Читать книгу Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey - Mark Dery, Mark Dery - Страница 15

Sacred Monsters

ОглавлениеCambridge, 1950–53

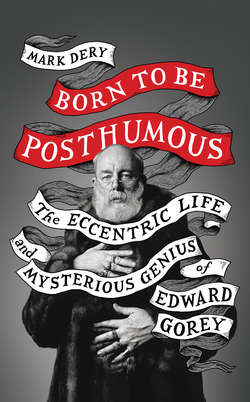

Edward Gorey, poster for “An Entertainment Somewhat in the Victorian Manner” by the Poets’ Theatre. (Larry Osgood, private collection)

THE WAY GOREY TOLD IT, he kicked around Boston two and a half years after Harvard, drifting and dithering in the usual fashion. He was twenty-five and not exactly taking the world by storm.

“I worked for a man who imported British books,” he recalled, “and I worked in various bookstores and starved, more or less, though my family was helping to support me.”1 He entertained vague ideas about pursuing a career in publishing. Or maybe he’d open a bookshop. His pipe dreams vaporized on contact with the unglamorous reality of bookselling. “I wanted to have my own bookstore until I worked in one,” he reflected in 1998. “Then I thought I’d be a librarian until I met some crazy ones.”2 In later, more successful days, he liked to say he was “starving to death” in his Cambridge years, although given his penchant for Dickensian melodrama, who knows if things were quite that dire?3 “I never had to live on peanut butter and bananas, but close,” he claimed in 1978.4

Shortly before graduating, he mentioned, over dinner at the Ciardis’, that he planned to stay in Boston but hadn’t yet found a place. On the spot, John and Judy offered him a room, rent free, in the house they shared with John’s mother in the Boston suburb of Medford. All he had to do in return was feed their cat, Octavius, when they were away that summer.

Installed at the Ciardis’, Gorey pounded the pavement hunting for jobs in publishing, then in advertising, but couldn’t find a berth in either field, he told Bill Brandt in a letter.5 He was writing, desultorily, mostly limericks in his penny-dreadful style. Four years later, he’d collect the best of them in The Listing Attic. According to Alexander Theroux, he “started ‘an endless number of novels,’ now, alas, all jettisoned.”6 “Having nothing to do,” he wrote Brandt, “is the most demoralizing thing known to man.”7 Still, there were always scads of movies he was eager to see and a book, if not “several hundred,” he couldn’t wait to devour.

Jobless and footloose, Gorey started visiting his uncle Ben and aunt Betty Garvey and their daughters, Skee and Eleanor, at their summer house in Barnstable, on the Cape. The Garveys lived in suburban Philadelphia, but Betty, née Elizabeth Hinckley, came from old Cape stock. “Hinckleys have been on the Cape, in one way or another, from the Mayflower,” notes Ken Morton, Skee’s son. The Garveys’ first summer house, near the water on Freezer Road, was the standard beach cottage—“very tiny,” with “ratty cottage furniture,” in Skee’s recollection. It was so overstuffed with Garveys that Ted had to sleep on the porch, which didn’t seem to bother him in the least.

The cramped confines were a goad to get up and go. Gorey and the gang were keen yard-salers and moviegoers and beachcombers and picnickers. “We drove all over the Cape, and you could swim at any beach you happened to arrive at,” Skee remembers. Sometimes they’d take their little motorboat, or a sailboat borrowed from relatives, out to Sandy Neck, an arm of barrier beach embracing Barnstable Harbor. It’s a place of desolate beauty. The shoreline is littered with pebbles, spent ammo in the ocean’s ceaseless bombardment of the land. The dunes are carpeted with bayberry, beach plum, sandwort, and spurge. Some are “walking” dunes, their wind-whipped sands slowly but inexorably engulfing stands of pitch pine and scrub oak. With their clawing branches and bony boughs, these skeletal forests look as if Gorey drew them. Little wonder, then, that he was drawn to them, and kept an eye peeled for fallen limbs beaten by the weather into suggestive shapes—driftwood that “never actually drifted,” Ken calls it.

Shedding his Firbankian persona, Gorey slipped effortlessly into the new role of Cousin Ted, happy to be swept along in the currents of his relatives’ daily routines and social rituals. He was spending his summer days on the Cape “being unlike my usual exotic self,” he told Brandt, “messing about in boats (vide The Wind in the Willows) and having great fun observing Old New England in the person of my aunt’s fantastically typical relatives.”8

The Cape, in the late ’40s and early ’50s, was a world away from Ted’s urbane, killingly witty Harvard clique. Often the Garveys would drop in on Betty’s aunt and uncle, who also spent their summers on the Cape. “They had an open house almost every evening,” says Skee, “with friends and relatives sitting around the living room, talking. It was a lot of gossip and a lot of family stories and he seemed to really enjoy that a lot.” The Garveys and their “fantastically typical relatives” were only the first of a number of loose-knit groups that offered Ted a sense of belonging without the demands—or risks—of emotional intimacy. In years to come, the Balanchinians who orbited around the New York City Ballet, especially Mel and Alex Schierman; Cape Codders such as Rick Jones, Jack Braginton-Smith, Helen Pond, and Herbert Senn; and the actors in his nonsense plays and puppet shows would play that role in Gorey’s life, blurring the line between social circle and surrogate family.

* * *

“I have almost no friends, but the few I do I like very much,” Gorey confided in a January 1951 letter to Brandt.9 Chief among them was Alison Lurie. In later days, she would earn a reputation (and a Pulitzer) as a writer of social satires—sharply observed, subtly feminist comedies of manners, most of them drily amusing in the English way. Barbara Epstein, her Radcliffe schoolmate (and, later, editor of her essays for the New York Review of Books), thought she was “witty, skeptical and articulate” and, even as an undergraduate, a supremely gifted writer.10

But when Lurie met Gorey, she was Alison Bishop, recent Radcliffe grad and newlywed. “After Ted finished Harvard he got a job working for a book publisher in Boston, in Copley Square,” she recalled in 2008. “I was working there, too, at the Boston Public Library, and we used to have lunch together in a cheap cafeteria on Marlborough Street. Neither of us liked our jobs very much, but they had compensations—we got first look at a lot of books, and we could meet regularly.”11 Until Gorey moved to New York, in ’53, she remembered, “we saw more of each other than of anyone else—we were best friends.”

They’d met in ’49, at the Mandrake, she thinks. They clicked instantly, bonding over their shared tastes in literature—“mostly literary classics and the poetry that people were beginning to read then.”12 Naturally, Gorey pressed Firbank and Compton-Burnett on Lurie, who liked Compton-Burnett but “couldn’t stand Firbank; it didn’t seem like literature, it was just posing. [Ted] liked the artificiality, the idea of an imagined world with artificial rules and a kind of old-fashioned overtone.” They went to the ballet and museums and the movies, taking in foreign films and the old movies Gorey was especially fond of. The Gorey Lurie knew was, in all the essentials, the Gorey we know. “Ted then was much like he was always—immensely intelligent, perceptive, amusing, inventive, and skeptical, though he was completely unknown,” she recalled.13 “He saw through anyone who was phony, or pretentious, or out for personal gain, very fast. As he said very early in our friendship,…‘I pity any opportunist who thinks I’m an opportunity.’”

She and Gorey were a matched pair. “We gossiped, we talked about books and movies, I saw his drawings, he looked at what I was writing,” she says.14 “We were both Anglophiles, definitely. [We shared] a love of British literature and poetry and films and all that. We’d both been brought up on British children’s books, so this was a world that was romantic and interesting to us.…Back then, when neither of us had been abroad, it was a kind of fantasy world.”

The Gorey Lurie knew in Cambridge was “strikingly tall and strikingly thin,” a head-turning apparition in his unvarying costume of black turtleneck sweater, chinos, and white sneakers—the standard-issue uniform of that late-’40s hipster, the literary bohemian.15 (By then, he’d shed the long canvas coats with sheepskin collars that he sported at Harvard but hadn’t yet replaced them with the floor-sweeping fur coats of his Victorian beatnik phase. They’d come later, when he moved to Manhattan.)

Gorey “was already eccentric and individual when I first knew him,” said Lurie in 2008.16 One of his distinguishing quirks, she remembers, was that enigmatic combination of sociability and reserve John Ashbery had in mind when he described Gorey as “somehow unable and/or unwilling to engage in a very close friendship with anyone, above a certain good-humored, fun-loving level.” “He had a lot of friends,” she notes, and could be gregarious in the right setting—she recalls him chatting with “a lot of people” who came into the Mandrake—but “was solitary in the sense that he didn’t form a partnership with anybody.”17

Not that there’s anything wrong with that, she says. “Not everybody wants to wake up in the morning and there’s somebody in bed with them, you know? Some people value their solitude, and I think Ted was like that. He wanted to live alone; he wasn’t looking for somebody to be with for the rest of his life. He would have romantic feelings about people, but he wouldn’t really have wanted it to turn into a full-blown relationship, and that’s why it never did.”18 He wasn’t a recluse, she emphasizes, just solitary by nature. “It was important to him to have a place where he could do, and be, by himself.”

Some of Lurie’s most sharply etched memories of Ted are recollections of their rambles in cemeteries, fittingly. In the Old Burying Ground, near Harvard Square, they made rubbings of the “really strange and wonderful” headstones—impressions created by taping a sheet of paper onto a stone, then rubbing it with a crayon.19 Visual echoes of the images they collected—urns and weeping willows from the nineteenth-century tombstones, grinning death’s heads and skull-and-crossbones motifs and “circular patterns that looked like Celtic crosses or magical symbols” from the colonial grave markers—reverberate in Gorey’s books and in the animated title sequence he created for the Masterpiece Theatre spin-off series Mystery! Unsurprisingly, Ted was much taken with “the older tombstones with strange inscriptions and scary verses,” says Lurie. A particular favorite read:

Behold and think as you pass by,

As you are now, so once was I.

As I am now, so you will be.

Prepare to die and follow me.

“It was on one of these trips that I realized for the first time that I was not going to live forever,” Lurie recalled. “Of course I knew this theoretically, but I hadn’t taken it personally. We were in a beautiful graveyard in Concord”—Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, most likely, where Hawthorne, Thoreau, and all the Alcotts sleep on Authors Ridge—“and I said to Ted, ‘If I die, I want to be buried somewhere like this.’ And he said, ‘What do you mean, if you die?’…He was more aware of mortality than I was,” she reflects. “He’d been in the army, and even though he hadn’t been overseas, he’d seen people come back from overseas. Or not come back.”

At the same time, Gorey’s susceptibility to the morose charms of Puritan memento mori had as much to do with his desire to escape the stultifying ’50s, Lurie suggests, as it did any sense that we’ll all end up moldering in the ground. “One of the things you want to remember is what the 1950s were like,” she says. “All of a sudden everybody was sort of square and serious, and the whole idea was that America was this wonderful country and everybody was smiling and eating cornflakes and playing with puppies.” Gorey’s ironic appropriation, in his art, of Puritan gloom and the Victorian cult of death and mourning “was sort of in reaction to this 1950s mystique…that everything was just wonderful and we lived forever and the sun was shining,” she believes.

* * *

That fall, the Ciardis set off for a year in Europe on John’s sabbatical, leaving their “quite huge” apartment to Gorey “for a ridiculously low rental,” he recalled.20 In letters, he played the role he’d perfected by then, equal parts world-weary idler and hopeless flibbertigibbet, buffeted by life’s squalls one minute, becalmed in the doldrums the next. “My life,” he lamented in a letter to Brandt, “is as near not being one as is possible I think. However.”21 There’s a world of meaning in that “however.” It’s the written equivalent of one of Gorey’s melodramatic sighs, signifying something between ennui, weltschmerz, and the shrugging resignation summed up in the Yiddish utterance meh.

Of course, this business about his nearly nonexistent existence was mostly posing. Gorey wasn’t half as indolent as his letters suggested. For example, he illustrated two covers for the Harvard Advocate, the 1950 commencement issue and that fall’s registration issue.22 Credited to “Edward St. J. Gorey,” Ted’s black-and-white for the commencement issue depicts two identical little men standing, in balletic attitudes, on a bleak beach—or is it an ice floe? “L’adieu,” says the caption. His deft use of highly stylized blocks of black against a white background recalls Beardsley’s tour-de-force use of a monochromatic palette as well as the Japanese wood-block prints Gorey loved.

The registration issue made an indelible impression on John Updike, whose Twelve Terrors of Christmas Gorey would one day illustrate. “Gorey came to my attention when I entered Harvard in the fall of 1950,” he remembered in 2003. “The Registration issue of The Harvard Advocate, the college literary magazine, sported a drawn by ‘Edward St. J. Gorey’ that showed, startlingly, two browless, mustachioed, high-collared, seemingly Edwardian gentlemen tossing sticks at two smiling though disembodied jesters’ heads. The style was eccentric but consummately mature; it hardly changed during the next fifty years…”23

Shortly before the Ciardis left for Europe, Dr. Merrill Moore dropped by to confer with John about his forthcoming book of poems. Ciardi moonlighted as editor of the Twayne Library of Modern Poetry, which was slated to bring out Moore’s Illegitimate Sonnets. Moore was a psychiatrist—shrink to the Hollywood director Joshua Logan, the poet Robert Lowell, and about “half of Beacon Hill,” Gorey cracked—and, incongruously, a prolific writer of sonnets.24 During his visit, he happened to see some drawings Ted had given the Ciardis and “was much taken with them,” Gorey told Brandt, “and the upshot, and very frazzling to my already tattered nerves, was that ever since I have been doing drawings for him of an indescribable nature (I do not mean obscene—he has even suggested some semi-o ones, but my Victorian soul shrieked ‘Never!’) at $10 per.”

Gorey’s six cartoons for the endpapers of Illegitimate Sonnets mark his first appearance, in the fall of 1950, in a commercially published book. Meticulously rendered in the style of his most polished work, they depict Gorey’s signature little men acting out single-panel gags that riff on the notion of a sonnet-writing shrink. In “Dr. Merrill Moore Psychoanalyzes the Sonnet,” for example, we see the neurotic Sonnet—personified as one of Gorey’s Earbrass types—on the Freudian couch, free-associating a vision of himself huddled in a bell jar, about to be liberated by a hand brandishing a hammer.

All Gorey had to say about his professional debut as a book illustrator was, “The drawings are neither bad nor excellent, but the reproduction makes them look as if I’d done them with a hang nail on pitted granite.”25 Illegitimate Sonnets marked the beginning of a fruitful, if frazzling, relationship that would see Gorey providing endpaper cartoons for the third printing of Clinical Sonnets (which rolled off the presses in October of 1950, around the same time Illegitimate Sonnets came out); fifty-one drawings of his little men acting out sonnet-related gags plus the front-illustration for Case Record from a Sonnetorium in ’51; and sixty-five illustrations for More Clinical Sonnets in ’53, all of which were published by Twayne.

There’s an unsettling quality to some of Moore’s verse—a darkness behind the drollery. Take More Clinical Sonnets: most of the book’s entries are sardonic portraits of neurotics and depressives; we can’t shake the nasty suspicion that the objects of Moore’s contempt are his own patients. Cartoonish but bleak, Gorey’s drawings accentuate the underlying creepiness of Moore’s blend of jocularity and cruelty.

Still, the exposure could only help Gorey’s nascent career. Moore was well connected in the literary world and, over the course of their four-book collaboration, a tireless drummer for their cause. He even recruited Ed Gorey to target Chicago media. Gorey senior obliged, playing up the hometown-boy-makes-good angle with his PR connections; soon enough, the chitchat columns in Chicago papers started to take notice of Moore’s books—and Ted’s art. By Case Record, he merited a title-page credit: “Cartoons by Edward St. John Gorey.”

“I’m delighted that all goes so well,” Ciardi, on sabbatical, wrote Moore from Rome. “I’m especially delighted that Gorey is getting this chance to launch himself: I have great faith in the final success of his little men. I think they will have to create and educate an audience for themselves, but I see no reason why they shouldn’t…”26

Moore was unquestionably an ardent fan, telling Helen Gorey that he considered Ted “a finer illustrator than Tenniel,” possessed of a rare combination of “satire, social reality, and general artistic integrity,” though the shrink in him couldn’t resist adding, “Much of this has been developed at the expense of a balanced personality…”27 He sang Ted’s praises to prospective publishers, most fortuitously Charles “Cap” Pearce of the New York publishing house Duell, Sloan and Pearce, a bit of matchmaking that secured Gorey a meeting with some of the company’s decision makers to discuss the possibility of a book of his own. (That book, when it came to pass, would be the first title published under his own name, The Unstrung Harp.)

“You were a tremendous success last night,” Moore enthused in a celebratory telegram on December 2, 1951, the day after the meeting.28 “The entire company was captivated by your scrapbook your talents and yourself I am sure something good will come of it Cap Pearce called me this morning to tell me how delighted he was…Good luck you are launched now chum vous sera un succes fou goodbye Arno Cobean and Steig here comes…Gorey.”a

* * *

Even as Ted was making his professional debut in Illegitimate Sonnets, he was being drawn into the creative ferment of the Poets’ Theatre.

In 1950, verse drama was having its moment, and Cambridge was ground zero for American experiments in the form. The trend was fanned by resurgent interest in the verse plays of Stephen Spender, Yeats, Auden, and, most of all, T. S. Eliot. Eliot’s thoughts on the poet as playwright struck a responsive chord in the pre-Beat literary bohemia of early ’50s Cambridge. “Every poet…would like to convey the pleasures of poetry, not only to a larger audience, but to larger groups of people collectively,” he had said in 1933, during a lecture at Harvard, “and the theatre is the best place in which to do it.”29