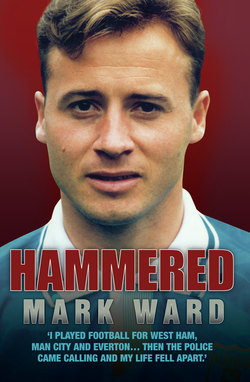

Читать книгу Hammered - I Played Football for West Ham, Man City and Everton… Then the Police Came Calling and My Life Fell Apart - Mark Ward - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1. BORN IN THE ATTIC

ОглавлениеREACHING the top in football became my goal very early in life, so it was perhaps appropriate that I was born in the attic of 25, Belton Road, Huyton, Liverpool on October 10, 1962.

My sister Susan had arrived a year before me. As the eldest of seven children, we became very close as kids. Like all families in the large Ward clan, Mum and Dad kept very busy and seemed to produce a baby almost once a year. Billy turned up just nine months after me, then Tony, followed by Irene, Ann and Andrew. Mum lost a child somewhere in between, so there should really have been eight of us.

In later years I asked Dad why, as his eldest son, I was named Mark William Ward and not Billy, after him. He explained that it was deemed unlucky in our family to name the eldest boy after the father. Apparently, there had been a series of tragic deaths in previous generations of our family, so Dad chose to name his second son Billy instead.

Billy Ward senior came from a large Catholic family of 13 children, with him and Tommy the two youngest. Tommy – who has been a father-figure to me and my brothers since Dad died – tells me that my grandfather had been a stoker in the merchant navy, travelling to Russia in the first world war. My mother, Irene, was one of six kids in a family of Protestants. I’ve got so many cousins and relatives, I’ve never even met half of them.

Dad’s family originated from County Cork in the Republic of Ireland. He used to tell me about his grandmother, Mary McConnell, who came to Liverpool on the boat from Cork. She was blind and he and the other children would have to carry her to the toilet or bathroom.

Ward is a very common name in Ireland. I found out from my Uncle Paddy that they were tinkers – or ‘knackers’ as they were also sometimes called. Many a time on my visits to Ireland as a footballer I’d be asked if I was a knacker. They were not well thought of and were widely regarded as trouble-makers who loved a scrap. That doesn’t sound like me!

Ireland has always been one of my favourite destinations. I love the place and the people who make it so special. I’ve made so many friends in the Emerald Isle and I could happily live there. Dublin is Liverpool without the violence.

I can’t remember much about living in Huyton as a kid, although I do recall my first visit to hospital. I was three or four years old and Mum would allow me to go to the shop at the top of our road – Keyos – that sold just about everything.

I always had a football to dribble to and from the shop. I remember being nearly home, as happy as Larry with my pockets stuffed with sweets, when, all of a sudden, I was hit from behind. It felt like one of the worst tackles I’ve ever experienced. A large Alsatian dog attacked me and caused me to hit the pavement so hard that my head split wide open, with blood gushing everywhere. Luckily, Dad was at home and he picked me up before carrying me all the way to Alder Hey Hospital, where I had the first of many stitches I’d need throughout my life.

I was told the next day that the dog wouldn’t be attacking any more children. Dad had taken his revenge on the beast with a metal pipe.

However, this painful childhood experience did not dampen my desire for sweets. In fact, this mishap effectively became my first-ever coaching lesson. From then on, whenever I went to the shop I’d dribble the ball but with my head up, so that I could see and be aware of everything around me. Instead of looking for my next pass, I was alert to the opposition – the dogs. I’d learned the hard way and didn’t want to go back into hospital again. I wasn’t going to be caught out by any more vicious dogs and there were plenty of them around. Huyton, in the L36 postcode district of Liverpool, was such a tough area, the locals used to reckon that even the dogs would hang around in pairs! In fact, Huyton was also known as ‘Two Dogs Fighting’.

Before he met and married Mum, Dad was a PT instructor in the army and always kept himself extremely fit. Dad was only a small man – 5ft 4ins – but incredibly strong and athletic. At 5ft 6ins, I’m hardly much taller than he was but, more importantly, I inherited his strength and athleticism too. Without those two assets, I could never have made it as a footballer. He would say to me: ‘Strength and speed equals power.’ Although I had to work on my fitness as much as everyone else, I had the capability to reach the levels needed to play at the top level.

As a small child, I remember gazing in admiration at Dad’s trophies on display in the cabinet in our living room. He won medals for football, running, cricket and weightlifting. Signed by Don Welsh, he was a promising left-winger for Liverpool in 1953-54, playing a number of games for the reserves. Uncle Tommy tells me that he once saw a photograph of the entire Liverpool squad lined up on the pitch at Anfield, with his brother stood proudly next to a young lad called Roger Hunt.

But compulsory National Service spoilt Dad’s hopes of becoming a pro. He was shipped out to Hong Kong, where he played for the battalion along with quite a few pro footballers. After completing two years in the army he was demobbed in 1956.

Over the years he’d tell me all about this magical place called Hong Kong. He really enjoyed his time out there and would say: ‘If you ever get the chance, son, visit Hong Kong.’ I would eventually play in Hong Kong for a short period at the end of my career.

* * * *

My parents married at St Columbus Church in Huyton on Grand National Day in April 1960. Dad’s sister, Chrissie, was Mum’s best friend and it was through her that they met.

One special talent I didn’t inherit from Dad was his wonderful left foot. He was actually a two-footed player. If I’d inherited his left peg, I’d have been a far better player – my left foot was hopeless.

As well as making around 10 appearances for Liverpool’s reserve team, Dad also played for South Liverpool, Skelmersdale United and some of the top Sunday League teams in our area, notably the Eagle and Child and the Farmers Arms in Huyton. Comedian Stan Boardman played at centre-forward in the same Farmers Arms team. I’d have a famous fall-out with Stan years later.

Uncle Tommy would take me to watch my father play. Apparently, I was a real handful and would try and run onto the pitch to join in. Although eight years separated them, Tommy was very close to Dad and he, too, was a very good player – as he’s still fond of reminding me to this day! He held the local league scoring record and once netted nine goals in one game, including six with his head.

I’m very close to Tommy and his wife, Helen, who have both always been there for my brothers and I since Dad died in 1988.

Dad taught Tommy how to tie his shoe laces, basic arithmetic and the art of kicking a ball with both feet. He also showed him how to look after himself with his fists, which was a handy skill to have around our way.

Huyton, in the borough of Knowsley, is not only known for being a rough area, though. A number of famous names are also associated with my birthplace. Harold Wilson was the MP for Huyton and the week after my birthday he became Prime Minister. Being a staunch socialist himself, Dad voted for him.

In the second world war, Huyton was home to an internment camp for German and Austrian prisoners of war. Goalkeeper Bert Trautmann was held there before going on to become a Manchester City legend.

Football and Huyton go hand in hand. Over the years there have been many debates among locals as to who would be included in a best-ever Huyton XI. Four definite starters would be Peter Reid, Steven Gerrard, Joey Barton and, of course, myself! What a formidable midfield quartet that would have been.

Reidy played for the Huyton Schoolboys team that won the English Schools Trophy, which was no mean feat. In my fictional Huyton all-time team I can just imagine Reidy commanding the centre of the midfield and pulling the strings with Gerrard powering forward to destroy the opposition, ably supported by the combative Barton and Ward.

Despite my true blue allegiance, I rate Steven Gerrard as the best midfielder I’ve seen in my time – a truly amazing player who has served Liverpool and England with distinction.

* * * *

As the size of our family increased, Mum and Dad decided to move on – to nearby Whiston, which is just a stone’s throw to the east of Huyton, on the other side of the A57. In the summer of 1967 we moved to a bigger, four-bedroom council house at 23 Walpole Avenue. I remember a happy and loving childhood and feeling secure in a very close-knit family. Not that we had much money. Dad was a labourer who found himself in and out of employment, although he always worked hard to provide for us as best he could.

I realised from an early age how relatively poor we were compared to most other kids in our area, and that we weren’t going to get a new bike at Christmas or go on holidays in the summer. We knew better than to ask for things our parents clearly couldn’t afford. I wore the cheapest football boots money could buy and never had a replica Everton kit as a kid. We just didn’t have the money for such luxuries. It didn’t used to bother me much, although it hurt my feelings a bit when I’d go to play for the under-nines and I’d turn up in football boots with holes in them while other kids, who couldn’t even kick a ball properly, were wearing the flashiest boots going.

But I honestly wouldn’t have swapped what we had as a family unit for anything. It was character-building. The most important thing was that there was always food on the table. Although how my parents managed at times I’ll never know.

You had to be smart and fight for everything in our house. If you were last out of bed to get your breakfast, there was a very good chance that there would be no Weetabix or Shredded Wheat left after six hungry kids had devoured it. Even if there were still a few cereal crumbs left at the bottom of the box, the chances were that there would be no milk left to pour on them.

Despite the harsh economics of home life, Mum tried her best to provide a special birthday present for her kids. The only way she could purchase these surprises was by means of the catalogue, paying for items in weekly instalments. On my 10th birthday I received a brand new 12-gear racing bike, which became my pride and joy. I knew that the weekly amount Mum had to re-pay the catalogue company was more than she could really afford but she still made sure I had this special bike to treasure.

I was oblivious to most of the everyday goings-on at home, though, as I fully immersed myself in football. You see few kids doing it today, but playing out in the street was my life. Our house was on the corner and instead of a fence or wall, there were hedges surrounding the garden. They reminded me of the Grand National fences – and they were ideal for smashing a football into. Over the years they got some hammer and the constant daily bombardment from my ball took its toll. While our neighbours’ hedges were all lush and green, ours were bare.

One day I was asked to run an errand for a man called Billy Wilson, who lived opposite. He and his wife May treated me like their own son – I was the spitting image of their grandson Karl who had emigrated to Australia years before I arrived in the street and whom they missed terribly. I had white blond hair just like him, too.

A miner who loved his garden, Billy became a great friend to me and I’d happily run to the shops nearly every day for him to get the Liverpool Echo. He was so generous, he’d give me a threepenny bit almost every time I went to the shops for his Woodbines and papers, which made me well off compared to the other kids in the street.

My first real mate was a lad called Colin Port, who lived in our street and was a couple of years older than me. He became my sparring partner and we competed against each other at everything. Once a week there was always a fall-out between us and it would inevitably end up in a scrap. The truth is that I hated losing at anything – still do – and my attitude to defeat usually sparked a fist-fight.

The first school I attended was Whiston Willis Infants, next door to the junior school. The two playgrounds were adjacent and I’d constantly be caught on the junior school premises playing football with the older lads. Looking back, competing against more senior boys played a massive part in my development as a young player.

After moving up into the juniors, I was picked for the football team two years above my age group, which was unheard of. My first cup final was in 1969 – Whiston Willis Juniors v Bleak Hill at the neutral St Lukes venue. It’s a game that will always remain with me – not for the fact that we won and I scored the equaliser in our 2-1 victory, but because it earned me a pound note. Alan Moss – a lad I still know well – had watched me play from an early age and, before kick-off, he promised to give me a quid if I managed to score.

It seemed like a fortune and when the final whistle blew, as everybody ran on to the pitch and started hugging all the players, I was too busy looking around for ‘Mossy’. He sneaked up behind me, picked me up and placed my first football-related payment in my little hand. My best mate Colin scored the winner to cap a great day.

Alan Moss always had faith that I’d go on to become a pro. Whenever we meet up now, we still talk about the day he paid me a pound for my goal and made the smallest kid on the park feel 10ft tall.

* * * *

My father had his own way of toughening up his eldest son. He would take me with him to visit his brother – my Uncle Joey – two or three times a month. Joey and Aunt Ivy also lived in Huyton but I think Dad took me along more as ‘insurance’. When he left me there to go out drinking with Uncle Joey, he knew he’d have to pick me up at his brother’s place later on and take me back home, which meant he couldn’t stay out all night.

He’d leave me to play with my cousin Kevin Ward, who became the elder brother I never had. Of all my countless cousins, he was the closest to me, even though he was four years older. Kevin had a fearsome reputation around Huyton. No sooner had our fathers sloped off to The Quiet Man or the Eagle and Child for a pint or six then Kevin was lining me up for a fight with one of the local kids – even though these hand-picked opponents were usually older and bigger than me. If they were getting the better of me, as they often did at first, Kevin would come to my aid by giving my rival a slap before sending him on his way.

This went on for years. At first I’d try and hide from Dad when I knew he was planning to visit Uncle Joey’s. He’d always find me, though, and while he never said as much, I’m sure he told Kevin to harden me up a bit. It worked, because I’d gained in confidence when I returned to my hometown of Whiston. I never backed down to any of the local kids and was always in trouble for fighting.

Mr Boardman, the disciplinarian headmaster at Whiston Willis Juniors, had enough of my ongoing battles with a lad called David Maskell, the youngest of six brothers in a family of boxers. One day the Head organised a boxing match between David and myself in the school hall, in front of all the other kids. David knew how to box but I’d never even pulled on a pair of boxing gloves before. I knew I could beat David in a straightforward street fight but the boxing ring was a different matter.

My fears that our bout was going to be one-way traffic proved correct – he boxed my head off. I managed to butt him in the nose and there was blood all over his face but it was so one-sided. When the Head raised David Maskell’s hand to signal his victory at the end of the fight, he barked: ‘I hope this is the end of your fighting.’

Who was he trying to kid? I was so absolutely gutted to have lost to David in the ring that I waited for him after school to exact my revenge – in the street. I just couldn’t let him think that he was better than me at anything. I was never a bully but having this inner drive and sheer will to win became a key part of my make-up from an early age.

My class-mates would ply me with Mars bars, sweets, apples and cans of Coke, just so I’d pick them in my team at play-time. I quickly realised that being good at football made me popular with other kids – including the girls. This continued when I left the Juniors and moved on to Whiston Higher Side Comprehensive school.

* * * *

Life in the Ward household was chaotic at times. Being the eldest lad, it was my job to ensure the younger ones behaved themselves properly when our parents were not around. Our Billy and Irene argued like cat and dog, constantly at each other’s throats over anything and everything.

One day Billy and I were playing darts in our bedroom. The dartboard was hanging from the back of the door but there was a constant distraction in the form of Irene, who was the cheekiest and naughtiest sister you could imagine. She kept running in front of the dartboard to put us off until Billy told her: ‘I’ll throw this dart at you if you don’t go away.’ But Irene being what she was, continued to wind him up all the more.

Before I could say anything, Billy let fly with the dart – and it entered Irene’s head. She had a mass of curly hair and to my horror, the red dart was sticking out of the top of her head. I panicked, knowing I’d get a good hiding if Dad found out. I rushed over to Irene to try and extract the dart but she already had her claws out and was chasing Billy around the bedroom like a raging bull.

As she was about to pounce on my brother, I pulled the dart from her head and got in between them. It was only then that the tears and screams started – not because of the pain caused by the dart, but the fact that she couldn’t get her revenge on Billy!

My brothers and sisters get together occasionally and we reminisce about how violent we were towards each other as kids. Although we’d argue and fight with each other, if any outsiders ever tried to harm any of us, we’d stick together like glue.

* * * *

I was probably about six years old when Dad called me in off the street and told me to run to the bookies for him. If ever he told you to do something, you daren’t refuse or even make him wait.

The nearest betting shop to our house was about half a mile away. Kicking a football in the street had obviously improved my fitness and speed, but running as fast as I could to the betting shop to place Dad’s bet definitely enhanced my aerobic capacity. Many a time I’d been in the middle of a game in the street and be summoned by Dad to go to the bookies as fast as I could because he had a runner at Haydock Park or some other racecourse. Sometimes I’d only have 10 minutes to get there before the ‘off’ and then hope that I wouldn’t have to wait long for a punter to agree to my urgent request to put the bet on.

Regulars in the bookies got to know me as Billy Ward’s lad, so it was never a problem sneaking inside the door. As soon as the bet was placed and I had the receipt slip in my hand, I’d run like the wind to get back and resume playing football in the street. Looking back, I think I ran faster than Dad’s bloody horses – he never gave me a winning ticket to take back to the shop! On the rare occasions that he did back a winner, I think he must have collected his own winnings and then headed straight off to the pub.

The positive from my regular sprints to the bookies was the fact that, from a young age, I learned to run very fast over a fair distance. The downside was that my early introduction to the betting shop and horseracing probably led to my own gambling habit in later years.

I admit, I did develop a big gambling problem in adult life – I’d say after I joined West Ham in 1985. It’s well documented that gambling was, and still is, a footballer’s disease and I’d agree with that because it goes with the territory. Then again, maybe I would still have gambled even if I hadn’t been asked to place Dad’s bets at the bookies.

* * * *

Junior football clubs started to develop around the area where we lived and I was soon signed up to play for a Sunday side called Whiston Cross – later re-named Whiston Juniors – who had, and still have, a big stronghold on all the best young players in the area. Steven Gerrard is their most famous graduate but I also came through the Whiston Juniors system, along with a dozen or so others who went on to make the professional grade, including Karl Connolly (Queens Park Rangers), Ryan McDowell (Manchester City) and John Murphy (Blackpool).

We all owe so much to the managers who looked after the Whiston teams. In my time, without pioneers like Steve Hughes and Brian Lee giving up their spare time to run the clubs, a lot of us wouldn’t have developed into the players we became.

I made more friends from other parts of Whiston and the surrounding areas because football brought us together. Even though we didn’t attend the same schools, we’d hang out together. One of my best mates – and he still is – was a goalkeeper called Kevin Hayes. We nicknamed him ‘The Egg’ because he was brilliant at finding birds’ nests and had a great egg collection. I still call him The Egg to this day.

Peter McGuinness was our left-back with a great left foot. We became close friends and remain so to this day.

Our Whiston Cross team was so successful that we were invited to play at Everton’s Bellefield training ground against the best kids on their books. It proved to be a big turning point in my life. Dad came along to watch but he wasn’t like all the other fathers. He wouldn’t go religiously every week to see me play, whereas some fathers would kick every ball for their boys from the sidelines.

I reckon that Dad knew I had qualities, although he never, ever told me I was good. I’d score four or five goals in a game and dominate the opposition but he’d never tell me afterwards that I’d played well. It was only quite a bit later in my career, when I was at West Ham, that he ever lavished any praise on me. I’ll never forget it. We were sat together in a pub, on one of my home visits, when he suddenly commented I was a far better player than he ever was. I nearly fell off my chair in shock.

Dad didn’t coach me and never told me to do this or that. He just let me develop in my own way. He knew my size would be an obstacle I had to overcome but he also knew I had the qualities of strength and speed that I’d inherited from him.

That game against Everton’s kids was a real lesson. They murdered us 6-0 but – and don’t ask me how – some of our players still came out of the game with credit. Afterwards Everton youth coach Graham Smith approached my father and asked if it would be okay for me to go to Bellefield after school every Tuesday and Thursday night for proper coaching.

Dad agreed and going home that night he told me to just go along and enjoy it. Kevin Hayes – ‘The Egg’ – was also invited back by Everton even though he’d conceded six. It still amazes me how they saw any positive play from me that day, because I hardly kicked the ball – Everton’s kids were that good. But Graham Smith said that it was my never-say-die attitude, even when we were being hopelessly outclassed, and the fact that I kept trying to do the right thing and never hid, that caught his eye.

Dad presumably felt chuffed to see his lad attracting the attention of Everton – the club he’d supported all his life – but if he was, he never showed it.

Training twice a week at Bellefield improved my technique and it was the first time I’d had the benefit of proper coaching. Playing for my school, then Whiston Cross on Sundays and the St Helens Schoolboys district side meant that hardly a day went by without me playing a game. I couldn’t get enough of it.

My mate Colin Port and I would go to Goodison to watch Everton play one week and then see Liverpool at Anfield the next. I was brought up as an Evertonian while Colin was a Rednose.

It was around this time that I was called in to see Ray Minshull, Everton’s youth development officer. I was concerned that I might have done something wrong but he counted out my expenses for travelling to training and they gave me a pair of brand new Adidas boots. They were size six, and a little big for me, but it was a wonderful gesture and made me feel good.

Ray then asked if I’d like to become a ball-boy at Goodison for first team games. Wow! In those days it was every schoolboy’s dream to play for his hometown club and being a ball-boy provided a great opportunity to at least get onto the hallowed turf. The feeling I had while running out with the other nine ball-boys before the opening game of the 1974-75 season was magical. I remember the deafening noise from the crowd, the Z-Cars music and every hair on my body standing up as players such as Bob Latchford, Andy King, Mick Lyons, George Wood and Martin Dobson ran out of the tunnel. It wasn’t the greatest side in Everton’s history but it felt fantastic to be so close to the action and able to take it all in at the age of 11. I realised then, more than ever, that there was nothing I wanted more than to run out with the blue shirt on my back.

Other clubs who showed interest in me included Blackburn Rovers, Manchester United and Liverpool. Jimmy Dewsnip, the local Liverpool scout, invited Dad and I to be Liverpool’s guests at Anfield, where I was dying to meet my idol Kevin Keegan. Even though I was an Evertonian, I loved to watch him play. I can’t remember much about the game itself but I was introduced to Kevin outside the changing rooms afterwards. I was a star-struck 15-year-old as the England star, wearing a vivid red polar neck jumper, shook my hand. The first Cup final I recall watching on telly as a kid was Liverpool’s 3-0 win over Newcastle in 1974, with Keegan scoring twice.

Liverpool were definitely pushing the boat out in an effort to impress. Soon after our visit to Anfield they arranged for me to travel down to Wembley, with a number of other schoolboy players they had their sights on, to watch the 1977 FA Cup final. Liverpool lost 2-1 to Manchester United and the mood on the journey back to Merseyside was very glum, but Bob Paisley’s Reds were destined to lift the European Cup for the first time in Rome just four days later.

Everton got word of my trip to Wembley with their Merseyside rivals and quickly offered me schoolboy forms, much to the annoyance of Jimmy Dewsnip who arrived at our house hoping he’d done enough to convince me to sign for the Reds. The truth is, I was never going to sign for any club other than Everton. I was determined to live my dream and playing for my club would mean everything to me.

Although football dominated my every waking hour, it was around this time that I started to become more aware of my parents’ badly deteriorating relationship. Dad was a proud man and he found it difficult to come to terms with being out of work and unable to provide properly for his family.

He also had a terrible jealous streak where Mum was concerned. It’s so sad, but this was the main cause of their marriage problems.

I couldn’t stop them from breaking up. All I could do was focus all my efforts on becoming a footballer. I lived and breathed the game and my burning desire was to play well enough to earn myself an apprenticeship at the club when I left school at 16. Bill Shankly famously said that football was more important than life or death. That’s how I felt too.