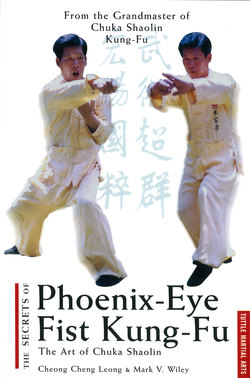

Читать книгу Secrets of Phoenix Eye Fist Kung Fu - Mark Wiley - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPart I

Chuka Shaolin in Perspective

CHAPTER ONE

Historical Perspective

The historical documentation of a fighting art that spans several hundred years is a difficult undertaking. This is especially so when the art in question lacks written documentation prior to the 1970s, as is the case with Chuka Shaolin. And while Cheong Cheng Leong knows the history of his art as passed on to him by his late master, Lee Siong Pheow, he is unsure of the origins of the art past five generations.

In an attempt to be as accurate and as detailed as possible, we not only present the oral history of Chuka Shaolin as passed down through the generations, but we also offer several new insights into the “mother art(s)” from which it may have sprung.

One possible origin of Chuka Shaolin is found among the Hakka, or Guest Family, peoples of Canton/Guangdong, China. There is a martial art among the Hakka people that stems from Chu gar kow, or the Chu family religion. Chu gar kow was originally an underground society that formed during the Qing/Manchu dynasties. Chu gar kow’s fighting art is now known to many as Chu-gar mantis, the first of the “southern” praying mantis systems to have developed. Over the years, other styles of southern mantis, such as Chow-gar and jook lum have also evolved. Since the Chinese characters for Chu-gar (southern praying mantis) and Chuka (phoenix-eye fist) are the same, it is possible that the latter art evolved from the former.

Another possible origin of Chuka Shaolin is Fukien white crane boxing. Some believe that the teachings of the Chu gar kow spread and became the various styles of Fukien Shaolin boxing—of which white crane boxing is a part. Since the cave where the nun Leow Fah Shih Koo resided and later taught her “Shaolin” art to the Chu sisters was known as the Pai-Ho Toong, or White Crane Cave, it is possible that Chuka Shaolin is based in pai-ho, or southern white crane, kung-fu.

Perhaps a more feasible explanation is that the art evolved as an eclectic blend of several Fukien Shaolin arts, including white crane boxing and Chu-gar praying mantis boxing.

However, like so many other martial arts, the history of Chuka Shaolin is shrouded in the myths and legends of oral traditions passed down through the generations from master to disciple. In the case of the art in question, oral history holds that it was founded by a Shaolin nun who, after leaving the Shaolin Temple, passed on her art to two sisters with the surname Chu.

The story goes something like this...

A Nun and Two Sisters

In the late eighteenth century, there was a Buddhist nun named Leow Fah Shih Koo who was said to have attained mastery of Shaolin kung-fu at China’s Fukien Shaolin Temple. She learned the art from her brother, Abbot Chih Sun. During a time of political turmoil, Leow left Shaolin to seek a more peaceful and quite life for herself in the Pai-Ho Toong, or White Crane Cave, in Kwangtung province.

Aside from her skills in Shaolin kung-fu, Leow was also an herbalist. In fact, she earned her living by gathering and compounding herbs from the hillsides and selling them in a nearby town.

One day, while en route to town to sell her herbs, Leow chanced upon two sisters who had been abandoned and left to fend for themselves in the village granary. Upon further investigation, Leow found that the sisters were Chu Meow Eng and Chu Meow Luan, daughters of wealthy parents who had recently been robbed and murdered.

Leow took the children into her cave-home and raised them as her own. The Chu sisters assisted the nun in the collection of herbs and the preparation of compounds for sale in the village. In addition, Leow taught them Shaolin kung-fu, an art at which they excelled. In fact, it is said that the Chu sisters were so talented that they were able to master the Shaolin art after just a few years of dedicated practice. It was upon their completion of Shaolin training that Leow encouraged them to study the fighting instincts and techniques of animals and insects. With this in mind, the Chu sisters then embarked on observing and imitating the fighting actions of the praying mantis, tiger, monkey, and snake. They then incorporated these new skills into the Shaolin art taught to them by Leow. Elements of the praying mantis, tiger, monkey, and snake can be found in varying degrees in the empty-hand forms of this dynamic fighting art.

After perfecting their new fighting art, the Chu sisters presented it to the nun for review and criticism. Leow was so impressed that she formally named the new art “Chuka” from Chu, the sisters’ surname, and ka, meaning “family” in the Hakka dialect. Thus, Chuka refers to the Chu-family style of Chinese martial arts. And while not a Shaolin martial art proper, and actually having developed independent of the temple itself, in deference to the Fukien Shaolin Temple wherein Leow learned her fighting art, the name was carried over. Thus, the complete name of the Chu sisters’ art became Chuka Shaolin.

It was also during this time that the nun envisioned and came to develop the deadly hand-formation resembling the eye of the mythical phoenix. Feeling that this particular fist strike was especially effective for women (i.e., herself and the Chu sisters), Leow incorporated it into the Chu sisters’ new fighting art. As time passed, however, the exponents of Chuka Shaolin began to favor the use of the phoenix-eye fist hand strike. As a result, the art of Chuka Shaolin is now more commonly known as phoenix-eye fist kung-fu.

OOH PING KWANG

After Leow passed away, the Chu sisters embraced her kind disposition and continued to gather herbs, make medicinal compounds, and practice kung-fu. One day while on their way to town, one of the sisters was accidentally struck by mud thrown by a group of boys who were fighting. Upon seeing that a passerby had been struck with the mud, all the boys fled, with the exception of the one who had actually flung the mud. The boy apologized profusely for the accident, stating that he was merely flinging mud in all directions so as to keep the bullies from getting at him.

The boy’s name was Ooh Ping Kwang. He was an orphan who tended the cows and did other chores on his uncle’s farm in exchange for his keep. The sisters were so impressed with the boy’s disposition and honesty that they approached Ooh’s uncle and asked permission to look after the boy. The sympathetic uncle said he would consent only if the sisters agreed to teach his nephew their martial art in an effort to secure a safer future for the frail child. The nuns agreed. Ooh was nine years old at the time.

Over the many years Ooh served the Chu sisters he grew to manhood and became quite skilled as a martial artist and as an herbalist. On the death of the second Chu sister, Ooh, now almost forty, descended from his cave-home and settled in the village, where he married a local girl. Ooh then set about imparting the Chuka art and herbal knowledge to his relatives and trusted friends, never forgetting the Chu sisters, their strict teachings, and their high moral character.

LEE SIONG PHEOW

Lee Siong Pheow (1886-1961) was one of Ooh’s most gifted disciples. He was trained in a more rigorous manner than any of Ooh’s other pupils, serving a long apprenticeship with the master. Lee worked hard during the day, fully occupied with the domestic chores in his master’s household. Every evening and early each morning Ooh directed Lee’s Chuka training. Lee was required to undergo unremitting practice of the various stances and postures, an unnerving and boring practice to be sure, but he persevered. Lee’s only problem was his temper. While he willingly accepted the hard work and the beatings administered by his master, and whatever harsh punishment the master might decree to correct any mistakes made in training, Lee could not accept domination by others.

One day, Lee’s temper got the better of him. He relentlessly beat Master Ooh’s son during training. For this unforgivable act, Master Ooh, using a long hardwood pole, fiercely struck Lee’s fist and foot, crippling the index finger of his right hand and deforming one of his feet for life. While such a severe lesson would surely have discouraged a spiritually weaker man, it only served to make Lee realize that his skill was not yet perfect. He had to train even harder than in the past. In time, Lee’s diligent effort and consistent training elevated him to the highest level of Chuka Shaolin excellence, and it is said that no local fighter could defeat him in one-on-one combat.

In 1930, Lee left Kwangtung and emigrated to Malaysia, where he settled in Penang and earned his living as an herbalist and traditional physician (fig. 1). He followed the strict traditional policies of his Chuka predecessors, especially the rule of choosing students with wisdom and great care. Lee required that each candidate who wished to study under him accept certain conditions. The candidate was to kneel before him holding a cup of Chinese tea in one hand and a small red envelope containing money in the other. By this method, Lee tested the candidate’s humility and sincerity. Many refused to kneel before the master, instead issuing pompous challenges of fighting skill. Lee, a man said to have never refused a challenge, obliged. As in China, Lee was never known to have been defeated in Malaysia. Many, after being defeated and thoroughly embarrassed at the hands of Master Lee, had an immediate change of heart and, in the manner Lee required, asked to be accepted as a student. Once accepted as a pupil, Lee inculcated them with three principles:

• Do not create or seek trouble.

• Do not teach people of unproved character what you have learned.

• Always be humble and respectful to others.

Indeed, a breach of any of these principles meant instant expulsion from the art. Master Lee was said to have never given an offender a second chance.

Master Lee passed away in 1961, at the age of seventy-seven. His most prized pupil was Cheong Cheng Leong, the current grandmaster of the art.

Lee Siong Pheow

CHEONG CHENG LEONG

Cheong Cheng Leong began his study of Chuka Shaolin under the tutelage of Master Lee Siong Pheow in 1951, at the impressionable age of ten (eleven, by the Chinese calendar). Master Lee, who was already in his sixties at this time, was famous in the Air Itam quarter of Pulau Pinang, Malaysia. Someone had told Cheong that there was a master in the town who knew a very special type of fist that was strong and could surely kill anybody, regardless of size and fighting ability. Being a young and impressionable boy who liked to fight, Cheong approached the master, determined to learn his art (fig. 2). At that time, Lee taught only Chinese of Cantonese or Hakka status, no Hokkien. Fortunately for the future of the art, Cheong Cheng Leong was a member of the correct social class.

Cheong Cheng Leong

Master Lee was interested in Cheong and his friends because they were so young and impressionable; he believed that he could mold them into respectable and upstanding citizens. When he approached Lee, the master asked Cheong if he was interested in learning Chuka Shaolin to become a better fighter. Cheong answered no, he was not interested in the art for fighting. Master Lee then asked the young Cheong why, if not for fighting, he wished to learn kung-fu. Cheong sat there in silence. Master Lee again asked Cheong if he was sincerely not interested in the art for purposes of fighting. Cheong replied that he was really not interested in such things. With that, Master Lee seemed content and said since Cheong was not interested in fighting, he would accept the boy as a student.

Master Lee still adhered to the ceremony of accepting new pupils, but Cheong was young and forgot all that was expected of him in this regard. He simply stuffed five Malaysian dollars into a red envelope and handed it to the master. At that time, five Malaysian dollars was quite expensive for kung-fu training in Malaysia. After all, one could join any of the other martial arts associations in Penang, like Chin Wu, for only one or two dollars. However, money seemed no object for some, and a few people who could afford it paid Master Lee fifty Malaysian dollars for lessons! These people thought that with the extra money changing hands, they were afforded special attention and training by the master. Cheong, however, is of the opinion that they learned nothing special as a result.

Cheong and his friends used to hang out and fight on the banks of the Air Itam river—nice water, nice fishing, nice fighting. For despite what he had told Master Lee, he actually wanted to learn martial arts to become a better fighter. From day one of his practice, Cheong was already plotting ways in which to use the new techniques in a fight. A few months after beginning his Chuka training, Cheong and some of his Chuka classmates had a fight with a group of boys who were saying derogatory things about the fighting art of Master Lee. Though in their minds they had an acceptable reason to fight, Master Lee scolded Cheong and his classmates and warned that if they fought again, under any circumstance, he would expel them from the school. The art and guidance of Master Lee truly changed Cheong’s character, and he has not fought since.

Master Lee’s Chuka Shaolin classes were held in his backyard, within easy walking distance from Cheong’s home (fig 3). Classes were held seven days a week in the morning, afternoon, and evening, and each session lasted roughly two hours. Cheong was quite studious and incorrigible when it came to training. In the beginning, he trained in all three classes on each day of each week. After three or four years of consistent training, Cheong no longer had to pay the student training fee, for he became Master Lee’s assistant.

Master Lee Siong Pheow died in 1961; he was seventy-seven years old. After the master’s death, his disciples held a formal meeting to discuss the future of Chuka Shaolin. During this meeting one of the disciples nominated Cheong to succeed Lee as the head of the art, since it was Cheong who had learned the most from their late teacher. It was unanimously agreed. From then on, even Cheong’s seniors would come to him for pointers or to learn a new technique or form.

Lee Siong Pheow (seated) with his students.

Prior to Lee’s passing, Cheong had never entertained the thought of teaching kung-fu for a living, and certainly not on a commercial basis. However, in 1964, with the encouragement of many people, Cheong decided to open classes in an effort to keep the art from becoming lost.

In the 1970s, Cheong opened a clothing, souvenir, and gift shop that caters to the many tourists who trek up the long stairway to the great Kwan Yin statue at the Kek Lok Si Temple, located in the Air Itam quarter of Pulau Pinang (fig. 4). After business hours, the shops and stairs empty and students gather to practice the art of Chuka Shaolin on a section of flat stone running parallel to Cheong’s shop (figs. 5, 6).

CHUKA SHAOLIN TODAY

While still obscure, the art of Chuka Shaolin has garnered somewhat of a cult following around the world. This has occurred as a result of some international exposure the art received in the early seventies through the book co-written by Cheong Cheng Leong and the late Donn F. Draeger, titled Phoenix-Eye Fist: A Shaolin Fighting Art of South China, and a number of articles that appeared in such magazines as Inside Kung-Fu, Oriental Fighting Arts, and Martial Arts Legends.