table at which I now write — a present from Father on my departure from ‘Elysium’ — and a rough bush bunk at either end. A large slab window, hinged at the top, is propped open to its fullest extent with a stick. Despite the flow of air, today is as humid as any I have encountered in my short stay in this central part of the Queensland colony. Even the usual relative cool of Mistake Creek, not so many yards distant, seems heated to a vapour under the steaming sun. It is this brutal humidity, I am sure, that forces so many to live no better than beasts, though I cannot — will not — excuse the actions of us all later, on the night which I now recount for you.

I had moved my table to the centre of the doorway to catch any breeze which flopped past in the afternoon. We all hoped fervently for a storm. The boys were all shirtless, with bare feet — only trousers providing a modicum of decency.

The Lieutenant allowed them the pleasure of semi-nakedness only in camp. The Sergeant and I were required to be dressed in full uniform at all times. The boys yabbered to each other in pidgin English, laughing and chiding one another in their child-like manner. A scene of contentment, for now.

Sergeant Thomas called us to luncheon in his quaint way,

‘Up for it now, boyos, and no shananaking!’ It was a rare, welcome delight to eat at noon, as our lot whilst travelling was breakfast and dinner at best, at worst just one meal a day. It was a sure sign the Sergeant was happy, for when he was so, he enjoyed preparing a meal. Wheeler joined us to eat, then issued orders for us to go back to our duties while he retired to his hut to sleep off his repast.

Sergeant Thomas continued in the hot, heavy work of re-fashioning and fitting shoes to all the horses, as they were well in need of the work and Lieutenant Wheeler would not hear of the expense of having a proper blacksmith do the job in a proper smithy in Clermont, only some forty-five miles distant. As he put it, ‘... we have our own proper little Welsh Taffy here to do it for us.’ This was how he referred to our Sergeant.

I was sitting all day, ordered to settle the accounts and prepare correspondence and reports concerning the state of our small contingent. This work was the commanding officer’s duty and sole responsibility, not mine. I was well aware that the Lieutenant provided forged receipts from smiths and other businesses for work and goods which were never provided by them. Instead, when reimbursement for expenses was remitted he would ensure his little rum keg was full and gin and brandy put by. While I did not enjoy the paperwork, it was lying to the Colonial Government, and thereby to Queen Victoria, which I found most difficult.

When I raised this matter with the Lieutenant he laughed and said, ‘You are in the Native Police now, boy, and in the Queensland bush the Native Police is all the law you need to know and all you require.’

I need not remind you, my friend, I am barely eighteen. Had I reached my majority I should have taken stern action against such outrageous swindling. Bring on my twenty-first year, though by then, I fear what sort of man I may have become.

A thought just startled me. I have not at any time, not once since we left Brisbane, formally introduced you to all our Troopers. How poor a host! They have shared my life and my latest trial, and I've not had the courtesy to even name them.

Other than Toby and Dicky-Dicky, we have Dicky — just to confuse the issue I am sure — Cain, Patrick and Georgy. Cain is the quietest of the group, almost painfully shy. If I were to play favourites, which of course an officer may not, Cain would be my choice for a friend. I believe he is much like me. All the other boys are far more forward and frolicsome. Their lively joy reminds me constantly of my beloved Eurydice. Notwithstanding this fact, however, they are a Troop of the highest mettle and a surprisingly companionable group.

I remember well that by mid-afternoon Patrick and Georgy began arguing about some trivial thing and I was immediately reminded of Mother, Father and James, so far away if I count the miles, though always so close in my thoughts. I closed my eyes and was instantaneously transported in imagination back to the front hall at ‘Elysium’, where James and I had brought some minor quarrel between us indoors after an outing across the farms.

How Mother and Father both had stood, carefully questioning us as to our opinions in the matter. Then, after hearing us out, Father gave his deliberation. We remonstrated, of course, but Mother said, ‘Be content. Your Father has spoken.’

Then she told us to apologize to each other, ‘...as though you mean it.’ I smile now to think how both James and I knew from long training what would happen next. How we objected with horribly drawn faces, even before the dreaded directive. Mother ordered both of us, ‘Now kiss your brother!’ What grim, disdainful lips we puckered toward each other in offering of forgiveness. ‘You have quarrelled and now you have made up,’ Mother said. ‘That means it must be tea time!’ Oh Mother! Oh Father! How easy it all seemed then. How little my brother had to forgive me. How unresolvable my case seems now.

While I didn’t enjoy the Lieutenant’s paperwork, especially the copying of letters and reports, I did not complain as the breeze picked up during the afternoon and it grew cooler. Listening to Sergeant Thomas’ heavy work — the smack of the hammer against the anvil, or the serpent’s hiss of the red-hot iron dipped in the cooling barrel, or even the draughty breath of the small bellows Trooper Patrick used to fan the open furnace fire — I was happily resigned to my lot. It seems to me now that my intervention, which broke the contented mood of the afternoon, was a forewarning of a chain of events which would end so badly.

At approximately 3.30 o’clock I called out to Toby to put on the pint pot for a cup of tea. He, of course, straight away ordered up Trooper Dicky-Dicky to organize the necessaries.

By 4 o’clock we were all sharing a cup of char on Toby’s verandah. As I went to sit down I was affrighted by a large huntsman spider springing toward me from the leaves at my feet, causing me to spill all my tea before I managed to kill the creature with my pannikin. The boys thought this great fun, mimicking in turn my wide-eyed discomfiture. I decided that, if I looked half as comical as they, all white eyes rolling, I could not begrudge their laughter, so I joined together with them. Perhaps by way of an apology, they asked me to sing a song. The natives love to sing and dance and I am sure I am not immodest in suggesting my good, strong voice is a pleasure for them to hear. For some reason I had little need to think for long about which song to choose.

Perhaps it was that I had been daydreaming of Mother at home in Adelaide. Whenever I have done so, since being here in the wilderness, I have always remembered, with both awe and comfort, our visits to our local church for mass. Or perhaps it was the appropriateness of the words to my situation here.

I sang the 23rd Psalm to their rapt attention then, by way of contrast, the old folk tune, ‘Little Brown Jug’. The boys all joined in the chorus, haa, haa, haaing away with great gusto.

The Lieutenant did not join us, but raised himself enough without leaving his cot to command Toby to bring him some tea to put with his tot of rum and to abuse us soundly for disturbing his sleep. Toby sent Trooper Dicky over to him with a pannikin of char as we all dispersed.

Psalm 23

(King James Bible)

The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.

He maketh me to lie down in green pastures:

he leadeth me beside the still waters.

He restoreth my soul:

he leadeth me in the paths of righteousness for his name’s sake.

Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,

I will feel no evil:

for thou art with me;

thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.

Thou preparest a table before me in

the presence of mine enemies:

thou anointest my head with oil;

my cup runneth over.

Surely goodness and mercy shall

follow me all the days of my life:

and I will live in the house of the

Lord for ever.

Why is it, my dearest friend, though my candle is now burnt down to half its size, that I have still not begun to tell you properly what has occurred? What monstrous fact prevents me? What is this thing that crouches, smothering the truth under its shroud of night? I see a figure, tall, hooded and caped in a cloak of utter darkness. He has flung his mantle around the only light, the words that illuminate my innermost confessions. Oh my dearest, dearest friend, not even here in my journal can the truth yet be seen. Not even here in my written heart. And yet it must be. I must will it to be. I beg you wait and I swear I will rise up to wrest the truth from darkness.

It was possibly as late as 6.30 o’clock when a horseman rode into the Barracks. We recognized him immediately as Sergeant Connor from Clermont. Our Sergeant and I both called to him our welcome and an invitation to join us for the night. No sooner had we suggested this than the Lieutenant appeared, somewhat unsteadily, at the entrance of his quarters. He called to Connor to stay with us for the evening, as it was already almost dark and there were too many niggers down in the camp (half a mile distant from our own) for him to be safe riding home at night.

Besides, he added, as we were just back from Brisbane and would be setting out again all too soon, and we had a guest, it was time for a party.

It is likely that it was only the habit of years of command that made his offer sound so much like he was ordering our visitor to stay. I cannot imagine Father ordering his guests in so disrespectful a voice, and I believe such a tone offends against hospitality.

Sergeant Connor took no such umbrage however. Perhaps he was used to unthinkingly obeying orders? He readily agreed to stay for a night he would long remember. The boys were ordered out into the dying light to collect wood for a bonfire in the centre of the Barracks yard. We three, at Wheeler’s ‘invitation’, shared in his bottle of rum.

Soon Toby had finished cooking up a fine salt-mutton stew with taters and cabbage palm tops, which we followed with damper and treacle by way of dessert. The Lieutenant was most pleased and ordered a firkin of small beer to be tapped for the boys and a bottle of gin for the officers. From then on the party progressed merrily, with our blacks providing the entertainment.

The good food contented our bodies and the grog raised our spirits. How well I now understand those many sermons I have endured on the evils of the drink.

The boys, being unused to strong liquor, began hilariously re-enacting scenes from their day. They played out a scene before us in which each of them in turn would take their handiwork up to Toby for ‘inspection’. (Trooper Patrick played Toby’s part in their little pantomime.) Each time they did so, his expression of contempt grew more and more outrageous, to the delight of the audience, until the real Toby could stand it no longer and chased the actor into the darkness, all the while threatening to ‘bin fix ‘im proper!’ Toby was egged on in his pursuit by the Lieutenant, who was much further under the weather than the rest of us, having begun his tippling early.

For the first few months with our Troop, initially in Brisbane then here, I have attempted, as you well know, to abstain as far as possible from taking liquor, much to the disgust of our ‘esteemed’ leader, but I was loath to take what I’ve so often heard the preachers describe as ‘the slippery path to damnation’. Little by little, in this Godless wilderness, with nothing but blacks for company, the grog has begun to offer the only comfort I have known. If only I had heeded the advice of my betters. But I digress again. I must keep my hand to the heart of this story. I must share with you its bitter end.

When Toby returned from his mock battle with Patrick, the Lieutenant, deciding that he was not amused enough by the evening, ordered him to go down to the blacks’ camp and see if he could organize any entertainment. ‘Take Patrick for company,’ he added sardonically. It obviously amused him to see the chagrin on Toby’s face, as there was no reason for anyone to accompany him.

They left, with Patrick dragging a goodly, safe distance behind. In their absence the boys insisted on singing their version of ‘Little Brown Jug’, urged on by Wheeler and our Sergeant. Our visitor remained silent. By this time I was becoming quite groggy and spin-headed with the drink, so I excused myself and retired, unsteadily, to my bunk, accompanied by a brow-beating from the Lieutenant on my weakness. Outside the party continued unabated, but I fell almost instantly into a drunken sleep.

Little Brown Jug

(Traditional folk song)

My wife and I live all alone,

In a little bark hut we call our own.

She loves gin and I love rum,

I tell you, don’t we have some fun!

Ha, ha, ha! You and me,

Little Brown Jug, don’t I love thee!

(repeat)

My wife and I live all alone,

In a little bark hut we call our own.

She loves rum and I love gins,

I tell you, don’t we make some sins!

Ha, ha, ha! You and me,

Little Brown Jug, don’t I love thee!

(repeat)

I awoke with a start to the sound of women screaming and the hoarse oaths of men. Waking from a deep sleep, I could not readily tell the time, except by the fact that the fire had burned down to a mass of smouldering coals. The screams sent a dread shiver through my body. Immediately alert and sobered, I jumped up from my bunk and hastened to the Troopers’ Barracks, from which the blood-curdling noise issued.

Imagine my distress, dearest friend, at the sight that greeted me. On the verandah I could see, quite clearly in the light of the still-glowing fire, the entire party gathered, except for Sergeant Connor. The Lieutenant and Sergeant Thomas were swearing and arguing with two women, restraining them physically as they shrieked and yabbered like monkeys. Two of our boys held between them an equally violent black boy of about twenty years. He was a stranger to me. Wheeler called him Jemmy.

I ran toward the scene, but when no more than five yards distant I was brought up to a dead halt. One of the women was my Eurydice. I was dumbfounded as she stood there, imploring, struggling against her captors. My beloved dusky virgin of the bush. How often have I confided in you, my dear friend, throughout our arduous journey to this place, my love for her, a love I could never confess to family, nor to any in this hateful place. How devastated she looked, held captive by that man, my Commander, her hair full of twigs, her dress torn asunder, blood on her face and below.

Sensing my presence, Eurydice and Wheeler both turned to me at once. Wheeler’s face was contorted, twisted in a leer of fury. My Eurydice, recognizing me, lost the last tatter of her self-possession. Her face was shocked and devastated.

Without her human dignity she was the instrument of the brutal lust of beasts. My heart was destroyed by that gaze. My mind became a blood-red fog of revenge.

I accused Wheeler with a stare, questioning him with my look as to what was happening. I thought, at that moment, that he would burst before my accusation in a paroxysm of fury — but a shadow of control passed over him as a cloud in the night. Still holding tightly to Eurydice, he thrust her toward me. The entire company waited in silence. Only the other woman could be heard sobbing fit to break.

‘Look at her!’ he screamed, pushing her toward me — a naked, dishevelled mess. ‘Look at her!’ he commanded.

Oh, my very faintest God, I looked!

‘It was him!’ Wheeler screamed, whipping his hand to point toward the strange black boy, Jemmy. ‘He is responsible for this outrage against her! That savage has raped her.’

I stood still, dumb-struck by darkness. Unable to move, let alone speak, I stared at the accused. My beloved had been taken by that nigger against her will. I staggered on my feet as if struck a physical blow. I looked back to Eurydice. My friend, her face was utter, void despair.

‘He must be punished.’ It was Wheeler’s voice, disembodied as a spirit in the ether, as sometimes I am sure I can hear the voice of my Mother call to me. (Oh, Mother, where were you when I needed your courage?) So much I wished to go to Eurydice, to offer her even the least of human compassion — to touch, to hold, to hide. But I could not, not before the men, not before Wheeler, not here, not now. Instead, to my shame, I turned away as I saw Wheeler nod his head and heard the first blow fall. I heard the women begin to wail hysterically again, whereupon they were roughly pushed inside the Barracks hut. I turned back at that sound, unable to control my actions.

‘Let them go,’ I screamed at Wheeler, grabbing him hard by the arms as he struggled against me. ‘They’ve done nothing!’ He hesitated, eyes glazed, staring at me, his mouth flecked with spittle like a rabid dog. Had anyone ever challenged his orders before? In my moment of anger I doubted it. For what seemed an eternity Wheeler did not answer. Our chests heaved with our voiceless contention. He broke from my grasp.

‘Yes, boy,’ he answered, controlling himself just enough to rein his madness in. A white-lipped snake’s smile split his mouth, ‘We may have had enough amusement tonight.’ He paused. ‘There’s work to be done and you will have a hand in it.’

I moved to remonstrate but he pushed me heavily away from him. The moment of confrontation was past.

Eurydice and her black sister were herded away from the Barracks, but they did not go far. Holding each other, they huddled just beyond the firelight. The blackboy Jemmy was handcuffed around the ankles and the clothes stripped from his body. As they so humiliated him Jemmy fought with his captors like a native cat, but there were too many of them. At Wheeler’s command, our boys fastened another pair of handcuffs to his wrists.

They took down a greenhide strap from its peg on the wall and fastened it to the handcuffs. Then they began to tie him to the rafter that hung out from the end of the verandah. Before they could accomplish their aim, however, he slipped and fell to the ground. The Lieutenant kicked him as he lay, three times hard in the stomach his boots thudding into the body with the sound of a mattock into rich, moist earth. In my mind I hear that sound yet.

My Eurydice cried out when Jemmy was kicked, and the boy answered her urgently, gasping out in his own tongue. I turned towards her, but Wheeler barked out an order,

‘Let’s see how you deal with a rapist, Wilbraham. It’s time you started your proper training.’ He grabbed my shoulder, urging me on. ‘Show this filthy dog what to expect from the Queensland Native Police.’

Eurydice turned away to run, screaming one final word in her gibberish before she disappeared. All I could see in my mind’s eye was the image of her devastated face. I ran to the black where he lay and put my boot, with all my effort, into his back, cracking ribs — again and again and again. It was Wheeler who restrained me, saying, ‘Steady on, boy! Don’t hurt him too much. The night is just begun.’

I turned away and caught sight of Eurydice, come back again into the circle of firelight. Her face was changed now. Her expression was one of unbearable bewilderment and, strangely, so strangely it seems to me now, she seemed completely alone.

Regina v. Wheeler. Committal Hearing Deposition:

When Jemmy was tied to the Rafters, one of the boys were told to flog him. I cannot remember which one. Jemmy was well able to stand on the ground. His hands were above his head. The Trooper flogged him with a stockwhip and gave him eight or nine blows on the back. The whip was like the handle of a small, light Teamster’s Whip (about 4 feet 6 in long) without the lash. The small end tapers and it is possible the whip was made of cane that was covered with brown paper and green hide lashed over all. The Boy was naked at this time. Another Trooper was told to flog Jemmy afterward by Mr Wheeler. He flogged him. He gave Jemmy about a dozen blows when the whip broke. I then saw Mr Wheeler flog the boy with a leather girth taken from a peg on the barracks wall (Exhibit A). That now shown me is the same and it is in the same state now as when it was used. Mr Wheeler struck the boy with that half a dozen or a dozen times with the Strand ends. Mr Wheeler then called on a native Trooper named Toby and he flogged him ten or a dozen times. I cannot say whether it was with the broken whip or with the weapon (Exhibit A) now before the Court. After that Mr Wheeler gave him a few more blows, I think with Exhibit A, as I remember seeing the strands fly around and hit Mr Wheeler’s hand. I told Mr Wheeler, ‘That will do, Sir, I think the boy has had sufficient.’ Mr Wheeler replied, ‘That hasn’t hurt him,’ or words to that effect. After that he told another Trooper to flog him again. The Trooper did so. I believe it was with the Exhibit A. There was nothing else to use then. That Trooper gave a dozen or a few more blows. I again said to Mr Wheeler, ‘That will do, Sir. This boy has had enough.’ He and the Troopers then untied the boy and he was taken back to the Troopers’ Barracks. lt was faint moonlight at the time.

Arthur Bootle Wilbraham, Cadet Officer,

Qld Native Mounted Police.

Taken and sworn before us at Clermont,

this 30th day of April 1876.

Geo. Murray, Presiding Magistrate

Now you see how damned I am. Even to you, my dearest and closest friend, I began with a lie and the lie would have continued, until it became the only truth, if I had not willed the story from myself. Please forgive me, but as I am a Christian man, I swear this is finally a true and accurate account of the matter. There is a commotion at the door now which must be serious as the hour is very late. I must go, but will report to you post-haste of the news as it comes...

For now,

Arthur

Postscript: A shadow has veiled the sun. I swear to you it was not meant to come to this pass. I swear, as I heard the news so recently imparted to me, God shrivelled in my chest. I swear the punishment we meted out to that rapist was rightful, not harsh nor unjust. I write the news I have promised, though it blackens me to Hell. Trooper Patrick has just informed me that, despite being removed from here back to Dittley Station in fair health two days hence, the black boy Jemmy has died from the injuries of his beating. I am visited, not by Patrick, but by the angel of despair.

Eurydice, now this. What will I confide to you next, my sickened friend? I am damned, though I must continue with my melancholy duty.

But Eurydice, where have you gone?

The Capricornian,

Rockhampton.

10th June, 1876

From a private letter received from the Aramac, we learn that another alleged case of flogging to death, at the Mount Cornish Police Barracks, has been reported to the Aramac police. In this case the blackfellow was tied to a tree and flogged to death with fencing wire. This report should be sifted thoroughly and immediately or the central and western districts of Queensland will get a rather unenviable notoriety in that respect.