Читать книгу Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey - Mark Dery, Mark Dery - Страница 11

Mauve Sunsets

ОглавлениеDugway, 1944–46

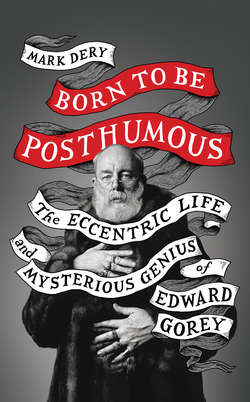

Private Gorey, US Army, circa 1943.

(Elizabeth Morton, private collection)

DUGWAY SITS ABOUT SEVENTY-FIVE miles southwest of Salt Lake City in a no-man’s-land the size of Rhode Island. In the wake of Pearl Harbor, the army had gone looking for a suitably godforsaken patch of land where its Chemical Warfare Service could test chemical, biological, and incendiary weapons. It found it in Dugway Valley, as far from human habitation as any place in the Lower Forty-Eight and cordoned off by mountain ranges, helpful in shielding top-secret experiments from prying eyes.

Dugway Proving Ground was “activated”—officially opened—on March 1, 1942; when Gorey arrived, a little more than two years later, it still had a ramshackle, frontier feel. The high-security areas devoted to top-secret research and testing would’ve been off-limits to Gorey, restricting him to a cluster of buildings about the size of a large city block, maybe two blocks at best.

All around lay wastelands: salt flats, sand dunes, and, from the base to the jagged mountains rearing up to the north and south, the never-ending desert, tufted with saltbush and sagebrush. The stillness was profound, a ringing in the mind. The sky was painfully clear, by day a vaulted blue vastness, at night a black dome powdered with stars.

Not for nothing was the base’s mimeographed newspaper called The Sandblast. “Dust from the local sand dunes, augmented by ancient lake-bed deposits (Lake Bonneville) and volcanic ash beds, pervaded everything each time the wind blew, which was most of the time,” a former Dugwayite recalled.1 New arrivals were greeted with the cheerful salutation, scrawled on the MP gatehouse, “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here,” until top brass caught wind of the offending phrase and ordered it removed.2

Gorey was not enamored of Dugway. “It was a ghastly place, with the desert looming in every direction, so we kept ourselves sloshed on tequila, which wasn’t rationed,” he recalled in 1984. “The only thing the Army did for me was delay my going to college until I was twenty-one, and that I am grateful for.”3 His daily routine, as company clerk—technician fourth grade in the 9770th Technical Service Unit, in armyspeak—didn’t exactly challenge Camp Grant’s all-time high scorer on the army IQ test. He typed military correspondence, sorted mail, and kept the company’s books. “There was this one company: it had all of three people,” he remembered. “One man was in jail, one was in the hospital and one was AWOL for the entire time I was there. But every morning I had to type out this idiot report on the company’s progress.”4

It seems not to have occurred to Gorey, at the time, that swilling tequila and filing absurdist reports was preferable to crawling on your belly through the malarial swamps of some Pacific atoll under withering fire from the Japanese or rotting in a German POW camp. You had hot chow, cold beer—hell, even a bowling alley—and weekend passes to Salt Lake City. Best of all, your chances of dying were next to nil.

Of course, Ted had to grouse. His image, well defined by the time he arrived at Dugway, required that he do his best impression of Algernon Moncrieff from The Importance of Being Earnest, distraught at the impossibility of finding cucumber sandwiches in the middle of the desert. There’s no way of knowing how much of his horror was genuine and how much of it was part of a studied pose.

* * *

Gorey’s time at Dugway wasn’t all lugubrious attitudinizing. Relief arrived in the form of a dark-haired, bespectacled Spokane native named Bill Brandt. A gifted pianist and aspiring composer, Brandt was Dugway’s librarian of classified materials, an assignment that freed him, on weekends, to work on his composing and counterpoint studies. (He would go on to a distinguished career as a professor of music at Washington State University.) “Bill was assigned to the Chemical Warfare Division and Gorey was assigned as company clerk,” Brandt’s wife, Jan, recalled. “Bill had to go to him to order supplies and one day found him reading an avant-garde book. Bill said, ‘Oh! You’re reading one of my favorite books.’ A conversation started and they found they had many interests in common.”5

Five years younger than Brandt, Gorey impressed the older man “as a spare, gawky…boy who played with words,” Jan remembers. Brandt, too, had a quick wit and a knack for wordplay—specifically, puns. Brandt’s own recollection, in an unpublished memoir, of his first encounter with the “new company clerk” portrays Gorey as “a slim, blond man, younger than I, who, I discovered, was literate, in contrast to the professional chemists or old Army types that made up the rest of the outfit. He had actually read the poetry of T. S. Eliot, and Somerset Maugham’s novels!”6

Ted and Bill bonded over their shared interest in Eliot, classical music, and the movies. When Gorey came back from furlough in Chicago with Adolf Busch’s four-record set of Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, he and Brandt commandeered the phonograph in the post library and listened to it “a couple of times late in the evening, when the others in the place had gone.”7

Often, they’d work on creative projects. “I copied music, read, and composed while Gorey wrote the too, too decadent little plays,” remembers Brandt, “or drew the equally decadent Victorians that he later became famous for.” At some point, Gorey painted a illustration for Brandt’s unpublished Quintet for Piano and String Quartet, op. 11 (1943), a whimsical depiction of Harlequin in a piebald body stocking, lounging in a lunar emptiness that suggests Gorey’s idea of Dugway Valley. Overhead, fireworks whizbang against the night sky, a white-on-black fantasia of streaks and curlicues and chrysanthemum bursts. From Harlequin’s rainbow-colored costume to the naïf, Chagall-ish looseness of the rendering, it’s poles apart from the precise, sharp-nibbed aesthetic of Gorey’s little books.

In time, their peas-in-a-pod rapport, artsiness, and manifest lack of interest in barhopping and skirt chasing in Salt Lake City invited the suspicion that Gorey and Brandt were more than good buddies. “Most of the other servicemen thought they were both gay,” says Jan, “but Gorey never put his foot under the bathroom partition,” so to speak. Brandt took Gorey’s sexuality, or what he perceived to be Gorey’s sexuality, in stride: “He was gay, but at that time, naive as I was, I had no idea what that meant and treated him just like anyone else, and his relationship to me was equally straight.”

* * *

At Dugway, Gorey tried his hand at writing, hammering out a full-length play and a handful of one-acts. “The first things that I wrote seriously, for some unknown reason, were plays,” he recalled. “I suppose there must have been some strong dramatic urge at the time. I never tried to get them put on or anything. [T]hey were all very, very exotic and…pretentious, in a way. In another way, I don’t think they were as pretentious as they might have been. I mean, I didn’t go in for endless, dopey, poetic monologues for people; they moved right along. They were rather bizarre, I think, and were rather overwritten…”8 Elsewhere, he added, “I always wonder what I thought I was doing then, because what I was writing was clearly unpresentable—closet dramas, for instance. I had very little sense of purpose, which was just as well, because then I wasn’t disappointed about the outcome.”9

Gorey’s Dugway plays are indeed overwrought. All but one of their titles—typical Gorey kookiness such as Une Lettre des Lutins (a letter from the elves) and Les Serpents de Papier de Soie (the tissue-paper snakes)—are in French, though the plays themselves are in English, with the exception of a five-page effort untranslatably titled Les Scaphandreurs. The dialogue is sprinkled with French phrases, in the manner of Gorey’s correspondence at the time. The characters have names like Piglet Rossetti and Basil Prawn and dress more or less the way you’d imagine people named Piglet Rossetti and Basil Prawn would dress—in purple espadrilles and “mauve satin ribbons [that] cling like bedraggled birds to bosom, thigh, and wrist.”10 They exclaim—there’s a lot of exclaiming—things like “How unutterably mad!” and “How hideously un-chic,” and, of course, “Divine!”11 When they’re not exclaiming, they’re declaiming, in prose so purple it would bring a blush to Walter Pater’s cheek: “Have you ever danced naked before a lesbian sodden with absinthe?”12

Yet despite dialogue so over the top it sounds, at times, like a John Waters remake of The Picture of Dorian Gray, Gorey’s Dugway plays are remarkable if we remember that the author was only nineteen or twenty.13 Too clever by half and too obviously derivative, they’re self-indulgent juvenilia. But the dialogue does move right along: the characters riff off each other, volleying surrealist non sequiturs. A glimmer, at least, of the Gorey we know is recognizable in his first attempts at translating his sensibility onto the page.

The Victorian, Edwardian, and Jazz Age settings he’ll revisit endlessly in his little books are already in place. He’s resurrecting nineteenth-century words long ago fallen into disuse, such as distrait and fantods, words that will become Gorey trademarks. His Anglophilia is in full flower, down to the use of British spellings. The love of nonsensical titles, preposterous names (Centaurea Teep, Mrs. Firedamp), even more preposterous place names (Galloping Fronds, Crumbling Outset), and absurd deaths (suicide by eating live coals, homicide by defenestration from a railway carriage) is amply in evidence. Speaking of names, he’s already indulging his love of pseudonyms: all the plays are penned by “Stephen Crest.”

As well, he’s exploring what will become recurrent themes: the melancholy of lost time (“THE SCENE: An antique room, obscurely decaying”); the stealthy tiptoe of our approaching mortality (symbolized for Gorey by crepuscular or autumnal or wintry light); and, of course, angst, ennui, the banal horrors of everyday life, arbitrary and unpredictable turns of events, cruelty to children (a governess kills her charge’s pet canary), the cruelty of children (a little girl bashes her big sister’s head in with a silver salver), and murder most foul (a woman shoves her friend over a balustrade).14

His instinctive aversion to religion—specifically, Roman Catholicism—makes itself known, too. In Les Aztèques, a character jokes about painting a Crucifixion “with Christ nailed facing the cross instead of with his back to it,” which would have the happy effect of making believers “hideously embarrassed”; in the untranslatably titled L’Aüs et L’Auscultatrice,15 a man is fatally brained by a falling crucifix: an Act of God, played for laughs.

This is a far gothier, more calculatedly outrageous Gorey than we’ll ever meet in his books. He’s clearly in thrall to the Decadent movement associated with Dorian Gray, Baudelaire, and the perverse, pornographic drawings of Aubrey Beardsley. Already he knows that aestheticism, not naturalism, is the stylistic language he’ll speak for the rest of his artistic life.

* * *

Yet in one startling way, the Gorey who speaks to us in the Dugway plays is utterly unlike the Gorey we know from his little books. The plays touch repeatedly on homosexuality and gay culture, and their treatment of these subjects is startlingly frank, given his later reticence on the subject of sexuality—his or anyone’s. While obviously gay characters do have walk-on roles in his little books (and in his freelance illustration work, such as his cartoons for National Lampoon), their sexuality is usually treated lightly, with knowing, deadpan wit. With rare exception, Gorey’s gays are Victorians or Edwardians or Jazz Age sophisticates, at a safe historical remove from the controversies of his historical moment (not to mention his private life).

In the Dugway plays, he takes us inside gay bars, something he never does in his books. There is talk, in Les Aztèques, of “chic dykes” and “violet eyed castrati” and boys dancing with boys, lilacs tucked coquettishly behind their ears.16 In one scene, we’re introduced to a guy who’s “just broken up with some boy” who owns “an enormous mauve teddy bear named Terence,” an image rich in gay symbolism. The teddy bear is borrowed from Evelyn Waugh’s eccentric gay aristocrat Sebastian Flyte, who is never without his beloved childhood companion. And mauve was synonymous in the Victorian mind with aestheticism and gay bohemia, thanks to Wilde’s signature mauve gloves; the association persists to this day in our linkage of lavender with gay culture. Gorey, who by Dugway was already well versed in Victorian literature and culture, was undoubtedly aware of the color’s symbolism. When a character in Les Aztèques observes, “Incredibly mauve sunset,” it’s hard not to imagine that Gorey isn’t sending up the Catholic conservative critic G. K. Chesterton’s famous swipe at the dandified—and, by implication, gay—aesthete who, “if his hair does not match the mauve sunset against which he is standing,…hurriedly dyes his hair another shade of mauve.”17

In the Dugway plays, Gorey is attempting to resolve the fuzzy outline of his creative consciousness—a welter of inspirations and affinities—into a sharply defined artistic voice all his own. At the same time, like everyone crossing the threshold between adolescence and adulthood, he’s struggling toward self-definition as a person, questioning the parental wisdom and societal verities he’s grown up with. Deciding who he wants to be includes coming to terms with his sexuality, however he defines it—or doesn’t.

On the title page of Les Aztèques, Gorey uses an unattributed quotation for an epigraph. Each of us is given a theme all our own at birth, the anonymous author observes. The best we can hope for, in this life, is to “play variations on it.” Fatalistic sentiments for a twenty-year-old. Is he resignedly accepting some aspect of himself he hadn’t fully confronted until that moment, something he thought might be part of a passing phase but has come to realize is innate, irrevocable? On the sheet of A Scene from a Play, we read an even more enigmatic comment, an inscription to Brandt written in Gorey’s flowing script: “For Bill—Because my friendship is inarticulate and indirection is the only alternative.” He signs his inscription with the campy nom de plume he’ll use, at Harvard, in all his letters to Brandt: “Pixie.”

* * *

Gorey was formally discharged from the army on February 2, 1946, at the Separation Center at Fort Douglas, near Salt Lake City. He and Brandt maintained an affectionate, if fitful, correspondence afterward, but it seems to have trailed off after Gorey graduated from Harvard.

In later life, Gorey rarely mentioned his army years. “After more than twenty-five years of knowing him,” says Alexander Theroux in The Strange Case of Edward Gorey, his memoir of his friendship with Gorey, “I had never once heard a single reference, never mind anecdote, of his Army life, or for that matter, of the state of Utah.”18 When the subject did come up in interviews, Gorey inevitably deflected it with a quip about the mysterious incident of the dead sheep, an event straight out of The X-Files.

In March of 1968, upwards of 3,800 sheep grazing in the aptly named Skull Valley, near Dugway, died from unknown causes. Although an internal investigation conceded, in the words of one Dugway commander, “that an open-air test of a lethal chemical agent at Dugway on 13 March 1968 may have contributed to the deaths of the sheep,” the army did not, and does not, accept responsibility for the event, contending that the evidence is inconclusive.19 Whatever the cause, the incident became a flash point for outrage among antiwar activists and environmentalists—and a punch line for Gorey, who found a kind of black humor in the event.

When Dick Cavett asked him, in a 1977 interview, about his time in the army, he said, “Every time I pick up a paper and see, you know, that 12,000 more sheep died mysteriously out in Utah, I think, ‘Oh, they’re at it again.’”20 Still, his memories of Dugway can’t have been all that grim, given his tossed-off remark in a 1947 letter to Brandt: “If you ever get this, slob, write, and let me know what’s been what since we parted at Dugway (do you ever think about the place?—Rosebud [a pet name for a mutual friend at Dugway] and I find ourselves getting sentimental about it every now and then).”21

* * *

Returning to Chicago, Gorey landed an afternoon job at an antiquarian bookshop specializing in railroadiana and a morning job at another bookstore. “I worked in a couple of bookstores, and as a consequence, spent all my salary on books; saw no one at all, and mentally stagnated on the beach on Sundays,” he wrote Brandt. “I did manage to drag myself to hear a lot of chamber music (your influence), usually on stifling hot evenings when one was flooded in one’s own perspiration. However, it all added to the intensity of the experience, or something.”22

In May, Gorey notified Harvard of his intent to register that fall, taking the college up on its long-deferred offer and the scholarship that went with it, supplemented by the GI Bill of Rights. The flood of veterans swelled the class of 1950 to 1,645, the biggest in Harvard’s history; more than half the incoming students were former servicemen, their entrée to one of the nation’s most prestigious Ivies made possible by the GI Bill.

* * *

Asked, on his Veteran Application for Rooms, about his preference in roommates, Gorey said he’d rather share a room with “someone from New England or New York, not any younger than I am, the same religion if possible”—Episcopal, he says, elsewhere on the questionnaire—and “with interests along the lines I have indicated,” namely, art and symphonic music and of course reading (“Mostly French and English moderns, both poetry and fiction”).23

Setting aside his uncharacteristic (and unconvincing) partiality for a fellow Episcopalian—irreligious Ted doing his best to sound like a Harvard man rather than the bohemian weirdo he was?—his response is revealing. His bias in favor of East Coasters invites the perception that he wants to put some distance between himself and the Grant Wood provincialism of the Midwest. He’s embarking on that quintessentially American rite of passage: pulling up stakes and moving far from home, where nobody knows you and you’re free to flaunt your true self or, for that matter, try on new selves.

But if Gorey’s departure for Harvard, at twenty-one, turned the page on his hometown days—he would spend the rest of his life on the East Coast, returning to Chicago for holidays, then infrequently, then hardly ever—the character, culture, and landscape of the city he grew up in left their stamp on him, if you knew where to look. Most obviously, there’s his accent, softened by long years on the East Coast and crossed with the theatrical, ironizing lilt of stereotypical gay speech, but still a dead giveaway. We hear Chicago in Gorey’s elongated vowels, especially in his long, flat a, which sounds like the ea in yeah: in recorded interviews, when he says “back” and “bad” and “happened,” they come out “be-yeah-k” and “be-yeah-d” and “he-yeah-pened.”

More profoundly, there’s his impatience with phoniness and pomposity, a trait native to the industrious, pragmatic city of immigrants he grew up in. Chicago is famously a working-class, beer-and-kielbasa town, staccato in speech, blunt in expression, unpretentious to the point of pugnacity—“perhaps the most typically American place in America,” thought the historian James Bryce.24 Being “regular” is a cardinal virtue.

Of course, Gorey was the least regular guy imaginable, an unapologetic oddity who thought of himself as “a category of one.”25 Still, Larry Osgood, who was in Gorey’s class at Harvard, recalls their classmate George Montgomery saying something about Ted that Osgood “took as really odd at the time, but was really very, very insightful. He said, ‘Ted’s much more normal than the rest of you guys.’” The clique in question was largely gay, and some of its members were, in the parlance of the time, flamboyant in the extreme. “I thought, That’s odd. But there was a level in Ted’s personality, as outrageous as it was, of solid, middle-class values.” Osgood agrees with Freddy English’s characterization of Gorey as “a nice Midwestern boy” in bohemian drag. “The curious thing about Ted in those days, and probably always,” he says, “was that his behavior, tone of voice, gestures, were characteristically queeny, no question about it, but at the core of his personality, he wasn’t a queeny person at all. So except for this bizarre direction he went in in his work, he was a very middle-class, moralistic person.”

Gorey once claimed, with his usual flair for the dramatic, that he was “probably fully formed” by the time he arrived at Harvard.26 No doubt the essential elements of his style and sensibility were intact, many of them already jigsawed into place, but the Ted we know wasn’t quite complete when he walked through the gates of Harvard Yard the week of September 16, 1946.

He would prove a lackadaisical French major, later recalling, “I bounced from the dean’s list to probation and back again.”27 When it came to his extracurricular passions, however, he was an avid student, devouring everything by his latest literary infatuations, going to art films and the ballet, trying his hand at limericks and stories, and drawing constantly (little men in raccoon coats proliferate in the margins of his study notes). For the next four years, he’d be zealous in his true course of study: Becoming Gorey.